Another helicopter outing.

I was coming into Wickenburg Municipal Airport after a tour I’d done down in Scottsdale when I spotted a helicopter sitting idle at the fuel island. Ray’s or Dave’s — I couldn’t tell from that distance. Then Dave’s voice came over the radio, announcing that he was two miles north, landing at the fuel island. Since I was headed for the same place, all three of Wickenburg’s privately owned helicopters would be at the airport at once.

“Hey, Dave. Where are you going?” I asked.

The Unicom frequency at Wickenburg was otherwise dead and local pilots aren’t shy about brief conversations over the airwaves when necessary.

“Hey, Maria. We’re going out to take a look at some slot canyons Ray found. Want to come?”

“Maybe.”

I landed on the 100LL side of the fuel island. Ray saw Dave coming in and moved the helicopter, which was parked on its dolly, so Dave could land there. Ray had his two young sons with him. A man I didn’t know was waiting at the fuel island for Dave.

I shut down as the FBO guy came out to fuel my helicopter. Soon Dave’s helicopter was sucking down JetA.

Both Dave and Ray fly Hughes 500s. Ray has a 1982 Hughes 500D utility ship and Dave has a 1969 (I think) Hughes 500C “executive” model. Both guys bought their helicopters after taking an “E-ticket” ride up the Hassayampa with Jim, who owns a 1973 Hughes 500C exec. All three of these helicopters are in excellent condition. Jim has since moved (at least temporarily) to San Diego. Dave flies his helicopter to work in Scottsdale almost every day. And Ray uses his mostly for exploring, although he’s building time so he can qualify for training with his ship’s utility hook.

I’m the poor kid on the block — at least in their eyes — with a piston helicopter. I like to remind them that I bought mine brand new.

Spur of the moment day trips like these aren’t anything unusual for Wickenburg’s helicopter pilots. What is unusual is that I should be invited. The last time they invited me on an outing, it was Ray and Jim flying their helicopters into a canyon near Burro Creek. I orbited overhead with Mike while they landed on a ridge so narrow that their skids just fit and their tailcones hung out over an abyss. “Come on down,” Jim, the guy known for trimming treetops with his main rotor blades, urged over the radio. “I don’t think so,” I replied. “Have fun.” And Mike and I headed to Prescott for lunch with pavement under my skids. Since then, Ray and Jim were convinced that I didn’t like off-airport landings. (Ah, if they only knew.) The invitations stopped. But today, I happened to be in the right place at the right time for a new invitation.

Unfortunately, I was waiting for Mike to meet me at the airport. We’d planned to wash the helicopter. Mike had taken a motorcycle ride up to Prescott to clear his mind a bit and wasn’t expected back for another 20 to 30 minutes.

Ray told me he’d overflown the place a bunch of times and had landed there with his wife recently to check it out. He said there were at least three slot canyons. One was about 6 feet wide, 100 feet deep, and 3/4 mile long. He described where the place was located in terms of landmarks: go to the Wayside Inn, then head over the north side of the lake and you’ll find it just past the first set of low mountains.

Ray probably has a GPS, but I don’t think he believes in using it. He never has coordinates for anything. But he does have the uncanny ability to re-find a place after being there just once. He’s found and returned to all kinds of things out in the desert — abandoned homesteads, waterfalls, plane wrecks, mines — you name it. If it’s out in the desert within a 50 mile radius of Wickenburg, Ray can take you there.

I know the area that Ray was describing and I know that there are lots of low mountains there. If I didn’t follow them, I wouldn’t find it. But I had to wait for Mike. They waited long enough for me to change my shirt and shoes. But when Mike still didn’t appear, they were done waiting. Dave and his friend started up first and took off with enough downwash to knock over all the extra JetA fueling equipment stored at the fuel island. He orbited the industrial park while Ray and his boys started up and warmed up. Soon they were lifting off. Then they were a pair of dark spots heading west.

Mike rolled in 10 minutes later. I told him what was up, then went to start up the helicopter while he parked his motorcycle. I managed to raise Dave on the radio and told him I’d be taking off in two minutes.

I had the Wayside Inn (home of the Hamburger in the Middle of Nowhere) programmed into my GPS, so I punched it in as a direct-to and we headed west bearing 286°. After a few moments, I heard Ray and Dave chatting on the frequency, so I told them we were airborne. They weren’t in any hurry — in fact, it seemed they were interest in overflying the remains of a trailer-based meth lab out in the desert — so I had a decent chance of catching up with them. Dave had doors off, which would slow him down and it was only Mike and I on board, so I was able to get a 115-knot cruise speed at my allowable continuous power setting of 22.5 inches of manifold pressure (30°C at 2,000 feet). I’d flown with Jim many times and he seldom topped 100 knots.

We switched frequency to 122.725 so we wouldn’t bother other pilots while we chatted. I reported our progress each time I crossed a landmark: Route 71, the unpaved Alamo Road, the Wayside Inn. When I got to the Inn, they were already across the lake. Fortunately, Ray had to poke around a bit to find a good landing zone. I reached the west side of the lake just as Dave set down on a ridge. I didn’t see either of them — at least at first. Then I caught sight of a flash of light: A strobe about 2 miles away.

“I have you in sight,” Dave said at almost the same moment. “I’m at your one o’clock.”

That’s where I saw the strobe. I homed in on it.

Ray was still listening in as he cooled down his engine. “There’s a good landing zone right behind me,” he said. “I can guide you in if you want.”

I circled around Dave’s helicopter, which was still spinning up on the ridge. Ray was on a low arm of the mountain. The slot canyon was just to the left of his helicopter. There was plenty of room behind him — even for a helicopter 38-1/2 feet long — between palo verde trees, cactus, and shrubs.

“I got it,” I told him. I made my approach and set down in the longest clear area I could find. The top branches of a palo verde tree on my left were about a foot beneath my unloaded spinning blades.

I cooled off my engine, which had been running hotter than usual during our high speed pursuit (summer is almost here in Arizona), and shut down. The blades were just coasting to a stop on their own when Dave and his friend reached us. Ray and his boys were waiting patiently for us.

We didn’t waste any time scrambling down the side of the steep canyon wall just 10 feet from Ray’s helicopter. I was wearing Keds, which were the only shoes I had at the airport (other than my loafers) and they didn’t offer any traction at all. I had to do the last little bit on my butt. Then we were in at the mouth of a narrow canyon that cut into the rock wall in front of us.

Ray led the way, followed closely by his boys. “Keep an eye out for snakes,” he warned.

We slipped into the canyon. The rock walls were a conglomeration of rocks laid down when Arizona was under water. You could see where different layers of rock had been deposited in the sand of a sea bed, cemented there by pressure and time. The sea receded, leaving Arizona dry with many flat valleys between mountain ranges. Over thousands (if not millions?) of years, water had cut through this particular piece of rock, digging deeper with every storm. The slot canyon was narrow — even narrower than Antelope Canyon — but the walls were rough, lined with the rocks that had been deposited there millions of years ago.

The canyon twisted and turned on a gentle downward slope, with an occasional drop of 2 to 4 feet where we had to scramble over boulder deposits. Inside, the air was cooler and, as the walls climbed on either side of us, cooler breezes blew past us. Sunlight didn’t get to the canyon floor this time of year, so the rock walls hadn’t heated. A side canyon entered suddenly from the left with a natural bridge of rock over it. As we continued down, a few other steep canyons joined in less dramatically. Then the canyon opened abruptly to a much wider canyon with steep walls and tire tracks on its sandy floor.

The canyon twisted and turned on a gentle downward slope, with an occasional drop of 2 to 4 feet where we had to scramble over boulder deposits. Inside, the air was cooler and, as the walls climbed on either side of us, cooler breezes blew past us. Sunlight didn’t get to the canyon floor this time of year, so the rock walls hadn’t heated. A side canyon entered suddenly from the left with a natural bridge of rock over it. As we continued down, a few other steep canyons joined in less dramatically. Then the canyon opened abruptly to a much wider canyon with steep walls and tire tracks on its sandy floor.

We all agreed that the canyon had been pretty cool. Ray led the way to the next one, which was a few hundred yards downstream in the big canyon. We walked up the canyon, but it was much shorter and ended with a 15-foot vertical wall. We retraced our footsteps out to the main canyon.

“There’s another one about a quarter mile away,” Ray told us. “Want to see that, too?”

We did, so we started walking. I think Ray’s estimation of distance was a little off. It had to be at least a half mile. The sun was still shining into the wide canyon, and it was warm. I’m out of shape and didn’t walk easily on the sandy canyon floor. But after passing a much narrower canyon that one of the boys explored on his own, we finally reached the third slot canyon. Like the others, it cut through the solid conglomeration of rocks with cool breezes along the way. And like the first canyon, it was long, stretching back into the mountain as it climbed. Mike and I and one of Ray’s boys went quite a distance, hoping we’d be able to climb out and see where the helicopters were parked. But it soon became apparent that we’d have at least a mile hike ahead of us — and we still might not see them. None of us wanted to walk that far, so we went back.

We did, so we started walking. I think Ray’s estimation of distance was a little off. It had to be at least a half mile. The sun was still shining into the wide canyon, and it was warm. I’m out of shape and didn’t walk easily on the sandy canyon floor. But after passing a much narrower canyon that one of the boys explored on his own, we finally reached the third slot canyon. Like the others, it cut through the solid conglomeration of rocks with cool breezes along the way. And like the first canyon, it was long, stretching back into the mountain as it climbed. Mike and I and one of Ray’s boys went quite a distance, hoping we’d be able to climb out and see where the helicopters were parked. But it soon became apparent that we’d have at least a mile hike ahead of us — and we still might not see them. None of us wanted to walk that far, so we went back.

We retraced our steps back to the first canyon, chatting about all kinds of things on the way. Ray and Dave continued walking past its mouth, which was hidden behind a large palo verde tree. I don’t know if they really didn’t see it or if they were trying to fool us into walking past it. I wasn’t being fooled — at least not by that ploy. They had plenty of other gags to fool me with — Ray has a real talent for delivering pure bull with a straight face and Dave is the perfect straight man: normally trustworthy so you always believe what he says. (I know better now.)

Back at the helicopters, we went straight for our cooler bag with its supply of water, Gatorade, cheese, and salami. We re-hydrated and snacked. Dave and his friend had to walk all the way back up the ridge to get their drinks and they didn’t come back. When we heard Dave start his engine, we knew it was time to leave.

Back at the helicopters, we went straight for our cooler bag with its supply of water, Gatorade, cheese, and salami. We re-hydrated and snacked. Dave and his friend had to walk all the way back up the ridge to get their drinks and they didn’t come back. When we heard Dave start his engine, we knew it was time to leave.

I was just climbing into my helicopter when Dave took off and zoomed past us. Ray and I were ready to go at the same time. (It’s good helicopter outing etiquette to make sure no helicopter is left behind and Ray and I were watching out for each other.) Ray left first, popping off the ground like a champagne cork. I tried to be a bit more graceful but didn’t do much better. I followed the slot canyon — a narrow crack in the rock — down to the main canyon as I climbed. Ray was at my four o’clock. Dave was completely out of sight.

Jim might be slow, but Ray isn’t. He and I were flying neck and neck as we crossed the lake, but he inched his way past me as we climbed the flat valley east toward Wickenburg. By the Wayside Inn, he was a half mile ahead of me. He’d beat me back to Wickenburg by at least 3 minutes; the only reason it was that short a time was that I took a more direct route back, following my GPS’s advice. Dave had let his passenger off at the airport and was just getting ready to leave when I came in. He took off and I set down.

The sun was just setting.

It had been a nice little outing, one I really needed to do. Lately, the only time I fly is to take paying passengers on tours and charters or to go to or from a passenger pickup point. I’ve flown down to the Phoenix area so many times the past few months. After a while, it just isn’t fun. But outings like this — with friends in remote places, seeing cool things — is a better reason to fly. Even if someone else isn’t picking up the tab.

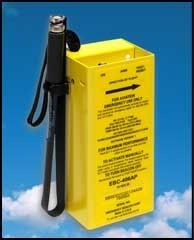

An ELT is a piece of equipment you hope you never need, but one you pray is working right when you do need it.

An ELT is a piece of equipment you hope you never need, but one you pray is working right when you do need it. The canyon twisted and turned on a gentle downward slope, with an occasional drop of 2 to 4 feet where we had to scramble over boulder deposits. Inside, the air was cooler and, as the walls climbed on either side of us, cooler breezes blew past us. Sunlight didn’t get to the canyon floor this time of year, so the rock walls hadn’t heated. A side canyon entered suddenly from the left with a natural bridge of rock over it. As we continued down, a few other steep canyons joined in less dramatically. Then the canyon opened abruptly to a much wider canyon with steep walls and tire tracks on its sandy floor.

The canyon twisted and turned on a gentle downward slope, with an occasional drop of 2 to 4 feet where we had to scramble over boulder deposits. Inside, the air was cooler and, as the walls climbed on either side of us, cooler breezes blew past us. Sunlight didn’t get to the canyon floor this time of year, so the rock walls hadn’t heated. A side canyon entered suddenly from the left with a natural bridge of rock over it. As we continued down, a few other steep canyons joined in less dramatically. Then the canyon opened abruptly to a much wider canyon with steep walls and tire tracks on its sandy floor. We did, so we started walking. I think Ray’s estimation of distance was a little off. It had to be at least a half mile. The sun was still shining into the wide canyon, and it was warm. I’m out of shape and didn’t walk easily on the sandy canyon floor. But after passing a much narrower canyon that one of the boys explored on his own, we finally reached the third slot canyon. Like the others, it cut through the solid conglomeration of rocks with cool breezes along the way. And like the first canyon, it was long, stretching back into the mountain as it climbed. Mike and I and one of Ray’s boys went quite a distance, hoping we’d be able to climb out and see where the helicopters were parked. But it soon became apparent that we’d have at least a mile hike ahead of us — and we still might not see them. None of us wanted to walk that far, so we went back.

We did, so we started walking. I think Ray’s estimation of distance was a little off. It had to be at least a half mile. The sun was still shining into the wide canyon, and it was warm. I’m out of shape and didn’t walk easily on the sandy canyon floor. But after passing a much narrower canyon that one of the boys explored on his own, we finally reached the third slot canyon. Like the others, it cut through the solid conglomeration of rocks with cool breezes along the way. And like the first canyon, it was long, stretching back into the mountain as it climbed. Mike and I and one of Ray’s boys went quite a distance, hoping we’d be able to climb out and see where the helicopters were parked. But it soon became apparent that we’d have at least a mile hike ahead of us — and we still might not see them. None of us wanted to walk that far, so we went back. Back at the helicopters, we went straight for our cooler bag with its supply of water, Gatorade, cheese, and salami. We re-hydrated and snacked. Dave and his friend had to walk all the way back up the ridge to get their drinks and they didn’t come back. When we heard Dave start his engine, we knew it was time to leave.

Back at the helicopters, we went straight for our cooler bag with its supply of water, Gatorade, cheese, and salami. We re-hydrated and snacked. Dave and his friend had to walk all the way back up the ridge to get their drinks and they didn’t come back. When we heard Dave start his engine, we knew it was time to leave.