It’s not all fun and games.

On Wednesday, the assistant for one of my new clients called. She wanted to know about my availability the following Monday. Her boss wanted to take two companions with him on a flight to seven off-airport landing zones within 100 air miles of his office.

This wasn’t the first flight I’d done for this client. The previous Monday, just the two of us had gone flying to two off-airport landing zones. Two days later, he’d added a companion for a flight to one of those landing zones but had added off-airport pick up and drop off locations. Now, it seemed, he was putting me to the test by filling the helicopter with people for a whirlwind tour of a bunch of properties.

The first two flights were relatively simple, but this last one required some serious information gathering, planning, and math. And that’s the part of real world flying that the flight schools kind of gloss over in their sales presentations and training.

In this post, I want to dissect the planning required for this trip to give folks an idea of what they really need to know to become commercial helicopter pilots.

Feasibility with a Weight Limitation

The very first question that had to be answered was whether or not the flight was possible with my equipment. I fly a Robinson R44 Raven II, which is a remarkably capable helicopter. But every ship has its limitations and I knew as soon as I heard “three men” that I might be bumping up against one of them: weight.

My helicopter, with its new bladder fuel tanks installed, now weighs 1517 empty. Max gross weight — which must include me and the fuel I need to fly, along with my passengers and their stuff — is 2,500. So the first thing I needed to do was calculate the total weight of my passengers plus me, some under-seat gear I usually bring along, and the helicopter and subtract it from the max gross weight.

I asked how much the passengers weighed and got the following information: W: 180, D: 190, A: 240

Normally, I’d add 10 pounds to each person’s weight because everyone lies, but in this case, I knew the numbers were reliable. These folks often fly in a small airplane piloted by my client and I was confident that he got accurate weights from them. I could also weigh them before taking them onboard, but at this point, I wanted to see if the flight was even feasible before I hung up the phone with my client’s assistant.

I did the math on a piece of scratch paper. Me + gear + passengers + helicopter = 2,327 pounds. That’s less than 2,500, so we can fit.

But, of course, we still need to take on fuel — and it has to be enough fuel to get us where we’re going, as well as an airport where we can get fuel if we need it. So more math: 2,500 pounds max gross weight – 2,327 pounds payload (without fuel) = 173 pounds available for fuel.

100LL fuel weighs 6 pounds per gallon. How much could I take? 173 pounds ÷ 6 pounds per gallon = about 28 gallons of fuel.

How long could I fly with 28 gallons of fuel? The helicopter burns 15 to 18 gallons per hour, depending on load. I assumed we’d burn a lot since we would be heavy and I’d be flying at maximum cruise speed. So 28 gallons ÷ 18 gallons per hour = about 1.5 hours.

How far could we go in 1.5 hours? I felt confident that I could maintain an average cruise speed of at least 100 knots. 100 x 1.5 = 150 nautical miles.

Was there fuel available within range? Yes. (After all, it isn’t as if we were flying in the wastelands of Nevada or the Navajo Nation.)

So after all this math, what did I know? I knew that the flight was possible. I could book it.

Planning the Flight So I Know Where to Go

The next challenge was knowing exactly where I had to go. For the previous two flights, we’d had lots of fuel on board and no time issues. I planned the flight based on estimated waypoints, then let my client point me in the right direction to our destinations and guide me to the desired landing zone. Although this worked, it wasn’t the most efficient way to plan and execute a flight. (I can assure you that having a client point in the right direction and say things like, “Do you see that poplar tree?” when you can see about 200 poplar trees within the next five miles is not a very good method of homing in on a destination.) I needed more data in advance.

Although the assistant had initially identified the properties with their names and general locations, that information was pretty meaningless to me. I wanted GPS coordinates that would get me to the property so we could minimize flight time by flying direct. So I did what any computer-literate pilot would do: I asked for addresses.

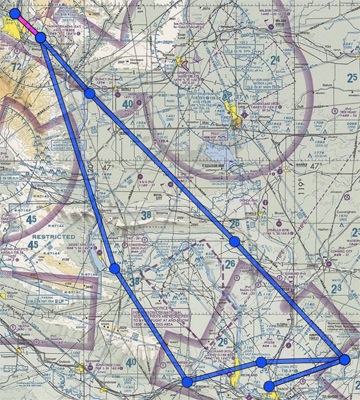

She sent me a list of the property addresses. One by one, I plugged them into Google Maps. I dropped markers and wrote down the GPS coordinates. I then created waypoints in Foreflight on my iPad and plotted the route. It came out to a total of 205 nautical miles. Clearly, we’d need a fuel stop, but if I planned it right, we’d only need one.

Here’s my thinking on this. I was going to be making several off-airport landings into landing zones I’d never seen before. They could be confined spaces, like the location where I was supposed to pick up my client at the start of the flight. (More on that in a moment.) In a confined space, I’d need to make a steep approach and steep departure. This could be difficult to do with a heavy ship, especially as the day warmed up and performance started to decrease. To maximize safety, I wanted the minimum amount of fuel on board when I needed to make these landings and departures.

The plan I came up with (illustrated here) was to visit the first four properties, which would take us to our farthest point from home. While my clients tended to business at that last property, I’d buzz over to the airport to get fuel. Then I’d come back to get them and we’d hit the other two properties on the way home. This fit in well with my client’s plan.

The plan I came up with (illustrated here) was to visit the first four properties, which would take us to our farthest point from home. While my clients tended to business at that last property, I’d buzz over to the airport to get fuel. Then I’d come back to get them and we’d hit the other two properties on the way home. This fit in well with my client’s plan.

This assumed, of course, that I did all my fuel calculations properly and we could go that far. By staying on course throughout, I’d have a much better chance of making it work. Otherwise, we could refuel at an earlier stop — most of the landing zones were near a few airports with fuel.

Knowing When to Say No

Of course, the very first landing zone was going to be a problem. It was in truck loading zone on the side of a hill. There were various obstacles in three directions and a steep approach/departure was required. This was my client’s workplace (or near it) and he wanted me to pick up him and his companions there.

Of course, the very first landing zone was going to be a problem. It was in truck loading zone on the side of a hill. There were various obstacles in three directions and a steep approach/departure was required. This was my client’s workplace (or near it) and he wanted me to pick up him and his companions there.

I didn’t feel comfortable taking off from that landing zone at max gross weight. It was just too tight with no room for error. So I did something some pilots think you can’t do: I said no to the client.

And the client did something that only the best clients do: he said okay. He asked if I could pick him up there and pick up his companions at the airport nearby, which was on the way. Since I knew I’d have no trouble departing from the big ramp area at the airport at max gross weight, I agreed. Problem solved.

Calculating CG to Determine Passenger Seating

So now I knew that the flight was possible and I had a flight plan to make it work. Next, I needed to know where my passengers had to sit to keep the aircraft within CG.

An R44 helicopter is not easy to load out of lateral CG, but longitudinal CG is another story. Unfortunately, I’m not a small person. Put another very big person up front with me with other folks in the back and a light load of fuel and you’ll get an out of CG situation. (This is just one of many reasons why it’s important for a helicopter pilot to stay slim.)

Now, I like to be able to put the biggest person up front with me. Big people usually need more space, including more legroom, and the front seat has more legroom. But when I put 240-pound A up front with me, the CG plot points were outside the envelope. That means that I might not have enough aft cyclic to arrest forward motion. In other words, I might not be able to stop.

Now, I like to be able to put the biggest person up front with me. Big people usually need more space, including more legroom, and the front seat has more legroom. But when I put 240-pound A up front with me, the CG plot points were outside the envelope. That means that I might not have enough aft cyclic to arrest forward motion. In other words, I might not be able to stop.

So I recalculated with the big guy in the back. The plot points slipped back inside the envelope. Problem solved.

So I recalculated with the big guy in the back. The plot points slipped back inside the envelope. Problem solved.

I do want to point out here that in most cases, it really doesn’t matter where passengers sit in my helicopter. It’s just when we’re heavy with a big person up front that there’s a possible problem.

Getting the Fuel Right

Before I conducted the flight, I needed to fuel the helicopter. (I have a fuel transfer tank on my truck that I use when I’m in Washington.) And I needed to be very precise about how much fuel I added. I wanted to add as much fuel as I could to wind up with no more than 28 gallons on board when I picked up the client’s companions at the airport.

More math.

I figured that between warm up (twice), shut down (once), and travel time to the client and then to the airport from his LZ, I’d run the engine about 30 minutes. At 16 gallons per hour — a good estimate for burn rate during solo or otherwise lightweight flight — I’d burn 8 gallons. So when I left my base, I should have 28 + 8 = 36 gallons on board.

Unfortunately, my helicopter does not have precise fuel gauges. Although they’re pretty accurate, they don’t tell you how many gallons are on board. You have to “guestimate” based on the gauges and your knowledge of how the helicopter operates. I’ve been flying this helicopter for 7-1/2 years now, so I have a pretty good handle on it. I figured I had about 6 gallons on board. That means I needed to add about 30.

Another unfortunate thing is that the fuel meter on my truck’s fueling system is inaccurate. It always understates how much fuel is being pumped. I figure it was understating fuel pumped by about 10%. So if I wanted to add 30 gallons, I needed to measure out 33 gallons with the meter.

I can’t make this stuff up.

And yes, if I were smarter, I’d have an accurate stick for the tanks. But I simply haven’t gotten around to making one.

Conducting the Flight

I was due to pick up my client at 7:00 AM at the first landing zone, which was 20 minutes away. I like to get there early whenever possible — it’s never a good idea to make the client wait — so that meant I needed to leave my base at 6:30 AM.

I needed to remove the blade tie-downs, add fuel — I’d gotten back after dark the night before and was too tired to do it then — and preflight. Then I needed to start up and warm up. So after slugging down an excellent cup of coffee, I walked out of the mobile mansion at 6:10 AM.

(That’s another thing flight schools don’t mention — clients don’t usually have bankers’ hours.)

It was a beautiful morning — cool with calm winds. I’m based at an ag strip and I was very surprised that the pilot wasn’t flying. After all, the sun had been up for over an hour and the conditions don’t get any better for spraying crops.

It was a beautiful morning — cool with calm winds. I’m based at an ag strip and I was very surprised that the pilot wasn’t flying. After all, the sun had been up for over an hour and the conditions don’t get any better for spraying crops.

In addition to fueling and doing all my usual preflight stuff, I also cleared every bit of unneeded equipment out of the helicopter. As I loaded this stuff into my truck, I realized that I’d probably been underestimating its weight for quite some time.

The flight to the client’s LZ was uneventful. I arrived right as planned, at 6:50 AM, and shut down to wait.

My client arrived right about 7 and climbed aboard. A short while later, we were picking up his companions. My reading of the fuel gauges had me right around 28 gallons.

We started with the two landing zones I’d already visited with the client. Because they were working at one property, we landed in a slightly different location nearby. But rather than hit the third landing zone, my client asked to skip over it to the fourth. He suggested that we get fuel after that one and, while I was refueling at the airport, he and his companions would drive to the other property. Because they normally fly in a small plane to that airport, they keep a car there.

Using Foreflight for guidance, I found the next property and then followed my client’s directions to a suitable landing zone. It was another tight spot at the bottom of a hill, surrounded by trees and fruit boxes. I was glad I wouldn’t have to take off at max gross weight from that spot.

But as I shut down the engine and they drove off with the man who’d met them there, I started wondering whether we’d actually make the next airport. It seemed that our fuel consumption was higher than I expected. It could have been the added time for the cool down and warm up at each destination. I studied the gauges and didn’t like what I saw. The airport was 15 miles away. I should have enough fuel to make it with the reserve, but would I? Would I see the dreaded low fuel light?

Of course, I worried for no reason. We made it to the airport with fuel to spare. The biggest challenge was finding the FBO ramp at an airport I’d only been to once before — and that time, from a completely different direction. They drove off in their car and I shut down, then went inside to place a fuel order. Then I had lunch: a granola bar and a bag of cookies.

(Yep, that’s another thing the flight schools don’t tell you about: the joys of finding a meal (or a clean bathroom, for that matter) when on a job.)

By the time they returned, time was short. My client had to be back at the office by 1 PM for a meeting. We had enough time to visit one more property, then headed back home. I dropped my client off first, made an easy departure from that confined space with light fuel and just the two bigger men on board, and then dropped them off at the airport.

When I lifted off solo with only about 10 gallons of fuel on board and no extra junk under the seats, the helicopter seemed to leap into the sky, tilting backward at a crazy angle. But that’s only how it seemed after being so heavy all day long.

I was back at my base by 1:30 PM.

Looking Back

I’d flown a total of 3.1 billable hours and had landed at five different off-airport landing zones, two of which I’d never been to.

This was not a difficult job, although planning did require a lot more effort than most of my jobs do. Just figuring out where I was going based on street addresses was a chore that took at least 30 minutes to complete.

But most of our flight time was spent over farmland with very little time over “remote” areas. That takes a lot of stress out of the flight. In the event of a problem, I could always set down at a farm for help. Not so with many of the flights I do in Arizona — some of which are in areas so remote that aircraft have been known to disappear for over a year.

My client and his companions also made the trip very enjoyable. Although they talked business most of the flight, they also joked around with me and answered my few questions about some of the farms and orchards we flew over. After years of flying in Arizona’s desert, it’s quite refreshing to get a view of a whole different world from my seat. Having passengers who can help explain what I’m seeing really makes the flight enjoyable for me.

But I like this client for a more important reason: he understands the value of the service I offer with my helicopter. On the way back, we talked about how much time it would have taken to drive to the same places. They agreed it would have taken at least 7 or 8 hours just do do the driving. We did it in six, including stops as long at 30 minutes in some places. And although my client could fly faster in his plane, he can’t land at each of the properties. He has to spend additional time driving between them and the closest airport. A helicopter can land onsite — that saves time, too.

For people who know that time is money, money spent flying is money well spent.

Here’s an example of a Sikorsky S-55C. Photo from

Here’s an example of a Sikorsky S-55C. Photo from  Cherry drying is very unforgiving work. In most cases, you’re hovering less than 40 feet off the ground over treetops at less than 10 miles per hour. That’s right, smack dab in the

Cherry drying is very unforgiving work. In most cases, you’re hovering less than 40 feet off the ground over treetops at less than 10 miles per hour. That’s right, smack dab in the

The plan I came up with (illustrated here) was to visit the first four properties, which would take us to our farthest point from home. While my clients tended to business at that last property, I’d buzz over to the airport to get fuel. Then I’d come back to get them and we’d hit the other two properties on the way home. This fit in well with my client’s plan.

The plan I came up with (illustrated here) was to visit the first four properties, which would take us to our farthest point from home. While my clients tended to business at that last property, I’d buzz over to the airport to get fuel. Then I’d come back to get them and we’d hit the other two properties on the way home. This fit in well with my client’s plan. Of course, the very first landing zone was going to be a problem. It was in truck loading zone on the side of a hill. There were various obstacles in three directions and a steep approach/departure was required. This was my client’s workplace (or near it) and he wanted me to pick up him and his companions there.

Of course, the very first landing zone was going to be a problem. It was in truck loading zone on the side of a hill. There were various obstacles in three directions and a steep approach/departure was required. This was my client’s workplace (or near it) and he wanted me to pick up him and his companions there. Now, I like to be able to put the biggest person up front with me. Big people usually need more space, including more legroom, and the front seat has more legroom. But when I put 240-pound A up front with me, the CG plot points were outside the envelope. That means that I might not have enough aft cyclic to arrest forward motion. In other words, I might not be able to stop.

Now, I like to be able to put the biggest person up front with me. Big people usually need more space, including more legroom, and the front seat has more legroom. But when I put 240-pound A up front with me, the CG plot points were outside the envelope. That means that I might not have enough aft cyclic to arrest forward motion. In other words, I might not be able to stop. So I recalculated with the big guy in the back. The plot points slipped back inside the envelope. Problem solved.

So I recalculated with the big guy in the back. The plot points slipped back inside the envelope. Problem solved. It was a beautiful morning — cool with calm winds. I’m based at an ag strip and I was very surprised that the pilot wasn’t flying. After all, the sun had been up for over an hour and the conditions don’t get any better for spraying crops.

It was a beautiful morning — cool with calm winds. I’m based at an ag strip and I was very surprised that the pilot wasn’t flying. After all, the sun had been up for over an hour and the conditions don’t get any better for spraying crops.

The sky was intensely dark out toward the river and the storm was definitely heading in my direction. But what was even scarier was the low hanging cloud near me that seemed to be swirling gently like something from a Weather Channel tornado special. I watched it for a while, wondering whether the storm was really intense enough to get a tornado going. It didn’t seem to be.

The sky was intensely dark out toward the river and the storm was definitely heading in my direction. But what was even scarier was the low hanging cloud near me that seemed to be swirling gently like something from a Weather Channel tornado special. I watched it for a while, wondering whether the storm was really intense enough to get a tornado going. It didn’t seem to be. I came in over the orchard in a grand, swooping arc, settling in at the southeast corner in a hover over trees nearly as old as I am.

I came in over the orchard in a grand, swooping arc, settling in at the southeast corner in a hover over trees nearly as old as I am.