From the inside.

In February 2005 Mike and I made our second overnight mule trip into the Grand Canyon. We went with our friends John and Lorna from Maine (Hi, Lorna!) and spent two nights at Phantom Ranch.

Although it’s not a difficult trip, it is a long one. Although Mike and I have horses and ride once in a while (not as often as we used to, I’m afraid), this is 4 to 5 hours in the saddle — enough to make anyone sore. But it’s worth it. Only a tiny percentage of the millions of people who visit the Grand Canyon each year actually descend into the canyon. This is one of the “easy” ways to do it. And you get a whole different view of the canyon once you get below the rim.

Although it’s not a difficult trip, it is a long one. Although Mike and I have horses and ride once in a while (not as often as we used to, I’m afraid), this is 4 to 5 hours in the saddle — enough to make anyone sore. But it’s worth it. Only a tiny percentage of the millions of people who visit the Grand Canyon each year actually descend into the canyon. This is one of the “easy” ways to do it. And you get a whole different view of the canyon once you get below the rim.

Phantom Ranch is nice, too. Stone cottages, Bright Angel Creek, lots of healthy hikers and campers from all over the world going through.

This photo was taken during our full day down in the Canyon. We went for a hike on a trail that climbed up from the river and made its way upriver. After the initial climb, the trail was pretty level — which is good for me because I don’t climb hills well. We saw lots of wildflowers and rock formations along the way. And a helicopter pulling equipment out from Roaring Springs on a long line.

It’s another trip I highly recommend. But book it far in advance — there’s about a 6-month waiting list. Unless you do it the way we did: go in the winter when no one wants to go.

Grand Canyon, Arizona, photo

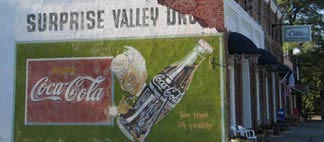

Yes, it’s the side of a building. But it’s also an old billboard for a drugstore that probably doesn’t even exist anymore. And there’s something about it that I really like.

Yes, it’s the side of a building. But it’s also an old billboard for a drugstore that probably doesn’t even exist anymore. And there’s something about it that I really like.

This dock stretches into a body of water not far from the coast. It was a haunting image, made magical by the reflections of the dock and grasses off the perfectly smooth water surface.

This dock stretches into a body of water not far from the coast. It was a haunting image, made magical by the reflections of the dock and grasses off the perfectly smooth water surface.