I take (and pass) my Part 135 check ride

I spent most of yesterday with an FAA inspector named Bill. Bill is my POI for Part 135 operations. Frankly, I can’t remember what those letters stand for. But what they mean is that he’s my main man at the FAA in all Part 135 matters.

Yesterday was the second day this week I spent time with Bill. On Wednesday, I’d gone down to Scottsdale (again) to set up my Operating Specifications document on the FAA’s computer system. The FAA has been using this system for years for the airlines and decided to make it mandatory for the smaller operators, including Part 135 operators like me. Rather than put me on the old system and convert me over to the new one, they just set me up on the new one. That’s what we did Wednesday. It took about two hours that morning. Then Bill and I spend another hour reviewing my Statement of Compliance, which still needed a little work, and my MEL, which needed a lot of work.

I had lunch with Paul, my very first flight instructor, and headed back up to Wickenburg, stopping at a mall in a vain attempt to purchase a quality handbag. (Too much junk in stores these days, but I’ll whine about that in another entry.) I stopped at my office and my hangar to pick up a few things, then went home. By 4:00 PM, I was washing Alex the Bird’s cage and my car. (I figured that if I had the hose out for one, I may as well use it on both.) After dinner with Mike, I hit the keyboard to update my Statement of Compliance so it would be ready for Bill in the morning. I added about eight pages in four hours.

A word here about the Statement of Compliance. This required document explains, in detail, how my company, Flying M Air, LLC, will comply with all of the requirements of FARs part 119 and 135. In order to write this, I had to read every single paragraph in each of those parts, make a heading for it, and write up how I’d comply or, if it didn’t apply to my operation, why it didn’t apply. (I wrote “Not applicable: Flying M Air, LLC does not operate multi-engine aircraft” or “Not applicable: Flying M Air, LLC does not provide scheduled service under Part 121” more times than I’d like to count.) Wednesday evening was my third pass at the document. In each revision, I’d been asked to add more detail. So the document kept getting fatter and fatter. Obviously, writing a document like this isn’t a big deal for me — I write for a living. But I could imagine some people really struggling. And it does take time, something that is extremely precious to me.

I was pretty sure my appointment with Bill was for 10:00 AM yesterday. But I figured I’d better be at the hangar at 9:00 AM, just in case I’d gotten that wrong. That wasn’t a big problem, since nervousness about the impending check ride had me up half the night. By 4:00 AM I was ready to climb out of bed and start my day.

Bill’s trip to Wickenburg would include my base inspection as well as my check ride. That means I had to get certain documents required to be at my base of operations, all filed neatly in my hangar. Since none of them were currently there, I had some paperwork to do at the office. I went there first and spent some time photocopying documents and filing the originals in a nice file box I’d bought to store in my new storage closet in the hangar. I used hanging folders with tabs. Very neat and orderly.

I also printed out the Statement of Compliance v3.0 and put it in a binder. I got together copies of my LLC organization documents, too. Those would go to Bill.

I stopped at Screamer’s for a breakfast burrito on the way to the airport. Screamer’s makes the best breakfast burrito I’ve ever had.

I was at the airport by 8:45 AM. I pulled open the hangar door so the sun would come in and warm it up a bit, then stood around, eating my burrito, chatting with Chris as he pulled out his Piper Cub and prepared it for a flight. He taxied away while I began organizing the hangar. By 9:00 AM, I’d pulled Zero-Mike-Lima out onto the ramp. At 9:10 AM, when I was about 1/3 through my preflight, Bill rolled up in his government-issued car.

“I thought you were coming at 10,” I told him.

“I’m always early,” he said. “Well, not always,” he amended after a moment.

Fifty minutes early is very early, at least in my book.

He did the base inspection first. He came into the hangar and I showed him where everything was. But because I didn’t have a desk or table or chairs in there (although I have plenty of room, now that the stagecoach is finally gone), we adjourned to his car to review everything. That required me to make more than a few trips from his car to the hangar to retrieve paperwork, books, and other documents. He was parked pretty close to the hangar door on my side, so getting in and out of his car was a bit of a pain, but not a big deal.

“You need a desk in there,” he said to me.

I told him that I had a desk all ready to be put in there but it was in storage and I needed help getting it out. I told him that my husband was procrastinating about it. I also said that I’d have a better chance at getting the desk out of storage now that an FAA official had told me I needed it. (Of course, when I relayed this to Mike that evening, Mike didn’t believe Bill had said I needed the desk.)

Chris returned with the Cub and tucked it away in Ed’s hangar before Bill could get a look at it. Some people are just FAA-shy. I think Chris is one of them.

Bill and I made a list of the things I still needed to get together. He reviewed my Statement of Compliance, spot-checking a few problem areas. We found one typo and one paragraph that needed changing. He said I could probably finalize it for next week.

My ramp check came next. I asked him if it were true that the FAA could only ramp check commercial operators. (This is something that someone had claimed in a comment to one of my blog entries.) He laughed and said an FAA inspector could ramp check anyone he wanted to. And he proceeded to request all kinds of documents to prove airworthiness. The logbook entry for the last inspection was a sticky point, since the helicopter didn’t really have a last “inspection.” It had been inspected for airworthiness at 5.0 hours. It only had 27.4 hours on its Hobbs. Also, for some reason neither of us knew, the airworthiness certificate had an exception for the hydraulic controls.

Then we took a break so he could make some calls about the airworthiness certificate exemption and log book inspection entry. He spent some time returning phone calls while I finished my preflight.

Next came the check ride, oral part first. We sat in his car while he quizzed me about FAA regulations regarding Part 135 operations, FARs in general, aircraft-specific systems, and helicopter aerodynamics. It went on for about an hour and a half. I knew most of what he asked, although I did have some trouble with time-related items. For example, how many days you have before you have to report an aircraft malfunction (3) and how many days you have before you have to report an aircraft accident (10). I asked him why the FAA didn’t make all the times the same so they’d be easier to remember. He agreed (unofficially, of course) that the differences were stupid, but he said it was because the regulations had been drafted by different people.

That done, we went out to fly. I pulled Zero-Mike-Lima out onto the ramp and removed the ground handling gear. Bill did a thorough walk-around, peaking under the hood. He pointed out that my gearbox oil level looked low. I told him that it had been fine when the helicopter was level by the hangar and that it just looked low because it was cold and because it was parked on a slight slope. Every aircraft has its quirks and I was beginning to learn Zero-Mike-Lima’s.

He asked me to do a safety briefing, just like the one I’d do for my passengers. I did my usual, with two Part 135 items added: location and use of the fire extinguisher and location of the first aid kit. When I tried to demonstrate the door, he said he was familiar with it. “I’m going to show you anyway,” I said. “This is a check ride.” I wasn’t about to get fooled into skipping something I wasn’t supposed to skip.

We climbed in and buckled up. I started it up in two tries — it seems to take a lot of priming on cold mornings — and we settled down to warm it up. Bill started playing with my GPS. The plan had been to fly to Bagdad (a mining town about 50 miles northwest of Wickenburg not to be confused with a Middle East hot spot), but when he realized that neither Wickenburg nor Bagdad had instrument approaches, he decided we should fly to Prescott. I told him that I’d never flown an instrument approach and he assured me it would be easy, especially with the GPS to guide me. So we took off to the north.

It had become a windy day while we were taking care of business in my hangar and the car. The winds on the ground were about 10 to 12 knots and the winds aloft were at least 20 knots. This did not bother me in the least and I have my time at Papillon at the Grand Canyon to thank for that. I’d always been wind-shy — flying that little R22 in windy conditions was too much like piloting a cork on stormy seas. But last spring at the Grand Canyon, flying Bell 206L1s in winds that often gusted to 40 mph or more, turned me into a wind lover. “The wind is your friend,” someone had once told me. And they were right — a good, steady headwind is exactly what you need to get off the ground at high density altitude with a heavy load. But even though gusty and shifting winds could be challenging, when you deal with them enough, flying in them becomes second nature. You come to expect all the little things that could screw you up and this anticipation enables you to react quickly when they do. Frankly, I think flying in an environment like the Grand Canyon should be required for all professional helicopter pilots.

Bill and I chatted a bit about this during part of the flight and he pretty much agreed. But when he told me to deviate around a mountaintop I’d planned to fly right over, I realized that he wasn’t comfortable about the wind. Perhaps he’d spent too much time flying with pilots with less wind experience. Or perhaps he’d had a bit of bad wind experience himself. So we flew south past Peeples Valley and Wilhoit before getting close enough to Prescott to pick up the ATIS at 7000 feet.

Bill made the radio calls, requesting an ILS approach. Prescott tower gave us a squawk code and Bill punched it in for me before I could reach for the buttons. Then Prescott told us to call outbound from Drake. That meant they wanted us on the localizer approach (at least according to Bill; I knew nothing about this stuff since I didn’t have more than the required amount of instrument training to get my commercial ticket). I think Bill realized that they weren’t going to give us vectors — Prescott is a very busy tower — so he punched the localizer approach into the GPS and I turned to the northwest toward the Drake VOR, following the vectors in the GPS. All the time, the GPS mapped our progress on its moving map, which really impressed Bill. At Drake, I turned toward Humpty and Bill called the tower. When they asked how we would terminate the approach, he told them we’d do a low pass over Runway 21L. I just followed the vectors on the GPS toward some unmarked spot in the high desert. We did a procedure turn and started inbound. Five miles out, the tower told us to break off the approach before reaching the runway and turn to a heading of 120. Traffic was using Runway 12, with winds 100 at 15 knots and the tower didn’t want us in the way. So I descended as if I was going to land, then turned to the left just before reaching the wash (which was running). Once we cleared Prescott’s airspace, we headed south, back toward Wickenburg.

We did some hood work over Wagoner. I hate hood work. It makes me sick. I did okay, but not great. Fortunately, I didn’t get sick. But I did need to open the vent a little.

Then we crossed over the Weavers, did a low rotor RPM recovery, and began our search for a confined space landing zone. Personally, I think the spot he picked was way too easy — I routinely land in tougher off-airport locations than that. Then we did an approach to a pinnacle. No problem. On the way back to the airport, we overflew the hospital because he wanted to see LifeNet’s new helipad there. He agreed with me that it was a pretty confined space.

Back at the airport I did an autorotation to a power recovery on Runway 5. It was a non-event. With a 15-knot quartering headwind, only two people on board, and light fuel, Zero-Mike-Lima floated to the ground. I did a hovering autorotation on the taxiway, then hover-taxied back to the ramp with an impressive tailwind and parked.

“Good check ride,” Bill said.

Whew.

After I shut down, we went back to his car, which we were now referring to as his mobile office, and he filled out all the official FAA forms he had to fill out to document that I’d passed the check ride. Then he endorsed my logbook. Then he left. It was 2:30 PM.

I fueled up Zero-Mike-Lima, topping it off in preparation for flying on Saturday, and put it away. I took the rest of the day off. I’d earned it.

Now look at the picture here. In the first two close call incidents, I was the red line, which got clearance to depart to the southeast. In one incident, the blue line (Grand Canyon Helicopters) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In another incident, the green line (AirStar) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In both cases, I had to alert the departing pilots — on the tower frequency — that I was in their departure path. In one case, I actually began evasive maneuvers when the pilot didn’t appear to hear me. Mind you, the tower had given all of us clearance so we were all “cleared” to depart. Scary, no?

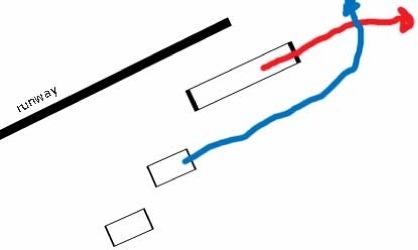

Now look at the picture here. In the first two close call incidents, I was the red line, which got clearance to depart to the southeast. In one incident, the blue line (Grand Canyon Helicopters) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In another incident, the green line (AirStar) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In both cases, I had to alert the departing pilots — on the tower frequency — that I was in their departure path. In one case, I actually began evasive maneuvers when the pilot didn’t appear to hear me. Mind you, the tower had given all of us clearance so we were all “cleared” to depart. Scary, no? Let’s look at another close call. In the picture to the right, I was the red line with a clearance to depart to the northeast. The blue line had just gotten a clearance to depart to the northwest. Because he took off before me, we were on a collision course. But I’d been listening and I heard him get the clearance. So when I took off, I kept an eye out for him and made sure I passed behind him.

Let’s look at another close call. In the picture to the right, I was the red line with a clearance to depart to the northeast. The blue line had just gotten a clearance to depart to the northwest. Because he took off before me, we were on a collision course. But I’d been listening and I heard him get the clearance. So when I took off, I kept an eye out for him and made sure I passed behind him. My most recent controlled close call incident was two days ago. I’d gone down to Chandler to meet a friend for lunch. I landed at the Quantum ramp at Chandler Airport (CHD). We had lunch and returned at close to 1 PM — just when Quantum’s training ships were returning. I asked for and got clearance to hover-taxi to the heliport’s landing pad. I then asked for and got an Alpha departure clearance. This requires me to take off from the helipad and follow a canal that runs beside the airport (and helipad) to the north (the red line). When I got my clearance, the tower alerted me to an inbound helicopter that was crossing over the field. I did not hear that helicopter get a landing clearance, but he may have gotten it from Chandler’s south frequency, which I was not monitoring (because I could not). I took off along the canal just as the other helicopter (the purple line) turned left to follow the canal in. We were definitely on a head-on collision course. I saw this unfolding and diverted to the west, just as the tower said something silly like, “Use caution for landing helicopter.” Duh. I told the tower I was moving out of the way to the west. There was no problem. But I wonder what that student pilot thought. Or what Neil, owner of the company, thought as he hovered near the landing pads in an R44, watching us converge.

My most recent controlled close call incident was two days ago. I’d gone down to Chandler to meet a friend for lunch. I landed at the Quantum ramp at Chandler Airport (CHD). We had lunch and returned at close to 1 PM — just when Quantum’s training ships were returning. I asked for and got clearance to hover-taxi to the heliport’s landing pad. I then asked for and got an Alpha departure clearance. This requires me to take off from the helipad and follow a canal that runs beside the airport (and helipad) to the north (the red line). When I got my clearance, the tower alerted me to an inbound helicopter that was crossing over the field. I did not hear that helicopter get a landing clearance, but he may have gotten it from Chandler’s south frequency, which I was not monitoring (because I could not). I took off along the canal just as the other helicopter (the purple line) turned left to follow the canal in. We were definitely on a head-on collision course. I saw this unfolding and diverted to the west, just as the tower said something silly like, “Use caution for landing helicopter.” Duh. I told the tower I was moving out of the way to the west. There was no problem. But I wonder what that student pilot thought. Or what Neil, owner of the company, thought as he hovered near the landing pads in an R44, watching us converge.