Moving forward, looking ahead.

2014 is over. It was a good year for me. Not my best, but certainly one that finished on a very positive note. A year I can look back on and be proud of what I learned and accomplished, a year that marks the successful end of a long and bitter battle to keep what’s rightfully mine.

The Journal

Penny the Tiny Dog lounges in the morning sun on the wrap-around porch of the house we spent the winter in.

I kept a journal for much of the year. I started it on January 1, 2014, when I was housesitting for a neighbor who was gone for the winter. He had a wonderful home and I was fortunate to be able to spend nearly three months in its comfort. Having the space to entertain friends helped me build stronger bonds with people I’ve met since relocating permanently here in Central Washington State in late May of 2013. And it was a hell of a lot warmer than my RV would have been.

This was the first time I kept a journal for any length of time. You might argue that this blog is a journal — and it is, to a certain extent. But while my blog posts cover a wide range of topics and often go into wordy detailed descriptions, my journal is brief. I wrote in it every morning throughout the spring, set it aside during the summer, and then opened it again in the fall. I wrote my last entry in the 2014 edition this morning and will start my 2015 book tomorrow.

Each entry is limited to one double-sided page, forcing me to keep things brief. I often refer to blog posts for more detail. My journal entries include a lot of thoughts and feelings that I don’t include in my very public blog. 2014 took up 1-1/3 blank books. Red ones — I really do like red. 2015’s first book will be black because that’s the color I found on sale.

The benefit of this and other journals I’ve kept in the past: I can go back and refer to them to see what was going on during a specific time in my life. This is especially important these days, when I’m trying so hard to discard painful memories from my wasband’s betrayal and the very bitter divorce that followed it. Writing things down gets them on paper and out of my head. Later, when I’m fully healed, I can go back and revisit them with the 20-20 vision of hindsight.

I’ll consult that journal as I write up this year in review.

Travel

I didn’t do much traveling in 2014, although I really enjoyed the few trips I took.

The big trip was to California’s Central Valley. For the second year in a row, I had a frost control contract with the helicopter. Unlike the 2013 contract the 2014 contract paid a much higher standby fee but required me to live in the area with the helicopter. So just as I’d moved the helicopter and my RV seasonally to Washington state for cherry drying when I lived in Arizona, in February 2014, I moved the helicopter and my RV to the Sacramento area of California for frost control.

Penny and I, hanging out at George’s hangar at the airport.

I made some new friends down there — it’s amazing how easy it is to make friends when you’re alone and don’t have to humor a companion who doesn’t seem interested in meeting anyone new. George, a fellow pilot, and Becky, who managed the airport where Penny and I lived, became part of my life for the two months I was there. George and I spent a lot of time flying both his gyroplane and my helicopter. We took my helicopter out to San Carlos Airport for a test flight in an Enstrom 480 and a visit to the Hiller Aviation Museum, where we got a great private tour.

Here I am with George, sitting in the cockpit of a 747 on display at the Hiller Aviation Museum.

The hot air balloon flight comped to me by the pilot was one of the highlights of the trip. I hope to return the favor this spring when I go back.

Other things I did in California: during February, March, and April: hot air balloon flight over the Central Valley, wine tasting with visiting Washington friends in Napa Valley, several “joy flying” flights over Napa Valley and the Sutter Buttes, whale watching at Point Reyes, a visit to Muir Woods, kayaking with the members of the Sacramento Paddle Pushers group in the American River, paddling at Lake Solano, and a visit to the food truck extravaganza in downtown Woodland. I also got to see my friend Rod, who lives in Georgetown, and Shirley, who lives in Carmichael. I really like the area I stayed in and hope that this year’s contract lets me base the helicopter at the same airport.

Penny keeps watch in the kayak’s bow as we head back down the American River in Sacramento with new friends. Not sure why I didn’t blog about this trip; I have tons of photos to share.

I went to the Santa Barbara area of California three times in 2014 to record courses for Lynda.com. In February, I took Penny with me and recorded Up and Running with Twitter, a brand new version of my extremely popular Twitter course. I went back in May, without Penny, to record Word 2013 Power Shortcuts and Up & Running with Meetup. I returned yet again in October to record Word 2013: Creating Long Documents. The first time, I stayed at a hotel in Carpinteria that I didn’t particularly care for. But on the next two trips, I stayed at my preferred hotel on the harbor at Ventura in my “usual room” with harbor view and jacuzzi tub. I really enjoy my trips to Lynda. I work extra hard while I’m there so I finish early and get to enjoy a day at the beach.

The view from my usual room in Ventura isn’t too shabby.

I got to visit the San Juan Islands twice this year. The first time was for a week-long vacation at my friend Steve’s house on Lopez Island. I blogged extensively about that great trip. The second time was for the Thanksgiving holiday weekend with my friend Bob at Friday Harbor, which I also blogged about. I really like the islands but could never full-time live on that side of the Cascades: too much dreary weather. I was lucky at Lopez Island; the weather was very good all week.

My final trip of the year was my annual Christmas trip to Winthrop for cross-country skiing in the Methow Valley. I haven’t blogged about that trip yet but I hope to find time to do so. The Winthrop/Mazama area is the largest cross-country ski area in the country, with hundreds of miles of groomed trails. I feel extremely fortunate to have such a great place to ski only 100 miles from my home.

Penny and I went skiing over the Christmas holiday for the second year in a row.

Trips planned for 2015 include Arizona and California this spring. My autumn and winter travel schedules are still up in the air.

The Big Project

Jeff of Parkway Excavating rolled down my driveway on April 24 to begin prepping the building pad.

When I returned to Washington after frost season, I started the biggest project of my life: the construction of my new home. Earth work on my lot began in April and construction began soon afterward, continuing through the end of June. The building, which would house all of my possessions — including my helicopter, RV, Jeep, Honda car, and Ford truck, jet boat, motorcycle, and ATV — is a pole building I designed with the assistance of the good folks at Western Ranch Buildings in East Wenatchee. With a total of about 4,000 square feet, 1,200 of which is dedicated to living space, it features a four-car garage, an RV garage big enough for my helicopter and fifth wheel RV, a shop area, comfortable one-bedroom home, and a wrap around deck with windows to take in the amazing views of the Wenatchee Valley.

They began roofing the building on June 10.

Yes, this is me dressed up for electrical work: toolbelt, kneepads, and warm clothes. Heat is on but without insulation, the building still gets pretty chilly.

Because I was paying cash for the building and because I was interested in saving as much money as possible, I became not only the building’s designer but also the general contractor and electrician. (I was going to do the plumbing, too, but a local plumber offered me a deal that was too good to pass up.) Because my flying work is seasonal and my writing work is flexible, I had no real trouble getting the work done. I did pause in the autumn after getting the framing and roof insulation done, but decided in November to forego a lengthy trip to California and Arizona for the winter months and go full throttle to finish it up as quickly as possible.

What’s done? The building’s entire shell, including concrete floor is done. All doors and windows are installed. My vehicles, including my helicopter RV, are safely tucked inside for the winter. My shop and RV have all utility services. The living space is framed, the furnace and air handler for my HVAC system are installed and running, the ceiling has its first layer of insulation. The electrical system in the garage and living space are about 80% done.

What’s coming up? The plumber comes next week and, if all goes well with the wiring, I’ll get through the inspections needed to close up the walls by January 15. Then I’ll get the insulation and drywall done and the main space painted. The floors go in next. My appliances, custom kitchen cabinets, granite countertops, freestanding soaking tub, glass block shower walls, and many light sconces are on order and will begin arriving as soon as next week. Cabinets will be installed in mid February, appliances at February month-end, and countertops sometime before the middle of March. In the meantime, I’ll put down my deck and the rails around it. At this point, there’s a very real possibility that I’ll be able to move into my new home by March month-end.

If you’ve never built your own home, you likely have no idea what a joy and trial it is. This is, by far, the most challenging thing I’ve ever attempted. It’s a real pleasure — despite the occasional difficulties — to be able to make my own decisions on every aspect of the project without having to wait for a risk adverse, indecisive, and, frankly, cheap partner to weigh in with his decisions. And I cannot begin to describe how rewarding it is to look around what I’m building and know that it came from my mind, my heart, and my hard work.

I’ll continue to blog about the project throughout the coming year.

Other Accomplishments, Activities, New Hobbies

I got the year off to a slow start, not really doing much of anything new. I guess the biggest deal in the spring was learning to fly a gyroplane and soloing in about 7 hours. George taught me in his little Magni M-16 Gyroplane and it was a blast.

George snapped this photo of me as I taxied off the runway after my first solo flight.

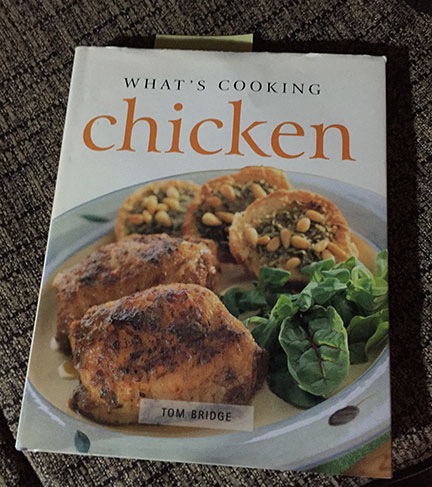

In the spring, when I returned from California, I built a chicken coop and, with the help of some friends, built a secure chicken yard for my flock of six hens. They laid eggs — about three dozen a week! — starting in October and only just slowed down production for the winter. I also had the opportunity to help out at a chicken slaughter.

For the first time in at least 10 years I had a vegetable garden. I planted Brussels sprouts, tomatoes, onions, pumpkins, melons, zucchini, yellow squash, butternut squash, corn, and herbs. Most of my garden occupied pots and raised garden planters I made out of pallets.

I also kept up with my beekeeping activities. I caught a swarm again this year and assisted another beekeeper on a swarm capture. By the end of the season, I had seven hives and had harvested another 3 gallons of honey. I also began selling honey in boutique packaging at local wineries. And I took a mead-making course and put up my first gallon of mead.

Here’s one of my upcycled pendants, created from clear and blue wine bottle glass.

At the end of the summer, I purchased a very small kiln and began doing warm glass projects that upcycled wine bottles into Christmas tree ornaments and jewelry. I began making some of these items available for sale online.

I also stayed pretty active locally during the year, going on multiple hikes, boat trips, paddling trips, and Jeep trips with friends. I took over a Meetup group I belonged to and met a bunch of great people on activities with the group.

Friends

I didn’t realize how many good friends I’d made in the area until I had my moving party on June 28. I sent out invitations in email and on paper and on Facebook and Twitter. The party would be two parts: a moving party that started at my hangar and a pot luck barbecue at my mostly completed home. I honestly didn’t expect more than maybe 20 people to show up with only handful for the move. If I got my furniture moved, I’d be thrilled — I could always fetch the boxes myself.

But the attendance — especially at the hangar — blew me away. At least two dozen people showed up there with pickup trucks. One even brought a large horse trailer. Within 2 hours everything in the hangar was loaded up and we were on our way across the river to Malaga. They unloaded even quicker — almost before I realized what was happening. Then they brought out their pot luck dishes and we partied. I think the final party attendance was close to 50.

My social life here in Washington is amazing. If I wanted to, I could do something with friends every day or evening. Wine tasting, boating and paddling, hiking, Jeeping, dinner, movies, parties — there’s no end to it. On some days, I have to choose between activities or squeeze multiple activities with different people into my day. I’ve never been so active with other people. I love it — especially since these are all great, friendly, generous people who like me for who I am.

And yes, I’m dating, too. But not much, and that’s by choice. I’m extremely picky about starting a relationship with a man. I’d rather live life alone than live it with the wrong man again.

Flying Work (and Play)

In addition to the very lucrative frost contract I had in California in early spring, I had my best cherry drying season ever. In 2014, during the “crunch period” of mid June to mid July, I had three other pilots working with me to cover the acreage I was under contract for. I think we did a remarkably good job providing service for my clients in the Quincy and Wenatchee areas. There wasn’t quite as much rain as there was in 2013, but with more acreage to cover — almost 350 acres at one point! — the standby pay made our dedication to staying in the area worthwhile.

I did some charter work during the season, including a winter video shoot for one client that included air-to-air footage of the historic Miss Veedol airplane and an interesting dawn shoot over the Wenatchee Symphony Orchestra playing at Ohme Gardens. The Miss Veedol footage was only part of the aerial footage shot from my helicopter that appeared in the first We Are Wenatchee video. I also did two amazing Seattle video shoots — at sunset and dawn the following day — as well as a video flight up the Duwamish Waterway and Green River to its source near the base of Mt. Rainier. It’s flights like these that make me so glad I became a helicopter pilot.

We are Wenatchee from Voortex Productions on Vimeo.

Although one of my big charter clients wound up opening its own flight department with a leased helicopter and full-time pilot, I still did a bunch of charter work for them, flying management team members to various orchards throughout Central Washington State — and even to Seattle. They’ll continue to use my services on an as-needed basis during the busy season, as long as it doesn’t conflict with my cherry drying work.

Other interesting flights include a handful of wine tasting flights, a flight to the Slate Peak communication facility, a pollination flight, and two Santa flights. And, of course, I can’t forget my flight to and from Lopez Island and the flight around the San Juan Islands I took with my friend Steve. Or those Napa Valley flights. Or the flight for a hamburger at Blustery’s Drive In in Vantage.

There was still snow atop Slate Peak in May 2014.

Writing Work

Although writing accounts for only a small part of my income these days, I did do a significant amount of writing work. In addition to the four video courses I authored for Lynda.com (mentioned earlier), I also began writing articles for Lynda.com’s blog.

I also made a new writing contact. Beginning in January 2015, my articles about flying helicopters will begin appearing on AOPA’s Hover Power blog. You’ll find my bio on the About the Authors page there. I’m extremely pleased to be writing about helicopters for an audience beyond blog readers.

As for my blog, it’s readership has pretty much doubled over the past year. I now consistently get between 1,000 and 2,000 page hits each day with visitors from all over the world.

My divorce book, which I blogged about back in April 2013 — has it been that long? — is still being written. I can’t finish it until the divorce bullshit is finally over.

The Divorce Bullshit

A lot of people don’t realize that even though my divorce was finalized in July 2013, it wasn’t over. Not only did my wasband appeal the judge’s decision, but he refused to comply with court orders regarding refinancing our house, which he received in the settlement, and paying me what he owed me. So legal action dragged on throughout the end of 2013 and into much of 2014.

My poor wasband — and yes, I do pity him a lot more than I probably should — got a lot of bad advice from friends and family members. If he’d accepted my very generous original settlement offer — proposed back in November or December of 2012 — he could have saved well over $100K in legal fees and could have kept the house for about 1/5 of its market value, including most of the furniture and other items I would have left behind. And we both could have gotten on with our lives with a minimum of bad feelings. But he took that bad advice, which gave him the idea that he had some sort of legal claim over the business I’d begun building long before we were married and all the assets that went with it. Even when the judge decided he didn’t, more bad advice convinced him to appeal. The appeals court, which handed down its decision just before Thanksgiving, agreed entirely with the original judge. In other words, he lost the appeal.

The result: more than two years of our lives wasted, a life-long friendship shattered with a lot of bad feelings, and more money than I’d like to think about thrown away on legal fees. He could have gotten rid of me — and kept the paid-for house! — for $50K. Instead, it’ll wind up costing him over $200K (including legal fees) and he has to sell the house to pay me. That’s gotta hurt.

My only consolation is that his stupidity and greed cost him far more than it cost me. I’ll recover from the financial setback of the legal battle, mostly because I know how to live within my means and I have substantial retirement investments. My home will be fully paid for within a few years, leaving me as debt-free and financially secure as I was before this all started.

Of course, I’ll actually be far better off than before this started because I won’t be dragged down emotionally by a lying loser incapable of making decisions or taking measured risks to move forward in life.

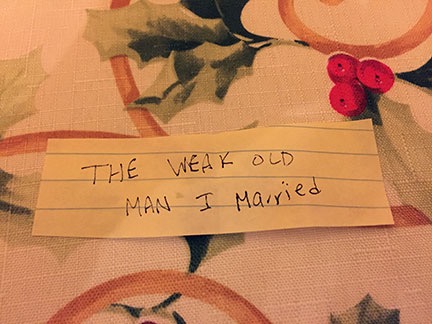

Here’s the note I burned on the yule log at a solstice party — I want to leave this burden behind forever.

And that’s what 2014 has shown me: the 29-year relationship with the man I loved was holding me back, preventing me from moving forward to achieve lifestyle goals and dreams. I thought I shared goals with the man I loved but in the end it was all a lie — he just pretended during those last few years to be on the same page with me to keep the status quo he so loved. He sucked away my self-esteem by blaming me for our dismal social life and making me feel unwelcome in the home he claimed to want to share with me. It wasn’t until he freed me that I regained the self-esteem he’d sucked out of me and I began to move forward with life again.

I’ve accomplished more in 2014 than I had since I married in 2006. I achieved more goals, I made more friends, I learned more things. I stopped waiting for a partner to run out of excuses to hold us back and I began living life again. And believe me, living life alone sure beats the hell out of living life chained to a sad sack old man.

I only wish I’d made the break sooner, before we were married, before he lost his mind and soul. It would have been nice to remain friends with someone I really cared about.

In the meantime, I’m waiting for the house to be sold by a court-appointed master so I can get paid and do my best to put this this nightmare behind me.

After I finish my divorce book.

Looking Forward

2015 promises to be a great year. I have my big construction project to finish up, more writing work ahead of me, and a healthy helicopter charter business to nurture and built. I have more friends than I’ve ever had in my life — good, reliable friends eager to get together for all kinds of fun and even help me make my dreams realities. I have hobbies and interests to keep me busy and plenty of free time to explore them. Best of all, I’m living in a magnificent place that’s full of beauty and life and opportunities for outdoor activities.

Isn’t it beautiful here?

I’m alive and loving life again.

Happy New Year.

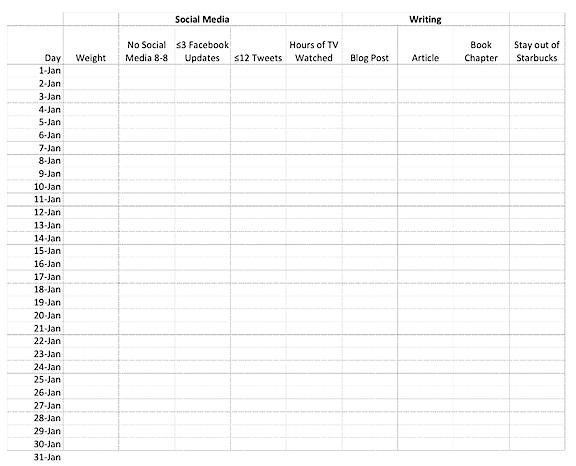

Here’s the first three months of my chart. I stopped tracking my weight on paper when I moved home to Arizona, but got all the way down to 149 pounds (from 196) by the middle of October.

Here’s the first three months of my chart. I stopped tracking my weight on paper when I moved home to Arizona, but got all the way down to 149 pounds (from 196) by the middle of October.

And there is this added cheat: a movie — no matter what length it is — counts as just an hour. But, at the same time, an “hour-long” TV episode watched without commercials, which is really only about 44 minutes long, would also count as an hour. I’ll need a scorecard to keep track. It should be interesting to see how I do.

And there is this added cheat: a movie — no matter what length it is — counts as just an hour. But, at the same time, an “hour-long” TV episode watched without commercials, which is really only about 44 minutes long, would also count as an hour. I’ll need a scorecard to keep track. It should be interesting to see how I do. Yes, I need to lose weight again. Doesn’t everyone?

Yes, I need to lose weight again. Doesn’t everyone? One of the things social media time has stolen from me is writing time. Instead of sitting down to write a blog post or an article for a magazine or even a chapter of a book, I spend that time on Facebook or Twitter or even (sometimes) LinkedIn. Or surfing the web. This are mostly unrewarding, unfulfilling activities. I get so much more satisfaction out of completing a blog post or article — especially when there’s a paycheck for the article.

One of the things social media time has stolen from me is writing time. Instead of sitting down to write a blog post or an article for a magazine or even a chapter of a book, I spend that time on Facebook or Twitter or even (sometimes) LinkedIn. Or surfing the web. This are mostly unrewarding, unfulfilling activities. I get so much more satisfaction out of completing a blog post or article — especially when there’s a paycheck for the article. Why do I go in there? The coffee isn’t even that good!

Why do I go in there? The coffee isn’t even that good! And don’t say it’s the dark chocolate covered graham crackers. Although it could be.

And don’t say it’s the dark chocolate covered graham crackers. Although it could be.