Why waste time flying around the airport or hogging up the runway when you just want to get on the ground?

Note: A version of this post originally appeared in

AOPA’s Hover Power blog. If you’re a helicopter pilot, you owe it to yourself to check in there regularly to read great articles written by experienced helicopter pilots.

Over the past nine or so years, I’ve done more than my fair share of long cross-country flights with newly minted commercial pilots or CFIs. In most cases, the purpose of the flight was to reposition my helicopter at a temporary base of operations 500 or more miles away and the typically 300-hour pilot on board with me was interested in building R44 time. I was on board as a passenger and got a chance to observe the things these pilots did — or didn’t do. I think the fact that I’ve never been a flight instructor gives me a unique perspective on what I observed.

One thing I’ve come to realize is that typical flight training does very little to prepare students for a commercial flying career. Instead, students are taught to perform maneuvers “by the book,” often so they can teach those maneuvers to their own students in the future. While it’s obviously important to know how to perform maneuvers properly, there are other concerns that are important to commercial pilots. In my upcoming posts for Hover Power, I’ll tackle a few of them, starting with traffic patterns.

I can tell lots of stories about new commercial pilots and CFIs entering traffic patterns to land for fuel at nontowered airports in the middle of nowhere. I can even tell you about the pilot who landed on the numbers of an empty airport’s runway, hover-taxied to the taxiway, and then hover-taxied a half mile down the taxiway to reach the midfield fuel island. They did this because that’s what they had been trained to do. That’s all they knew about landing at airports.

Our flight training teaches us a few things about airport operations, most of which are school-established routines at the handful of airports where we train. There’s a procedure for departing flight school helipads and there may be a procedure for traveling to a practice field nearby. Once there, it’s traffic patterns, over and over. Normal landing and takeoff, steep approach, maximum performance takeoff, run-on landing, quick stop, autorotation–all of these standard maneuvers are taught as part of a traffic pattern. It gets ingrained into our minds that any time we want to land at an airport, we need to enter a traffic pattern.

The reality is very different. Remember, FAR Part 91.129 (f)(2) states, “Avoid the flow of fixed-wing aircraft, if operating a helicopter.” Your flight school may have complied with this requirement by doing a modified traffic pattern at the airport, operating at a lower altitude than the typical airplane traffic pattern altitude of 1,000 feet, or landing on a taxiway rather than a runway. But despite any modifications, it’s still a traffic pattern.

But is a traffic pattern required for landing? No.

Experienced commercial pilots — and their savvier clients — know that traffic patterns waste time. And while the pilot might not be concerned about an extra few minutes to make a landing, the person paying for the flight will be. Why waste time flying around the airport before landing at it? Instead, fly directly to or near your destination and land there.

Before I go on, take a moment to consider why airplanes use traffic patterns. They enter on a 45-degree angle to the pattern to help them see other traffic already in the pattern. They then follow the same course as the other planes so there are no surprises. This is especially important at nontowered airports that don’t have controllers keeping an eye out for traffic conflicts.

But helicopters are avoiding this flow, normally by flying beneath the airplane TPA. As long as they stay away from areas where airplanes might be flying — remember, avoid the flow — they don’t need to worry much about airplane traffic. Instead, they need to look out for other helicopters and obstacles closer to the ground. If a runway crossing is required, special vigilance is needed to make sure an airplane (or helicopter) isn’t using the runway to take off or land. Obviously, communication is important, especially at a busy airport when a runway crossing is involved.

Now you might be thinking that this advice only applies to nontowered airports, where the pilot is free to do what he thinks is best for the flight. But this can also apply to towered airports.

Airport controllers who are accustomed to helicopter traffic and understand helicopter capabilities may instruct you to fly to and land at your destination on the field. You must be prepared to do this, even at an airport you’ve never been to before. That’s part of what your preflight planning is all about. Consult airport diagrams or even satellite images of the airport. Know where you’ll be flying from and where you need to park. Imagine the route to that spot. Be sure to take note of where the tower is–it’s often a great landmark for navigating while close to the ground. Never assume the controller will put you in a traffic pattern. And don’t be afraid to admit you’re unfamiliar if you didn’t do your homework or if things in real life look different from how they looked on paper or a computer screen.

What if a controller does instruct you to enter a traffic pattern and you don’t want to? As amazing as this might seem to new pilots, you can ask the controller to allow you to go direct to your airport destination.

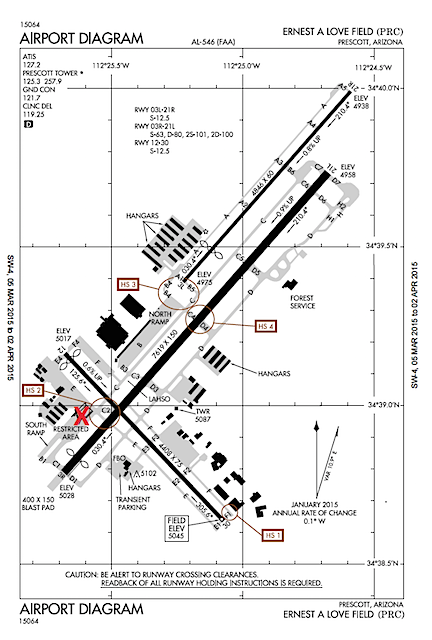

The airport diagram for Prescott. The X marks the location of the restaurant and we were coming in from the west. Runways 21L and 21R were active. The tower instructed us to fly all the way around the south end of the airport, at least three miles out, to get into a pattern for Runway 21.

I’ll never forget the flight I had one day as a passenger on my friend Jim’s Hughes 500c. Jim was a retired airline pilot who had been flying helicopters for at least 10 years. We were flying into Prescott Airport (PRC) in Arizona for lunch. When Jim called the tower, he asked for landing at the restaurant. The controller told Jim to enter a traffic pattern that would have required him to fly all the way around the airport, taking him at least 10 minutes out of his way. “Negative,” Jim barked into his microphone. “One-Two-Three-Alpha-Bravo is a helicopter. We want to land direct at the restaurant.” A new pilot at the time, I was shocked by his tone of voice. There was an uncomfortable silence and then the controller came back on and told him he could fly direct to restaurant parking.

Will the tower always grant your request? It depends on the situation. If a runway crossing is involved and the airport is busy with traffic, they might not. It might be safer or more convenient for them to keep you in a pattern with the airplanes. But it can’t hurt to ask, although I don’t think I’d be as aggressive as Jim was that day.

One of the big challenges of becoming a commercial helicopter pilot is thinking like a commercial helicopter pilot. There are things we can do that seem to conflict with what we were taught. Landing at airports without the formality of a traffic pattern is one of them.