What a rush!

My Lake Havasu job on Friday turned out to be two jobs.

I’d been hired by a man based in Oregon who had designed and built a totally custom, stainless steel speedboat. His company, Liquid Technologies, had brought the boat down to Havasu to participate in a big boating event there. It was the second time the boat was in the water and he wanted to get video of the boat out on the lake. He’d hired Todd from Joker’s Wild Promotions to do the camera work.

Todd met me at the airport at 8 AM on Friday. He decided to sit behind me in the helicopter, so we’d both have pretty much the same view. We took just that door off. It was still cool and the last thing I needed was to catch a cold. Then we put on our life jackets and climbed on board.

Todd told me the game plan as I warmed the engine. The boat would be at the cove at the Nautical Inn, just southwest of London Bridge. We’d go there and circle it as it backed out, then follow it slowly through the no wake zone to the open lake. Then the boat would cruise at about 50 knots and we’d fly with it.

He asked how low I could fly. I told him I didn’t know — I hadn’t flown with a boat before. He told me to stick with my comfort level. No problem there — I’d never do anything I wasn’t comfortable with.

We took off and got to the cove within minutes. The boat was about 45 feet long and silver, looking very sleek. It was surrounded by literally dozens of similar boats, most of which had bright paint jobs, just parked along the cove. We circled the cove three times as it backed out, getting lower with each pass. Then we followed it.

The day was perfect for flying. Little or no wind, still cool and comfortable. The lake water was almost mirror smooth. Zero-Mike-Lima seemed to have all the power in the world with just two of us on board, even with close to full tanks of fuel.

The boat had four men in it, each wearing life jackets and headsets. They did their absolute best not to look at us. That turned out to be a pain in the neck later on, when Todd wanted them to speed up and they never saw his hand signals. We followed them down the lake at a good clip and I got closer and lower in gradual steps. After a while, I was about 15 to 20 feet off the top of the lake, 30 feet from the boat, cruising along beside it at 50 to 60 knots.

Todd gave me instructions to position us in relation to the boat. In front, looking back. Behind, looking forward. Above, looking down. Low, looking straight on. I followed his instructions, keeping an eye on the boat and on the lake in front of me. There were only a few boats out there and I didn’t want to overfly any of them at low level, so once or twice I had to shift position to dodge around another boat.

What’s interesting to me about all this is that I didn’t have to give the flying much thought. Both hands and feet just did what they needed to do to get the helicopter where I wanted it to be. I’d expected the work to be challenging and to require a lot of concentration to do. But it wasn’t that difficult at all. I think it’s because of the flying conditions — which were so darn easy — and the power available to me. There’s no way I could have done the job as easily in an R22 with its limited power and two good-sized people on board.

We got down to the pumping station for one of the two reservoirs near the Parker Dam and I saw an unpleasant sight: high tension power line towers. “I think there are wires ahead,” I said to Todd.

“Oh, yeah,” he said. “I forgot to tell you about them.”

Great. “Well, I want to stop before we get to them,” I said.

He assured me that that’s as far as they’d go. I stopped over the water, climbed up a bit, and went into a slow circle about a half mile upriver from the wires. The boat kept going, then turned around and came back to us. Then we started up again, now going upriver. We started getting fancy, coming up behind the boat, passing it, and flying around its front end as it sped by us. A maneuver very similar to one I’d done at a carmaker’s test track for a film crew months before. Todd was very pleased.

We got back to town and they boat turned around again. Todd switched to still photos. He had a professional Canon camera capable of 6 shots per second at 8 megapixels. We followed the boat about 1/4 back down the lake. It turned and came back. More still photos, more video.

Then we were done. We headed back to the airport. The 1.2 hours of Hobbs time had gone quickly.

I asked Todd how I’d done. He said that I was now his current favorite pilot. Unfortunately, he doesn’t want to pay my ferry costs from Wickenburg (1.6 hours round trip), so I don’t know how much work he’ll give me in the future.

We shut down and I closed up the ship. Then we went into town, where he dropped off the video and still photos at his office. One of the guys who works with him, Larry, wasted no time feeding the video into a computer. I got to see some of it. The beginning wasn’t too impressive as I warmed to the task and Todd got used to a new video camera. But then there were a bunch of great sequences. He had over 45 minutes of raw video to go into a 10-minute final video. The still photos were even better. I got to see them on Todd’s computer. He promised to send me a few; maybe I’ll get to show one or more of them off here.

Larry dropped me off at the Nautical Inn, where I met with the client and presented my bill. He was a nice man, excited about the sport and his new boat. He paid me with a check and I left them to find my next client.

Todd had gotten me hooked up with the guys from Extreme Boats magazine. They wanted to get photos of some of the other speedboats as they went downlake for a “lunch run.” So I met with Casey, the magazine publisher, and hitched a ride out to the airport with him and two other guys from the magazine. The other guys left us at the helicopter and a video guy joined us a while later. I took off two doors, stowed them in the video guy’s truck, handed out life vests, and we climbed aboard. A while later, we were on our way back to the cove south of the bridge.

This flight would be significantly different. There were a bunch of boats to shoot and they were all waiting for us. A soon as they caught sight of the helicopter, they took off downlake. Although I was already moving at close to 100 knots, these guys weren’t planning on cruising at only 50. They were race boats and they wanted to race. With a helicopter.

I caught up with our first target boat and dropped down to lake level. I was flying at 90 knots, 20 feet above the water’s surface, and got a real rush out of the experience. Casey snapped away at each boat — his camera could do 8 shots per second at 8 megapixels — then instructed me to chase down the next one. I’d do what I could — some boats were just too fast and too far ahead to catch up with — and then we’d turn around and head back up the lake looking for other boats to shoot.

This was entirely different from the morning’s shoot, which I now considered a training exercise. This was closer to real life race boat photography. The only difference here is that the drivers weren’t in a real race. They wanted the helicopter to take pictures of them. So when they saw me drop back and pick up another target, some of them turned around and chased me down.

To further complicate matters and make it a bit more challenging, it was after noon and the lake was full of boats. Dodging them became a real chore, but overflying them was not an option at that altitude for safety reasons. There was a slight breeze that occasionally sent a ripple of air over the water — just enough to give the helicopter a vertical wiggle. A downdraft — even a slight one — was not something you wanted when you were only 15 feet off the water’s surface.

Meanwhile, the video guy shot some video out the bubble and through his open door. One of his targets was a boat full of girls promoting David Clark products. We were racing along beside them and he was shooting what was probably excellent video when one of the bimbos on board decided to stand up and moon us.

“What the hell is she doing?” one of the guys said.

“We’ll have to edit that out,” the other guy said.

The guys obviously weren’t amused. Sometimes women can be so stupid that I’m embarrased to be one.

We flew around the lake for about an hour, chasing boats, trying to pass them for bow shots, and sometimes succeeding. One of the boats we were supposed to shoot was having engine problems and was dead in the water. They didn’t shoot any pictures or video.

On the way back to the airport, Casey told me about how one of his photographers had taken a swim in an R22. The pilot had been flying so low along the water that he routinely dragged one or both skids along the water surface. The photographer had asked him several times to fly higher, saying that if he wanted photos from that low, he’d be in a boat. The pilot evidently hadn’t gotten the message. On one of his low dips to the water, he dug the skid in too deeply and it caught. The helicopter flipped over and sank. The pilot and photographer were okay, but I wonder whether the pilot learned his lesson.

I don’t think I’d impressed Casey as much as Todd. I like to think that isn’t my fault — that the boat driver’s desire to race with a helicopter — and beat it — had made me look bad. But my helicopter’s never exceed speed with doors off is 100 knots. How can I be expected to catch up with and pass a boat going faster than that?

I settled up with Casey and spent a half hour relaxing in the FBO while the fuel guy topped off my tanks. (There’s still a price war going on at Lake Havasu City Airport and the fuel at Sun Western Flyers is cheaper than in Wickenburg.) It was about 2 PM when I climbed on board and headed home.

I dropped off the van at the airport, leaving the keys tucked inside the van’s logbook under the seat with a $10 contribution for fuel. It took five tries to get the combination right on the locked gate to the ramp. There was no one around. I walked out to the helicopter just as the sun was rising over Tower Butte and Navajo Mountain to the east. The air, which had been completely still, now stirred to life with a gentle breeze. There was enough light for a good preflight and I took some time stowing my bags and the life jackets so I’d be organized when I arrived at Havasu.

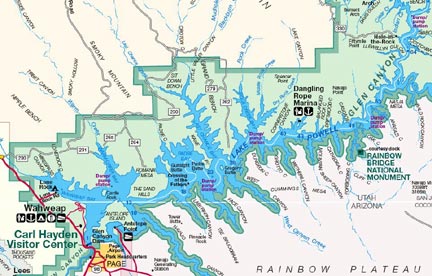

I dropped off the van at the airport, leaving the keys tucked inside the van’s logbook under the seat with a $10 contribution for fuel. It took five tries to get the combination right on the locked gate to the ramp. There was no one around. I walked out to the helicopter just as the sun was rising over Tower Butte and Navajo Mountain to the east. The air, which had been completely still, now stirred to life with a gentle breeze. There was enough light for a good preflight and I took some time stowing my bags and the life jackets so I’d be organized when I arrived at Havasu. I started the engine and warmed it up, giving the engine plenty of time to get to temperature. (Take care of your engine and it’ll take care of you.) At exactly 6 AM — right on schedule — I raised the collective, made a radio call, and took off toward the lake. I swung over the dam for a look and a photo before heading down the Colorado River, over Glen Canyon.

I started the engine and warmed it up, giving the engine plenty of time to get to temperature. (Take care of your engine and it’ll take care of you.) At exactly 6 AM — right on schedule — I raised the collective, made a radio call, and took off toward the lake. I swung over the dam for a look and a photo before heading down the Colorado River, over Glen Canyon. My flight path would take me south along the eastern edge of the restricted Grand Canyon airspace. In a way, it was ironic — less than two years ago, I’d earned part of my living as a pilot flying over the canyon every day, but now I can’t fly past the imaginary line that separates that sacred space from the not-so-sacred space I was allowed to fly. That didn’t mean I didn’t have anything to see. As I flew past Horseshoe Bend and over the narrow canyon, I could see reflections of the canyon wall on the slow moving river below. To the west were the Vermilion Cliffs with Marble Canyon at their base.

My flight path would take me south along the eastern edge of the restricted Grand Canyon airspace. In a way, it was ironic — less than two years ago, I’d earned part of my living as a pilot flying over the canyon every day, but now I can’t fly past the imaginary line that separates that sacred space from the not-so-sacred space I was allowed to fly. That didn’t mean I didn’t have anything to see. As I flew past Horseshoe Bend and over the narrow canyon, I could see reflections of the canyon wall on the slow moving river below. To the west were the Vermilion Cliffs with Marble Canyon at their base. I detoured slightly to the east, keeping to the left of the green line on my GPS that marked Grand Canyon’s airspace. The red rock terrain gave way to rolling hills studded with rock outcroppings and remote Navajo homesteads. I flew low — only a few hundred feet up — enjoying the view and the feeling of speed as I zipped over the ground, steering clear of homes so as not to disturb residents. I saw cattle and horses and the remains of older homesteads that were not much more than rock foundations on the high desert landscape.

I detoured slightly to the east, keeping to the left of the green line on my GPS that marked Grand Canyon’s airspace. The red rock terrain gave way to rolling hills studded with rock outcroppings and remote Navajo homesteads. I flew low — only a few hundred feet up — enjoying the view and the feeling of speed as I zipped over the ground, steering clear of homes so as not to disturb residents. I saw cattle and horses and the remains of older homesteads that were not much more than rock foundations on the high desert landscape. Then there were more homes beneath me and pinon and juniper pines. Wisps of low clouds clung to the mountains at my altitude. Past the mountain I’d been aiming for was the town of Seligman on Route 66 and I-40. I crossed over with a quick radio call to the airport and kept going.

Then there were more homes beneath me and pinon and juniper pines. Wisps of low clouds clung to the mountains at my altitude. Past the mountain I’d been aiming for was the town of Seligman on Route 66 and I-40. I crossed over with a quick radio call to the airport and kept going.

We flew over some of the most spectacular scenery I’ve ever flown over. The lake level is relatively low, but the water is still finding its way into narrow canyons that twist and turn into the sandstone. The rock formations were magnificent; the reddish colors looked incredible against the blue of the water and the partly cloudy sky. It was a bit hazy, making the mountains of Utah look more distant than they really were. But Navajo Mountain was a clearly defined bulk nearby, with snow on the ground among the trees on its north side.

We flew over some of the most spectacular scenery I’ve ever flown over. The lake level is relatively low, but the water is still finding its way into narrow canyons that twist and turn into the sandstone. The rock formations were magnificent; the reddish colors looked incredible against the blue of the water and the partly cloudy sky. It was a bit hazy, making the mountains of Utah look more distant than they really were. But Navajo Mountain was a clearly defined bulk nearby, with snow on the ground among the trees on its north side.