I learn a little about the world from a pilot friend.

I flew my helicopter down to Williams Gateway airport in Chandler yesterday. I need to have some work done on it and that’s where my Robinson mechanic, Kelly, is based. It’s about a 45-minute flight from Wickenburg. Although it’s a lot more pleasant to fly in the morning this time of year, the plan was to work until 3 PM on my Leopard book, fly down there, get picked up by Mike, have dinner in an interesting restaurant, and drive back together.

Company for the Flight

Sometime earlier in the day (just as my office was really heating up with the air conditioning broken), I got the bright idea to see if Alta was home and wanted to come with me for the flight.

Alta had flown with me once before from Chandler Airport, back in the days when I was working on my commercial ticket and was leasing my little R22 back to the flight school. I’d drive down on a Friday and fly for an hour or two with my instructor, then leave my car at the airport and fly the helicopter home. On Monday, I’d fly the helicopter back to Chandler, fly with an instructor for an hour or two, and drive home. Alta accompanied me on one of my flights — I think it was a drive to Chandler/fly to Wickenburg day.

Alta is a flight engineer on 747s. She’s in her early 60s now and works for a charter operation that does mostly freight. Her schedule keeps her out of Wickenburg a lot of the time, which she doesn’t mind very much because, like me, she sees its limitations and needs more out of life. She travels frequently to China and countries that used to be part of the USSR. She occasionally sends postcards of these weird places and I post them on my refrigerator for months on end, wondering what it would be like to actually visit them myself. She’s good company because she’s not only a good listener — which everyone appreciates — but once you get her talking, she’s full of interesting stories.

But because she’s out of town so much, I was very surprised when I called her at home and she answered. I told her what I had in mind and she said she’d be happy to come along.

Delays at Home

The air conditioning guy was supposed to show up at 11:30 AM. He actually showed up at 2:30 PM. In Wickenburg, being 3 hours late is not even considered late. In fact, I considered myself lucky that he came the same day I called. I’m still waiting for the screen guys and I’ve already crossed two landscapers, a builder, a carpet guy, and two painters off my list. (If these can’t return repeated phone calls, they certainly won’t get my business.)

But what was really lucky about the whole thing is that the problem was just a blown capacitor on our 10-year-old heat pump unit. So the entire repair, with service call and diagnostics, was only $150. That compares favorably with the $1,400 we expected to pay for a new unit plus installation.

And today I’ll be comfortable in my office while I work.

Of course the late arrival of the repair guy made me late. I was supposed to stop at a neighbor’s house to try to fix her printer (don’t ask) on my way to the airport. But I didn’t get out of the house until 3:15. So I had to blow that off and expect to apologize profusely about it today. When I got to the airport, Alta was there, waiting for me. I don’t have her cell phone number — I’m not even sure if she has one — so I couldn’t call to tell her I’d be late. (When I called her house, she was already gone.)

The Flight Down

Alta accompanied me to the hanger and kept me company while I preflighted, threw my door in the back, and pulled the helicopter out to the fuel pumps. Alta used to work for me when I had the FBO at Wickenburg Airport. She was one of my best people because she understood what I was trying to do there and had the right attitude about the work. I filled her in on airport gossip as I fueled the helicopter. Then we unhitched it from the towbar, put the cart in the hangar on its charger, and walked back out to the helicopter. It was 3:45 when I finally started the engine.

It was hot. 106°F on the ramp. My door was off, but that didn’t do enough to cool us down. By the time the engine was warmed up — very quickly, I might add — we were both dripping. I made a radio call, picked up, and made a textbook departure down the taxiway parallel to runway 5 with a turnout over the golf course to the southeast

It was a typical late summer afternoon: hazy, hot, and humid. Back in New York, they call that a 3-H day. But in New York, the big H is for humid; in Arizona, it’s for hot. The humidity was only 20-30%, but with surface temperatures in the sun approaching 140°F, it really doesn’t matter how humid it is. Anyone outside will suffer.

With my door off, there was just enough air circulating in the cabin to dry the sweat on our bodies, thus keeping us cool. I’d brought along two bottles of cold water and I sucked mine down. Dehydration is a real issue in Arizona, especially in the summer.

There was enough wind and thermal activity to keep the flight from being smooth. So we bumped along at 700 feet AGL, making a beeline for Camelback Mountain. My usual route is to pass just north of Camelback and east of the Loop 101 freeway, thus threading my way between controlled airspaces so I don’t have to talk to any towers until I get to Williams Gateway.

But as I approached the Metro Center mall on I-17 I thought I’d take Alta down Central Avenue through Phoenix. That meant talking to the tower at Sky Harbor. I dialed in the ATIS, listened to the recording, and then switched to the north tower frequency.

Good radio etiquette requires you to listen before you talk. This prevents you from interrupting an exchange between the tower and another aircraft or, in a UNICOM situation, between two aircraft. I listened. For a full minute. Of silence. I was just starting to think I had the wrong frequency when a Southwest Airlines pilot called the tower. When they were done talking, I identified myself and made my request. The tower cleared me to proceed as requested. I’d go down Central Avenue, then make a left at Baseline. Along the way, I’d cross the extended centerlines for Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport, where the jets were taking off to the west, right over where I’d be flying. (You can read more about flying this route in “Phoenix Sky Harbor to Grand Canyon.”)

As we flew through Phoenix, Alta seemed very interested in landing opportunities. “You can land in just about any of those parks,” she pointed out.

As we flew through Phoenix, Alta seemed very interested in landing opportunities. “You can land in just about any of those parks,” she pointed out.

I knew what she was thinking about. When you train to be a pilot, you’re trained to always think about where you could land in an emergency situation. Phoenix, unlike New York or other older cities, has lots of open space, including parks, vacant lots, and parking lots. There are actually more emergency landing areas in Phoenix than there are in Wickenburg — if you can imagine that.

I wondered briefly what kind of emergency landing zone you’d need to land a 747 in trouble.

All the time, of course, I was descending. I had to be at 1600 feet MSL or lower by the time I got to Thomas Road. By the time we got to the second bunch of tall buildings on Central, we were only about 100 feet off some of the rooftops. I was winding my way between them, about a block west of Central. Then another quick drop in altitude as we crossed the riverbed and I could start to climb a bit again.

I always have trouble remembering which road is Baseline, so I checked street signs as I flew. Phoenix has these very large street signs hanging from traffic signal poles, making it pretty easy to find a street’s name — even from 500 feet above it. I turned left at Baseline and we headed east. A while later, I passed out of the Phoenix surface space. I told the tower I was clear to the east and squawked VFR again.

The final challenge was landing at Williams Gateway. Although I’ve landed there at least a dozen times, I never seem able to manage my approach and landing just the way the tower wants it. They simply are not clear with instructions. To make matters worse, the taxi/ramp area is a bit complex, and doesn’t line up with the runways. So I always fly with an airport diagram handy.

Yesterday, when I called in, the tower asked me if I was familiar. Although admitting it always seems to get me in trouble, I admitted it again: “Zero Mike Lima is familiar.” Now I had to get it right or get yelled at by the tower. Again.

This time, I screwed it up again, but not as bad as usual. Check out the diagram below. The Orange line is what I did last time. Very wrong. I overflew some buildings that I wasn’t supposed to overfly. The Blue line is what I did yesterday. Closer, but not exactly right. After landing, the tower said, “Next time you come in, fly direct to that spot parallel to the runway.” So I think he means I should follow the Green line. I’ll try that next time.

Fortunately, leaving is a lot easier. I just get into position between the runway and ramp on the northwest side of the airport and take off parallel to the runway.

Kelly and his assistant, Kim, came out with ground handling wheels as I shut down. I put the door on the helicopter. They insisted they didn’t need our help dragging it in, so I didn’t argue. I was glazed with sweat. When the helicopter was parked in the hangar, we discussed the work to be done, then left him. It was 5 PM.

Story Time

Mike was waiting in the main terminal, reading a magazine in air conditioned comfort. He told us we looked glazed and we went into the Ladies’ room to splash water on our faces. We then went to dinner. Our first choice, Duals, which was right near the airport, had gone out of business. (It’s a sad state of affairs when people would rather eat in some nationwide chain with the same old menu and factory-prepared food than in a nice, local place.) So we headed over to Ahwatukee and had dinner in an Italian place off I-10. I wish I could remember the name. It’s a nice little place with good food and good service at a reasonable price.

During dinner, Mike quizzed Alta about some of the places she’d flown. Although she’d told me some stories during our flight, she really opened up when questioned. She explained to us that in many places of China and former Soviet Union countries, people were poor to the point of living in ditches and starving. In China, she told me, it’s so bad that people have begun selling their children to brick factories since they can’t afford to feed them anyway. She said that the Chinese people could make do with all kinds of things we’d consider trash — for example, she said, they could make a cart out of two broken bicycle wheels. Sometimes a family of 5 would ride together on a single motorcycle. She said that many people had no knowledge of the things we take for granted.

She told us a story about landing in some former Soviet country — I can’t remember which — that had no security in the cargo area of the airport. When they parked the jet, there were young couples walking hand-in-hand along the ramp area — a cheap date looking at the big planes. She said there were a number of relatively well-dressed young women in the area, collecting planks of wood that had broken off shipping palettes. The flight mechanic told her that these people had nothing at home and were collecting the wood to make benches and other furniture. The mechanic called her down from the flight deck to meet one of these young women and Alta brought her up to the cockpit to see where she worked. Alta said the woman looked very nervous about being there, like she was afraid she’d get in trouble, so Alta cut the visit short and brought her back down to the ramp. She realized later that all of the woman’s friends and acquaintances had seen her go into the plane and that had given her a certain status among them. On their next trip through, she brought Alta a dress as a gift. Alta never got the dress — someone else apparently walked off with it — but she was amazed that this woman, who had nothing, would thank her with such a generous gift.

She also told us a few stories that illustrated the complete lack of quality control in China. She explained that the Chinese people think the point is to make something look good and polished. That’s why they put lead in toy paint — it makes the colors brighter. They sacrifice quality and safety for appearance because they simply don’t understand the importance of quality or safety. That’s not a part of their lives. “If they find a pair of shoes that they can walk in, they’re happy,” Alta explained. “It doesn’t matter if the shoes don’t fit right or fall apart in a month.”

This made me understand the whole Chinese quality problem. It isn’t because they’re trying to make cheap crap. It’s because that’s all they think they have to make. Their standards are so much lower than ours that they think they’re doing a fine job. And because the price is right and Americans have a “disposable good” mentality, we don’t mind buying the same cheap crap over and over. If it breaks, we think, we’ll just throw it away and get a new one. It’s cheap enough. We don’t see the effects on our landfills and in our own economy.

On the drive home, Alta told us about some of her more interesting experiences overseas. Being ignored by airport officials while she was trying to do her job in Dubai because she was a woman. Losing engine on takeoff in Kazakhstan when the aircraft was near max gross weight — 637,000 pounds! Overflying Baghdad, which she does quite often, and being given specially coded transponder codes. Seeing the border of Iraq and Kuwait from 30,000 feet, lit up in bright, white light. Walking down into the cargo hold to check on live cargo like horses and brahma bulls and thousands of baby chicks.

She lives in one world and works in many others. But he time as a world traveler is getting short as she grows older and the newer planes do away with the engineer position. She said it all at one point yesterday: “I’m an antique flying an antique. Does that make me a classic?”

I assured her that it did.

Part two of my commercial airline travel day came when I arrived at the Southwest Airlines gate for my flight. That’s when I remembered why I’d stopped flying Southwest years ago. No assigned seats.

Part two of my commercial airline travel day came when I arrived at the Southwest Airlines gate for my flight. That’s when I remembered why I’d stopped flying Southwest years ago. No assigned seats. Although we taxied right to the runway for departure, when we turned the corner I saw at least a dozen airplanes in line behind us. I guess that’s why the captain was taxiing so quickly on the ramp.

Although we taxied right to the runway for departure, when we turned the corner I saw at least a dozen airplanes in line behind us. I guess that’s why the captain was taxiing so quickly on the ramp.

Then they got their safety briefing and were loaded aboard. I took a photo of them taking off. Then I hiked over to Maverick to meet the Chief Pilot there. I had 45 minutes to kill and planned to make the most of it.

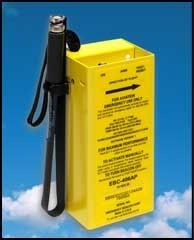

Then they got their safety briefing and were loaded aboard. I took a photo of them taking off. Then I hiked over to Maverick to meet the Chief Pilot there. I had 45 minutes to kill and planned to make the most of it. An ELT is a piece of equipment you hope you never need, but one you pray is working right when you do need it.

An ELT is a piece of equipment you hope you never need, but one you pray is working right when you do need it.