A memorable photo flight and tour of an amazing aircraft.

The first call came from Global Supertanker over a month ago. Would I be interested in working with an aerial photographer to shoot dry runs and water drops made by the world’s only 747 air tanker?

The answer came with only a few thoughts of what this might entail: sure!

Possible aerial video job next month: shoot 747 tanker dropping water in a ravine. Sounds like fun.

— Maria Langer (@mlanger) May 7, 2016

But because about 50% of the calls I get to fly Flying M Air‘s helicopter on unusual missions never actually happen, I didn’t get my hopes up too much. I tweeted about it briefly and mentioned it on Facebook. Then I filed it away in the back of my mind and got on with my life.

Until last week. That’s when another call came. And another. Soon I was taking down the names and phone numbers of contacts involved with the demo flight and photo shoot. Checking my calendar for availability and weather resources for forecasts; yes, Monday could work. Getting briefed over the phone about what they wanted to do and how I would help them get the video footage they needed.

I was very excited about the job — and not because of the potential earnings for a few hours of flight time. You see, it’s not always about money to me. It’s often about the opportunity to do something new and different, to meet people who are part of a different world, to participate in a program that’s interesting, to expand my horizons and learn new things. That’s a big part of what my life is about, that’s what drives me to wander down the paths I’ve chosen. It’s about taking on new challenges to make things happen.

And what could be more of an interesting challenge and learning experience than flying a videographer above a 747-400 air tanker as it drops 20,000 gallons of water over a Washington forest?

The date and time was set for Monday, June 20. I’d need to get to Moses Lake, WA by 7 AM so the photographer could install his equipment and I could get briefed with the flight crews of the two planes we’d be shooting.

A Busy Weekend

But I had plenty of other flying to do before then.

Friday was a training day, with me spending about an hour and a half practicing autorotations with Gary, one of the owners of Utah Helicopter, who is also a flight instructor and part of Flying M Air’s cherry drying team. Gary is a great instructor and I did pretty well, actually nailing the spot for a 180° autorotation twice in a row. (I didn’t tempt fate by going for a threepeat.) Afterwards, my helicopter got a 50-hour inspection, which is mostly an oil and filter change and spark plug cleaning.

Friday was also the day one of my Facebook friends excitedly announced, “The Boeing 747 Supertanker just landed at Tucson.” He was under the impression that it was there to fight the wildfire at Show Low, AZ. That got me wondering whether there were two of them. I soon learned that there was just the one and that the only reason it had stopped in Tucson was to refuel before flying on to Moses Lake. Truth is, the Global Supertanker hasn’t been certified yet; I’d be participating in part of the certification process here in Washington.

Saturday was a crazy flying day with rain most of the day and 7 hours of tedious flying over cherry trees. I figure I personally dried about 200 acres of cherry trees, including more than a few orchards that got dried two or three times. My team flew just as much, if not more. While it’s nice to get all those revenue hours, I dread long, widespread rain events like the one we had Saturday. It’s stressful for everyone and exhausting.

Sunday was a lot more enjoyable and nearly as busy, with seven Father’s Day flights, including two short ones for my next door neighbors and one for my mechanic and his family that included a flight down to Blustery’s in Vantage, WA for milk shakes. 5.3 hours logged.

And then there was Monday.

Prepping to Fly

Despite waking up at about 4 AM — I get up very early here in the summer — I got off to a late start. I’d planned 30 minutes to get to Moses Lake, but lifted off at 6:35.

Flying M Air’s helicopter parked at Moses Lake with the Global Supertanker.

The sky worried me. It was cloudier in the area than I’d expected based on the forecast and the radar showed rain to the southwest moving northeast, right toward the Wenatchee area. Not a good day to be taking off to the east. Although I’d never be more than 45 minutes flight time from my base, I did not want to break off from the photo flight to dry cherries. Fortunately, I had two pilots in Wenatchee who could cover the orchards. As long as it wasn’t another widespread rain event, we should be okay.

I made it to Moses Lake on time. I set down on the lone helipad in front of the Million Air FBO at almost exactly 7 AM. No one was around, but the big plane was parked on the ramp behind me.

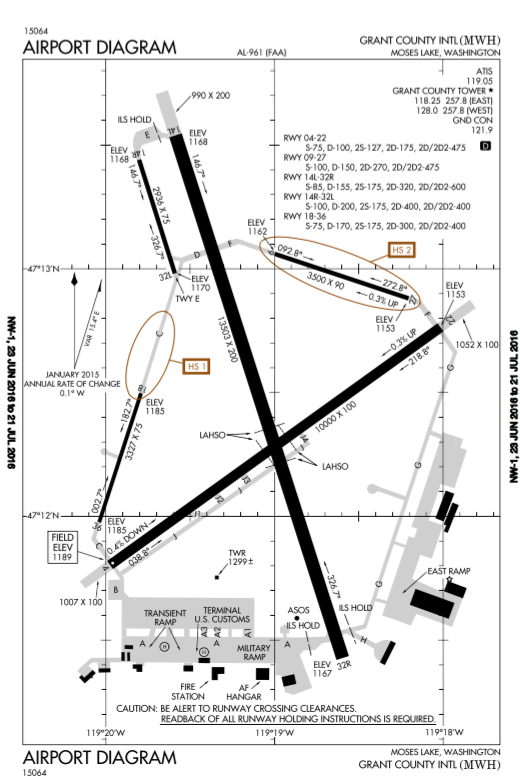

Moses Lake is a huge, underutilized airport.

I should say a few words about Moses Lake’s airport, Grant County International. First, it’s huge, with five runways, the longest of which is 10,000 feet. A former military airport, it still has a military ramp. It also has a U.S. Customs office, two FBOs that provide fuel, and a handful of flight schools. There’s a control tower but no airline service, despite a very nice terminal building. It’s used by Boeing to test fly 747s coming out of the factory in the Seattle area. They fly them over the Cascade Mountains, land them at Moses Lake, and then fly them around to work out any bugs before delivering them to clients. It’s the only airport I know where you can occasionally see 747s flying standard — but admittedly wide — traffic patterns and doing touch-and-goes. With a Boeing facility on the field, it was an obvious choice for the Global Supertanker people to continue work on their certification process.

Million Air doesn’t sell 100LL, the fuel my helicopter takes. It only sells JetA. But Columbia Pacific, which was supposed to open at 8 AM, sells 100LL. As I went through the shutdown procedure, I saw activity at its hangar and decided to try raising them on the radio. I’d need both tanks topped off before the flight. I got a line guy on the radio and put in a fuel order. He promised to get to it when he was finished with the other plane he was fueling.

I went inside the FBO to look for one of my contacts. It was a while before I connected with the photographer, Tom, who was piling gear on the floor after multiple trips out to his car. He’d driven in from Seattle with his camera mount, a brand new video camera, and a ton of other equipment. He asked me to move the helicopter closer to the building and I was in the process of going out to do so when the fuel guys arrived. Before they could finish, Tom had come out to the helicopter with one of the FBO line guys and his gear and began setting up. I removed the rear passenger-side door for him, stowed it in a Bruce’s Custom Covers door bag I had, and brought it into the FBO office for safekeeping.

Back in the FBO, I waited outside the conference room where a meeting of the pilots, FAA inspectors, and other program personnel was going on. While I waited, an FAA inspector came up to me and introduced himself. He asked if I was the pilot of the helicopter and when I told him I was, he told me he’d ramp-checked me. I was surprised and I think my expression revealed that. He laughed. “Don’t worry. You passed. Everything is fine. But I do need to get some info from your pilot and medical certificates.” I handed them over.

That’s when two things happened. First, I was called into the meeting. Second, my phone started ringing. Caller ID showed it was one of my cherry drying clients. I apologized and excused myself, took the call for an orchard drying request, hung up, and called one of my pilots to give him the job.

I was introduced to those assembled and put a few of my business cards on the table for those who wanted one. Then I was briefed, through map images on a laptop, of the planned routes and what my position needed to be. I got important information such as flight altitudes, operational frequency, and radio calls for various parts of the flight. The operating area was a place called Keller Butte, which was about 50 nautical miles north northeast on the Colville Reservation, not far from the Grand Coulee Dam. There was a fire tower there and one of my contacts was already there with a few other people to do photography from the tower. The other two aircraft was the 747-400 Global Supertanker and the lead plane, a King Air, which would do “show me” flights and then guide the larger plane to the drop zones for both dry and live runs. There were two planned run routes at or below 5,000 feet elevation in the hilly terrain around the Butte.

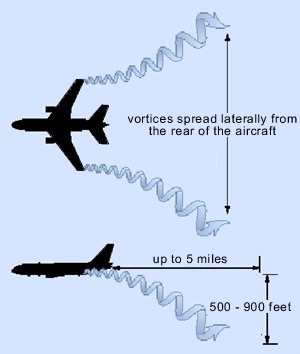

Wake turbulence, illustrated. The best way to avoid it is to stay far away or above the plane.

My main concern, of course, was wake turbulence from the 747. Wingtip vortices from the big plane’s wings trail out and down. If I flew too close to the plane — especially at a slightly lower altitude, I could be caught in them. Only a week before, I’d been caught in the relatively minor wake turbulence caused by a Dash 8 at Wenatchee. I was far enough back that it wasn’t an issue, but I certainly did feel it. Getting even that close to a 747 configured for a low pass would be catastrophic for me and my aircraft. The solution was to stay above it. I asked about altimeter settings so we would all be dialed in the same way. One of the pilots said we’d start with the setting for Moses Lake and then update it in flight. They said they wanted me at least 200 feet above. I was thinking 500 feet.

I got and made another call while I was in the meeting. Those attending were surprisingly understanding. Now both of my Wenatchee pilots were flying. I knew that if the cherry orchard acreage started adding up beyond the point where my guys could cover it promptly on their own, I’d have to leave to help them. This would inconvenience my new clients and ruin any possibility of future work with them. But when I stepped out of the meeting and consulted Wenatchee area radar, I saw that whatever cells had moved in were already moving out or dissipating. There would be no more calls.

Before the meeting broke up, I was introduced to my front seat passenger, Phil from the FAA. So yes, I had to conduct a complex photo flight with an FAA inspector sitting next to me. No added stress, huh?

Tom’s camera mount. The camera is facing the wrong direction in this shot.

Meanwhile, Tom, the photographer had set up his camera on a weird hanging mount in the left rear seat. Its heavy padded base sat on the passenger seat with a pole that provided a hook for his camera. The seatbelt held it securely in place, making an STC unnecessary. The camera hung from a bungee cord contraption and had two Kenyon KS-6 gyros attached to it. Tom would sit in the seat beside it and shoot through the window.

I admit I wasn’t happy with the setup. There were two reasons:

- The camera’s lens was at least 10 inches inside the cabin door. That meant that he’d have less panning range before the door frame came into view. (The Moitek camera mount I have makes it possible to mount the camera with the lens at the door opening, right inside the slipstream. That maximizes the potential range without worries about wind buffeting.)

- Putting the camera on the opposite side of the aircraft from the pilot with a passenger sitting beside the pilot made it virtually impossible for me to see what he was seeing. At times, my passenger also blocked the target aircraft from view. But although I suggested that he mount the camera behind me, he said that the mission required it to be where it was. I still don’t see why that was so, given that with a variety of runs and angles, we shot pointed in either direction. But the customer is always right, eh?

Still, there was nothing seriously wrong with the setup. It just made more work for me and the photographer and limited his capabilities. So once I’d conducted my required FAA flight safety briefing — using the briefing card, of course, mostly for the benefit of my FAA audience — and satisfied myself that nothing would fall out the open doorway, I climbed aboard with my passengers and started up.

The Shoot

I beelined it to Keller Butte, did a lot of maneuvering there, and then beelined it to Wilbur Airport for refueling.

The flight to Keller Butte was uneventful. I chatted mostly with Phil. Because rushing air coming in through the open doorway was getting into Tom’s microphone, I had to turn off voice activation. That kept Tom quiet, mostly because he had so much stuff between the seats that he couldn’t reach the push to talk (PTT) button. Later, when we were set up to shoot, I’d turn voice activation on.

We crossed the farmland north of Moses Lake, the desert north of there, and the wheat fields north of there. Then we crossed over Roosevelt Lake, which is the Columbia River upriver from the Grand Coulee Dam. Electric City was just west of us and during the course of the day, we spotted the Grand Coulee Dam several times. (We even did a flyby on our way to refuel.) Keller Butte was one of two small mountains just north of the lake. We zeroed in on the higher of the peaks and saw the fire tower right away.

Then it was time to wait. There was no landing zone up there — why don’t they build helipads near fire towers? — so we had no choice but to circle. By then I was tuned into our agreed upon air-to-air frequency. The folks at the fire tower had handheld VHF radios and kept us informed on what they knew about the other aircraft based on phone calls they were apparently getting from Moses Lake.

Then I heard the King Air pilot coming in. As he got closer, he asked about my position and I told him. He got me in sight and began circling and practicing the runs.

Then the Supertanker’s pilot called in. He also needed to know where I was. I stayed close to the tower, realizing that he was coming in at a higher altitude than the 5500 feet I was maintaining. Fortunately, he joined up in formation flight with the King Air far enough away to make wake turbulence a non-issue for me. They got right down to business, prepping to make the first “show me” run. I moved into the agreed-upon position and climbed to 6000 feet while they descended.

The “show me” run is where the lead plane does the actual run that the tanker needs to do. The tanker pilot stays higher, following him and watching where he flies. The lead plane’s pilot announces when he’s on the line, where the drop should begin, where the drop should end, and when he’s clear. He peels off to one side and the tanker normally peels off to the other. They then regroup with the smaller, more maneuverable plane joining back up with the tanker.

There’s a lot of radio chatter during all this as they synchronize speeds, talk about positions, and establish run altitudes. I stayed quiet unless I thought they needed to hear from me or asked me a question. Phil listened and observed intently. In the back, Tom apparently couldn’t hear the radio chatter and had to be filled in, over the intercom, about what was coming next.

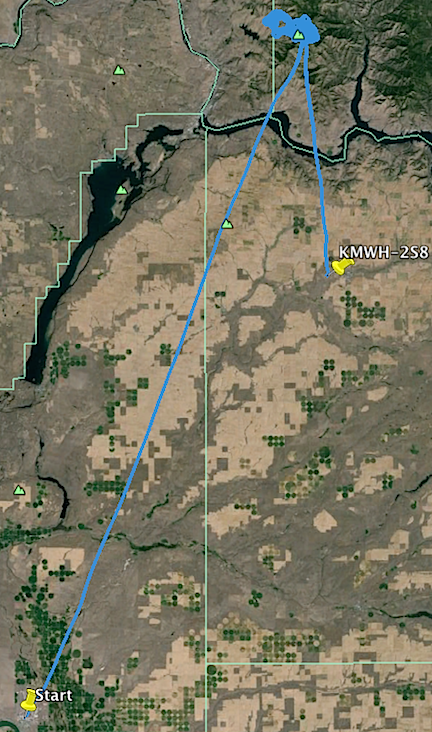

Foreflight’s track log feature recorded the details of my flight path. Looks like spaghetti, no? This was just the first flight.

My job was mostly to hover in position with the camera facing the action. Because the camera’s panning range was so limited, I also had to pivot the helicopter so Tom could track the big plane. There was about a 10 knot wind up there and depending on which direction we were facing, maintaining that hover and smoothly conducting that pivot ranged from easy to near impossible. Over the course of the day, I’d get into and (obviously) recover from settling with power twice. Once, a quartering tailwind whipped us around almost 90° before I caught it. But, in general, I did an acceptable job. The biggest challenge was facing a target that I sometimes could not see. Fortunately, the choreography of the runs and shoot position — as well as my front seat observer — made it unnecessary for me to worry about midair collisions.

This went on for nearly two hours. A “show me” run followed by several dry runs followed by a live run with a full drop — which was awesome to see from the air — followed by more dry runs. Tom missed the live run because of camera focusing issues. The two planes moved to the other run location and I shifted position accordingly. Then another cycle of runs. But because they were out of water, there was no live run. They checked in with me when I still had an hour of fuel left. Then did three more runs before announcing bingo and heading back to Moses Lake to refuel.

We didn’t need to go so far. The closest airport with fuel was Wilbur, WA, 20 nautical miles south southeast. It’s basically a paved ag strip with a handful of hangars and a set of fuel pumps for 100LL and JetA. We landed and someone came over to help us with the pumps. There was no credit card system, so I gave him my mailing address and he promised to send a bill.

We hung out for a while. Although the Global Supertanker can refuel and refill with water/retardant in 30 minutes, they weren’t doing it that day. We were told it would be at least 90 minutes. So we killed time by visiting the ag operator’s hangar, finding and using a restroom, and talking. The folks there were very nice. And Tom, the photographer, showed me how to do a trick panorama shot like this one:

Seeing double Tom? This shot is remarkably easy to make, right in the iPhone’s camera. All you need is a model who is quick on his feet.

I was glad I’d brought along some water. My passengers had, too. There was nothing within walking distance of the airport except wheat fields. The town was in a clump of trees about two miles away. I nibbled at some salad I’d brought for lunch, then put it away. I could wait.

We took off when we figured enough time had passed. It was a short flight back to Keller Butte, where the guys in the tower — now lounging on chairs in the parking area below — told us neither plane had taken off yet. Eager to save fuel, I demonstrated a pinnacle approach and slope landing for the FAA inspector on board. Tom got out and soon disappeared a way down the hill. What is it about men peeing outdoors?

When I heard the King Air pilot make his call, I called Tom back. When he was strapped in, I took off and circled back up near the tower. And then we repeated what we’d done earlier with a variety of drop runs, two of which were live. This time, Tom got the footage. So did Phil, on his phone’s camera:

Phil took this picture with his phone. Not bad through plexiglas.

I was just relieved that Tom had captured footage of the drop. It was very stressful to do all this costly flying, wondering whether he’d succeed and satisfy himself and his client.

This went on for another two hours with lots of hovering and circling and pedal turns. Then we all went back for fuel for another run — the two planes to Moses Lake and me to Wilbur by way of the Grand Coulee Dam, which neither of my companions had ever seen.

Me, Phil, and Tom. Now you know why I don’t share selfies: I suck at taking them.

This time I fueled up by myself, making the required entry in the fuel sale log book. (Things are pretty laid back in farming communities.) An older gentleman drove up as I was fueling, apparently excited about seeing the helicopter come in. His name was Phil, too, and he and Phil and Tom chatted. I walked back to the hangar to see if I could track down some W100Plus oil for my helicopter — it’s been burning more oil than usual lately, probably because of the engine’s age — and came back with a quart of W100 oil, which would do in a pinch. Then the ag service owner came over and chatted with the guys for a while. I ate my salad and finished a bottle of water. I took a selfie of us.

At 3:30 PM, it was time to go back. We loaded up, I started up, and we took off. We beat the two planes back again, but not by much. It seems that they’d discussed a new run and drop zone while they were in Moses Lake and wanted to do it. They had me hang out south of the tower while they did a “show me” pass to show the big plane, the guys who had been in the tower and were now on a road below it, and me. I picked a spot north of the new run area and told them I’d stick to 6500 feet or higher. Then I watched a few more practice runs while Tom shot video. I practiced and then nearly perfected a forward move that kept us from getting into settling with power and gave me more control over the direction I was able to point the helicopter, making it easier for Tom to get smooth shots.

But I also watched the planes. It was amazing how close that 747 could get to the treetops.

That went on for about an hour, with one big live drop. And then it was over — at least for us. They told us we were done. The two big planes peeled off to the west and I dropped altitude, ducking behind the ridgeline as I headed south. We continued listening to them for a while on the radio. Then, 20 miles out from Moses Lake, I switched frequency and they were gone.

The After Party

I got back to Moses Lake and set the helicopter down near the front of the FBO so Tom wouldn’t have to lug his equipment so far. Then I placed a fuel order. I didn’t even hear the Supertanker land and taxi into its parking spot behind us.

Phil urged me to ask for a tour. There was nothing I wanted more. Trouble was, the plane was in a part of the airport ramp that was not accessible to pedestrians. I asked the fuel truck driver to take Tom and me over and he started to. But then he got to some pavement markings and told me he couldn’t drive across without a green badge. He drove us back to Million Air.

I went inside and asked a guy in an office if he could help us get to the big plane. He very kindly came outside and drove us over in a golf cart. He let us off between the 747 and King Air and Tom immediately went to the King Air to retrieve some of his equipment. I told the FBO guy that I’d find my own way back and thanked him for the ride.

The staircase was quite inviting.

I walked over to the big plane, snapping pictures most of the way. On the other side, a long stairway had been set up between the pavement and the door. One of the plane’s pilots, Marco, was there, inviting me in for a tour. He had the King Air pilot, Jamie, with him and another man who did work for the FAA. I climbed the stairs and joined them for a tour.

Marco explains what the tanks are for and how they work.

I could probably write an entire blog post about the inside of that plane. Formerly a cargo plane, the entire lower level had been stripped out. The front “first class” section remained empty — at least that day — but the back was configured with a collection of cylindrical tanks for air, water, and retardant. The air is used as a “plunger” to force the water and retardant out of the four ports at the bottom of the plane. The system is set up to make up to eight drops with a load. The retardant system can hold two different kinds of additives and drop them with water in any configuration. There’s an extensive leak detection system and a whole procedure for handling leaks in flight. Our guide told us all about it as we climbed over and crawled under huge white pipes.

I actually broadcast this first part of the tour on Periscope, but when the audience level did not rise above 10 viewers, I stopped the video so I could take photos instead. Here’s the video; I’m afraid it isn’t very good due to the tight quarters.

The upstairs first class cabin is pretty much intact for use by the ground crew.

I look ridiculously excited here, sitting in the First Officer seat of a real, operating 747.

Now that’s a cockpit.

It was my first — and likely my only — time strolling under a 747.

From there, we went up a sort of ships ladder to the top level. The original upstairs first class cabin was intact; with seats for 12 people, it was used to carry the ground crew to each mission. There were some computer controls in a room behind that. Then the cockpit with its sleeping bunks in a tiny room off to one side. I was invited to sit in the First Officer’s (co-pilot’s) seat while the FAA guy sat in the Captain’s seat. We took pictures of each other like tourists while the two pilots talked behind us about the plane’s systems.

Afterwards, we climbed back down the ships ladder and the main stairs to the pavement outside. I wandered around under the plane, checking out the enormous landing gear and engines and looking up into the four discharge ports that could disperse almost 20,000 gallons of water or retardant over a 3 kilometer path. Around me, workers were tending to the plane: fueling it, filling it with water, cleaning its windscreen. It was the focus of attention even as it just sat their idle, waiting for its next flight.

I looked across the pavement at my helicopter and realized that the two aircraft had a lot in common. They were both used for a purpose, pampered between flights, and respected by their pilots.

As I headed for the Million Air’s shuttle bus, I stopped to chat with one of the men working on the plane. He asked me if I had a challenge coin.

“A what?” I asked.

Is this a cool souvenir or what?

“Here,” he said. “I think we have a few left.” He went into a box on the front seat of a van nearby and produced a heavy coin in a protective plastic sleeve. He handed it to me and I thanked him. It’s a great keepsake of the day’s events.

The van drove us all back to the FBO. Jamie and Marco went inside and I walked back to my helicopter. I’d already put the door on and was all ready to go. I took a last look at the big plane I’d been flying over most of the day and wondered if I’d ever see it again. Then I climbed on board, started up, and headed home.

When I shut down, I discovered I’d flown a total of 7.3 hours.

—

Postscript: As evidence of a day spent dancing on the anti-torque pedals, for the first time ever, my calves were sore in the morning.

Scammers/Spammers will say and do anything. Here’s proof.

Scammers/Spammers will say and do anything. Here’s proof.