There are only two reasons to do it.

Yes, I’m a helicopter pilot and jewelry artist now. But my second career, which has pretty much wound down at this point, was as a freelance writer. That career, which was in full swing when I started this blog in 2003 (not a typo) was successful enough for me to buy multiple investment properties, completely fund my retirement, take flying lessons, and buy a helicopter.

So yes, I think it’s fair to say that I know a bit about the business of writing.

The Crazy Ghostwriting Offer

So imagine my surprise when I see a tweet from a wannabe writer offering to “ghostwrite your sci fi, fantasy story, ebook, novel” for $5.

My first thought was what kind of desperate idiot would write someone else’s book for $5?

Let’s be clear here: writing may not be terribly difficult — it wasn’t for me — but it is time consuming. The fastest I ever churned out a book was a 280-pager in 10 days. It was my third or fourth book. Would I have taken $5 for 10 days of work? Hell no.

Would I have taken $5 for any piece of writing that had someone else’s name on it? Fuck no.

Ghostwriting Explained

Definition from Merriam-Webster: ghostwrite.

That’s what ghostwriting is all about: writing something for someone else and having that person’s (or another person’s) name on on it as the author. In most (or probably all) cases, copyright goes to the person or organization who hired the ghostwriter. This is a work for hire, which is relatively common in the publishing world.

Ghostwriters are commonly used by famous people with a story to tell — often biographical in nature — who lack the skill, time, and/or desire to sit down and write it. Remember, writing isn’t easy for everyone, there are lots of really crappy writers out there, and writing takes time, no matter how good or bad a writer is. Ghostwriter names don’t usually appear as author, although sometimes they’ll appear in smaller print after “as told to” or something like that.

There’s no glory in being a ghostwriter.

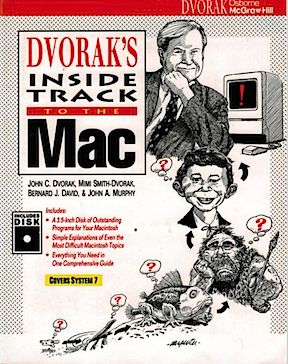

This is the first book I was involved in; I was a ghostwriter on 4 chapters and am mentioned in the acknowledgements.

I know this firsthand. My first book project was as a ghostwriter for John C Dvorak and Bernard J David on Dvorak’s Inside Track to the Mac back in 1991. Bernard hired me, after his agent suggested me, to write one chapter of the book. They liked what I turned in so much that they hired me for another three chapters. (You can read about this in a post titled “Freebies” on this site. I highly recommend reading this if you’re starting out as a writer and hope to make a living at it.)

Much later in my career, I ghostwrote a chapter or two for someone else’s book — was it the Macintosh Bible? I can’t even remember. In that case, I had expertise that the author lacked and the writing experience to get the job done right and on time.

Why Be a Ghostwriter?

Would I ghostwrite something today? Well, that depends. In my mind, there are only two reasons to ghostwrite a book:

- Money. Plain and simple. That’s the only reason I did that second ghostwriting job. They paid me. And it wasn’t $5. (I honestly can’t remember what it was, but at that point in my career, it must have been at least $2,000.) Even that first ghostwriting gig, when I was a complete unproven unknown writer, paid me $500 per chapter — that’s $2,000 total.

- Relationship building. This one is a little grayer. Suppose a publisher/editor contacted me about ghostwriting a book for a famous pilot. Suppose they were willing to pay (more than $5) but it wasn’t quite enough to get me to drop what I was doing and get to work. But suppose that this publisher/editor was building a book series by a bunch of pilots and the series was already popular. There was the definite possibility that ghostwriting this book could lead to more offers. And, if they liked my work enough, I’d be able to negotiate higher fees or other benefits — like an “as told to” byline on the cover — or even royalties on future work. If I thought this offer was a relationship builder that could lead to more or better opportunities in the future, I might go for it. It’s relationship building that I really got from those first four book chapters for Bernard. I co-authored my first book with him and that launched a solo writing career that spanned 85 books and hundreds of articles in just over 20 years.

At every writing opportunity, every writer should be asking one big question: what’s in it for me?

(Haven’t read my “Freebies” post yet? This is a perfect time to go do that.)

Why is this guy offering to write someone else’s book for $5? I can’t imagine — unless he just doesn’t have any ideas and wants someone to feed them to him?

Otherwise, why wouldn’t he just write his own damn book and self-publish it? Then at least his name would be on the cover and he’d own the copyright. He might even make more than $5.

Writers Write

I’ve been a writer since I was 13 years old and wrote stories and book chapters in spiral ring binders. Back then, I tried entering short story contests and failed miserably, not really knowing how to get started, and honestly, not being a very good writer. (I have those old notebooks to prove it; they make me cringe!) But I wrote anyway because I was a writer and the more I wrote — and read, don’t forget that! — the better I got.

(By the way, I write in this blog because I’m a writer. Real writers write. We can’t help it. I just don’t need to make a living as a writer anymore.)

Meanwhile, my family pounded the idea of having a stable career into my head. Writing was not a stable career — at least not in their minds. Being young and foolishly believing that they knew best, I made a wrong turn into a career in auditing and finance, losing 8 years that I could have spent building a writing career. By the time I became a freelance writer back in 1990, I had a home and financial responsibilities. I had to make a living as a writer. There was no going back.

Could I have made a living as a writer if I didn’t analyze every opportunity I found? Of course not. Instead, I’d be banging away at an office job, writing stories, likely never to be published, on evenings and weekends — as I did during my 8 year wrong turn.

The Take-Away

The takeaway is this: if you want to write, write. If you want to make a living as a writer, make sure you don’t sell yourself short. Take only the jobs that will move your career forward — or at least help pay the bills.