Wickenburg to Page, AZ.

– Day 1: Wickenburg to Page, AZ

– Day 2: Page, AZ to Bryce Canyon, UT

– Day 3 AM: Bryce Canyon to Salt Lake City, UT

Regular readers of this blog who don’t follow me on Twitter might have been wondering where I’ve been. Did I fall off the face of the earth? Or finally, after six years, get tired of blogging?

Neither. I was making my annual helicopter repositioning flight to Washington State.

This year, I got an early start, piggy-backing my long cross-country flight at the end of a photo flight at Lake Powell. A photographer was willing to pay for the 4-hour round trip ferry time for me to get the helicopter from the Phoenix area to Page, AZ. At the end of that flight, I continued north to Salt Lake City instead of heading home. This put me several hours closer to my destination. At Salt Lake City, I picked up Jason, a low-time CFII interested in building R44 time for much less than the cost of renting. With Jason at the controls, we continued to Seattle.

The trip can easily be summarized by the number of days it took to complete. I’m putting it all down here, in four parts, while it’s still fresh in my mind. The photos aren’t terribly good due to glare through the bubble, but I hope the illustrate some of the terrain and weather we encountered.

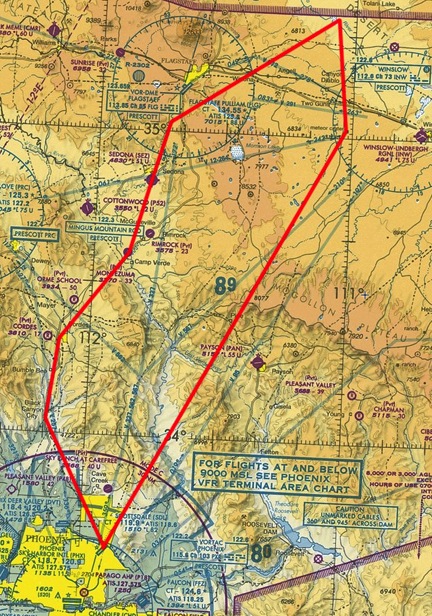

In this first part, I’ll cover my trip from Wickenburg to Page, AZ. You can click here to see my approximate route on SkyVector.com.

I’ve made the trip from Wickenburg to Page (or Page to Wickenburg) countless times. It’s the kind of trip that I don’t even need to consult a chart to complete. I know the landmarks by heart.

But on Thursday, the weather promised to be a factor. Although it was sunny down in Wickenburg as I preflighted around 2:30 PM, the clouds were building to the north. I could see them thickening over the Weaver Mountains 15 miles away. And all the forecasts for all the points north of the Weavers called for high winds gusting into the 30s. It would be a bumpy ride.

So bumpy, in fact, that my friend Don and his wife decided not to join me on my trip to Page. Don’s got a helicopter very much like mine and he’d planned to fly up there with me, spend two nights, and let me show him around Lake Powell between my photo flights. But with the forecast so nasty, he bowed out. I didn’t blame him. No one wants to spend 2 hours getting thrown around the sky in a relatively tiny bubble of metal, Fiberglas, and Plexiglas.

And if wind wasn’t enough of a deterrent, the forecast also called for isolated showers and thundershowers north of I-40. So I knew I’d be dodging weather, too.

But I had a contract and my client had paid me to fly up there. I had a pilot waiting for me in Salt Lake City for a Saturday departure. The weather would have to be impossible to fly through to prevent me from making the flight.

So at 3:30 PM, I took off from Wickenburg (E25) into a 15 mph wind from the west and turned out to the north.

I climbed steadily at about 200-300 feet per minute, gaining altitude slowly to clear the 5,000 foot Weaver Mountains ahead of me. Below me, I could see the scars the near-bankrupt developers had left on the desert where Routes 93 and 89 split off. Greed had scraped the desert clean, built a golf course, and then let the grass wither and die. Where there was once pristine rolling hills studded with cacti and small desert trees, there was now flattened dirt, void of vegetation, shaped by bulldozers and men. A dust bowl on windy days covering hundreds of acres of Sonoran desert.

I climbed steadily at about 200-300 feet per minute, gaining altitude slowly to clear the 5,000 foot Weaver Mountains ahead of me. Below me, I could see the scars the near-bankrupt developers had left on the desert where Routes 93 and 89 split off. Greed had scraped the desert clean, built a golf course, and then let the grass wither and die. Where there was once pristine rolling hills studded with cacti and small desert trees, there was now flattened dirt, void of vegetation, shaped by bulldozers and men. A dust bowl on windy days covering hundreds of acres of Sonoran desert.

I continued to climb, looking out at the Weaver Mountains ahead of me. The clouds were low over the mountain tops and I could clearly see patches of rain falling. The wind was moving the weather along at a remarkable pace. I picked a spot to cross the mountains, preferring the place where Route 89 climbs into Yarnell over the more direct crossing at the ghost town of Stanton and the valley beyond it. I knew from experience that the wind would be setting up some wicked turbulence in that valley as it gusted over Rich Hill and Antelope Peak. I braced for the turbulence I expected as I topped the hill at 5,000 feet MSL and was surprised when I wasn’t blasted.

That’s not to say there wasn’t turbulence. There was. But it was the annoying kind that bounces you around every once in a while just for the hell of it. The kind that makes flying unpleasant but not intolerable. The kind pilots just deal with.

Ahead of me was Peeples Valley, which was remarkably green. Our winter and spring rains had fallen as snow up there and it wasn’t until the warm weather began arriving that the grass could start sucking it up. The result was a carpet of new green grass that made good eating for the open range cattle and horses up there. All it needed was a little sun to give the illusion of irrigated pasture. But the sun was spotty, coming through breaks in low-hanging cumulous clouds.

The weather up ahead gave me a good idea of what I’d be facing for much of the trip: a never-ending series of isolated rain and snow showers. They appeared as low clouds with hanging tendrils of wispy precipitation. But unlike the gray rains hanging below summer rainclouds, these were white, making me wonder whether I was looking at rain or snow. With outside air temperature around 4°C (40°F), it could have been either. Or something worse; damaging hail or icy sleet.

The weather up ahead gave me a good idea of what I’d be facing for much of the trip: a never-ending series of isolated rain and snow showers. They appeared as low clouds with hanging tendrils of wispy precipitation. But unlike the gray rains hanging below summer rainclouds, these were white, making me wonder whether I was looking at rain or snow. With outside air temperature around 4°C (40°F), it could have been either. Or something worse; damaging hail or icy sleet.

I’d been taught at the Grand Canyon that if you can see through it, you can fly through it. But I didn’t think that rule applied to late spring storms at high elevations. I wasn’t going to fly through anything I didn’t have to.

Knowing which way the storms were moving made it easy to skirt around their back sides. Up near Kirkland, this put me several more miles west of my intended course. Before taking off, I’d punched the waypoint to our property at Howard Mesa into my GPS; I always fly over anytime I’m close, just to make sure everything is okay. Having flown the route dozens of times, I should be flying much closer to Granite Mountain. But that mountain was completely socked in by one of the storms, so I passed to the west of it, adjusted my course line with the push of two buttons, and continued northeast.

Near the Drake VOR, I detoured more to the east to avoid a rapidly approaching shower. Raindrops fell on my cockpit bubble and the 110 wind of my airspeed whisked them away. The sky was clearer ahead of me, although the tops of Bill Williams Mountain was still shrouded in clouds. The Prescott (KPRC) ATIS reported mountain obscuration and snow showers to the north, east, and west. I couldn’t see the San Francisco Peaks, which were likely getting more snow to extend the skiing season at the Snow Bowl.

Near the Drake VOR, I detoured more to the east to avoid a rapidly approaching shower. Raindrops fell on my cockpit bubble and the 110 wind of my airspeed whisked them away. The sky was clearer ahead of me, although the tops of Bill Williams Mountain was still shrouded in clouds. The Prescott (KPRC) ATIS reported mountain obscuration and snow showers to the north, east, and west. I couldn’t see the San Francisco Peaks, which were likely getting more snow to extend the skiing season at the Snow Bowl.

Then I was back out in the sun — a good thing, since the outside temperature had dropped to just over freezing and my cabin heat wasn’t able to keep up with the cold. I climbed up the Mongollon Rim just west of Bill Williams Mountain, trading high desert scrub for ponderosa pines. The mountain had recently been dusted with fresh snow. That didn’t surprise me; only three hours before, the airport at Williams (KCMR) had been reporting 1/4 mile visibility.

Then I was back out in the sun — a good thing, since the outside temperature had dropped to just over freezing and my cabin heat wasn’t able to keep up with the cold. I climbed up the Mongollon Rim just west of Bill Williams Mountain, trading high desert scrub for ponderosa pines. The mountain had recently been dusted with fresh snow. That didn’t surprise me; only three hours before, the airport at Williams (KCMR) had been reporting 1/4 mile visibility.

By now, the turbulence had become a minor nuisance that didn’t bother me much. I was listening to a genius mix on my iPod, hearing songs I didn’t even know I owned and trying to enjoy the flight. I was almost an hour into it and had more than an hour to go.

I reached Howard Mesa and flew over our place. Everything looked fine. I was surprised to see the wind sock hanging almost limp. Surely there was more wind than that.

I punched the next waypoint into my GPS; a point on the far east end of Grand Canyon’s restricted airspace. I wasn’t allowed to overfly the Grand Canyon below 10,500 feet. Since my helicopter starts rattling like a jalopy on a dirt road over 9,500 feet, that was not an option. Besides, one look out in that direction told me that no one would be flying anywhere near the Grand Canyon that day. All I could see to the north was a blanket of low clouds. I couldn’t even see Red Butte, a distinct rock formation that can normally be seen from 50 miles away. The Grand Canyon (KGCN) ATIS confirmed that things were iffy. The recording reported “rapidly changing conditions” and instructed pilots to call the tower for current conditions. You don’t hear that too often on an ATIS recording.

My course would take me east of that area, but the weather was also moving east. It soon became apparent that I was in a race against the storm. I was halfway to my waypoint when I realized that I wasn’t going to be able to go that way. Although there was a gap there between two storms, I knew from experience that gaps can disappear quickly, swallowing up whatever naive pilot slipped inside. The temperature had dropped down to 0°C and the clouds were only 300 feet above me as I zipped across the high desert, 500 feet off the ground. I’d have to detour to the east.

I aimed for the leading edge of the storm, hoping I could reach it and go around it. But the leading edge was racing eastward to cut me off. My course kept drifting eastward until I was heading due east. That would put me, eventually, over the Navajo and Hopi Reservations, far from any major road or town. I didn’t want to go that way.

I came down off the Coconino Plateau just southwest of Cameron. At least that’s where I figured I was. The low-hanging clouds had blocked all of my normal landmarks from view. To the north, where I needed to go, was a solid sheet of gray rainfall, blocking out whatever lay beyond it. As I descended from the plateau, still heading east, I began thinking of making a precautionary landing and waiting out the storm.

Then I saw a break in the storm with bright sunlight beyond it. It was still raining there, but I could clearly see my way through and what I saw looked pretty good. I banked to the north and entered the rainstorm. Soon, I was being pelted by rain. Visibility was still tolerable; I could see well enough to fly. Thankfully, there were no downdrafts to contend with. Just turbulence, rocking me around, punishing me for interfering with nature’s gift of rain. I held on and rode it out.

And that’s when the carbon monoxide detector light went on. On departure, I thought the heat had smelled a little more like engine exhaust than usual, but had put it out of my mind. The warning light brought it right to the front of my mind again. I opened my door vent and the main vent and pushed the heater control to the off position. I took stock of the way I felt: any symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning? No, I felt fine. But soon I’d feel very cold.

I passed through the rain and emerged on the other side with a clean cockpit bubble and likely very clean rotor blades. Ahead of me, now due north again, the sky was brighter and I could clearly see the Echo Cliffs. Before entering the storm, I’d punched Tuba City (T03) into my GPS to keep my bearings; now I punched in Page (KPGA) and was pleased to see that I was already right on course. I aimed for The Gap, a small town at the gap in the cliffs, right on Route 89, adjusted power to maximize speed, and sped forward, 500 feet off the high desert floor.

I passed through the rain and emerged on the other side with a clean cockpit bubble and likely very clean rotor blades. Ahead of me, now due north again, the sky was brighter and I could clearly see the Echo Cliffs. Before entering the storm, I’d punched Tuba City (T03) into my GPS to keep my bearings; now I punched in Page (KPGA) and was pleased to see that I was already right on course. I aimed for The Gap, a small town at the gap in the cliffs, right on Route 89, adjusted power to maximize speed, and sped forward, 500 feet off the high desert floor.

The rest of the trip isn’t very interesting. I did get some different views to the west, where the Grand Canyon was still covered by a thick blanket of clouds. It would be snowing there, especially over the North Rim. My usual path was at least 20 miles to the west, much closer to the Canyon. It included overflying the Little Colorado River Gorge and mile after mile of nearly deserted flatlands on the far west edge of the Navajo Indian Reservation. I was still over the reservation on this path, but the land below me was sculpted by wind and water into mildly interesting patterns. This was the western edge of the Painted Desert, which is not quite as picturesque as most people think.

I crossed Highway 89 at The Gap and flew through the gap in the Echo Cliffs. I was now about 45 miles from Page, flying among three sets of high tension power lines that stretched from the Navajo Generating Station on Lake Powell to points south. There was a dirt road here that made a short cut to page — if you didn’t mind driving more than 40 miles on a dirt road. Navajo homesteads were scattered about. The sky was a mixture of clouds and patches of deep blue. I warmed in the sunny spots and cooled in the shadows.

I crossed Highway 89 at The Gap and flew through the gap in the Echo Cliffs. I was now about 45 miles from Page, flying among three sets of high tension power lines that stretched from the Navajo Generating Station on Lake Powell to points south. There was a dirt road here that made a short cut to page — if you didn’t mind driving more than 40 miles on a dirt road. Navajo homesteads were scattered about. The sky was a mixture of clouds and patches of deep blue. I warmed in the sunny spots and cooled in the shadows.

It was after 5 PM and I was starting to worry about reaching Page in time to pick up my rental car at 5:30. I began making calls to the FBO from 25 miles out. No answer. A while later, another plane called in from the northwest. Other than that, silence.

I was fifteen miles out when Lake Powell came into view. It looked gray and angry under mostly cloudy skies.

I landed on the taxiway parallel to runway 33 and went right to parking. A line guy from American Aviation arrived with a golf cart to pick me up. I shut down and jumped in. It was 5:30 PM; the 200 NM flight had taken almost exactly 2 hours. I was just in time to get my rental car.