Another ferry flight with a pilot friend.

[Note: I’ve been working on this post for the past two weeks. Just so busy with other things! Finally got it done today. Better late than never, no? (Cynics need not answer that one.)]

For the fifth February in a row, my company, Flying M Air, has been contracted by an almond grower to provide frost protection for one of his Sacramento-area ranches. Frost protection is one of the lesser-known services a helicopter pilot can provide. We basically fly low-level up and down rows of trees to pull warm air from a thermal inversion down into the tree branches where developing crops — in this case, almonds — are growing. Almonds are susceptible to frost damage for a 4 to 8 week period starting around the time that flowers are pollinated. Because the temperatures are most likely to be lowest at night, most of the flying is done then or, more likely, right around dawn.

Before the Trip

My helicopter had been in Chandler, AZ (near Phoenix) since October when I dropped it off for its 12-year/2200 hour overhaul. Although it technically didn’t need to go in for overhaul until January 2017, I needed it done by mid-February for this work. The overhaul, which I blogged about here, takes a minimum of three months to complete, so I made sure the excellent maintenance crew at Quantum Helicopters got an early start. I don’t fly much in the winter anyway and planned to fill my downtime with some snowbirding, most of which would be in Arizona and southern California. I like snow, but not months of it, and I really do need to be in the sun in the winter time. I’ve structured my work life to give me time to go south every winter.

Director of Maintenance Paul Mansfield pulls my R44 out of the Quantum hangar after its overhaul on February 20, 2017. At that point, I hadn’t flown for four months and I was ready.

I picked up the helicopter on Monday, February 20 and spent much of the week flying it around Arizona with friends: up the Salt River, to Wickenburg, to Bisbee for an overnight trip, and to Sedona for breakfast. Along the way, I got to fly some familiar routes and see some familiar sights: along the red rock formations of Sedona, down the Hassayampa River Canyon, over the Salt River lakes, and over herds of wild horses in the Gila River bed. I needed to put some time on the helicopter to make sure there weren’t any problems before I left the area.

A lot about the helicopter felt or sounded different — and I tell you, you really get to know an aircraft when you’ve put over 2000 hours on it in 12 years. The auxiliary fuel pump sounded different, the blades sounded different, and the engine start up felt different. I immediately noticed that it was running at a higher cylinder head temperature. The guys who worked on it assured me that was normal until the rings on the newly rebuilt engine were set and I took it off mineral oil, which was recommended for the first 50 hours. The belts were also too loose when the clutch was disengaged and needed to be adjusted. And my strobe light, which had been working intermittently when I dropped it off, was now not working more often than it was. These were all minor things and I had them taken care of on Friday afternoon, when I flew it back from Wickenburg to Chandler. While I was there, the head of maintenance offered to do an oil change and, since the oil was getting dirty, I let his crew do it. I suspect the strobe light fix — which required a new part — was the most bothersome of all the fine-tuning work they did. They’d keep it in their hangar overnight.

My ride from Chandler to Mesa with Captain Woody at the controls.

While they got to work, my friend Woody picked Penny and me up in Chandler in his company’s newly leased R44 — with air conditioning, that he had turned on, likely to impress me (it worked) — and flew me to Falcon Field in Mesa, where his company is based. For some reason, I decided to live broadcast the flight via Periscope — how often do I get to be a passenger? — and Periscope decided to feature it. Soon 450+ people were watching our progress across the Chandler/Gilbert/Mesa area. By the time we’d landed, over 4,000 people had seen all or part of it. I think Woody got a kick out of that.

Woody, Jan, and Tiffani operate Canyon State Aero, a helicopter flight school that also does tours and aerial photo work. They have a modest fleet of Schweizer 300s, plus the newly added R44 and an R22 that should arrive next week. I hung around the office while they finished up paperwork and other things, occasionally answering their questions about R44s and R22s. I’m hoping to see that R44 again in Washington this summer for cherry drying.

Afterwards, Jan, Tiffani, and I went out for dinner. We tried for seafood and wound up with Chinese food. Back at their house, we talked and drank wine and watched some amazing time-lapse videos of the desert on Netflix while Penny played with their dogs and stared at their cats. I had an allergic reaction to something — likely the cats — and made the mistake of taking two Benadryl. That pretty much knocked me out for the night.

I woke up early (as usual), feeling refreshed and allergy-free. Woody showed up around 7:30 AM. After some coffee and goodbye hugs all around, Woody, Penny, and I hopped into Woody’s Prius and headed back to Chandler. We hoped to be off the ground by 9 AM.

Getting Started

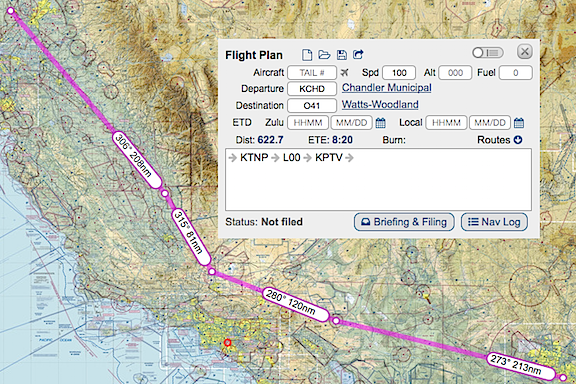

I’d planned the flight via Foreflight, with fuel stops at Twentynine Palms and Porterville, CA. The total time was estimated at about 6-1/2 hours with a slight headwind. It was a variation of a flight I’d done a few times before, starting with a solo R22 flight in the 2003 from my Wickenburg home to Placerville, CA and ending, most recently, with the 2013 trip that took my helicopter out of its Arizona hangar for the last time and brought it to California for its first frost season. This was the first time I’d be doing the route from Chandler and I worried a bit about making it all the way to Twentynine Palms for fuel. There aren’t any fuel options between Blythe and Twentynine Palms, so having almost enough fuel to get there wasn’t an option. But Foreflight and my own personal experience with the helicopter said I could do it, so that’s what I planned.

Our planned route, as shown on the SkyVector website. Good thing we didn’t fly today when I plotted that for illustration here; there’s a 22 knot headwind.

The weather was absolutely perfect for flying. I’d been monitoring various forecasts for points along our route and it all looked good with the possibility of some wind in the Tehachapi area and a slight chance of rain near our destination. Visibility was good. It would be a bit cool — even in the California desert — but the helicopter has good heat if we needed it. I was looking forward to a good, although somewhat long, flight.

Woody would fly. Woody’s an airline pilot nearing retirement. He’s got a bunch of hours in helicopters and recently got his R44 endorsement. Now he was interested in building some time in R44s. We agreed that he’d pay for fuel — which accounts for less than 1/3 of my operating costs — for the whole trip in exchange for stick time. I didn’t need the time — I have about 3500 hours in helicopters (R44, R22, 206L) — and I’d been flying around all week. And I really don’t mind being a passenger once in a while, especially with a good pilot at the controls. Still, I sat in the PIC seat and he sat in the seat beside me, using the dual controls.

Penny, of course, sat in the back. The back of the helicopter was completely full of stuff, including the wheeling toolbox I’d brought along to hold helicopter parts and accessories — think headsets, charts, log books, etc. — while the overhaul crew stripped down the helicopter to its frame, my luggage, Woody’s luggage, Woody’s pilot uniform, a box of Medifast food (long story), and Penny’s travel bag. I’d forgotten to bring along a bed for Penny, so I folded up my cotton sweatshirt and put that on top of the toolbox for her. She perched up there and slept for most of the flight.

Chandler to Twentynine Palms

I took off from Chandler, crossed the runway per the tower’s instructions, and struck out almost due west. As soon as I got to cruising altitude — 500 feet above the ground (AGL), which was 1700 feet above sea level (MSL) — I offered the controls to Woody. He took them and I settled back for the first leg of the flight.

We flew west along the south side of South Mountain, where we saw a flight of four Stearman airplanes. Woody was pretty sure he knew one of the pilots, but since we didn’t know what frequency they were on, we couldn’t raise them on the radio. (We tried 122.85, 122.75, and 123.45, which are common air-to-air frequencies around Phoenix.) I was kind of surprised to see that we were gaining on them and eventually passed them. (Did I mention that my helicopter is now about 10% faster than it was before the overhaul and now cruises easily at 110-115 knots?) We crossed the north end of the Estrella Mountains just south of Phoenix International Raceway (PIR), mostly to avoid having to talk to the tower at Goodyear. We did tune in, though, and that’s how we learned that Luke Approach was closed so we wouldn’t have to talk to them to cross Luke’s Special Air traffic Rule (SATR). Woody wasted no time getting right on course; I’d already dialed my Garmin 430 GPS in to KTNP for Twentynine Palms.

Flight of four Stearman planes, in formation.

Captain Woody flying past some mountains in California near the Colorado River.

There wasn’t much of anything exciting for the next two hours. We crossed over Buckeye Airport as another plane was coming in, flew north of the steaming cooling towers of the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant, paralleled I-10 for a while, and then drifted north of it, crossing SR60 just east of where it joined I-10. Then we crossed a little mountain range and entered the Colorado River Valley about halfway between Parker and Blythe. The Colorado River was a ribbon of blue snaking from north to south beneath us. Then we were in the southern reaches of California’s Mohave Desert, crossing a sandy desert landscape that looked as inhospitable as the Sahara but without the tall dunes. Woody kept pretty close to the GPS track, but did detour around the tallest parts of any mountains in our path. Our altitude varied from 300 to 1000 feet AGL, depending on where we were. For a good portion of the flight, we were the only living things in sight.

There’s a whole lot of nothing in the California desert between Joshua Tree National Park and the Colorado River.

I did a lot of talking, telling Woody about the helipad on top of Harquahala Mountain where I’d landed my R22 years ago and later my R44, and sharing some of the stories of my flights with low-time pilots who had done ferry flights with me over the years. We agreed that most helicopter pilots didn’t get much real-life experience as they built time as flight instructors. He asked me a bunch of questions about my time working for Papillon at the Grand Canyon. I told him about the excellent learning opportunities a season at the Canyon offered, but lamented about the fact that some of my coworkers had been either immature or cocky head cases. We talked a little about pilots we’d known who had died flying. We agreed that it was ironic that so many people said “he was a great pilot” about pilots who had died in crashes; if he was so great, why was he dead? (There are old pilots and bold pilots but no old, bold pilots.)

We flew through the very northernmost edge of Joshua Tree National Forest, along a road there. When the park fell away to the south, the abandoned buildings started up, one after the other. It was as if hundreds of people had made sad little homes on five-acre lots out there, only to abandon them to the desert wind years later. Many of them had completely blown away, leaving only concrete slabs and scattered debris. I remembered this part of the flight very clearly from my other trips through the area and didn’t take any photos this time around. But if you look on a zoomed-in satellite image of 29 Palms Highway east of Twentynine Palms, you’ll see what I’m talking about. It’s kind of eerie.

A satellite image from Google of an area east of Twentynine Palms shows a sample of the scores of abandoned or wrecked buildings out in the desert.

We reached the airport in just over two hours — which is about 15 minutes quicker than I’d planned for. (All my flight plans are for 100 knots airspeed; I’d rather over-estimate time than underestimate it, especially when flying out in the desert.) Woody landed in front of the pumps. We cooled down the engine and shut down. Woody handled the fueling while I cleaned the windows and then added a quart of oil. An old guy with a taildragger flew in and came to a stop nearby; he’d wait for us to leave before refueling. A friend of his drove into the airport and they chatted for a while. They came over to look at the helicopter and Penny, who I’d let out to get some exercise and take a pee. Woody used the bathroom and I took a picture of the helicopter. Then we all climbed back on board, I started up, and I took off to the west.

Zero-Mike-Lima at Twentynine Palms.

Twentynine Palms to Porterville

The next stop was Porterville, which was in California’s Central Valley. Unfortunately, we couldn’t fly a direct path to the Porterville because of the restricted airspace between it and Twentynine Palms. So I plotted a course that took us to Apple Valley and Victorville and on to Rosamond before climbing over the pass at Tehachapi and then dropping down into the Central Valley. The route would keep us clear of all the restricted airspace, including Edwards Air Force Base, which is east of Rosamond at the edge of a not-so-dry lake bed.

The desert west of Twentynine Palms was almost as empty as the desert east of it — but not quite. There were homes and small communities scattered about the immediate area, growing ever more rare as we continued west. After a lot of mostly empty desert, the population climbed as we passed near Lucerne and Apple Valley. Woody talked to Victorville’s tower and got permission to cross over the top — we were the only one the controller talked to the whole time we were tuned in. There were dozens of planes mothballed on the tarmac beneath us.

Some of the planes stored at Victorville.

We passed near El Mirage Lake, another dry lake bed that Woody knew from gliders or racing or something I’ve forgotten. Then more empty desert in an area the chart warned us had Unmanned Aerial System operations below 14000 feet. We tuned into Joshua Approach’s frequency as the chart suggested, but never did hear anything about drones.

Then we were south of Edwards Air Force Base and could see the huge dry lake bed where they occasionally landed the space shuttle off in the distance. But because of all the rain California had been having, it looked more wet than dry.

We turned the corner of the restricted airspace and Woody steered us northwest, over the town of Rosamond, where I had the misfortune of being stuck overnight once back in 2003, and toward the windmills on the south side of Tehachapi Pass. There had been windmills — or, more properly, wind turbines — on that hillside for as long as I could remember, but every time I came through the area, there seemed to be more. This time, I decided to share the view on Periscope. Although my voice couldn’t be heard above the sound of the helicopter’s engine and blades, I moved the camera around a lot, showing off the turbines, Woody, and even Penny perched atop the rolling toolbox in back.

The foothills of the Sierra Nevada, on the west side, just north of Tehachapi. Despite the gray day, they were very green.

We crossed over the pass and began the descent down the other side into California’s Central Valley. It was like a completely different day. On the south side of the pass, in the desert, it had been mostly sunny, bright, and warm. But on the north side, it was mostly cloudy, gray, and cool. But the foothills were so lush and green!

Our flight plan had us heading northwest bound through the valley with our next fuel stop in Porterville. As usual, I tuned in the radio for the next closest airport so we could listen in on any traffic and make a radio call if necessary. There wasn’t much to hear or report on.

When we landed at Porterville, we found a nice looking Bell 47 already parked there. We squeezed in in front of it. While Woody handled the fueling, I wiped down the windows, and Penny began exploring our surroundings, the helicopter’s owner and a friend came out. “You’re from Washington!” the helicopter’s owners — whose name I’ve already forgotten (sorry!) — exclaimed. It turns out that he reads this blog and put two and two together when he saw me. (After all, how many red R44s are piloted by a woman who often travels with a small dog?) We all chatted for a while and Woody asked for a picture of us with my helicopter. Penny made new friends, too — a pair of small dogs that hang out in the airport office. Woody and I visited the rest rooms before climbing back on board, starting up, and continuing our trip.

Woody and I posed for a photo with the helicopter at Porterville.

Porterville to Woodland

The last leg of the trip wasn’t very exciting. We flew over a lot of farmland — California’s Central Valley is a major food producer — including more than a few almond orchards in full bloom. We’d already been in the air for more than four hours and I was ready to be at the destination.

One of the many general aviation airports we passed near or over as we made our way northwest through California’s Central Valley.

One by one the small general aviation airports ticked by beneath us or within sight: Visalia, Selma, Fresno Chandler, Madera, Chowchilla, Oakdale, Lodi, Franklin.

Just past Stockton is when I began to notice the flooding below us. Farmland inundated with water. A broken levee. Closed roads. When we reached the Sacramento River and ship channel, we saw a sea of silty water with occasional “islands” of homes and equipment yards. It was sobering.

A few shots (through Plexiglas) of the flooding we flew over just south of Sacramento, CA.

Just past Davis, I asked for and took the controls. I wanted to overfly Yolo County Airport, where I was based last year. The orchard I’m contracted to cover for frost season is adjacent to it; I wanted to fly by and see the condition of the orchard and trees. There was no flooding down there — at least not that I could see — and the trees were in full bloom. Pallets of beehives were scattered among the trees. Business as usual.

I steered us north and zeroed in on our final destination, a small privately owned airport nearby where my camper was already set up and waiting for me. A while later, I was touching down at the fuel pumps, ready for Woody to top off the tanks after our long trip. Once that was done, I started it back up and hover-taxied to a parking spot on the ramp.

Then I was on to my next adventure with Woody and Penny: getting a cab to take me to where my truck was waiting, having dinner at one of my favorite restaurants in town (I highly recommend the venison osso buco), and driving Woody to Sacramento International Airport for his flight back to Arizona. I returned to the helicopter to retrieve my luggage not long after dark and, a few minutes later, was letting myself into my camper where I was soon dead asleep after the long day.

Postscript

The arrangement I had with Woody worked out for both of us, especially since fuel prices have come way down in recent months. He got more than six hours of flight time that cost him less than $500; I saved about $500 on fuel, got company for my flight, and even got treated to dinner with cocktails when we arrived at our destination. And because Woody is an airline pilot, he was able to catch a company flight back to Phoenix at no cost. Win win.

I didn’t mind letting Woody do the flying. I’d put about 10 hours on the helicopter since picking it up from overhaul and knew I’d be putting more time on it soon. Sometimes its nice to be a passenger — especially when you have confidence in the flying capabilities of the guy at the controls. (With a certain “Sunday pilot” flying, I’d rather remain on the ground.) I got to sit back, take a few photos, and enjoy the scenery.

Best of all, my helicopter is now officially back at work, earning me money — even while parked in a deluxe hangar in California.