Fascinating work with a lot of very specialized equipment.

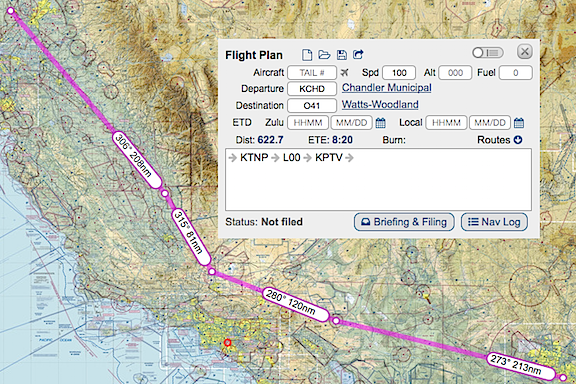

My friend Sean runs a helicopter spraying operation. (You might know about this kind of work by another name: crop dusting.) The business is highly regulated not only by the FAA to ensure that operators and pilots have the skills and knowledge to do the work safely from an aviation perspective, but also by state and local agencies concerned with the safety of the chemicals being sprayed. It also requires a ton of very costly specialized equipment, from spray rigs that are semi-permanently installed on the helicopter to navigation equipment that helps the pilot ensure chemicals are spread evenly over crops to mixing and loading equipment to get the chemicals into the helicopter’s spray tanks.

Sean’s helicopter with spray gear. He was running rinse water through the system on the ground here.

A lot of people have asked me why I don’t go into this business. Although I’d love to fly spray jobs, I have absolutely no desire to invest in the required equipment, start selling spray services to potential clients, or deal with the government agencies that need to get involved for each job. Or have employees again.

Sean is just getting his business off the ground (no pun intended) after over a year of spending money on equipment and jumping through hoops with the FAA. While I wouldn’t say he’s struggling, he’s certainly motivated to complete contracts and collect revenue. Unfortunately, it’s not the kind of work a pilot can do cost effectively without help. He needs at least one person on the ground to mix and load chemicals, refuel the helicopter, and keep the landing zone secure.

Sean was having trouble finding someone to do the job. It’s not because he isn’t paying — I think he’s paying pretty good. Trouble is, a lot of folks either (1) don’t want a job that doesn’t guarantee a certain number of hours a week or (2) don’t like physical labor. Because the job depends on when there’s a contract to fulfill and what the weather is like when the job needs doing, hours are irregular. And it is tough physical work.

Here I am in my coveralls, hamming it up for a selfie between loads.

I know because I stepped up to the plate to help him with his first two big jobs. I thought I’d spend a bit of time talking about this work from the loader’s point of view.

The Job

The pilot’s responsibilities are to spread the loaded chemicals over the crops to be sprayed using the tools in and on the helicopter. I can’t speak much about that because I haven’t flown a spraying mission. I can tell you that in a light helicopter like the Robinson R44, the pilot is doing a lot of very short runs — sometimes only a few minutes — and is often spending more time getting to and from the spray area than actually applying the spray. For that reason, the landing/loading area needs to be as close to the crops as possible — usually somewhere on the same property. The pilot is taking off near max gross weight for most flights and landing relatively light. And there are a lot of take offs and set downs. As I told Sean the other day, doing spray runs is a lot like doing hop rides at fairs and airport events — you just don’t need to talk to your passengers.

The loader’s responsibilities — well, that’s something I can address since I’ve been wearing that hat for the past two weeks.

When the pilot is warming up the aircraft for the first flight of the day, the loader is mixing the first batch of chemicals. Sean’s current setup includes a mix trailer that holds 1600 gallons of fresh water, a Honda pump, a mix vat, and a dry mix box. With the pump running, I turn valves to add 50 gallons of water to the vat, which is constantly mixing. Then I add about 4-6 capfuls of an anti-foam agent (which is not HazMat) to the vat, followed by a specific amount of chemical provided in 32-ounce bottles.

Sean’s mix trailer onsite at an orchard near Woodland, CA. This is the “business end.” The mix vat is on the left.

This is how the chemical we’re using is shipped: in 32-ounce bottles.

The chemical we’ve been using is a “broad spectrum fungicide for control of plant diseases” made by Bayer (yes, the aspirin people). It is highly regulated and must be kept under lock and key when not in use. It looks a lot like Milk of Magnesia, which was a constipation remedy my grandmother gave us when I was growing up. It doesn’t smell as good, though. (And I’m certainly not going to taste it.) If you’re not familiar with that, think of an off-white Pepto Bismol. We’re spraying this stuff on almond trees and there’s a definite deadline to getting it done.

Here’s where some math comes in. The guy who wrote up the specs for our client’s orchard wants 6.5 ounces of the stuff applied per acre. The helicopter can take 50 gallons of chemical mix at a time. That 50 gallons covers 2.5 acres. So how much do I need to put into the vat for each 50 gallon load? 6.5 x 2.5 = 16.25. Round that down to the nearest whole number for 16. This is an easy mix because the chemical comes in 32 ounce bottles and there are measuring tick marks on the bottle at 8, 16, and 24 ounces. That makes it easy to add half a bottle and get it right. But if it didn’t work out so smoothly, we could use a big measuring cup Sean has to get the right amount.

So I add the chemical and the mixer mixes it up. If I’ve finished the bottle, I need to rinse it, which I do by dipping it in the mixer and then swishing it around a few times before dumping it into the mix. Then I put the empty bottle away in a box; even the empties are accounted for at the end of a job.

As you might imagine, I’m wearing protective gear: rubber gloves and coveralls. This particular chemical isn’t very nasty and I’m not likely to breathe it so I don’t need to wear a respirator or anything like that. (If I did, I probably wouldn’t be helping out.)

All this tank filling and mixing takes me less than 2 minutes.

I timed one of our cycles. Lap 1 was skids down to skids up: my loading work. Lap 2 was skids up to skids down: Sean’s flight. Less than 4 minutes for a cycle.

When Sean is ready for chemical, I turn the valves on the trailer’s mix system to direct mixed chemical into a thick long hose with a specialized fitting at the end. I bring the fitting over to the helicopter, drop down to my knees (which is why I also wear knee pads), and mate the hose fitting to a fitting on the helicopter’s tank. I then turn a valve on the hose fitting to get the mix flowing into the helicopter. I watch the mix vat the whole time and turn the valve off when it gets near the bottom so I don’t run it dry. Then I get back up and use a pull cord on a pump on the same side of the helicopter to start up his pumping system. When that’s running, I give Sean a thumbs up and head back to the trailer, gently resting the hose fitting on the hose along the way.

I timed this once and it took just over a minute, but that’s because it took two tries to get the helicopter’s pump going.

Sean lifts off immediately — often while I’m still walking away — and I get back to work mixing the next batch. When I’m done with that, I wait until Sean returns. It’s usually less than 4 minutes. Then I’m turning valves on the trailer quickly, sometimes before he even touches down. My goal is to minimize load time so he can take off again quickly.

Here’s Sean coming in for a landing beside the trailer. And yes, his approach route for a while was under a set of wires. (The rest of the time, he was departing under them.)

I usually leave the pump on the whole time I’m in the loading area, although if Sean’s work area is more than a minute or two from the landing zone, I sometimes shut it off. I wear ear plugs or earbuds so I can listen to music while I work. I keep a radio in my pocket so I can hear Sean if he calls for something or warn him if there’s a problem with the landing zone.

Beyond Mixing/Loading

Every six or seven runs, Sean needs fuel. He often radios ahead, but if he doesn’t or if I don’t hear the radio, I can tell he needs fuel because he throttles down to idle RPM (65%) after landing or makes a hand signal. In that case, I’ll fill the chemical first and return the hose to its resting position, then turn on the fuel pump on his truck, and walk the hose over to the passenger side of the helicopter. Sean said fueling is usually done by walking around the back, but no one can pay me enough money to walk between a helicopter’s exhaust pipe and tail rotor while it’s running. So I walk around the front, dragging the hose under the spray gear to get into position. Then I pump fuel until he gives me a signal to stop. It seems to me that he’s half filling the main tank each time — that’s about 14 gallons less whatever he already has in there.

When I’m done, I cap the tank, carefully walk the hose around the front of the helicopter to the truck, and then go back to start that pesky helicopter pump. Thumbs up and he takes off. I usually remember to turn the fuel pump off. Then I mix another batch of chemical so I’m ready when he returns.

Occasionally his pump or mine needs fuel. He uses helicopter fuel — it’s just 100LL AvGas — for both pumps. He keeps a jug of it at the mix trailer. I do the fueling.

Keeping the landing zone secure is pretty easy. On our last job, we were in a nice concrete loading area for a hay operation. Trucks did come and go, but in most cases, they saw Sean landing or sitting in the landing zone and waited until he was safely on the ground or had departed. Twice I tried to signal trucks to stop when I saw him coming in but they didn’t — both times they didn’t see the signal until it was too late and Sean aborted the landing. In our current landing zone, which is a dirt patch at the edge of the orchard, there’s a truck that comes and goes to haul out dead trees cut into firewood; the driver of that rig seems to pay attention and stops when I signal him.

Getting Physical

The job is extremely physical. All day long I’m walking around the trailer, truck, and helicopter; climbing up and down on the trailer’s mix station and truck bed; and hauling heavy hoses, fuel jugs, and cartons of chemical. And dropping to my knees (and then getting up) when I load the helicopter. And don’t even get me started with the pull cord on the helicopter’s pump, which I apparently pull too hard half the time.

I move at a quick pace, but I don’t run. Running is dangerous. Too easy to trip on a hose or a skid. Too many very hard things to crack your skull on if you fall. Anyone who runs while doing this job is an idiot.

But it can’t be too physical, right? After all, I’m a 55-year-old woman and I’m not in the best of shape. And I’m doing it all — although I’m exhausted at the end of the day.

Hours and Break Time

The job is weather dependent. We can’t work if it’s raining or likely to rain. We can’t work when the wind is more than 7 or 8 knots. We didn’t work Sunday because it was raining on and off all day and very windy.

But when we can work, we start early. We’re typically at the landing zone about an hour before dawn. Usually, Sean gets there first since he has more to do to get ready. He fills his truck’s fuel transfer tank with 100LL from the local airport. That can take 20-30 minutes. Then he comes back to the landing zone and, if the water tank is less than half full, he hooks it up to his truck and drags it to his water source and fills it. That’s another 20-30 minutes. Then he brings it back to the landing zone and positions it based on the wind direction, slipping 4×4 pieces of wood under the trucks rear wheels to bring the front end of the trailer up.

By that time it’s nearly dawn and I’ve arrived. I prep my work station by setting out chemical and anti-foam bottles in the trays on one side of the trailer and boxes for the empty bottles on the other. I suit up in the coveralls and get my knee pads on. While he’s preflighting the helicopter, I’m mixing the first batch of chemicals so I can load as soon as he starts up.

We work pretty much nonstop until we’re out of water. More math: If the trailer’s tank holds 1600 gallons and we’re using 50 gallons per load, we can do roughly 32 loads (1600 ÷ 50) before we’re completely out of water. That’s two 8-bottle cases of chemical. It’s also 80 acres. If you figure an average of 6 minutes per spray run/loading cycle, that’s about 3-1/4 hours.

When we’re out of water, I get my break because Sean has to fetch fuel and water using his truck. There’s nothing too difficult about doing any of it, but since I can really use a break after working that hard for that long, I won’t volunteer to do it. Instead, I strip off my protective gear, wash my hands (if I can), and take Penny for a walk. (She waits in the truck while I’m working.) Or sometimes I run out and get a bite to eat. Or eat a snack I’ve brought with me. That break lasts about an hour. Then it’s back to work all over again for another 3+ hours.

At the end of the day, we run three rinse cycles through all the equipment. I “mix” batches with just water. The first one usually includes some anti-foam stuff because the foam really gets out of hand if I don’t. The second two are straight water. I purposely overfill the mix tank on the third run to make sure the water gets all the way up the sides. Each load gets pumped into the helicopter and sprayed out to clean the spray rig.

The most difficult thing I did on Saturday was to get this container open so I could lock up two cases of chemical.

Then we wind up the hoses, secure the helicopter — or bring it back to base if Sean is near his hangar — lock up any unused chemicals and empty bottles, and call it a night. By that time, it is night; we often do the rinse cycles in the dark. I bring a lantern so I can see.

It’s long day. A very long day. I’ll start at 6 and finish by 7 with two hour-long breaks in the middle of the day. That’s 11 hours of active work.

On Saturday, we worked for most of the day. Yesterday was Sunday and we would have worked all day if the weather was right. There are no “weekends” in this line of work.

So yeah: this job wouldn’t be very attractive to someone who prefers to sit on his ass all day.

But I’m getting a great workout. I know I am because every single muscle in my body was screaming at me this morning when I got out of bed. No pain, no gain, right?

Right?

Why I’m Doing It

Although Sean is paying me for this work and the pay isn’t bad, I’m not doing it for the money. I’m doing it for two reasons:

- Sean is a friend and he really needs to get this business off the ground. Without a helper, he’d have to mix and load by himself. He’d likely only get a fraction of the acreage done each day. The first orchard I helped him with was 1,000 acres and he did have another part time helper. This one is about 500 acres and there is no other helper. It would take him well over a week to do it by himself. Together, we’ll knock it off in less than 4 days.

- I have a natural curiosity about how things work. The best way to learn about something is hands on. I know a lot more about the spray business now than I did two weeks ago and that’s a real motivator for me.

We’re down in Turlock, CA for this job. It’s 100 miles from Sean’s base near Woodland, which is also where I’m camped out for the next few weeks. Although I wanted very much to bring my camper down here with me and live in the orchard, Sean needed me to tow the mix trailer while he towed his helicopter.

Here we are on Friday morning, just before dawn, ready to head down to Turlock with the mix trailer behind my truck and helicopter trailer behind Sean’s.

I’m very glad I let him have his way. We’re staying in very comfortable rooms at what’s probably the nicest Best Western I’ve ever stayed in. After months of mostly living in my camper, I admit that it’s nice to have a good, long, hot shower every day. So that’s a bonus.

And isn’t that what life is all about? Doing different things? Seeing different things? Experiencing different things?

That’s what it’s all about for me.

But I admit that I do hope Sean finds a new helper for his next job. I’m not staying in California much longer and I’m ready to hang up my spray loader cap.

For the record, I have never liked Facebook. Search this blog and you’ll find more than a few posts where I’ve bashed Facebook in one way or another. (

For the record, I have never liked Facebook. Search this blog and you’ll find more than a few posts where I’ve bashed Facebook in one way or another. (