What I learned at a North Cascades Environmental Learning Center photography class.

I love the North Cascades Environmental Learning Center, which is not far from the Diablo Dam on Diablo Lake on the North Cascades Highway (Route 20). I got my first glimpse of it during a camping trip last summer and later that year returned to take a three-day course about mushrooms. This year, I returned for one night of Base Camp right before an overnight seminar titled “Wilderness Photography: Washington Pass at Night.” Here’s the course description, since I can assume the link to the course page will eventually break:

In the grandeur of the North Cascades, moonless nights with clear skies offer fantastic opportunities to capture vivid images of the galaxy.

Join photographer Andy Porter on this specially-scheduled evening expedition to capture images of the Milky Way on this moonless night. We’ll begin the adventure with a short evening workshop on night photography at the North Cascades Environmental Learning Center. Then we’ll head to Washington Pass where, under the towering peaks of Liberty Bell and the Early Winter Spires, Andy will guide us in capturing our own images of the night sky.

I could go into a lot of detail about my stay at the NCELC and the other things I did while I was there, but I’ll try to stay focused for this post. But I do need to talk briefly about the weather, since it did play a major part in how the course went.

The weather was not very good. It was overcast all day and rained more than a few times. Although the clouds were relatively high, there wasn’t a single clear patch in the sky. It was like this all day, which really didn’t surprise me — it rains every single time I come to this area. I like the rain, mostly because I don’t get much of it at home, but I really wish it wouldn’t rain in the mountains when I’m there.

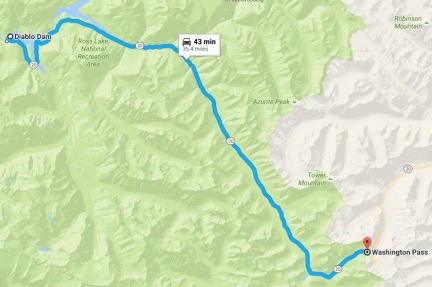

Washington Pass is a 35-mile drive southeast from Diablo Dam on Route 20.

Of course, we weren’t supposed to take pictures in the Diablo Lake area. We were supposed to go to Washington Pass, about 35 miles east. I’d driven through the Pass the day before on my way to the NCELC and it had been partly cloudy, with smoke from a fire I later discovered was burning near Mazama. But the weather information we had showed that Washington Pass was likely just as bad as it was where we were. And there’s nothing worse than making a 70-mile round trip drive to take pictures and not being able to do so.

There was a short classroom session after dinner. Andy introduced himself and showed off a few slides of his work. Most featured an easily identifiable foreground object that was often lighted — like a tent with kids in it or the roots of a fallen log — and a magnificent night sky. He briefly explained how he accomplished the lighted part of the shot by illuminating it for only about a second during the long exposure required to get the night sky. He also admitted to doing a lot of post processing and even showed us before and after shots.

Then he gave us the details on how we needed to set up our cameras for nighttime shooting. Here’s a brief version of his instructions. I’m not giving away any secrets here — all this information is available in a wide variety of places online.

Required Equipment

Before I detail the settings, let me start with the basics. If you don’t have this equipment, you probably can’t do this kind of photography. Or at least I won’t be able to explain how.

- Camera. At the very minimum, you need a camera capable of setting aperture, shutter speed, ISO, and focus manually. Most DSLRs can do this, although lower end models might have limitations. These days, I shoot with a Nikon D7000, but I’m pretty sure my old Nikon D80 could do the job. And yes, a film camera could work, but the ability to immediately see results and adjust settings make it really impractical.

- Wide-angle lens. The wider the field of view, the better off you’ll be. In case you don’t know, the lower the focal length, the wider the field of view. I used a 10-24 mm lens for this shoot and set it to 10 mm. Because I don’t have a full-frame sensor in my Nikon camera, that’s equivalent to a 15 mm focal length. There were people shooting with everything from 10 mm to 28 mm in the class.

- Tripod. You need a good, sturdy tripod. There’s no getting around it. I use a Manfrotto with a ball head and I love its flexibility. If you have options, use one that can be extended so it’s tall enough for you to look through the lens and check image results without having to bend over. Sturdy is especially important if there’s any wind — although this isn’t something you’d likely attempt with anything stronger than a light breeze.

- Cable or remote shutter release. My camera won’t support a cable release, but it does support a remote shutter release, which I have. If you don’t have either, there is a workaround: use the camera’s self-timer to release the shutter. (This is what I wound up doing when my remote crapped out for some unknown reason during the shoot.) Under no circumstances should you be pressing the shutter release button by hand; it will definitely shake the camera, even on a tripod.

What’s interesting to me is that just about all of the people who took part in the class — and I think there were nearly 20 of us — had brought a bunch of camera equipment. I didn’t bring all of mine, but I did bring my camera body and three lenses. In reality, all we needed was what I listed above. So when it was time to get on the van to drive out to our shooting destination, I secured my camera on my tripod, rested the top of the tripod on my shoulder, and left the rest of my gear behind. I like traveling light.

Camera Settings

The tricky part of shooting the night sky is setting up the camera properly. Andy, our instructor, had us do this in the classroom so we wouldn’t be fiddling with settings in the dark. If you set the camera up right in advance, there’s only one thing you might have to change out in the field.

- Widest field of view. If you’re using a zoom lens, zoom out to the widest field of view (smallest focal length number). Again, I used 10 mm.

- Manual focus. This can be a setting on your lens or camera or both. (It’s both on mine.) You definitely do not want the camera trying to automatically focus, especially if your camera won’t make an exposure unless focus is locked in.

- Lock it in!

This is where I really wish I had some gaffer’s tape with me. This is special tape used in film production; it makes it possible to secure things like you would with any tape, but when you pull the tape off, no sticky residue is left behind. This would have been very helpful for me to lock that focus ring down, preventing me from accidentally moving it during the shoot.

Focus to infinity. This is actually a lot trickier than it sounds and it took a while for us to all get it right. Simply dialing the focus ring as far as it goes on the infinity side isn’t necessarily correct. You need to play with it a little at a variety of settings out near the infinity symbol (∞). After each setting, snap a photo of something at least 50 feet away and then check it in the review window. Zoom in to see how crisp it is. Then try another setting to see if it’s crisper. Repeat this process until it’s dialed in perfectly. On my lens, the tick mark was lined up with the center of the infinity symbol but it might be different for yours. If you don’t have focus distance symbols on your lens, you might have to use autofocus to get the right focus setting before setting manual focus. I’m pretty sure that’s what Andy helped a few people do.

- Manual exposure mode. You must set the camera for manual exposure so you’re in charge of how it takes the photo.

- Calculating shutter speed with the 500 Rule

If you want to do the math, it’s pretty simple: 500 ÷ Focal Length ÷ Crop Value

So if you have a high-end camera with a full frame sensor and you’re using a 12 mm lens, the math is:

500 ÷ 12 ÷ 1 = 41.66, which you can round down to 40.With my camera’s 1.5 crop sensor and 10 mm lens, the math is:

500 ÷ 10 ÷ 1.5 = 33.33, which I rounded down to 30.Maximum shutter speed per the 500 Rule. Okay, this is where it gets a little complicated. Andy gave us a handout with a table of settings for the 500 rule, but never explained what the rule was or why it’s important. I did a little research this morning to learn more. We all know that the earth rotates, which means that the stars appear to move across the night sky. They move slowly so we don’t actually see them moving, but if your camera’s exposure is too long, you’ll get star trails — lines made by the stars as their light moves across the camera’s focal plane. To avoid star trails — which is what we wanted to do — you need to set your maximum shutter speed in accordance with the camera sensor size and lens focal length. You can learn more about this on Petapixel, which is also where you can find a table of values. Keep in mind that the shutter speed is in seconds, not fractions of a second. So when I set my camera’s shutter speed, it appeared as

30"in the settings screen. Exposures longer than that require the “bulb” setting on my camera, which means I’d have to manually open and close the shutter based on time I keep with a stopwatch or something. - ISO to 2000. This is a good starting point. Of all the settings, this is the one you might be fiddling with in the dark, so make sure you know how to change it. On my camera, it can be done with a combination of buttons and dials but it’s actually a lot easier to just go into the settings menu. I found that my best shots were done at 5000; more on that in a while.

Widest aperture. Set your lens so it’s wide open (smallest f-stop number). This enables the camera to take in as much light as possible during the exposure. For my lens, that was f3.5.

Shooting

Once we had set up our cameras, we all climbed onto the NCELC’s shuttle bus, filling every seat. Andy took a few people in his car. Although it was difficult to see the sky through the tall trees around the campus, it was still pretty cloudy and none of us had very high hopes of getting good photos. They’d decided to try a closer viewpoint: the Diablo Dam Overlook. This offered views of the main lake and dam, as well as up the Thunder Creek arm of the lake and Colonial Peak. With few trees, we’d have a clear view of the sky.

As we drove over the dam, I was looking out the window and saw a single point of light. “I see a star!” I called out. Other people looked but I’m not sure if they saw anything.

Incredibly — to me, anyway — one of the class attendees had to ask the instructor where the Milky Way was. He could see it, but he didn’t know that that the bright band of stars he was looking at was what’s referred to as the Milky Way — the galaxy our tiny planet is part of. This made me sad. I remember my grandfather pointing out the Milky Way when I was five or six years old, sitting with him on the front lawn of his house in suburban New Jersey, long before light pollution hid it from view. Yet this man, in his seventies (!), had spent so much time in the city that he couldn’t even identify the Milky Way when he saw it in the night sky.

Less than ten minutes later, we were at the overlook, which was understandably deserted. It was well after 9 PM and quite dark. But once our eyes had adjusted after the lights from the bus we saw it above us: the Milky Way.

I beelined it to the corner of the overlook where I’d get a good shot up the Thunder Creek arm. My camera was already on my tripod; all I had to do was extend the legs and neck and get it in position. I might have been the first person to take a shot.

And this is where patience is important. Each of my shots was 30 seconds long. Once the shutter closed, the image did not immediately appear. The camera, which is nothing more than a computer with a camera attached to it, had to process all the information it had just collected. I think this took longer than the exposure time — perhaps as long as another 40 seconds. So from the time I started my shot to the time I was actually able to see it in the review screen at the back of the camera was more than a minute.

A look up Thunder Arm at night. The cars driving by on the road often ruined shots by illuminating landscape features we wanted to be kept dark.

My first shot came out dark. Yes, I could see the stars, but no, I couldn’t see them well. I thought it might have something to do with my reading glasses, which seem to make things look darker than they are. But Andy took a look and recommended bumping up the ISO, which he’d originally advised me to start at 1600. So I tried 2000. It wasn’t much better.

Meanwhile, other photographers were snapping away, emitting occasional oohs and aahs and cursing at the cars that drove past the view point, illuminating foreground items we wanted to be kept dark. One woman near me had very good luck with her camera ISO set to 5000 so I gave it a try. (My camera goes up to over 24000.) That looked much better, so I stuck with if for the rest of the shoot.

Keep in mind that the higher the ISO setting, the more light is processed in the camera. There is a cost to this, however. High ISO settings lead to grainy images or “noise” (digital artifacts) in the images. Ideally, you want to keep the ISO as low as possible to get the shot you want. But since you can’t open the lens any wider (aperture setting) and can’t lengthen the exposure any longer (shutter speed setting), the ISO is the only thing you can change to vary the brightness of your shot.

I moved around to a variety of places. The Milky Way was mostly overhead, but it did dip down to the horizon in the south. A handful of light clouds drifted by, sometimes obscuring stars.

I took a few shots of the dam. The lights reflected off the clouds, reddening them. I think this is the image where digital noise is most apparent, especially in the clouds. (A few people mistook the reddish clouds in their pictures for the aurora. Sorry, but no.)

We shot for well over an hour. I captured about 40 images. I haven’t looked at all of them on my big computer yet; these are pretty much decent random images I grabbed for this blog post. All of these are edited to make the stars “pop” more than they do in the original. If you have good image editing skills, you’ll definitely use them if you do night sky photography. I prefer to minimize editing.

This was shot almost straight up. I think the trees and clouds offer a sense of three dimensionality.

For the most part, the photographers were good to work with. The only real problem we had was with light — too many of them wore headlamps. The trouble with headlamps is that they point wherever you look. So if you look up, your light flashes up, possibly illuminating trees or other foreground object people want dark. This got a bit frustrating and, more than a few times, I called out, “Lights down, please!” One photographer seemed to think that no lights should be on at all and rudely yelled at anyone who used a light, even if it was pointed down at the ground. Sorry, but when walking on uneven terrain in the dark I’m going to use a light — in my case, my phone’s flashlight. If the light doesn’t shine on the subject, it should not affect the photo.

The End of the Shoot… and Beyond

We went back to campus in two groups. I was in the first one. I’d had enough. My remote shutter control had died about halfway through the shoot and I had to rely on the camera’s self-timer to activate the shutter, adding another 20 seconds to each shot. I was burned out and, unlike most of my companions, I live in a dark sky area and can try this again anytime, right at home.

There was no follow-up lesson — although I really think there should have been the following morning. A chance to review and critique what we’d done. I did spend some time at breakfast with other students and got signed up for a Washington State Astrophotography group on Facebook. I’ve already swapped photos and comments with a few classmates there.

Could my images be brighter? I think so. Next time I try this, I’ll do more experimentation with ISO settings. I might need to pop it up some more.

And yes, there will be a next time. I’m thinking of giving it a go on my deck tonight. And I’m definitely looking for companions on overnight outings, possibly with the Turtleback. Washington Pass would make an excellent subject area, especially with the fresh snow I saw on the peaks on my way home. Anyone game for an overnight road trip this coming week?

And I took some photos of the

And I took some photos of the