Why should I?

Early this season, back in November 2009, I realized that if I wanted my helicopter charter business to succeed, I had to move it out of Wickenburg. That meant finding a secure and affordable hangar in the Phoenix area for the times I expected to do business down there. The plan was for my helicopter to split its time between its Wickenburg hangar and one down in Phoenix or Scottsdale, where my customers were.

After making a few calls and visiting a few airport FBOs, I got what I considered a very good deal from Atlantic Aviation in Deer Valley. For less than I pay for my [admittedly large] hangar at Wickenburg, my helicopter would be stored in a spotlessly clean corporate hangar* only steps away from the terminal building at Deer Valley Airport. If that wasn’t enough to sell me, Atlantic’s line crew would move the helicopter in and out for me at no extra cost. And I’d get a significant discount on fuel purchase. Fuel, of course, was delivered to my aircraft from a truck, so I didn’t have deal with dirty fuel hoses and temperamental fuel systems and the occasional “Out of Fuel” sign.

Sounds good, huh? Well it gets even better.

Nearly everyone at Atlantic knows me by name and greets me with a friendly smile and cheerful “Hello!” When I come in from a flight, the folks at the desk offer me (and my passengers) bottles of icy cold water. The restrooms are sparkling clean and — can you imagine? — always have soap, paper towels, and a clean, fresh smell. If I need to wait for a passenger to arrive, I can do so in a comfortable seating area while watching whatever is on the high definition, flat screen television. If I need to park my good car at the airport for a few nights, they’ll take it inside the airport fence for me and park it in a secure area, where I don’t have to worry about airport lowlifes tampering with it.

On the rare occasion when I do have a complaint — the only time I can think of is when my dust-covered helicopter was taken out in the rain for a few minutes and all that dust turned into big, ugly rain spots — my complaint gets handled quickly, to my satisfaction, without any further ado. With an apology that’s meant. It’s like they realize they have a responsibility and they’re ready to take care of what they need to. (In the instance of my helicopter, they actually washed it for me.)

So to summarize: at Deer Valley I get great service from friendly people who know how to do their job. Getting my helicopter out on the ramp, fueled, and ready for me to preflight and fly is as easy as making a phone call. My monthly rent is reasonable and I get a discount on all fuel purchases.

How much of a discount? Funny you should ask. I’m currently paying about 50¢ less per gallon for full service fuel at Deer Valley than I am for self-serve fuel in Wickenburg. Since I burn about 16 gallons per hour, that saves me $8 every single hour I fly. Since I fly 200 hours a year, that can save me $1,600 over the course of a year. (Ironically, when I ran the FBO at Wickenburg, I was the single biggest buyer of fuel in 2003.)

But it’s not just the money I save that has me buying nearly all of my fuel at Deer Valley these days. It’s the service. That’s something you simply can’t get these days in Wickenburg.

Think the situation at Deer Valley is unusual? Then look at yesterday. I had a charter originating at another Phoenix area airport — one I rarely use. When my passengers arrived, I immediately noticed that one of them had trouble getting around. Since the helicopter was parked quite a distance away from the terminal, I asked the guy at the desk if they could run us all out to the helicopter in their golf cart. No problem. They had the cart ready at the ramp before we even reached it. When I returned from the flight, a quick call on the radio had the cart back in position before my blades had even stopped. But the kicker? When I discovered that the per gallon price of fuel was a penny higher than it was in Wickenburg, I asked for a discount. And even though I only bought a total of 43 gallons (10 before the flight and a top-off after it), they took off 20¢ per gallon.

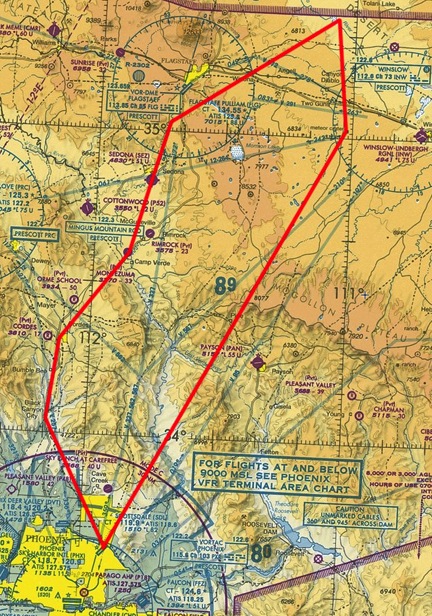

Other airport FBOs also provide real service. Scottsdale’s Landmark Aviation greets me with a golf cart, offers me and my passengers bottles of water and fresh-baked chocolate chip cookies. On a recent trip, they even arranged ground transportation for my passengers. I get service at nearly every airport I go to: Falcon Field, Sky Harbor, Glendale, Sedona, Grand Canyon, Page, Monument Valley, Flagstaff, Winslow, Lake Havasu, Bullhead City, Parker — the list goes on and on.

Except Wickenburg.

Wickenburg’s terminal building is kept locked up tight unless they’re expecting a jet. There’s no one there to greet you — let alone smile at you. The bathrooms, which are accessible via keypad-locked door, are usually dirty and seldom have soap. There’s no counter to set down your sunglasses or purse; the moron who redesigned them obviously cared more about how it would look when new than how functional it might be. There’s no comfortable place to wait or to greet passengers. The pop machine is locked up inside the building, so if you’re thirsty, you’re out of luck. The fuel hoses are dirty, the nozzles leak, the static cable has burrs that’ll cut your hand open if you’re not careful. The only fuel truck is for JetA and it’s only available if you call ahead. If no one answers the phone, you’ll be pumping your own JetA, after taxiing your multi-million dollar aircraft up to the self-serve pump. The windsocks aren’t replaced until they’ve rotted away and the pilots complain. And if you’re in a helicopter, be careful of the FOD on the ramp — some of the short 2x4s they use as chocks tend to become airborne in helicopter downwash.

There’s virtually no airport security and airport management — which barely exists — doesn’t seem to care about the airport’s resident low-life, who vandalizes airport and personal property and steals things from the parked vehicles of people he doesn’t like.

I don’t know any local pilot who buys fuel in Wickenburg if he doesn’t have to. For most of them, though, the issue is price. That’s enough to keep them away from the pumps. I don’t think they expect the kind of service a real FBO offers. They just think Wickenburg charges too much for fuel — and they’re right. How can you charge more that most airports in the state when you don’t provide any services to go with it?

What are people paying for?

I know what I’m paying for. And I’m not buying it at Wickenburg Airport.

—

* To be fair, Atlantic’s hangar in Deer Valley is a shared hangar. The only thing I can store there is my helicopter, its ground handling equipment, and a storage locker for small items such as the dual controls, life vests, and extra oil. It’s not as if I’m getting a cheap private hangar; I’m not. This is, however, what I need on a part-time basis, so it works extremely well for me.

Things seem different lately, and I’m not sure why. I’ve begun getting fan mail from readers of my articles in Aircraft Owner Online (AOO), an online magazine for aircraft owners (duh). The articles are mostly recycled and refreshed blog posts and, to date, are all at least five years old. The folks at AOO do a great job of laying out my text with the high resolution photos I provide, making a slick presentation of my work. (They do the same for the rest of the magazine, of course.) I enjoy preparing and submitting the pieces, mostly because it gives me an excuse to dig back into my archives and relive the flying experiences I’ve written about. The AOO editors barely touch my prose, so I don’t have any reason to complain about heavy-handed editing. It’s a truly positive experience all around.

Things seem different lately, and I’m not sure why. I’ve begun getting fan mail from readers of my articles in Aircraft Owner Online (AOO), an online magazine for aircraft owners (duh). The articles are mostly recycled and refreshed blog posts and, to date, are all at least five years old. The folks at AOO do a great job of laying out my text with the high resolution photos I provide, making a slick presentation of my work. (They do the same for the rest of the magazine, of course.) I enjoy preparing and submitting the pieces, mostly because it gives me an excuse to dig back into my archives and relive the flying experiences I’ve written about. The AOO editors barely touch my prose, so I don’t have any reason to complain about heavy-handed editing. It’s a truly positive experience all around.

At the end of 2008, I finished — that is, completely filled — my first Jeppeson Professional Pilot Logbook. The book documents the first eleven calendar years of my pilot experience.

At the end of 2008, I finished — that is, completely filled — my first Jeppeson Professional Pilot Logbook. The book documents the first eleven calendar years of my pilot experience.