Easier than I expected, but I’m still glad it’s all behind me now.

I picked up my 2005 Robinson R44 Raven II helicopter, Zero-Mike-Lima, from its first 12-year/2200-hour overhaul on Monday, February 20, 2017. I’m very happy with the way it turned out. I thought I’d take a moment to share some information about the process and the way I dealt with it.

About the Overhaul

While most helicopters — most aircraft, actually — have a wide variety of life-limited parts and complex maintenance schedules, Robinson handles maintenance for major components a bit differently. It requires that the entire helicopter be overhauled every 12 years or 2200 hours of flight time, whichever comes first. It does this by syncing the life on certain components so they all need to be inspected, rebuilt, or replaced at the same time.

For example, another helicopter might have blades with a life of 3000 hours and an engine with a life of 2000 hours and a transmission with a life of 1500 hours. The owner/operator/maintenance manager is required to keep track of when each component is due for maintenance or replacement and make sure the helicopter doesn’t overfly the next due item. Then the helicopter needs to be taken offline so that the work that is due can be done. Once it’s finished, that item’s clock is reset (so to speak) and the helicopter continues to operate until the next item needs attention. The benefit to this is that major maintenance costs are spread throughout a helicopter’s life and each maintenance task can be knocked off relatively quickly. The drawback is that there’s a lot of components to track and the helicopter could be down for maintenance quite frequently if it’s flown a lot.

On a Robinson helicopter, the engine, rotor blades, transmission, and other major components are all built to last 12 years or 2200 hours. That’s also when the whole helicopter needs to be thoroughly inspected for frame cracks or other structural problems. So Robinson owners usually get it all done at once as an overhaul.

I say usually because it doesn’t always work out that way. For example, some components — for example, the engine — are limited by hours flown only. So if a helicopter is only a few years old but is flown often, only those components that have a flight time related life limits need to be replaced or inspected. But since you often have to take the helicopter apart to get to those components, it usually makes sense to do the whole overhaul. And there’s always a chance that a helicopter’s component will simply go bad — a blade strike can destroy a set of blades, an engine overspeed can damage an engine, etc. — and that component will be replaced on its own, thus throwing the whole 12-year/2200 hour synced schedule out of whack.

It Ain’t Cheap

An R44 overhaul isn’t cheap. These days it usually runs about $220,000 to $240,000. And no, that isn’t a typo.

But remember this: instead of spending $50K one year for a set of blades and $40K another year for a rebuilt engine and $15K another year for a tail rotor assembly and $15K another year to borescope the frame tubes, you’re paying for everything at once. When it’s done, the helicopter is in like-new condition. (Heck, mine is now worth more than I paid for it 12 years ago.)

I didn’t think much about the overhaul cost during the first few years I owned Zero-Mike-Lima. Ideally, I should have been saving up about $100 for every hour I flew, but I didn’t. I was already paying about $2,100/month on its eight-year loan, about $1,000/month to keep it insured, and anywhere from $3,000 to $8,000 a year on regular maintenance. (Don’t let anyone tell you that owning a helicopter is cheap.) Back in those days, my flying business struggled. I still had this silly idea that I could operate a tour business in (of all places) Wickenburg, AZ, and even when I moved it down to the Deer Valley area for part of the year I couldn’t make a tour business work. So my writing work was funding my flying business and I wasn’t very interested in using my royalties to save up for the helicopter’s overhaul.

But around 2007, things started to change. I discovered the world of aerial survey work and began to understand the value of regular, repeat clients rather than one-time tour passengers. My business began paying its own expenses. Then, in 2008, I got involved in cherry drying work in Washington state and, through careful management of my expenses and the acquisition of new contracts, began making some decent money. (My tenth season is coming up in May and I expect to hire at least five pilots with helicopters to work with me.) It was around 2010 that I was able to start putting aside some of Flying M Air’s revenue for the overhaul. By 2012, I’d saved up $132K, which was pretty darn close to the $150K I should have had saved by then. Not bad, huh?

Of course, it was that $132K and the helicopter that my future wasband and the desperate old whore he moved in with had their eye on in divorce court. But my legal team was smart. We brought in a helicopter flight school owner who operates a fleet of R22 and R44 helicopters as an expert witness. He testified that the money I’d saved was to cover a deferred maintenance expense — which, of course, is what the overhaul is. Fortunately, the judge understood this and I was able to keep the money.

Sadly, a portion of it went to pay for divorce legal fees. But I consider that money well spent since I got to keep the helicopter and a variety of other assets I owned, too. I still don’t understand what made my wasband think he was entitled to any of it. (Expensive delusions?)

Once I’d gotten through the divorce, downsized a bit, and built my new home, I was able to start saving again. Last year’s very rainy cherry season couldn’t have been more timely for me — although I admit I felt bad for my clients. By the time I was ready for the overhaul, I had a bunch of money saved up again.

Timing is Everything

In the first eight years I owned my R44, I flew it almost exactly 200 hours a year. At that rate, it would have needed to go in for overhaul within 11 years.

I thought about overhaul timing starting around 2010 or so. My busy season in Arizona was winter and spring and I wanted the helicopter around for that. And, of course, I needed to take it to Washington for the summer for cherry season, which was starting to really pay off. That meant an autumn overhaul. I’d bring it in around September to get it back by Christmas. That was the plan.

But despite picking up new work doing frost control in California in the late winter/early spring of 2013, I began flying a lot less. My frost and cherry contracts paid to have the helicopter standing by, ready to fly. It didn’t necessarily fly. (This amazes me: that I can fly less and earn more.) When I permanently moved to Washington in May 2013, I no longer had that long ferry flight — at least 10 hours each way — between Arizona and Washington for cherry season. And as I worked to build my new home, I didn’t have as much time for joy flights. So it soon became apparent that the helicopter would go the full 12 years before overhaul.

My season changed, too. Now it was vital to have the helicopter available from late February through September for frost season, cherry season, and local area tours. Winter was absolutely dead — in fact, I’d begun going south for the winter, leaving the helicopter idle in the garage until I needed it in California for frost. Clearly, that would be the best time to get the overhaul done.

I started speaking to overhaul shops about what needed to be done as early as August 2015. They all estimated anywhere from two to four months. That meant dropping it off in October or November 2016 to get it back in time for this year’s frost season.

Researching Overhaul Shops

As you might imagine, you can’t get an overhaul done in just any repair shop. It needs to be an Robinson authorized repair shop. The helicopter is literally stripped down to its frame and rebuilt. I wanted to make sure it was rebuilt by people who knew what they were doing.

I started my search in August 2015, when I brought Zero-Mike-Lima to Hillsboro, OR for an annual inspection. Hillsboro Aviation is the outfit who had sold me the helicopter at Heli Expo in 2004. (I got it priced up there, ordered it two months later, and took delivery six months after that.) They had a good shop full of experienced mechanics that maintained the R22s and R44s for their flight school. But I didn’t get many details then; I wasn’t really thinking about yet.

In November 2015, while I was in Florida visiting my sister, I stopped off to visit a shop in St. Augustine that I knew of. (I had actually rented an R22 from them way back in 2000 or 2001 so I could give my stepdad a ride.) I had no problem with the distance; I figured I could spend some time visiting my sister while they worked on it. They were very receptive and gave me a tour of their hangar, where their mechanics were working on two Robinsons. I was introduced to the guy who would be doing most of the work. “He’s great with Robinsons,” I was told. “He’s been working on them for nine months now.”

Nine months! I thought to myself. I want someone who has been working on them for nine years.

A few months later, in March 2016, I checked out a shop in Salinas, CA. They had a very impressive operation where they did a lot of work on airplanes, including some classics. They could even make their own metal parts using computer-driven fabricators. But they didn’t seem overly eager to do it. It was almost as if they’d take it on as a sort of challenge. And I couldn’t pin them down on timing. Maybe four months, maybe more.

I tried to contact Hillsboro again and, for a while, got no response. Later, I discovered that they’d undergone a personnel change and the guy I’d spoken to was gone. They seemed eager to get the job, though, and I was confident that they’d do it right.

And then I contacted Quantum Helicopters in Chandler, AZ. I had a history with Quantum and it wasn’t all good. I’d gotten my private pilot license with them, finally finishing it up after a year and a half of part-time lessons, taking the summer off to avoid the heat. I liked my instructor a lot and thought the school treated me well. The owner had even been instrumental in helping me buy my first helicopter, a 1999 R22 Beta II. I leased that helicopter back to the school and began my commercial training in it. All was going well until my commercial flight instructor took a job at the Grand Canyon and I just couldn’t seem to do anything to please my new instructor. I was ready to take my check ride but no one would sign me off. I got frustrated and wound up leaving the school. (It took me only 10 days a few months later to finish my training and pass my check ride at a different flight school in Long Beach.) I made the mistake of voicing my concerns and frustration to the owner in a letter and he told me not to bring my helicopter in for maintenance anymore. He later backed down a bit from that position, but it would be ten years before I came back. I was pissed.

Why come back at all? Simply said, Quantum has one of the best Robinson maintenance shops in the country. The Director of Maintenance, Paul, is the same guy who was there in the same job when I started my training back in 1998. That’s 20 years working on Quantum’s Robinsons and before that, he worked at the Robinson factory. He’s got a staff of at least a dozen mechanics and apprentices and they work on Robinson helicopters all day long every day. They know Robinsons. And their maintenance hangar is huge, with enough space to work on at least six helicopters at a time and all the tools they need to fix Robinsons.

When I first came back to them, it was because I had a leak in my hydraulic servos. Another mechanic had told me they’d need to be replaced but hadn’t been able to do it. In a bind, I called Paul and he agreed to take a look. He said that the problem wasn’t uncommon and that there was a good chance the servos would last until overhaul. He told me to keep an eye on it and how much hydraulic fluid needed to be periodically added. He saved me about $2,000 and a week of down time that day. (And he was right; the leak never got worse and the servos lasted until overhaul.)

Before moving to Washington in 2013, I had Quantum do a few of my annual inspections, replace the original fuel tanks with the new bladder tanks, and even install some specialized lighting on the front skid legs. The work was always done right. Best of all, they understood that I wasn’t a sucker with deep pockets. They did what needed to be done to keep the aircraft safe and airworthy and advised me of any potential problems that might need future attention. But they never replaced anything that didn’t need replacing. That saved me a lot of money, too.

So when it came to start getting estimates of overhaul cost, I included Quantum in my list of possible shops to get the job done. Again, it was quite a distance from where I lived in Washington, but I was spending much of my winters in Arizona, anyway.

I also contacted the Robinson factory. They do overhauls, too. In fact, they have a separate assembly line just for overhauls. The benefit of a factory overhaul is that it really does come out just like new. They do everything that could possibly be done to restore it to like-new condition. But I was warned in advance of a few things. First was timing: it could take up to six months. Second was expense: factory overhauls usually cost a lot more than their estimates because any part that is even slightly damaged is replaced — and if it isn’t part of the kit, it’s added to the bill.

The Estimates

The estimates fell into three categories:

- Cheap. The Florida outfit thought that I was mostly concerned with meeting airworthiness requirements as cheaply as possible. They would do the minimum amount of work so I could pay the minimum amount of money. While that may be attractive to some, I’m always skeptical of the lowest bidder. What costs are hidden? Besides, was the nine-month mechanic still there — now with 18 months of experience? Or had he been replaced with a four-month mechanic? I decided I didn’t want to take the chance.

- Reasonable. Quantum’s estimate was reasonable. It was based on the cost of the “overhaul kit” sold by Robinson and just the parts I needed. They’d have my engine rebuilt locally — rather than replace my engine with someone else’s rebuilt engine. (I’m not sure if that matters but I kind of liked the idea.) They had the tools and knowhow to do all the inspections in-house. The factory overhaul estimate, which arrived after I made my decision, was also reasonable, but I already knew that the estimate was misleading; it would cost me 20% to 25% more by the time they finished replacing every single dinged panel with a new one and running it all through the paint shop.

- Expensive or Crazy Expensive. The other estimates were either expensive or crazy expensive. I can’t remember which was which. I’m thinking Salinas was crazy expensive — maybe 20% more than Quantum. The other was close to Quantum’s but I didn’t have the same level of confidence in them as I had with Paul and his team.

So I went with Quantum. And I managed to save about $10K to $12K by not having the helicopter repainted and not replacing the leather seats and headliner, neither of which needed replacement. (I did have the carpet replaced; the pilot side was completely trashed.) After all, I’d taken pretty good care of the helicopter for the past 11+ years and it had spent most of its life in a hangar or garage when not flying. A good detailing and it would look fine.

Paul told me the fastest they’d done an R44 overhaul was about 8 weeks for a very anxious owner. I told him I’d give them 3 and a half months. I’d drop it off in November and pick it up in mid-February. He said that would work for him.

The Last Days before Overhaul

I flew a lot last summer. It was a rainy cherry season and more than a few times I flew all day long, sometimes several days in a row. But I was still at just over 2030 hours at the end of the summer.

With a calendar date set for the overhaul, I began flying as often as possible, hoping to put as many hours on it as I could to get my money’s worth from the overhaul. I took it to an AOPA fly-in near Seattle, then flew it around the Olympic Peninsula and down to visit a friend in Salem, OR. I took almost all of my friends and neighbors for rides, often to my favorite eating spots: Tsillan Cellars winery, Cave B winery, Blustery’s Burger. (Will fly for food.) I went joy flying before or after charter flights.

Then, in early October I took it in for a 50-hour inspection, which includes an oil change. My mechanic found metal in the oil filter. He told me that he’d been seeing some metal for a while, but the amount he now saw was significant. My engine was sending me a message: I’m tired, rebuild me.

On October 18, 2016, Paul wheeled the helicopter into the hangar where the overhaul work would be done.

On October 18, 2016, Paul wheeled the helicopter into the hangar where the overhaul work would be done.

Although it was running smoothly, I decided to move up the calendar a little, mostly to get the helicopter out of my sight so I wouldn’t be tempted to fly it any more. I made arrangements to fly down to Arizona with a friend. Then I did a few last rides that I’d promised to friends and had the oil changed again. I’d decided that if there was a lot of metal in the filter, I’d have it trailered to Arizona. There wasn’t. So I flew, but chose a route that took us near major roads so we could land and get help if the engine started acting up. It didn’t. The flight, which we did over a two-day period in mid-October, went smoothly and, in the evening of October 18, 2016, Paul rolled it into Quantum’s hangar. I would be helicopterless until February.

Down to the Wire

Of course, Paul wasn’t going to start work on my helicopter until I sent money: roughly $171,000. I had money saved up, but not that much. So I needed to get a loan.

I talked to three lenders, including my local bank. In the end, I went with a lender I’d learned about at the AOPA fly-in the previous summer. I filled in all the paperwork online and was approved in 24 hours. It pays to have good credit.

I arranged for two wire transfers: one from the lender and the other from me. They converged at Quantum in the beginning of November, just in time for Paul to order the overhaul kit from Robinson and get it before Robinson closed down for the Christmas holiday. In the meantime, his team began stripping down my helicopter.

Visitation

I made a total of four visits to the helicopter over the next few months.

I arrived in Arizona in early December after a leisurely drive down from Washington with my camper that began the day before Thanksgiving. I was scheduled to dog sit for 10 days for a friend in Wickenburg, but I thought I’d visit the helicopter before I started that gig. So I drove down to Chandler on December 2 for my first look. At this point, they’d been working on it for about a month and it was almost completely disassembled. I blogged about that visit here.

The helicopter’s fuselage was sitting on a rolling wooden cart. You can see more photos here.

Here I am back in December with my brand new tail rotor, still wrapped in foamy paper. That’s my helicopter’s fuselage on the right behind me.

My only regret is that I didn’t bring goodies for the crew that day. I’d gone after a midday trip to the eye doctor and was running late; all I could think about was getting back to Wickenburg before the traffic jams started.

I returned on December 16. I remembered to stop for pizza for the crew that day. The overhaul kit had arrived and I posed for a picture holding the new tail rotor, still in its foam wrapping.

The main rotor blades are a lot longer than the 8-foot bed of my pickup truck.

I returned a few days later, after spending the weekend with some friends in Phoenix. I wasn’t there for the helicopter; I was there to fetch the rotor blades. Robinson doesn’t want old rotor blades out there in the wild, so they require any shop replacing blades to send back the blade roots as proof the blades are not being used elsewhere. (It would be too costly to ship back the whole blades.) Quantum throws away what’s left. But I got this crazy idea that they might look cool hanging in my house. So I went back and fetched them off the recycling pile. I brought them back to Wickenburg in the back of my truck and then later got them hoisted to and tied down on the top of my camper. That’s where they are right now — under my kayak. It’ll be fun getting them down when I get home.

I was busy for the rest of December and most of January and didn’t visit again for a while. I didn’t want to be a nuisance, either. But I did return for one more visit on February 3, 2017. By that time, it was starting to look like my helicopter again, with the tailcone back on and the blades and engine installed. (I think it was the engine that had been holding up progress.)

By February 3, Zero-Mike-Lima was starting to look like my helicopter again.

The main rotor blades, transmission, engine, tail cone, and tail rotor were installed and it would be ready for test flight and blade balancing in a week.

By that point, I’d been communicating with my frost client in California and had an idea of when I needed to be there: February 25. Would the helicopter be done in time? I wanted to pick it up sooner so I could fly it a bit and work out any bugs before I left the state. Paul assured me that he’d begin flying it within a week and that it should be ready soon after that. We agreed on February 20 as a pickup date.

The Pickup

I continued my travels, now with the goal of getting to the Sacramento area with my truck and camper by February 19 so I could hop on a flight to Phoenix on February 20. I spent a few more days in Wickenburg with friends and then hit the road, spending a few days in Death Valley along the way. I had an interesting — read that never again — experience driving through snow storms in mountain passes on the east side of the Sierra Nevada before reaching Lake Tahoe and crossing the mountains on Route 50 at Echo Pass. By the afternoon of February 16, I was at my destination, visiting with friends and making arrangements to park the helicopter and camper for a while.

I also had to make arrangements for one more wire transfer of $48K — the final payoff amount. As I blogged here, I was able to handle that over the phone with the money delivered on Friday since Monday was a holiday.

(If you’re doing the math, the total amount I spent comes out to $219,000 for the overhaul. But that doesn’t count the amount I’ll get back from Robinson for cores sent in for evaluation. Paul seems to think I’ll get about $8K back.)

I arrived at Sky Harbor airport just after noon on February 20. Quantum sent a van to get me. A while later, I was back in the hangar. My helicopter had been moved to where the other R44s and a handful of R66s were parked. It was done.

Zero-Mike-Lima, ready for pickup.

It looked great: clean and almost pristine. But not so pristine that it didn’t look like my helicopter.

I spent about an hour going through the plastic toolbox I’d left behind to store the helicopter’s contents and setting it back up the way I liked it with headsets, iPhone and iPad mounts, extra oil (Paul swapped out the W100 Plus I’d had with some mineral oil I’d need to use for the engine’s first 50 hours), and cleaning supplies. While I worked, I chatted with Paul and the other mechanics as they took care of some last-minute items for me: replacing the cap for the cyclic dual controls, making me a new plastic cover for the pedal area at the front passenger seat, and replacing one of the Danger stickers on the tailcone.

Paul pulls my R44 out of the Quantum hangar after its overhaul on February 20, 2017.

When it was finally set up and Penny, the toolbox, and my luggage was stowed inside, Paul towed it outside onto the ramp. I did a preflight and added a quart of oil. And then I got in and started it up.

It might sound weird but when you’ve flown the same aircraft — and only that aircraft — for 12 years and over 2,000 hours, you really get to know the way it sounds and feels. The fuel pump sounded different. The startup process felt different. The engine sounded different. And when the blades started spinning, I heard a definite whistle that hadn’t been there before.

I called Paul from the cockpit, using my Bluetooth-enabled Bose headset. “The blades make a whistling noise now,” I said. He was standing on the ramp just outside the hangar watching me. He told me they will sound different because the new blades are stiffer than the old ones. I wasn’t too happy about that but I was very happy to have the new blades, which I knew were a lot better than the originals. The old ones were barely within specs for airworthiness and I was thrilled that they’d made it to overhaul.

When I took off, it just about jumped into the sky. I’d later discover that it cruised about 10 knots faster than it used to. Nothing like a rebuilt engine.

I flew it to visit friends at Falcon Field in Mesa and then took two of them for a flight up the Salt River as far as Roosevelt Lake. The next day, I went to Wickenburg and then took two friends for an overnight trip to Bisbee (their choice). I noticed that the cylinder head temperature was running higher than it used to and it was burning a lot of oil. I texted Paul about it. He said it was the mineral oil and that it should cool down once the rings set. I sent more pizza.

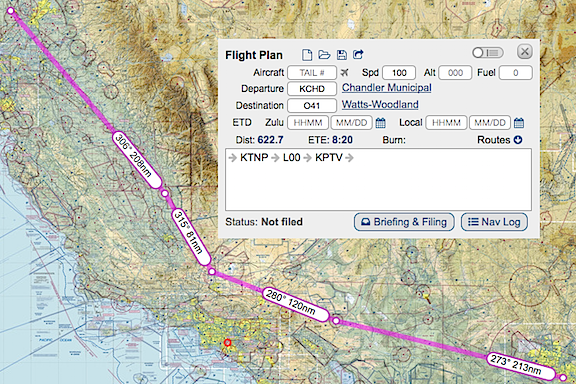

I took three other friends to Sedona for breakfast and it performed magnificently at altitude on a relatively warm day. Then I flew back down to Chandler to have a few minor things tended to: clutch belt adjustment, strobe light fix, and oil change. The next day, I flew it to California with a friend.

Postscript

Zero-Mike-Lima was parked on the ramp at Woodland for a few days. I took it for a little joy flight out over Lake Berryessa (which is full) to see the “Glory Hole” and came back to the airport via Cache Creek. Then I decided that I wanted it in a secure, sheltered place so I made arrangements to hangar it with a friend’s helicopter at another airport nearby. Yesterday I took it to Sacramento Mather airport to have the battery in the Garmin 420 panel mounted GPS changed. And I took it for another flight to make sure the traffic feature of the Mode S transponder still works with the GPS.

On Sunday or Monday, I’ll start my drive home with my truck and camper. Today’s weather is kind of dreary, but I’ll be sure to take Zero-Mike-Lima out at least one more time before I head home. Unless I get called out for frost protection, it’ll be a long time before I get a chance to fly it again.

Meanwhile, I’m glad to have the overhaul behind me. Finding the right shop, arranging for payment, and then waiting for it to be finished were somewhat stressful tasks that had to be done. Now I’ve got a helicopter with a clean bill of health and few maintenance items ahead of me for the next few years. I suspect my cost of operations will drop, helping my business stay more profitable in the years to come.

And yes, this is likely my last overhaul. I figure I’ll retire from flying in about ten years, which should be before the next overhaul is due. The next owner is likely to get quite a deal on a well-kept machine — and possibly my business at the same time. Stay tuned.

Congratulations! You’ve made it to the end of yet another lengthy blog post here on

An Eclectic Mind. If you got this far, you must have gotten

something out of what you read. And isn’t it nice to read Web content that isn’t full of annoying ads?

How about doing something to show your appreciation? I’d love it if you’d add a comment at the end of this post to share your feedback with me and others. But I’d really love it if you’d visit my Support page and chip in a few dollars to help cover the cost of hosting this blog and motivate me to keep writing new, interesting content. It’ll only take a moment and I really would appreciate it!

On October 18, 2016, Paul wheeled the helicopter into the hangar where the overhaul work would be done.

On October 18, 2016, Paul wheeled the helicopter into the hangar where the overhaul work would be done.