There’s no real reason for it.

A Twitter/Google+ friend of mine, Chris, linked to an article on the New York Times website today, “Fliers Still Must Turn Off Devices, but It’s Not Clear Why.” His comment on Google+ pretty much echoed my sentiments:

I do all my book reading on an iPad, and it’s annoying that I can’t read during the beginning and end of a flight, likely for no legitimate reason.

This blog post takes a logical look at the practice and the regulations behind it.

What the FAA Says

In most instances, when an airline flight crew tells you to turn off portable electronic devices — usually on takeoff and landing — they make a reference to FAA regulations. But exactly what are the regulations?

Fortunately, we can read them for ourselves. Indeed, the Times article links to the actual Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) governing portable electronic devices on aircraft, 121.306. Here it is in its entirety:

121.306 Portable electronic devices.

(a) Except as provided in paragraph (b) of this section, no person may operate, nor may any operator or pilot in command of an aircraft allow the operation of, any portable electronic device on any U.S.-registered civil aircraft operating under this part.

(b) Paragraph (a) of this section does not apply to—

(1) Portable voice recorders;

(2) Hearing aids;

(3) Heart pacemakers;

(4) Electric shavers; or

(5) Any other portable electronic device that the part 119 certificate holder has determined will not cause interference with the navigation or communication system of the aircraft on which it is to be used.

(c) The determination required by paragraph (b)(5) of this section shall be made by that part 119 certificate holder operating the particular device to be used.

So what this is saying is that you can’t operate any portable electronic device that the aircraft operator — the airline, in this case — says you can’t. (Read carefully; a is the rule and b is the loophole.) You can, however, always operate portable voice recorders, hearing aids, heart pacemakers (good thing!), and electric shavers (?).

So is the FAA saying you can’t operate an iPad (or any other electronic device) on a flight? No. It’s the airline that says you can’t.

Interference with Navigation or Communication Systems

In reading this carefully, you might assume that the airline has determined that devices such as an iPad may cause interference with navigation or communication systems. After all, that’s the only reason the FAA offers them the authority to require these devices to be powered down.

But as the Times piece points out, a 2006 study by the Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics found no evidence that these devices can or can’t interfere. Sounds to me like someone was avoiding responsibility for making a decision.

In the meantime, many portable electronic devices, including iPads, Kindles, and smart phones have “airplane mode” settings that prevent them from sending or receiving radio signals. If this is truly the case, it should be impossible for these devices to interfere with navigation or communication systems when in airplane mode. And if all you want to do with your device is read a downloaded book or play with an app that doesn’t require Internet access, there should be no reason why you couldn’t do so.

And can someone really make the argument that an electronic device in airplane mode emits more radio interference than a pacemaker or electric shaver?

And what about the airlines that now offer wi-fi connectivity during the flight? You can’t have your device in airplane mode to take advantage of that service. Surely that says something about the possibility of radio interference: there is none. Evidently, if you’re paying the airline to use their wi-fi, it’s okay.

What’s So Special about Takeoff and Landing?

Of course, since you are allowed to use these devices during the cruise portion of the flight, that begs the question: What’s so special about takeoff and landing?

As a pilot, I can assure you that the pilot’s workload is heavier during the takeoff and landing portions of the flight. There’s more precise flying involved as well as more communication with air traffic control (ATC) and a greater need to watch out for and avoid other aircraft.

But in an airliner, the pilots are locked in the cockpit up front, with very little possibility of distractions from the plane full of seat-belted passengers behind them — even if some of them are busy reading the latest suspense thriller or playing an intense game of Angry Birds.

Are the aircraft’s electronics working harder? I don’t think so.

Are they more susceptible to interference? I can’t see how they could be.

So unless I’m wrong on any of these points, I can’t see why the airlines claim that, for safety reasons, these devices need to be powered off during takeoff and landing.

It’s a Control Issue

I have my own theory on why airlines force you to power down your devices during takeoff and landing: They don’t want their flight attendants competing with electronic devices for your attention.

By telling you to stow all this stuff, there’s less of a chance of you missing an important announcement or instruction. Theoretically, if the aircraft encountered a problem and they needed to instruct passengers on what they should do, they might find it easier to get and keep your attention if you weren’t reading an ebook or listening to your iPod or playing Angry Birds. Theoretically. But there are two arguments against this, too:

- You can get just as absorbed in a printed book (or maybe even that damn SkyMall catalog) as you could in an ebook.

- If something were amiss, the actual flight/landing conditions and/or other screaming/praying/seatback-jumping passengers would likely get your attention.

But let’s face it: airlines want to boss you around. They want to make sure you follow their rules. So they play the “safety” card. They tell you their policies are for your safety. And they they throw around phrases like “FAA Regulations” to make it all seem like they’re just following someone else’s rules. But as we’ve seen, they have the authority to make the rule, so it all comes back to them.

And that’s the way they like it.

How Cell Phones Fit Into This Discussion

Cell phone use is a completely different issue. In the U.S., it isn’t the FAA that prohibits cell phone use on airborne aircraft — it’s the FCC. You can find the complete rule on that in FCC regulation 22.925, which states (in part):

22.925 Prohibition on airborne operation of cellular telephones.

Cellular telephones installed in or carried aboard airplanes, balloons or any other type of aircraft must not be operated while such aircraft are airborne (not touching the ground). When any aircraft leaves the ground, all cellular telephones on board that aircraft must be turned off.

There are reasons for this, but an analysis of whether or not they’re valid is beyond the scope of this discussion.

I just want to be able to read books on my iPad from the moment I settle into my airliner seat to the moment I leave it.

I was so appreciative that when I heard about the event and the fact that a few aircraft would be on static display, I offered to put my helicopter on display. So yesterday morning, at 8:15 AM, I parked on the ramp in front of the terminal building to give attendees just one more aircraft to look at. I even hung out for a while and let kids climb into my seat.

I was so appreciative that when I heard about the event and the fact that a few aircraft would be on static display, I offered to put my helicopter on display. So yesterday morning, at 8:15 AM, I parked on the ramp in front of the terminal building to give attendees just one more aircraft to look at. I even hung out for a while and let kids climb into my seat. There were other organizations on hand, with tables set up under a big shade. The

There were other organizations on hand, with tables set up under a big shade. The  Of course, the iPad version (shown here with a screen shot of all my 2010 activity) syncs with the Mac version, so I can log time on the go and sync it all up when I get back to my office. Or I can pull old log entries out of my paper logbook and enter them in my Mac and then sync it all to my iPad.

Of course, the iPad version (shown here with a screen shot of all my 2010 activity) syncs with the Mac version, so I can log time on the go and sync it all up when I get back to my office. Or I can pull old log entries out of my paper logbook and enter them in my Mac and then sync it all to my iPad. Who I’m talking to: Deer Valley Tower

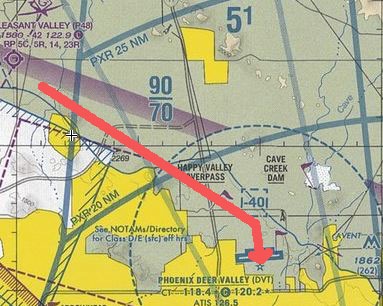

Who I’m talking to: Deer Valley Tower In the Phoenix area, there’s less than a mile between the Deer Valley class D airspace and the Scottsdale class D airspace. The towers know this, of course, so if you’re flying from one to the other, they usually give you a frequency change when you’re less than three miles from the airport you’re leaving. Even if you didn’t ask for it, they’ll say something like:

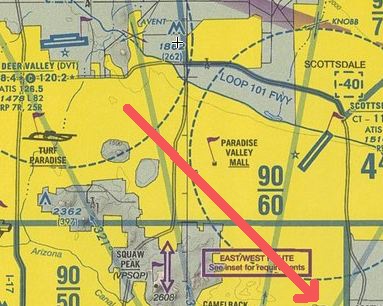

In the Phoenix area, there’s less than a mile between the Deer Valley class D airspace and the Scottsdale class D airspace. The towers know this, of course, so if you’re flying from one to the other, they usually give you a frequency change when you’re less than three miles from the airport you’re leaving. Even if you didn’t ask for it, they’ll say something like: Who I’m talking to: Scottsdale Tower

Who I’m talking to: Scottsdale Tower