Not as bad as it seems.

As I type this, I’m sitting on a leather sofa in the second floor “pilot lounge” area of a friend’s hangar. The hangar is at a San Diego-area airport and the three large windows on this side of the room face out over one of the airport’s three runways. Outside it’s dark. From undefined glow of the lights across the runway that fade into the darkness, I can tell that it’s foggy. I can barely see the sweep of the white and green rotating beacon atop the control tower on the other side of the runway.

It’s 5 AM local time. I get up early no matter where I am.

If I look down out the closest window to the pavement outside the hangar, I can see my helicopter. I tied down the blades — needlessly, it appears; there doesn’t seem to be any wind here — and pushed it over to a level spot on the ramp area, clear of the taxiway. Seems weird to have it parked there, but it’s been there two nights now and no one has bugged me about it. After all, other folks park cars and other vehicles in the same place at the end of their hangars.

In looking at that fog, I’m sure I’ll be wiping the helicopter down with a towel later today. You get spoiled living in the desert.

You might wonder why I don’t put the helicopter in the hangar I’m camped out above. I could. But there’s already a Hughes 500c helicopter, a Diamondstar airplane, Jaguar sedan, and a GT40 sports car in there. There’s still a big empty space where the hangar’s third aircraft occupant usually parks his Twinstar and I probably could have fit in that space. But it didn’t seem worth the bother. A few days out on the sun won’t kill my helicopter. But with this salt-laden fog coming in, I’ll definitely be washing down the helicopter before I put it away at home later on today.

It’s wonderfully quiet here, with just some white noise — a distant hum that could be someone’s heat pump or even a generator. The heat inside the lounge, which just went on, is a lot noisier. The space I’m in takes up half the depth and the full width of the hangar below me. It’s completely enclosed and insulated, finished with nice plaster walls and carpeting. There are windows that open with screens on all four sides of the space; on one side, they open into the hangar’s main area.

There are three rooms up here, including a full bathroom, and one of the rooms has a little kitchen area, with certain conveniences conspicuously missing. There’s no stove or oven or dishwasher, but there’s a double sink and microwave and the small refrigerator has an ice maker in it. There isn’t much in the way of food in the cabinets other than coffee and the non-perishable condiments that go with it. But there’s a Starbucks off-airport, walking distance away, and I know the owner of this hangar frequently drives across the runway in his well-equiped golf cart to get his meals at the airport restaurant.

In all honestly, the second floor of this hangar is very museum-like. My friends collect Mexican, South American, and Native American art. Although their best and most valuable pieces are in their two other homes, there’s a lot of it here. There’s also a lot of weird items you’d expect to find in a museum: a copper diving mask, pull-down wall maps dating from the 1950s and 1960s, a fully restored glass-tanked fuel pump, an old Coke machine that takes dimes (with a small bowl of dimes on top and bottles of Corona beer inside), two free-standing and fully restored wood popcorn machines — the list goes on and on. Sometimes it’s neat just to look at these things. But when you pop a dime into the Coke machine and pull out a Corona, you remember that all of these things are still fully functional.

I’d take a picture and include it here, but I really think that would be a serious invasion of my friend’s privacy.

My friend is not here, although his helicopter is. He used to spend a lot of time here when the place was first built. He and his wife had lived in Wickenburg before then. His wife fell out of love with the town when the Good Old Boy bullshit that makes Wickenburg what it is started directly affecting her. From that point on, it was just weeks before she was desperate to get out of town and continue life elsewhere. She started spending more and more time in California with her daughter and less and less time at home with her husband. The hangar was a temporary solution, followed by an apartment on the coast and then a condo in Beverly Hills with a second apartment in Las Vegas. They spend most of their time in those places now, although my friend uses the hangar as a kind of getaway place when he has a few days off and wants to go flying. They still own their home in Wickenburg and have tried three Realtors in the past two years to sell it. But there isn’t much demand for a $1 million home in Wickenburg these days, even when it has a separate guest house, hangar and helipad, horse setup and plenty of acreage around it for privacy.

They want us to buy it, of course, but I’m not prepared to go into debt to buy a home and I’m certainly not going to sink myself any deeper into Wickenburg.

Mike and I have been camping out here in the hangar for a few days. Supposedly, it’s against federal regulations to live on the property of a Federally-funded airport — which is why this “pilot lounge” is missing a few necessities of life, like a bed. So we’re sleeping on an air mattress. We’re not living here, of course. Just sleeping over. We have business in the area during the say and just needed a cheap place to spend the night. My friend was kind enough to let us camp out here.

It’s a wonderful place to hang out. This airport, unlike a few I could name, has a lively population of tenants in the hangars. When I went out for coffee yesterday morning, I walked by a hangar where a man was busy preflighting a Cessna in preparation for an early morning flight. He greeted me as if he knew me and we shared pleasantries about the weather: “Great day to fly.” “Sure is.”

After lunch, we decided to drop by the hangar to put our leftovers in the fridge. We were very surprised to find our big hangar door wide open. Inside, tending to the Diamondstar, were three Brits. We introduced ourselves by name and were immediately offered coffee. It later came out that we were friends of the hangar’s owner. “Oh, well then you must come by at 5 for cocktails,” the woman said. “We have such fun.” When I mentioned I was in the area working on a video project, she hurriedly took me to meet a man named Steve who is also in film. He was stretched out on a leather sofa in his modest hangar, watching a game on a big television. The TV’s rabbit ears antenna was out of the pavement beside a gas BBQ grill. Inside the hangar was the neatest and cleanest Cessna 140 that I’d ever seen.

Later, when we returned — too late for cocktails, I’m sorry to say; I could have used one — we were treated to stories of other dinner parties in the hangar’s big lower area, with unknown pilots stopping by to join in the fun. There’s a real sense of community here. It’s more than just a place to store your aircraft. It’s a place to hang out and meet people with similar interests. It’s a place to watch the world — and the planes — go by.

It’s nearly 6 AM now and I can see a tiny bit of light in the sky. The fog is still thick on the runway; the rotating beacon is now invisible. If the tower controller have come on duty, there’s not much for them to do. It’s IFC — Instrument Meteorological Conditions — here and I’d be very, very surprised if we saw or heard a plane outside until the fog lifted. But I’ll get dressed and make a run for coffee. We have more work to do today. Then, at about noon, we’ll start the 2-1/2 hour flight back to Wickenburg.

I’m looking forward to camping out here again.

The first point isn’t even on the lake. Horseshoe Bend (A) is a horseshoe-shaped curve in the river a few miles downstream from the dam. It’s often photographed from the viewpoint at the outside “top” of the bend, which you can walk to from a parking area right off Route 89. Here’s a photo I took today from the overlook.

The first point isn’t even on the lake. Horseshoe Bend (A) is a horseshoe-shaped curve in the river a few miles downstream from the dam. It’s often photographed from the viewpoint at the outside “top” of the bend, which you can walk to from a parking area right off Route 89. Here’s a photo I took today from the overlook. The Glen Canyon Dam (B) is the dam that keeps all the water in the lake. It’s accompanied by a bridge a few hundred feet downstream that crosses Glen Canyon. From the air, you can get good views of both.

The Glen Canyon Dam (B) is the dam that keeps all the water in the lake. It’s accompanied by a bridge a few hundred feet downstream that crosses Glen Canyon. From the air, you can get good views of both.

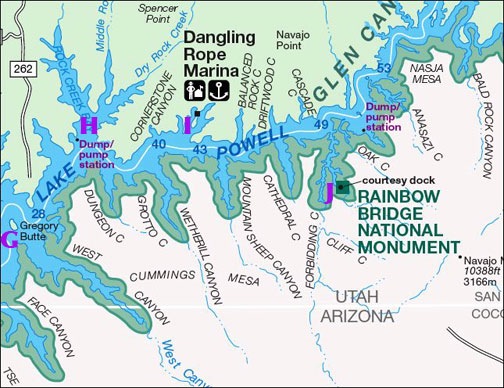

Gregory Butte (G) stands out in my mind primarily because of its photogenic qualities. If you’re flying uplake early in the day and take a photo up Last Chance Canyon with Gregory Butte in the foreground…well, you get the photo you see here. It’s one of my favorite views of the lake. This shot was taken by my husband on one of our first helicopter trips to the lake together. The water level is a bit higher right now. If it rises some more, Gregory will become an island.

Gregory Butte (G) stands out in my mind primarily because of its photogenic qualities. If you’re flying uplake early in the day and take a photo up Last Chance Canyon with Gregory Butte in the foreground…well, you get the photo you see here. It’s one of my favorite views of the lake. This shot was taken by my husband on one of our first helicopter trips to the lake together. The water level is a bit higher right now. If it rises some more, Gregory will become an island.

Everyone wants to see Rainbow Bridge (J) from the air. Everyone, that is, except those who know better.

Everyone wants to see Rainbow Bridge (J) from the air. Everyone, that is, except those who know better. like the time I was flying orbits around Horseshoe Bend when a line of 9 tour planes flew past “The Shoe” 2,500 feet below me. Sure, there was plenty of separation, but only because I heard them coming and stayed clear. The photo you see here was taken during that flight by photographer

like the time I was flying orbits around Horseshoe Bend when a line of 9 tour planes flew past “The Shoe” 2,500 feet below me. Sure, there was plenty of separation, but only because I heard them coming and stayed clear. The photo you see here was taken during that flight by photographer

Lake Powell is outrageously beautiful. Its clear, blue water reflects the clear Arizona/Utah sky. Its red rock canyons, buttes, and other formations change throughout the day with the light. Deep, narrow canyons cut into the desert, making mysterious pathways for boaters to explore. When the wind and water is calm, the buttes and canyon walls cast their reflections down on the water. In the rare instances when weather moves in, low clouds add yet another dimension to the scenery.

Lake Powell is outrageously beautiful. Its clear, blue water reflects the clear Arizona/Utah sky. Its red rock canyons, buttes, and other formations change throughout the day with the light. Deep, narrow canyons cut into the desert, making mysterious pathways for boaters to explore. When the wind and water is calm, the buttes and canyon walls cast their reflections down on the water. In the rare instances when weather moves in, low clouds add yet another dimension to the scenery. Sure, it’s wonderful by boat — especially by houseboat over 5 to 7 days with a bunch of good friends or family members — but views are limited from the ground and distances take a long time to cover. Let’s face it: the lake’s surface area is 266 square miles (at full pool) and it stretches 186 miles up the Colorado and San Juan Rivers. You could explore the lake by boat for a year and not get a chance to visit each of its 90 water-filled side canyons.

Sure, it’s wonderful by boat — especially by houseboat over 5 to 7 days with a bunch of good friends or family members — but views are limited from the ground and distances take a long time to cover. Let’s face it: the lake’s surface area is 266 square miles (at full pool) and it stretches 186 miles up the Colorado and San Juan Rivers. You could explore the lake by boat for a year and not get a chance to visit each of its 90 water-filled side canyons.

Most people fly into Page, since it’s the only airport near a town. If you come in from the northwest and land on Runway 15, as we are in this photo — well, we’re actually lined up for landing on the taxiway — you’ll make your descent right over the lake, west of Antelope Marina. (The town is all that green stuff to the right.) Taking off on Runway 33 has you shooting out over the edge of the mesa and lake. Pretty dramatic stuff. I have a lot of fun with it since I don’t really “climb out” after takeoff. The airport is at 4316 feet and the lake is currently at 3629 feet, so there’s no reason to gain altitude if I’m just cruising the lake.

Most people fly into Page, since it’s the only airport near a town. If you come in from the northwest and land on Runway 15, as we are in this photo — well, we’re actually lined up for landing on the taxiway — you’ll make your descent right over the lake, west of Antelope Marina. (The town is all that green stuff to the right.) Taking off on Runway 33 has you shooting out over the edge of the mesa and lake. Pretty dramatic stuff. I have a lot of fun with it since I don’t really “climb out” after takeoff. The airport is at 4316 feet and the lake is currently at 3629 feet, so there’s no reason to gain altitude if I’m just cruising the lake.

So I took the controls, bought everything back up to 102% RPM, and started raising the collective. I’ve done a lot of flying in high density altitude situations, so I know from experience that it takes a certain “touch” to avoid low rotor situations. I pulled the collective up slowly, felt the helicopter get light on its skids, and kept pulling. We were off the ground at 22 inches of manifold pressure, in a nice, steady hover. The engine sounded good, the low rotor RPM horn kept quiet. Keeping in mind that it takes more power to hover than to fly, I was satisfied that I’d be able to take off at our current weight and density altitude situation. I set it back down and we shut down.

So I took the controls, bought everything back up to 102% RPM, and started raising the collective. I’ve done a lot of flying in high density altitude situations, so I know from experience that it takes a certain “touch” to avoid low rotor situations. I pulled the collective up slowly, felt the helicopter get light on its skids, and kept pulling. We were off the ground at 22 inches of manifold pressure, in a nice, steady hover. The engine sounded good, the low rotor RPM horn kept quiet. Keeping in mind that it takes more power to hover than to fly, I was satisfied that I’d be able to take off at our current weight and density altitude situation. I set it back down and we shut down. I’d wanted to depart into the wind, using the 6 to 8 mph breeze to help me get through effective translational lift (ETL), which occurs around 24 knot airspeed in an R44. The trouble was, the wind was blowing across the ramp area and a small jet was parked at the edge of the ramp, making a low-level obstruction there. If I hover-taxied over to the taxiway, I could takeoff downhill, but with a quartering tailwind that would not help the situation. Of course, a running takeoff — that’s where you get the helicopter light on its skids and run on the skid shoes until you’re through ETL — would be possible on the taxiway, which was smooth. In the end, I decided to pick it up into a hover and take off with a quartering headwind toward the runway and big empty space beyond its approach end. I’d have pavement under me for at least 200 feet, so I could always slide along it or abort the takeoff with a running landing if I couldn’t get enough lift to clear the fence and the road beyond it. You can see all this in the diagram; we were the red X.

I’d wanted to depart into the wind, using the 6 to 8 mph breeze to help me get through effective translational lift (ETL), which occurs around 24 knot airspeed in an R44. The trouble was, the wind was blowing across the ramp area and a small jet was parked at the edge of the ramp, making a low-level obstruction there. If I hover-taxied over to the taxiway, I could takeoff downhill, but with a quartering tailwind that would not help the situation. Of course, a running takeoff — that’s where you get the helicopter light on its skids and run on the skid shoes until you’re through ETL — would be possible on the taxiway, which was smooth. In the end, I decided to pick it up into a hover and take off with a quartering headwind toward the runway and big empty space beyond its approach end. I’d have pavement under me for at least 200 feet, so I could always slide along it or abort the takeoff with a running landing if I couldn’t get enough lift to clear the fence and the road beyond it. You can see all this in the diagram; we were the red X.