An essay from years ago.

Let me start with an introduction.

Thanks to the enthusiastic encouragement of a local writing group I joined a few months ago, I’m working on a book project about my flying experiences.

I’d started a book about flying back in 2010, intending to document my first 10 years as a pilot, but set it aside when life got busy with other things. Then, when my crazy divorce started, I forgot all about it. Rebooting my life in a new place and building a new home kept it on the far back burner of my mind. I recently discovered the manuscript on my computer’s hard disk and submitted one of the stories to the group. They seemed to love it and asked for more. With an overabundance of free time during the winter months, it seemed like a good idea to dive back in and possibly get it ready for publication by this spring.

I spent most of yesterday learning to use Scrivener, the writing tool of choice among so many of my writing friends. I moved the manuscript into Schrivener and organized the existing content into subchapters while expanding the outline. Then I continued the process of tracking down old blog posts to form the basis of stories that would make up the subchapters for the book.

I have a lot of blog posts about flying.

Although many of the early posts never made the transition from my original iBlog-based blog to the WordPress-based blog I started in January 2006, some of them did. Among them is a post called “The Big, White Tire,” which I wrote on November 6, 2003. (Yes, I’ve been blogging for more than 12 years now.) Near the beginning of that post, I wrote:

In my essay, “When I Became a Pilot” (which has since been lost in various Web site changes), I discuss the various flights I’ve made that have led up to me finally feeling as if I really am a pilot. One of these flights was my private pilot check ride. And in one of those paragraphs, I mention the big, white tire.

I got curious about the essay. Was it really lost? When had I written it? Was it possible that it was on my computer somewhere, hiding in plain sight?

So I did a computer search for “when I became a pilot” and found a Word document with the same name. It was the “missing” essay.

Here it is.

When I Became a Pilot

I became a helicopter pilot this past year, although I’m not sure exactly when.

It wasn’t the day I took my introductory flight. That 0.9 hours on the very first line of the very first page of my logbook isn’t even a clear memory to me. I know my instructor, Paul, and I left Chandler Municipal for the practice area at Memorial field, as we would do for most lessons over the course of my private pilot training. I assume he spoke to me about flying and I have a vague memory of handling the controls, although not all of them at once. I certainly wasn’t a pilot that day.

It wasn’t the day I first soloed, after months of squeezing hour-long training flights into my busy schedule. I remember that day clearly. After doing a few traffic patterns at Memorial, Paul told me to set down. He had a hand-held radio with him and he tuned it and the one in the helicopter to the frequency the flight school used.

“Now when you pick up,” he told me, “the front left skid will lift off first. You’ll have to compensate with forward and left cyclic. Do a few traffic patterns. Make all your radio calls. I’ll be listening and keeping an eye out for traffic.”

He lowered his head as he walked away from the helicopter and its spinning blades. Then he stood facing me, only thirty feet away. I could see his face clearly.

“Go ahead,” his voice came though the radio.

I pulled the collective up slowly. The helicopter became light on its skids. Then the left skid came up while the helicopter seemed to tip backwards. I panicked a little and jerked the collective up. The helicopter popped up ten feet. Paul’s eyes opened wide and his face displayed his concern. I’m sure mine did, too.

I did three or four patterns, landing near him on the cracked asphalt of the runway on each pass. Then he told me to set it down and he got back in. I could tell he was proud of me. (He told me later that the reason he remained a flight instructor so long was because he felt a real sense of achievement every time a student soloed for the first time.) But I still wasn’t a pilot.

It certainly wasn’t the day I did my first cross-country flight. Paul and I had planned the flight and I had circled all the waypoints I expected to see. The chart was folded and strapped to my leg with the flight plan clipped on top of it. It was a warm day in April and the doors were off. But the late afternoon thermals were brewing as we flew south to Eloy and they were particularly nasty as we flew over the Santan Mountains. That’s when I started feeling sick.

Studying a map on my lap while the helicopter bumped through rough air was too much for me. I found all the waypoints and we stayed on course, but about ten miles short of Gila Bend, our second stop, I’d had enough. I asked Paul to take over.

I didn’t get sick. Keeping my eyes on the horizon and off the damn map saved me. I was able to land at Gila Bend. Paul decided we should get out and walk around a bit, so we shut down on the ramp near a small building. Inside was a table, a few chairs, and a soda machine. We bought Cokes. A Mexican man was sitting at the table, patiently cutting the spines off young cactus pads that were neatly spread out in a flat cardboard box. Napolitos. We spoke briefly to him; he didn’t speak English very well.

A while later, we were back in the helicopter, starting up. The wind was howling. I felt Paul’s steadying grip on the controls as we took off. We had a tailwind, and according to the winds aloft information I had, it might be even stronger higher up. So instead of flying back at 500 AGL, we climbed to 2000 AGL. According to the helicopter’s GPS, we had a ground speed of 103 knots. The airspeed indicator read about 85. We were in a hurry to make up for lost time, so we let the wind help us out. I learned a lot about flying and the remote airports of Arizona that day. I also learned not to study a map strapped to my leg while I was flying in bumpy air. But I still wasn’t a pilot.

I found this photo in my logbook case pocket. My flight instructor, Paul, snapped this right after I passed my first check ride in April 2000.

It wasn’t the day I took and passed my private pilot rotorcraft helicopter check ride, either. At that point, I was flying out of Scottsdale, which was a bit closer to home. Although more than a year had passed since my first lesson, Paul was still my instructor. I’d spent the whole week at Scottsdale, staying at a local hotel, flying during the day and studying at night. I think I did more autorotations that week than I did in all my months of training.

The oral part of the check ride went pretty well. The examiner was the flight school owner and he did a good job putting me at ease. Then we went out to fly. I don’t remember much, but I do remember thinking that I was flying pretty badly. I didn’t think I’d pass.

I think it was the tire that killed my meager confidence. It was a huge truck tire, painted white. It was out in the desert and one of these days I’m going to go find it. The examiner told me to hover up to it, facing it. Then he told me to hover around it, facing it the whole time. I did a terrible job, and I couldn’t even blame it on the wind.

I was feeling pretty bad by the time we went back, certain I’d failed. But I did make the absolute best approach and landing I’d ever made to the confined space we parked in at Scottsdale. Maybe that’s what saved me. Or maybe my performance wasn’t any better or worse than most student pilots on their check rides. I passed. When the examiner shook my hand, he told me I was a pilot.

But he was wrong. I wasn’t a pilot yet.

I knew I wasn’t a pilot the following month, when I took my first passenger for a ride. We’d rented the same helicopter for two hours. We drove the 70 miles to Scottsdale to pick it up and I did my preflight as I had so many times before. It was warm and the doors were off. I took off and headed back toward home. The plan was to fly over our town, then bring it back. We had just enough time and fuel to make the trip without rushing.

Although the air wasn’t any more turbulent than it had been on my check ride or when I flew with Paul, it seemed different. I was sharply tuned to the sound of the rotor blades, which changed based on their pitch and the pockets of air they sliced through. It seemed to me that there was an unusual amount of blade slap. My passenger, Mike, was also tuned to the sound and it made him nervous. He held onto the doorframe. He made me nervous. I made myself nervous.

It wasn’t a bad flight, but it wasn’t a good one, either. I wasn’t any more a pilot than I had been during my check ride.

I know I wasn’t a pilot when I started my commercial pilot training at a flight school in Prescott. My new instructor, Raj, didn’t baby me. When he realized that I was afraid to fly in heavy wind, he made me face my fear by having me spend twenty minutes on a very windy day, practicing hovering. I remember the lesson well; it was the first time I’d ever been told to make a hover turn using only one foot on one pedal.

My first helicopter, an R22 Beta II, in a friend’s driveway in Aguila, AZ not long after I got it.

I still wasn’t a pilot when I bought my helicopter, a 1999 Robinson R22 Beta II with only 168 hours on its Hobbs meter. I’d gone back to my first flight school and had a new instructor there, Masohiro. He flew with me around the Phoenix Sky Harbor surface airspace to show me how I could fly from Chandler to Wickenburg without talking to ATC. Then I was on my own, to fly Three-Niner-Lima home with Mike.

I don’t recall feeling nervous that day, although I’d logged less than ten hours since our first flight together from Scottsdale five months before. I don’t recall him seeming nervous either. Perhaps I was overwhelmed by the significance of what I was doing: flying my own helicopter.

But I certainly didn’t feel like a pilot a few days later when I flew solo for the first time in over a year to bring Three-Niner-Lima back to Chandler. (I was leasing it to the flight school and I only got it on weekends.) As I took off from Wickenburg, I choose a poor departure route, over the hangars, and for a brief moment, I thought I wouldn’t clear them. (I haven’t done that since.) And I was nervous all the way down to Chandler.

I didn’t feel like a pilot the following month, when I checked out to rent a helicopter in St. Augustine, FL. I wanted to take my stepfather for a ride. The autorotation I did for the flight instructor who checked me out, Ziggy, was so bad, he asked for another one. It must have been okay, though, because they let me rent it. But I wasn’t a pilot yet.

I almost felt like a pilot the month after that, when I participated in a Young Eagles rally in Aguila, AZ. I followed all the rules and worked with a ground crew to give safe rides to five kids. I told them about the helicopter and answered their questions. I knew what I was talking about and what I was doing. And it was clear that everything there thought I was a pilot. But I still wasn’t sure.

I didn’t feel much like a pilot a month later, though, after making my first bad decision regarding weather. The weather forecast called for ceilings of 900 feet along my route from Wickenburg to Chandler and I figured that was enough, since I normally flew at 500 AGL. We took off to the south and soon discovered that the ceilings were lower than expected. They seemed too low along my preferred route, so I decided to take my backup route, which looked a little better. Soon, they were low there, too, and I was flying at 350 to 400 feet AGL, with wisps of cloud bottoms passing the cockpit bubble. The ceilings rose when I was halfway there, but then the rain started to fall. The temperature dropped to freezing and I began to wonder about icing on the blades. The visibility deteriorated to about three miles—still within minimums. But to a fair-weather flyer like me, it seemed as if I were flying in a fog.

I was just about to set it down in the desert and wait out the weather when I picked up Chander’s ATIS and was encouraged by the ten mile visibility it reported. I was five miles out and still couldn’t see the airport, but I followed the familiar route in. I was glad to be on the ground. And fortunately, my passenger—who was from the San Francisco Bay area and accustomed to such weather—never knew about my concerns.

Two months later, on my first long cross-country trip, I realized that I still wasn’t a pilot. I stretched my fuel supply almost to exhaustion with 2.9 hours of flight time. I must have been running on fumes when the fuel guy in Boulder City put 28.5 gallons into a pair of tanks that hold 29.7 gallons. Another few minutes of flight and the Low Fuel (or “Land Now”) light would have come on—possibly while still over Lake Mead.

But a week later, I certainly felt like a pilot. The comment in my log book for that 1.2 hour flight says simply “Yarnell Hill!” I’d followed the Hassayampa River north through the Weaver Mountains and into the valley beyond. Then I’d followed Waggoner Road to Route 89 and followed that to the town of Yarnell. At about 4,500 feet elevation, Yarnell is nestled near the edge of a cliff that the locals call Yarnell Hill. Beyond it, the earth falls away to the Sonoran desert floor near Congress, 1,500 feet below. Worried about the possibility of downdrafts, I’d approached the cliff edge at about 6,000 feet MSL. But the air was smooth. As I cleared the cliff, I lowered the collective almost to the floor and entered a sort of “powered autorotation.” Gliding down at the rate of 1500 feet per minute at about 80 knots airspeed, I got the most amazing rush. I pulled in the collective gently to level off at 3500 MSL feet over the dairy farm, close enough to smell the manure. Now that was flying!

A few off-airport landings for the $200 hamburger also made me feel not only like a pilot, but like a helicopter pilot. My favorite spot is Wild Horse West, about a mile east of Pleasant Valley Airport near Lake Pleasant. I line up with the old pavement of what used to be Route 74 (before it was moved to bypass the restaurant) and land near the entrance to the parking lot. Then I hover-taxi off the road into a clearing where Three-Niner-Lima will be out of the way. A helicopter near the parking lot turns a few heads, but I haven’t gotten a parking ticket yet.

Of course, a new flight instructor who was impossible to please didn’t make me feel much like a pilot at all. I reached new levels of frustration, not long after my departing instructor told me I was ready for my commercial check ride. The only thing that impressed the new guy was my GPS skills—a fact he noted boldly in my student folder. I decided to complete my training elsewhere.

I started feeling like a pilot again when my friends Mark and Gary gave me some formation flying lessons. It was June and I was scheduled to fly along with the world’s largest airworthy biplane (piloted by Mark) to AirVenture in Oshkosh the following month. Gary took off in his Cub and we took turns being lead and wing. It was tough flying slow enough for him to keep up with me when I was lead—and Mike complains that helicopters are slow! I wish I could have seen what we looked like from the ground. I bet it was a sight to see.

The Oshkosh trip fell through but I came up with another cross-country alternative: Colorado. I took a leisurely three-day solo flight, logging 7.0 hours of flight time to Eagle County Airport. Maybe it was that trip that made me a pilot. I learned a lot about flight planning, mountain flying, and weather. And I saw so much! Of course the ride home was tough, especially the 6.1 hours logged in one day, flying from Moab, UT to Wickenburg, AZ with my friend Janet. Heavy departures from high altitude airports, multiple fuel stops, and turbulence combined to make it a flying day I’d rather forget.

But a few months later, I was again doubting whether I was really a pilot.. I had to fly Three-Niner-Lima from Wickenburg to Long Beach, CA to finish my commercial training, and I didn’t think I could do it alone. A private pilot from the flight school took a commercial flight to Phoenix to make the trip to California with me. He wanted to build time; I wanted someone to guide me through the complex Los Angeles area airspace. But when he took the controls on the leg from our lunch stop in Chiraco Summit to our fuel stop at Banning, I knew I was more a pilot than he was. He couldn’t maintain airspeed and let our ground speed drop as low as 52 knots in a 20 knot headwind. Cars on I-10 were passing us! I took control again from Banning to El Monte and showed him how to push into the wind.

I finished my commercial training in just over a week and passed my commercial check ride. (So much for the opinions of difficult-to-please flight instructors in Chandler.) Was I a pilot then? Maybe. Or maybe I became one on the way home the next day. I had to navigate from El Monte to Wickenburg, alone with a late start, handling all radio communications. I had to request special VFR clearances to fly through two Class D airspaces. I had to decide whether to spend the night at Thermal, near Palm Springs or push onward to reach Blythe or Parker before nightfall. I made all the right decisions and had a good, safe flight. I even enjoyed the overnight stay at Thermal, where the FBO generously gave me a brand new car for transportation to and from the hotel.

This trailer landing was a piece of cake compared to the platform I regularly land my R44 on at home these days.

I must have been a pilot when I took my first two paying customers up for rides a few weeks later. Or when Mike and I flew to Falcon Field for dinner at Anzio’s and enjoyed the light of the full moon on the otherwise dark trip back to Wickenburg. Or when Mike’s cousin Ricky and I landed at Swansea, in the middle of nowhere, to explore the ghost town’s ruins without making the five hour round trip car ride. Or when I landed Three-Niner-Lima on the back of a 8×16 flatbed trailer so I could show it off in the Wickenburg Gold Rush Days parade. Or when I stayed on the controls with Mark so he could try out a few maneuvers in the only type of aircraft he’s not rated to fly.

Things felt right during all those flights. I felt confident and my passengers had confidence in me. I didn’t do anything foolish, anything I would scold myself for later on. I was still learning from every flight, but I felt that I had built a solid base of knowledge and skills to fly safely—and enjoy almost every minute of it.

But maybe it was the flight that gave me the idea to write this article. It was just the other morning. I’d gone to the airport at 6 AM and had Three-Niner-Lima out on the ramp and preflighted by 6:30. A few minutes later, we were airborne, just me and my ship, headed south.

The doors are off, the cool morning air rushes through the cockpit. The radio is strangely quiet; am I the only person aloft on that normally busy shared frequency? We pass over the top of Vulture Peak, then make a steep descent and continue south and then west, riding along Aguila Road toward Aguila. Trucks hauling rocks make lines of dust in the distance; soon I’m flying right over one of the trucks on the road. A manmade structure atop a mountain to the south of us catches my eye and we go to investigate. Just a radio tower, but down in the foothills, the ruins of a mining building. A good place to land nearby; I mark it on my GPS for investigation with Mike when the weather cools down. Weaving around the mountains, circling around, looking for anything interesting in the empty desert. There’s the mountain near where we found that saguaro skeleton several years ago. And there’s the old quarry we saw later that day. I mark a few other interesting points, then look ahead. Harquahala looms huge in front of me, rising 3,500 feet from the desert floor. I decide to climb, to see if any other early riser has made the 11-mile, 90-minute journey by four-wheel-drive vehicle to the top of the mountain.

I reduce speed to 60 knots and climb at 500 feet per minute. The ground falls away through my open door and the world spreads out as I gain altitude. It’s a clear, calm morning and I can easily see 50 miles or more in any direction. I notice a road along the ridge that I’d never noticed before. Then I begin to pick out the details at the top of the mountain: the antenna array, the solar panels, and the remains of the Smithsonian Solar Observatory. But the observatory is partially demolished and covered with scaffolding. I circle and check the windsock. There’s no wind. I land at the tiny helipad.

I’m the only human being on top of the mountain that morning as I get out to explore. The observatory is undergoing renovations. I sign the guest book, noting that I arrived by helicopter. Then I walk around, enjoying the silence of the mountaintop and the views all around me. For a while, I feel perfectly in tune with the world.

Time slips away and I have to leave to be back in time for an appointment at 9:00. I climb back into Three-Niner-Lima and start the engine. I bring it up into a hover, then move forward, toward the edge of the cliff. Once clear, I push down the collective and go into a steep glide, following the canyons around to the back of the mountain, where the dirt road winds down to the valley floor. I level off at three thousand feet, then make my way back to Wickenburg.

As I put Three-Niner-Lima back into the hangar, I know that I’m finally a pilot.

After reading this, I pulled out my original logbook and searched for the flight to Harquahala, the one that made me realize that I was a pilot. It was on May 29, 2002, about two years after I got my private pilot certificate. I logged 1.6 hours for that flight and, at that point, had less than 300 hours logged as a pilot in command.

I remember that flight as if it were just yesterday — flying around the desert, then climbing to the top of the tallest mountain in the area and setting my little R22 down on the tiny helipad up there. It was dead quiet that morning and I felt like I was the only person in the world. It was still cool that early in the day and I could see for miles. There was something magical about it.

Of course, there would be many, many magical flights to come.

Anyway, I thought I’d rescue this essay and put it on my blog where it belongs. Consider it a taste of the book to come.

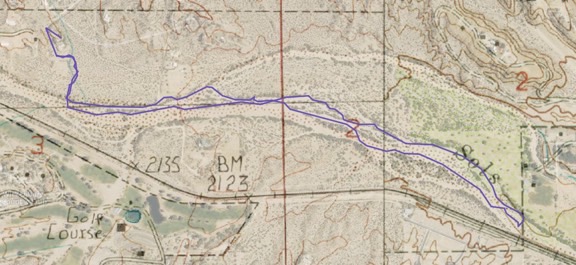

I’d done the walk last week when my friend Janet was in town with her dog. We’d walked about three miles — almost all the way into town and back. Today, I did almost the same walk alone with the dogs. Total trip was 2.58 miles in under an hour. My Gaia GPS trip computer shows the details. You can see the steady but gentle downhill walk and the climb back. Elevation change was only 74 feet — no big deal. You can also see where I rested along the way back.

I’d done the walk last week when my friend Janet was in town with her dog. We’d walked about three miles — almost all the way into town and back. Today, I did almost the same walk alone with the dogs. Total trip was 2.58 miles in under an hour. My Gaia GPS trip computer shows the details. You can see the steady but gentle downhill walk and the climb back. Elevation change was only 74 feet — no big deal. You can also see where I rested along the way back.