It’s all about a difference in goals.

I think a lot about the goal differences between helicopter owners and pilots. This could be because of my annual involvement in cherry drying work which is one of the few kinds of work that probably appeal more to owners than pilots.

What Owners Want

I think I can safely say that all owners–whether they own and fly for pleasure or own primarily as part of their business–want to keep owning the helicopter. That means keeping costs low and revenue–if any–as high as possible without jacking up costs so they can continue to meet the financial obligations of ownership: insurance, debt service, storage, required maintenance, registration, taxes, etc.

Of course, if a helicopter is owned as part of a business, the owner’s main goal is probably to build that bottom line. That means maximizing revenue while minimizing expenses. While every helicopter has some fixed costs that come into play whether it flies or not–insurance, hangaring, annual maintenance–an owner can minimize costs by focusing on work that pays even if the helicopter doesn’t fly. That’s why you can lease a helicopter with a monthly lease fee that’s independent of hours flown and why certain types of agricultural work–cherry drying and frost control come to mind–pay a standby fee that guarantees revenue even if the helicopter is idle.

As an owner, I can assure you that there’s nothing sweeter than having your helicopter bring in hundreds or even thousands of dollars a day while it’s safely parked at a secure airport or, better yet, in a hangar.

If the helicopter does have to fly, the owner wants the highest rate he can get for every flight hour and the lowest operating cost. How he achieves those goals depends on his business model, the equipment he has, the services he offers, and the pilots who do the flying.

What Pilots Want

What pilots want varies depending on where they are in their career.

- Student pilots want to learn. Their goal is to learn what they need to and practice it enough so they can take and pass checkrides. Because they’re paying full price for every hour they fly, they’re not necessarily interested in flying unless it enables them to practice the maneuvers they need to get right on a check ride.

- New pilots want to fly. Period. Their primary interest is building the time they need to get their first “real” flying job: normally 1,000 to 1,500 hours PIC. They’ll do any flying that’s available. And even though commercial pilots and CFI may be able to get paid to fly, some will fly for free or even pay to fly if the price is right. Indeed, I’ve had more than a few pilots offer to fly for me for free, which makes me sad.

- Semi-experienced pilots want to build skills. Pilots who have had a job or two and have built 2,000 hours or more of flight time are (or should be) interested in doing the kind of flying that will build new skills or get practice in the skills they want to focus on for their careers. So although they still want to fly, they’re more picky about the flying they do. They’ll choose a job with a tour company that also does utility work over a job with a tour company that doesn’t, for example, if they’re interested in learning long-line skills.

- Experienced pilots want flying jobs doing the kind of work they like to do and/or paying the money they want to receive for their services. Pilots with a good amount of experience and specialized sills are often a lot pickier about the jobs they take. For some of these pilots, flying isn’t nearly as important as pay and lifestyle. A utility pilot friend of mine routinely turned down jobs if he didn’t like the schedule, just because he didn’t like being away from home more than 10 days at a time. But dangle a signing bonus in front of him and there was a good chance he’d take it.

Of course, there are exceptions to all of these generalizations. Few people fall neatly into any one category.

But what you may notice is that most of them need to fly to achieve their goals, whether it’s passing check rides, building time, learning skills, or bringing home a good paycheck.

And that’s how they differ from owners.

Owner Pilots

I’m fortunate–or unfortunate, if you look at my helicopter-related bills–to be both an owner and a pilot. I’ve owned a helicopter nearly as long as I’ve been flying: 15 years.

The owner side of me is all about the revenue. I love agricultural contracts that let me park the helicopter on standby and collect a daily fee for leaving it idle. Every hour it doesn’t fly is another flight hour I can keep it before I have to pay that big overhaul bill. (I own a Robinson R44 Raven II, which requires an overhaul at 12 years or 2200 hours of flight time, whichever comes first.) It’s also an hour I don’t have to worry about a mishap doing the somewhat dangerous agricultural flying work I do.

The pilot side of me wants to fly. I love to fly. I bought a helicopter because I felt addicted to flying and needed to be able to get a fix any time. (The business came later, when it had to.)

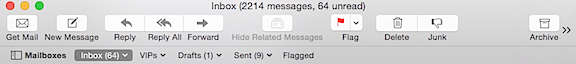

Owning a helicopter means having a safe place to keep it when it’s not flying.

And because I’m an owner, with ultimate say over how the helicopter is used, and a pilot, with a real desire to fly, I can pretty much fly where and when I want to. But when the fun is over I’m the one who has to pay the bill.

Being an owner pilot gives me a unique perspective, an insight into how owners and pilots think and what drives them.

Working Together to Achieve Goals

In a perfect world, owners would think more about pilots and work with them to help them achieve their goals. That means helping them learn, offering them variety in their flying work, and paying them properly for their experience and skill levels.

At the same time in that perfect world, pilots would think more about owners and work with them to help them achieve their goals. That means flying safely and professionally, following FAA (or other governing body) regulations, pleasing clients, taking good care of the aircraft to avoid unscheduled maintenance and repair issues, and helping to keep costs down.

What do you think? Are you an owner or pilot or both? How do you see yourself working with others? Got any stories to share? Use the comments here to get a discussion going.