The third of a four-part series about flying at Lake Powell.

Although Lake Powell is simply a beautiful place to overfly, it does have a few specific points of interest that you may want to check out from the air. I’ll cover them in this part of my series, beginning with the downlake points and moving uplake as far as the tour planes go on their standard tours.

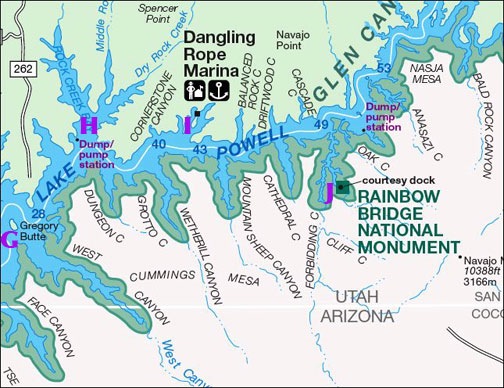

To help you locate these places, I’ve included several maps, each of which has letters corresponding to their descriptions here. This first map is for the downlake points; the map you’ll find a bit farther down in this article is for the points that are farther uplake.

Horseshoe Bend

The first point isn’t even on the lake. Horseshoe Bend (A) is a horseshoe-shaped curve in the river a few miles downstream from the dam. It’s often photographed from the viewpoint at the outside “top” of the bend, which you can walk to from a parking area right off Route 89. Here’s a photo I took today from the overlook.

The first point isn’t even on the lake. Horseshoe Bend (A) is a horseshoe-shaped curve in the river a few miles downstream from the dam. It’s often photographed from the viewpoint at the outside “top” of the bend, which you can walk to from a parking area right off Route 89. Here’s a photo I took today from the overlook.

From the air, however, Horseshoe Bend takes on a completely different look, since you can see all of it at once. There’s an excellent photo of Horseshoe Bend from the air, taken by Mike Reyfman, in Part II of this series.

Keep in mind that this is one of the points visited by the tour planes. They’re normally flying a right hand turn around the bend at about 5500 feet, so be listening for them if you overfly.

Glen Canyon Dam

The Glen Canyon Dam (B) is the dam that keeps all the water in the lake. It’s accompanied by a bridge a few hundred feet downstream that crosses Glen Canyon. From the air, you can get good views of both.

The Glen Canyon Dam (B) is the dam that keeps all the water in the lake. It’s accompanied by a bridge a few hundred feet downstream that crosses Glen Canyon. From the air, you can get good views of both.

Again, remember that the tour planes are also showing off this area. They tend to fly past between 4800 and 5500 feet, right after climbing out from the airport.

Wahweap Marina

Just past the dam, to the northwest, is the Wahweap area of the lake. It’s off the main channel and is home to the Wahweap Resort and Marina (C), currently managed by Aramark Services for the National Park Service. It includes a marina with slips and buoys, a tour boat dock, a rental boat dock, a resort hotel with two pools, and a campground. You can’t miss it.

The tour planes fly in the vicinity, usually at 5500 feet.

Navajo Canyon

Navajo Canyon (D) is an extremely long lake canyon that winds its way to the south. Outlined in white by the “bathtub ring” water line, it makes a fine subject for aerial photography early in the morning and late in the day. What sets it apart from other long side canyons on the lake is its width — it remains quite wide for miles. There’s also a huge sand dune against one canyon wall that’s a popular houseboat overnight spot.

The tour planes overfly this canyon, descending from 5000 feet (or higher) as they return to the airport.

Tower Butte

Tower Butte (E) is the iconic symbol of Lake Powell that you’ll see on various logos, etc. throughout Page. I don’t think it’s anything special, other than the fact that its top would make an excellent (but illegal) landing zone for a helicopter. It’s not even that close to the lake. But at sunset, it makes a good foreground subject for the illuminated cliffs and buttes behind it.

And if you’re flying low-level (think helicopter or ultralight) you might be able to spot some of the ancient ruins along the base of the butte — although I haven’t been able to find them lately.

This is a reporting point for the tour planes, which begin their descent for the airport right around here. Uplake beyond this point, the tour planes are on the uplake frequency (122.75).

Gunsight Butte

Gunsight (F) is a large rock formation that resembles a gun sight. It’s just uplake from Romana Mesa, which is one of the tour plane reporting points. Beyond the butte is beautiful Padre Bay, which has some interesting history and is popular with houseboats.

This photo was taken from the top of Romana Mesa on one of my 4WD outings. In it, distant Navajo mountain is lined up in the “sight” of Gunsight Butte.

Gregory Butte

Gregory Butte (G) stands out in my mind primarily because of its photogenic qualities. If you’re flying uplake early in the day and take a photo up Last Chance Canyon with Gregory Butte in the foreground…well, you get the photo you see here. It’s one of my favorite views of the lake. This shot was taken by my husband on one of our first helicopter trips to the lake together. The water level is a bit higher right now. If it rises some more, Gregory will become an island.

Gregory Butte (G) stands out in my mind primarily because of its photogenic qualities. If you’re flying uplake early in the day and take a photo up Last Chance Canyon with Gregory Butte in the foreground…well, you get the photo you see here. It’s one of my favorite views of the lake. This shot was taken by my husband on one of our first helicopter trips to the lake together. The water level is a bit higher right now. If it rises some more, Gregory will become an island.

This is another tour plane reporting point, as they fly downriver at 5000 or 6000 feet.

Rock Creek

The mouth of Rock Creek (H) is also an extremely photogenic viewpoint. Whether you’re looking up Rock Creek’s three separate canyons or up Lake Powell itself, the view from the air at this point is magnificent. I usually see it from around 4800 feet, which is admittedly low — remember, I’m doing photo flights — but it’s also good from above.

This is one of the turnaround points for tours, so expect a lot of tour plane traffic here. Listen in on 122.75. Traffic coming downlake will be at 5000 or 6000 feet. Traffic turning downlake here will be descending in a right hand turn from 5500 to 5000 feet.

Dangling Rope Marina

Out in the middle of nowhere, on the north side of the lake, tucked into a canyon, you’ll find Dangling Rope Marina (I). This is an important fuel and supply stop for boaters on the lake. What’s odd about it, however, is that it’s only accessible by water. There’s no road in or out of this place. Supplies are brought in on barges and garbage is taken out on the same barges.

Rainbow Bridge

Everyone wants to see Rainbow Bridge (J) from the air. Everyone, that is, except those who know better.

Everyone wants to see Rainbow Bridge (J) from the air. Everyone, that is, except those who know better.

The truth of the matter is, Rainbow Bridge is much better seen from the ground. The trouble is, it’s tucked into a relatively deep canyon that aircraft simply cannot get into safely. From a moving aircraft, you just get a glimpse of the bridge. And if you go too early or too late in the day, the whole thing is in shadow. Not the best experience.

If you’re serious about seeing Rainbow Bridge, get on a boat and take the 2-hour ride from Page to see it from the ground. You won’t regret it.

The Tour Points

Those are the basic downlake points of interest from the air. There are others, but I’ll let you discover them for yourself. As you’ll see when you overfly the lake, the entire lake is magnificent from the air. If it’s your first time visiting, you’ll be too awed to bother tracking down specific places to see. Just take it all in and enjoy.

In the final part of this series, I’ll tell you about some of the interesting points beyond Rainbow Bridge. If you’re flying in the area and aren’t on a schedule, you might want to check them out as well.

Lookout Studio at Dawn

Lookout Studio at Dawn Tree-Framed Dawn at the Grand Canyon

Tree-Framed Dawn at the Grand Canyon Grand Canyon Dawn

Grand Canyon Dawn

The writer is sitting up front beside me, taking notes and using my Nikon D80 to shoot images of what she sees. Although a good portion of the shots have some unfortunate glare — not much you can do about that when shooting through Plexiglas — many of them are really good. Like this shot she took of a herd of wild horses we overflew on the Navajo Reservation two days ago.

The writer is sitting up front beside me, taking notes and using my Nikon D80 to shoot images of what she sees. Although a good portion of the shots have some unfortunate glare — not much you can do about that when shooting through Plexiglas — many of them are really good. Like this shot she took of a herd of wild horses we overflew on the Navajo Reservation two days ago. I’m treating myself to a few of the activities my excursion guests get to enjoy. For example, on Tuesday, I joined the crew for a boat ride on Lake Powell that visited the “business side” of the Glen Canyon Dam before squeezing about a mile up Antelope Canyon (see photo) and gliding up Navajo Canyon for a look at the “tapestry” of desert varnish on some cliff walls. I skipped the Sedona Jeep tour and Monument Valley tour to work with one of the video guys or just rest up. Normally, while my guest are touring, I’m scrambling to get the luggage into their hotel room and confirming reservations for the next day. You might imagine how tired I am after 6 days of playing pilot and baggage handler.

I’m treating myself to a few of the activities my excursion guests get to enjoy. For example, on Tuesday, I joined the crew for a boat ride on Lake Powell that visited the “business side” of the Glen Canyon Dam before squeezing about a mile up Antelope Canyon (see photo) and gliding up Navajo Canyon for a look at the “tapestry” of desert varnish on some cliff walls. I skipped the Sedona Jeep tour and Monument Valley tour to work with one of the video guys or just rest up. Normally, while my guest are touring, I’m scrambling to get the luggage into their hotel room and confirming reservations for the next day. You might imagine how tired I am after 6 days of playing pilot and baggage handler.

The first point isn’t even on the lake. Horseshoe Bend (A) is a horseshoe-shaped curve in the river a few miles downstream from the dam. It’s often photographed from the viewpoint at the outside “top” of the bend, which you can walk to from a parking area right off Route 89. Here’s a photo I took today from the overlook.

The first point isn’t even on the lake. Horseshoe Bend (A) is a horseshoe-shaped curve in the river a few miles downstream from the dam. It’s often photographed from the viewpoint at the outside “top” of the bend, which you can walk to from a parking area right off Route 89. Here’s a photo I took today from the overlook. The Glen Canyon Dam (B) is the dam that keeps all the water in the lake. It’s accompanied by a bridge a few hundred feet downstream that crosses Glen Canyon. From the air, you can get good views of both.

The Glen Canyon Dam (B) is the dam that keeps all the water in the lake. It’s accompanied by a bridge a few hundred feet downstream that crosses Glen Canyon. From the air, you can get good views of both.

Gregory Butte (G) stands out in my mind primarily because of its photogenic qualities. If you’re flying uplake early in the day and take a photo up Last Chance Canyon with Gregory Butte in the foreground…well, you get the photo you see here. It’s one of my favorite views of the lake. This shot was taken by my husband on one of our first helicopter trips to the lake together. The water level is a bit higher right now. If it rises some more, Gregory will become an island.

Gregory Butte (G) stands out in my mind primarily because of its photogenic qualities. If you’re flying uplake early in the day and take a photo up Last Chance Canyon with Gregory Butte in the foreground…well, you get the photo you see here. It’s one of my favorite views of the lake. This shot was taken by my husband on one of our first helicopter trips to the lake together. The water level is a bit higher right now. If it rises some more, Gregory will become an island.

Everyone wants to see Rainbow Bridge (J) from the air. Everyone, that is, except those who know better.

Everyone wants to see Rainbow Bridge (J) from the air. Everyone, that is, except those who know better. If you don’t know what Antelope Canyon is, you’ve probably never read Arizona Highways or seen any of the “typical” Arizona photos out there on the Web. As

If you don’t know what Antelope Canyon is, you’ve probably never read Arizona Highways or seen any of the “typical” Arizona photos out there on the Web. As  Lower Antelope Canyon is downstream from upper. It has far fewer visitors. I think it’s more spectacular — with corkscrew-like carvings and at least two arches — but I also think it’s harder to photograph. It’s also far more difficult to traverse, requiring climbing up and down iron stairs erected at various places inside the canyon, clambering over rocks, and squeezing through narrow passages. For this reason, the Navajo caretakers don’t really limit your time in Lower Antelope Canyon. You slip through a crack in the ground — and I do mean that literally (see photo left) — and are on your own until you emerge from where you descended or from the long, steep staircase (shown later) that climbs out before the canyon becomes impossible to pass.

Lower Antelope Canyon is downstream from upper. It has far fewer visitors. I think it’s more spectacular — with corkscrew-like carvings and at least two arches — but I also think it’s harder to photograph. It’s also far more difficult to traverse, requiring climbing up and down iron stairs erected at various places inside the canyon, clambering over rocks, and squeezing through narrow passages. For this reason, the Navajo caretakers don’t really limit your time in Lower Antelope Canyon. You slip through a crack in the ground — and I do mean that literally (see photo left) — and are on your own until you emerge from where you descended or from the long, steep staircase (shown later) that climbs out before the canyon becomes impossible to pass. I went to Lower Antelope Canyon with my next door neighbor and fellow pilot, Robert, today. It had been a whole year since

I went to Lower Antelope Canyon with my next door neighbor and fellow pilot, Robert, today. It had been a whole year since  We arrived at about 11:20 AM and the place was unusually crowded. But Lower Antelope Canyon is large and everyone spread out. Most folks only made the walk one way, taking the stairs up and hiking back on the surface. We would have done the same, but we ran out of time. We were in there until 2:30 PM; Robert had to be at work by 4 PM.

We arrived at about 11:20 AM and the place was unusually crowded. But Lower Antelope Canyon is large and everyone spread out. Most folks only made the walk one way, taking the stairs up and hiking back on the surface. We would have done the same, but we ran out of time. We were in there until 2:30 PM; Robert had to be at work by 4 PM. We made our way through the canyon slowly, stopping to take photos along the way. Positioning the tripods was extremely difficult sometimes, as the canyon floor was often only wide enough for a single foot to stand in it. My tripod really hindered me, but I made it work. I think Robert (shown here) had an easier time with his. We were two of dozens of photographers, most of which were very polite and stayed clear of other photographer’s frames. This is the biggest challenge at Upper Antelope Canyon. I find it stressful up there, as I told a trio of photographers from Utah. Lower Antelope Canyon is much more relaxing.

We made our way through the canyon slowly, stopping to take photos along the way. Positioning the tripods was extremely difficult sometimes, as the canyon floor was often only wide enough for a single foot to stand in it. My tripod really hindered me, but I made it work. I think Robert (shown here) had an easier time with his. We were two of dozens of photographers, most of which were very polite and stayed clear of other photographer’s frames. This is the biggest challenge at Upper Antelope Canyon. I find it stressful up there, as I told a trio of photographers from Utah. Lower Antelope Canyon is much more relaxing. Near the end of the canyon walk, I was worn out. It wasn’t the hike as much as the struggle to find the right shots and get the tripod into position. I felt as if I’d had enough. So when we reached the last chamber before the canyon got very narrow (and muddy) and I laid eyes on those stairs, I realized it would definitely be better to take the easier route back. I took this shot with my fisheye lens, which was the only way to get the entire staircase in the shot. If you look closely, you can see Robert’s head poking out near the top.

Near the end of the canyon walk, I was worn out. It wasn’t the hike as much as the struggle to find the right shots and get the tripod into position. I felt as if I’d had enough. So when we reached the last chamber before the canyon got very narrow (and muddy) and I laid eyes on those stairs, I realized it would definitely be better to take the easier route back. I took this shot with my fisheye lens, which was the only way to get the entire staircase in the shot. If you look closely, you can see Robert’s head poking out near the top. I took about 95 photos while in the canyon. Some of the better ones — along with some to illustrate the story — are here. There’s a better collection in my Photo Gallery’s new

I took about 95 photos while in the canyon. Some of the better ones — along with some to illustrate the story — are here. There’s a better collection in my Photo Gallery’s new