Another ferry flight with a pilot friend.

[Note: I’ve been working on this post for the past two weeks. Just so busy with other things! Finally got it done today. Better late than never, no? (Cynics need not answer that one.)]

For the fifth February in a row, my company, Flying M Air, has been contracted by an almond grower to provide frost protection for one of his Sacramento-area ranches. Frost protection is one of the lesser-known services a helicopter pilot can provide. We basically fly low-level up and down rows of trees to pull warm air from a thermal inversion down into the tree branches where developing crops — in this case, almonds — are growing. Almonds are susceptible to frost damage for a 4 to 8 week period starting around the time that flowers are pollinated. Because the temperatures are most likely to be lowest at night, most of the flying is done then or, more likely, right around dawn.

Before the Trip

My helicopter had been in Chandler, AZ (near Phoenix) since October when I dropped it off for its 12-year/2200 hour overhaul. Although it technically didn’t need to go in for overhaul until January 2017, I needed it done by mid-February for this work. The overhaul, which I blogged about here, takes a minimum of three months to complete, so I made sure the excellent maintenance crew at Quantum Helicopters got an early start. I don’t fly much in the winter anyway and planned to fill my downtime with some snowbirding, most of which would be in Arizona and southern California. I like snow, but not months of it, and I really do need to be in the sun in the winter time. I’ve structured my work life to give me time to go south every winter.

Director of Maintenance Paul Mansfield pulls my R44 out of the Quantum hangar after its overhaul on February 20, 2017. At that point, I hadn’t flown for four months and I was ready.

I picked up the helicopter on Monday, February 20 and spent much of the week flying it around Arizona with friends: up the Salt River, to Wickenburg, to Bisbee for an overnight trip, and to Sedona for breakfast. Along the way, I got to fly some familiar routes and see some familiar sights: along the red rock formations of Sedona, down the Hassayampa River Canyon, over the Salt River lakes, and over herds of wild horses in the Gila River bed. I needed to put some time on the helicopter to make sure there weren’t any problems before I left the area.

A lot about the helicopter felt or sounded different — and I tell you, you really get to know an aircraft when you’ve put over 2000 hours on it in 12 years. The auxiliary fuel pump sounded different, the blades sounded different, and the engine start up felt different. I immediately noticed that it was running at a higher cylinder head temperature. The guys who worked on it assured me that was normal until the rings on the newly rebuilt engine were set and I took it off mineral oil, which was recommended for the first 50 hours. The belts were also too loose when the clutch was disengaged and needed to be adjusted. And my strobe light, which had been working intermittently when I dropped it off, was now not working more often than it was. These were all minor things and I had them taken care of on Friday afternoon, when I flew it back from Wickenburg to Chandler. While I was there, the head of maintenance offered to do an oil change and, since the oil was getting dirty, I let his crew do it. I suspect the strobe light fix — which required a new part — was the most bothersome of all the fine-tuning work they did. They’d keep it in their hangar overnight.

My ride from Chandler to Mesa with Captain Woody at the controls.

While they got to work, my friend Woody picked Penny and me up in Chandler in his company’s newly leased R44 — with air conditioning, that he had turned on, likely to impress me (it worked) — and flew me to Falcon Field in Mesa, where his company is based. For some reason, I decided to live broadcast the flight via Periscope — how often do I get to be a passenger? — and Periscope decided to feature it. Soon 450+ people were watching our progress across the Chandler/Gilbert/Mesa area. By the time we’d landed, over 4,000 people had seen all or part of it. I think Woody got a kick out of that.

Woody, Jan, and Tiffani operate Canyon State Aero, a helicopter flight school that also does tours and aerial photo work. They have a modest fleet of Schweizer 300s, plus the newly added R44 and an R22 that should arrive next week. I hung around the office while they finished up paperwork and other things, occasionally answering their questions about R44s and R22s. I’m hoping to see that R44 again in Washington this summer for cherry drying.

Afterwards, Jan, Tiffani, and I went out for dinner. We tried for seafood and wound up with Chinese food. Back at their house, we talked and drank wine and watched some amazing time-lapse videos of the desert on Netflix while Penny played with their dogs and stared at their cats. I had an allergic reaction to something — likely the cats — and made the mistake of taking two Benadryl. That pretty much knocked me out for the night.

I woke up early (as usual), feeling refreshed and allergy-free. Woody showed up around 7:30 AM. After some coffee and goodbye hugs all around, Woody, Penny, and I hopped into Woody’s Prius and headed back to Chandler. We hoped to be off the ground by 9 AM.

Getting Started

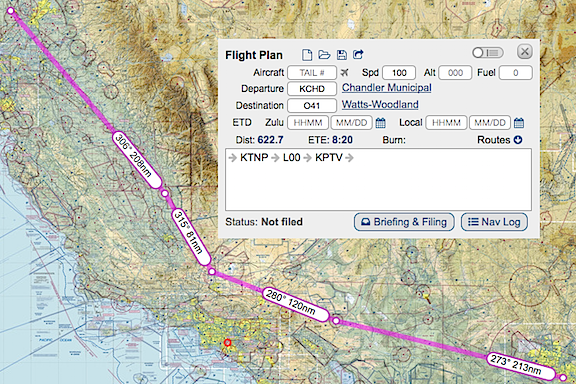

I’d planned the flight via Foreflight, with fuel stops at Twentynine Palms and Porterville, CA. The total time was estimated at about 6-1/2 hours with a slight headwind. It was a variation of a flight I’d done a few times before, starting with a solo R22 flight in the 2003 from my Wickenburg home to Placerville, CA and ending, most recently, with the 2013 trip that took my helicopter out of its Arizona hangar for the last time and brought it to California for its first frost season. This was the first time I’d be doing the route from Chandler and I worried a bit about making it all the way to Twentynine Palms for fuel. There aren’t any fuel options between Blythe and Twentynine Palms, so having almost enough fuel to get there wasn’t an option. But Foreflight and my own personal experience with the helicopter said I could do it, so that’s what I planned.

Our planned route, as shown on the SkyVector website. Good thing we didn’t fly today when I plotted that for illustration here; there’s a 22 knot headwind.

The weather was absolutely perfect for flying. I’d been monitoring various forecasts for points along our route and it all looked good with the possibility of some wind in the Tehachapi area and a slight chance of rain near our destination. Visibility was good. It would be a bit cool — even in the California desert — but the helicopter has good heat if we needed it. I was looking forward to a good, although somewhat long, flight.

Woody would fly. Woody’s an airline pilot nearing retirement. He’s got a bunch of hours in helicopters and recently got his R44 endorsement. Now he was interested in building some time in R44s. We agreed that he’d pay for fuel — which accounts for less than 1/3 of my operating costs — for the whole trip in exchange for stick time. I didn’t need the time — I have about 3500 hours in helicopters (R44, R22, 206L) — and I’d been flying around all week. And I really don’t mind being a passenger once in a while, especially with a good pilot at the controls. Still, I sat in the PIC seat and he sat in the seat beside me, using the dual controls.

Penny, of course, sat in the back. The back of the helicopter was completely full of stuff, including the wheeling toolbox I’d brought along to hold helicopter parts and accessories — think headsets, charts, log books, etc. — while the overhaul crew stripped down the helicopter to its frame, my luggage, Woody’s luggage, Woody’s pilot uniform, a box of Medifast food (long story), and Penny’s travel bag. I’d forgotten to bring along a bed for Penny, so I folded up my cotton sweatshirt and put that on top of the toolbox for her. She perched up there and slept for most of the flight.

Chandler to Twentynine Palms

I took off from Chandler, crossed the runway per the tower’s instructions, and struck out almost due west. As soon as I got to cruising altitude — 500 feet above the ground (AGL), which was 1700 feet above sea level (MSL) — I offered the controls to Woody. He took them and I settled back for the first leg of the flight.

We flew west along the south side of South Mountain, where we saw a flight of four Stearman airplanes. Woody was pretty sure he knew one of the pilots, but since we didn’t know what frequency they were on, we couldn’t raise them on the radio. (We tried 122.85, 122.75, and 123.45, which are common air-to-air frequencies around Phoenix.) I was kind of surprised to see that we were gaining on them and eventually passed them. (Did I mention that my helicopter is now about 10% faster than it was before the overhaul and now cruises easily at 110-115 knots?) We crossed the north end of the Estrella Mountains just south of Phoenix International Raceway (PIR), mostly to avoid having to talk to the tower at Goodyear. We did tune in, though, and that’s how we learned that Luke Approach was closed so we wouldn’t have to talk to them to cross Luke’s Special Air traffic Rule (SATR). Woody wasted no time getting right on course; I’d already dialed my Garmin 430 GPS in to KTNP for Twentynine Palms.

Flight of four Stearman planes, in formation.

Captain Woody flying past some mountains in California near the Colorado River.

There wasn’t much of anything exciting for the next two hours. We crossed over Buckeye Airport as another plane was coming in, flew north of the steaming cooling towers of the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant, paralleled I-10 for a while, and then drifted north of it, crossing SR60 just east of where it joined I-10. Then we crossed a little mountain range and entered the Colorado River Valley about halfway between Parker and Blythe. The Colorado River was a ribbon of blue snaking from north to south beneath us. Then we were in the southern reaches of California’s Mohave Desert, crossing a sandy desert landscape that looked as inhospitable as the Sahara but without the tall dunes. Woody kept pretty close to the GPS track, but did detour around the tallest parts of any mountains in our path. Our altitude varied from 300 to 1000 feet AGL, depending on where we were. For a good portion of the flight, we were the only living things in sight.

There’s a whole lot of nothing in the California desert between Joshua Tree National Park and the Colorado River.

I did a lot of talking, telling Woody about the helipad on top of Harquahala Mountain where I’d landed my R22 years ago and later my R44, and sharing some of the stories of my flights with low-time pilots who had done ferry flights with me over the years. We agreed that most helicopter pilots didn’t get much real-life experience as they built time as flight instructors. He asked me a bunch of questions about my time working for Papillon at the Grand Canyon. I told him about the excellent learning opportunities a season at the Canyon offered, but lamented about the fact that some of my coworkers had been either immature or cocky head cases. We talked a little about pilots we’d known who had died flying. We agreed that it was ironic that so many people said “he was a great pilot” about pilots who had died in crashes; if he was so great, why was he dead? (There are old pilots and bold pilots but no old, bold pilots.)

We flew through the very northernmost edge of Joshua Tree National Forest, along a road there. When the park fell away to the south, the abandoned buildings started up, one after the other. It was as if hundreds of people had made sad little homes on five-acre lots out there, only to abandon them to the desert wind years later. Many of them had completely blown away, leaving only concrete slabs and scattered debris. I remembered this part of the flight very clearly from my other trips through the area and didn’t take any photos this time around. But if you look on a zoomed-in satellite image of 29 Palms Highway east of Twentynine Palms, you’ll see what I’m talking about. It’s kind of eerie.

A satellite image from Google of an area east of Twentynine Palms shows a sample of the scores of abandoned or wrecked buildings out in the desert.

We reached the airport in just over two hours — which is about 15 minutes quicker than I’d planned for. (All my flight plans are for 100 knots airspeed; I’d rather over-estimate time than underestimate it, especially when flying out in the desert.) Woody landed in front of the pumps. We cooled down the engine and shut down. Woody handled the fueling while I cleaned the windows and then added a quart of oil. An old guy with a taildragger flew in and came to a stop nearby; he’d wait for us to leave before refueling. A friend of his drove into the airport and they chatted for a while. They came over to look at the helicopter and Penny, who I’d let out to get some exercise and take a pee. Woody used the bathroom and I took a picture of the helicopter. Then we all climbed back on board, I started up, and I took off to the west.

Zero-Mike-Lima at Twentynine Palms.

Twentynine Palms to Porterville

The next stop was Porterville, which was in California’s Central Valley. Unfortunately, we couldn’t fly a direct path to the Porterville because of the restricted airspace between it and Twentynine Palms. So I plotted a course that took us to Apple Valley and Victorville and on to Rosamond before climbing over the pass at Tehachapi and then dropping down into the Central Valley. The route would keep us clear of all the restricted airspace, including Edwards Air Force Base, which is east of Rosamond at the edge of a not-so-dry lake bed.

The desert west of Twentynine Palms was almost as empty as the desert east of it — but not quite. There were homes and small communities scattered about the immediate area, growing ever more rare as we continued west. After a lot of mostly empty desert, the population climbed as we passed near Lucerne and Apple Valley. Woody talked to Victorville’s tower and got permission to cross over the top — we were the only one the controller talked to the whole time we were tuned in. There were dozens of planes mothballed on the tarmac beneath us.

Some of the planes stored at Victorville.

We passed near El Mirage Lake, another dry lake bed that Woody knew from gliders or racing or something I’ve forgotten. Then more empty desert in an area the chart warned us had Unmanned Aerial System operations below 14000 feet. We tuned into Joshua Approach’s frequency as the chart suggested, but never did hear anything about drones.

Then we were south of Edwards Air Force Base and could see the huge dry lake bed where they occasionally landed the space shuttle off in the distance. But because of all the rain California had been having, it looked more wet than dry.

We turned the corner of the restricted airspace and Woody steered us northwest, over the town of Rosamond, where I had the misfortune of being stuck overnight once back in 2003, and toward the windmills on the south side of Tehachapi Pass. There had been windmills — or, more properly, wind turbines — on that hillside for as long as I could remember, but every time I came through the area, there seemed to be more. This time, I decided to share the view on Periscope. Although my voice couldn’t be heard above the sound of the helicopter’s engine and blades, I moved the camera around a lot, showing off the turbines, Woody, and even Penny perched atop the rolling toolbox in back.

The foothills of the Sierra Nevada, on the west side, just north of Tehachapi. Despite the gray day, they were very green.

We crossed over the pass and began the descent down the other side into California’s Central Valley. It was like a completely different day. On the south side of the pass, in the desert, it had been mostly sunny, bright, and warm. But on the north side, it was mostly cloudy, gray, and cool. But the foothills were so lush and green!

Our flight plan had us heading northwest bound through the valley with our next fuel stop in Porterville. As usual, I tuned in the radio for the next closest airport so we could listen in on any traffic and make a radio call if necessary. There wasn’t much to hear or report on.

When we landed at Porterville, we found a nice looking Bell 47 already parked there. We squeezed in in front of it. While Woody handled the fueling, I wiped down the windows, and Penny began exploring our surroundings, the helicopter’s owner and a friend came out. “You’re from Washington!” the helicopter’s owners — whose name I’ve already forgotten (sorry!) — exclaimed. It turns out that he reads this blog and put two and two together when he saw me. (After all, how many red R44s are piloted by a woman who often travels with a small dog?) We all chatted for a while and Woody asked for a picture of us with my helicopter. Penny made new friends, too — a pair of small dogs that hang out in the airport office. Woody and I visited the rest rooms before climbing back on board, starting up, and continuing our trip.

Woody and I posed for a photo with the helicopter at Porterville.

Porterville to Woodland

The last leg of the trip wasn’t very exciting. We flew over a lot of farmland — California’s Central Valley is a major food producer — including more than a few almond orchards in full bloom. We’d already been in the air for more than four hours and I was ready to be at the destination.

One of the many general aviation airports we passed near or over as we made our way northwest through California’s Central Valley.

One by one the small general aviation airports ticked by beneath us or within sight: Visalia, Selma, Fresno Chandler, Madera, Chowchilla, Oakdale, Lodi, Franklin.

Just past Stockton is when I began to notice the flooding below us. Farmland inundated with water. A broken levee. Closed roads. When we reached the Sacramento River and ship channel, we saw a sea of silty water with occasional “islands” of homes and equipment yards. It was sobering.

A few shots (through Plexiglas) of the flooding we flew over just south of Sacramento, CA.

Just past Davis, I asked for and took the controls. I wanted to overfly Yolo County Airport, where I was based last year. The orchard I’m contracted to cover for frost season is adjacent to it; I wanted to fly by and see the condition of the orchard and trees. There was no flooding down there — at least not that I could see — and the trees were in full bloom. Pallets of beehives were scattered among the trees. Business as usual.

I steered us north and zeroed in on our final destination, a small privately owned airport nearby where my camper was already set up and waiting for me. A while later, I was touching down at the fuel pumps, ready for Woody to top off the tanks after our long trip. Once that was done, I started it back up and hover-taxied to a parking spot on the ramp.

Then I was on to my next adventure with Woody and Penny: getting a cab to take me to where my truck was waiting, having dinner at one of my favorite restaurants in town (I highly recommend the venison osso buco), and driving Woody to Sacramento International Airport for his flight back to Arizona. I returned to the helicopter to retrieve my luggage not long after dark and, a few minutes later, was letting myself into my camper where I was soon dead asleep after the long day.

Postscript

The arrangement I had with Woody worked out for both of us, especially since fuel prices have come way down in recent months. He got more than six hours of flight time that cost him less than $500; I saved about $500 on fuel, got company for my flight, and even got treated to dinner with cocktails when we arrived at our destination. And because Woody is an airline pilot, he was able to catch a company flight back to Phoenix at no cost. Win win.

I didn’t mind letting Woody do the flying. I’d put about 10 hours on the helicopter since picking it up from overhaul and knew I’d be putting more time on it soon. Sometimes its nice to be a passenger — especially when you have confidence in the flying capabilities of the guy at the controls. (With a certain “Sunday pilot” flying, I’d rather remain on the ground.) I got to sit back, take a few photos, and enjoy the scenery.

Best of all, my helicopter is now officially back at work, earning me money — even while parked in a deluxe hangar in California.

Discover more from An Eclectic Mind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hi, Maria. Just felt like mentioning that I’m enjoying your blog and appreciate your effort. (Think we all need a little encouragement and appreciation for our efforts every so often :)!)

Well, thanks so much! And you’re right: we all do! It really makes me happy when folks participate in comments, especially when they say nice things. It reassures me that I’m not wasting my time at the keyboard.

Must be good to be back in the saddle.

Your photos from the north make Ca look just like England, while the desert and wilderness shots further south seem to be from another planet. Amazing contrast.

When we were in Calistoga some of the wine growing areas used old rotary aero-engines mounted on pylons, to stir up the night air and keep the frost at bay. We were told they were from B17s but to me they looked like something you might see on a Stearman. It is hilly around there so I suppose that is the only method which is safe in that terrain?

It feels GREAT to be flying again. I’ve had a few really good flights since I got the helicopter back. Hope to go out again on Wednesday or Thursday, maybe to Napa Valley or at least to check out the Oroville Dam.

The most amazing thing about the lush green of the foothills and the stark emptiness of the desert is that they’re less than 50 miles apart. The variety of environments and terrains in this country is absolutely amazing. For the past few days, I’ve been working in the flat farmland of California’s central valley, yet when I look to the east I can see a line of snowcapped mountains, the Sierra Nevada. Not far to the north, is the southernmost end of the cascade Mountains which are volcanic in nature. And of course, to the west, is the Pacific ocean. California has it all.

We call what you saw “wind machines” and yes, they do look like they could come off old airplanes. At least the ones in the wine country of California do. They also use them in Washington state’s orchard areas, which is why there isn’t any frost protection by helicopter up there. I’m not sure why they don’t use them in almond country. It could be because it so vast and the number of wind machines needed to cover it would be costly. In hilly areas, cold spots develop in low pockets and I think wind machine should might be very effective moving the air around.

Boy, those photos bring back some memories! I’ve flown that route several times and in the area quite a bit, both for the military and civilian. I’ve never seen anything like that flooding in northern California though, every time I’ve been over that area it was desperately dry. It’s sort of mind-boggling to see such a huge change, CA has been in a drought for so long I guess we all just assumed it would be like that perpetually. Not so, apparently.

I’ve done some frost control work in far southern AZ, in a Bell 206. The company I worked for at the time (out of Sedona) must have been well down on the orchard managers list though, since we always seemed to get the call in the late evening / middle of the night to be there for the following morning. It’s a terrible way to run things safety-wise, since you don’t get a chance to look over the location in the daylight before you end up flying there in the dark. Frankly, I’d never do that again, it’s far too easy to end up hovering into an unseen wire or tower even when you KNOW they’re there, let alone depending on the landing light to spot it. Thanks for posting the photos too!

My one criticism would be about your reference to old/bold pilots, and those who have died flying helicopters. Probably every pilot in the business has heard about a crash and thought “I’m surprised it took this long to happen, that person (usually a guy) was a reckless idiot/overconfident moron/just plain stupid”. Aviation is ruthless at sorting out those who depend on good luck as a routine part of their flight planning; helicopter pilots in particular rarely get a chance to make a major mistake more than once. While it is absolutely true that pilots largely create their own “good luck” by exercising good judgement and respecting the limits of their machines, their environment, and themselves, there is no getting around the fact that flying is undeniably a business that involves risk.

If you stay in the helicopter business long enough you will inevitably end up hearing about the crash/injury/death of a pilot that you know well, and thought of as a “good” pilot. One who’s judgement and skill you respected, that you thought well of, and who you’d never have expected to hear about on the news. Perhaps it will even be a pilot who you thought of as more experienced and more skilled than yourself, or that you learned from. Whether you call it fate or bad luck or just random chance, there is always an element of risk that you can never completely eliminate, regardless of how assiduously you work at it.Sometimes bad things just happen to good people, despite their best efforts. For that reason alone, I try to always give the benefit of the doubt to those who have died in aviation incidents/accidents/crashes.

They handle frost differently here. My contract requires me to keep the helicopter near the orchard, which means I need to deliver it onsite. I usually meet with the grower or someone knowledgeable about the orchard who shows me what I need to fly or at least provide me with maps. Then, during daylight hours, I scout the orchard from the ground and often from the air. I create a map using software on my iPad to outline the orchards boundaries and I take careful notes about obstacles like wires. Then, when I’m called out — which is normally between 330 and 4 PM — I go to the helicopter and prep it for possible flight. (If I’m back home, that means hopping on an airliner to arrive in the area before midnight.) That’s what I call active standby. If they need me to fly, they usually call sometime between 2 AM and dawn but most likely closest to dawn when it’s already starting to get light out. Still dangerous flying in the dark, but I feel fully prepped.

As for my comments regarding old, bold pilots, after I wrote it I began to suspect that someone might take issue with it. You are right, of course. Although most accidents are due to pilot error in one way or another, there are instances where the cause really could be blamed on the aircraft or some other circumstance that the pilot was either not aware of or could do nothing about. It’s a risky business — but so is driving a car or walking across a street. Smart, careful people do what they can to minimize the risks, but shit happens. Is that bad luck? Possibly. I believe we make our luck.

A while back, I wrote a blog post in which I mentioned a hotshot pilot I knew who did a lot of aggressive flying. I had been with him when he flew us under a bridge crossing a narrow canyon — something I consider pretty risky. A few years later, he crashed an R22 in a narrow Canyon in Utah. I immediately assumed the crash had something to do with the kind of flying he did, but it turned out that they found a lot of water in his fuel and fuel source. So there was a pretty good chance he was using contaminated fuel and that it caused an engine failure in flight. Is that his fault? I have to argue that it is — isn’t checking the fuel part of our pre-flight? To write it off as bad luck is disregarding the fact that the pilot could have prevented the crash by simply testing the fuel before taking off. You can bet that I test my fuel a lot more often now.

I read a lot of helicopter accident reports and recommend that other pilots do the same. Learn from other people’s mistakes! The more accident reports you read, the more mistakes you can learn about. Maybe this is why I don’t give the pilot the benefit of the doubt in most accidents. I know how they (we!) can screw up.

Reading through accident/incident reports is both educational and a good reminder. Regardless of how many different contributory factors are brought up, they nearly always lead to the conclusion that the root cause is human error. Overconfidence, complacency, laziness, ignorance, poor judgement, sometimes all of the above.

When you look at the metadata on helicopter accidents, there is an slight but unmistakable reverse bell curve related to the experience level of the pilots involved. As expected, the accident rate is highest at low pilot experience levels. Also as expected, it decreases as pilots gain gain flight hours and experience. The unexpected part is that it slowly starts to increase again for pilots with 4000-5000 hours stick time. The study I saw on this subject was specific to helicopter EMS flying, but I suspect it applies to all specialties. Poor judgement and overconfidence gets the new pilots, but complacency and laziness can also trip up the old hands.

The insidious thing about human error is that we all develop our own blind spots when it comes to the errors that we make. The natural human tendency is to to overvalue our own personal experience and overlook our own flaws, while disregarding and dismissing criticism and negative feedback from others. It takes consistent, conscious effort to keep an open mind to our own flaws and shortcomings, which is rarely a pleasant process. Necessary, but uncomfortable, if you wish to avoid repeating both your own mistakes and duplicating those of others.

I’ll never forget one of my own personal screw ups with complacency. While working an EMS contract I took a longish VFR night flight to a remote rural hospital, refueling for the return flight at a nearby private airport that had a card-lock fuel setup. After parking it on the hospital roof and partially refueling (we never left it with a full tank due to the density altitude) I went to bed instead of waiting an hour and taking a fuel sample like I was supposed to by our procedures manual. The day shift didn’t fly at all, and at the regular weekly pilots briefing the next night our lead pilot casually asked if I’d checked a fuel sample after gassing up at the remote location.

I waffled, I couldn’t remember if I had gone back before shift change or not. He then brought out a quart jar of what looked like cowboy coffee; oily, dark brown, and chock full of particles that looked exactly like coffee grounds. They’d spent most of the day draining and pulling samples, changing filters, the whole works. I was taken aback, since our rooftop fuel checked out fine it was obviously the fuel I’d picked up at the card lock pump. And then flown home with, over the mountains, in the dark. We took that fuel location off our approved list, especially seeing as the operator didn’t think it was a big deal and didn’t particularly seem to care. It was a real wake-up call for us all, but particularly for me. Never again will I take the lazy way out when it comes to fuel samples, especially from a location where I don’t control the quality checks.

Respect for your honesty. One question Sean. Was the fuel you picked up on the night flight so polluted it could have blocked the filters and stopped the engines, had the flight been longer?

The incident I find most instructive is BA 762, London to Oslo, (5/24/2013). Two engineers work on the engines of an Airbus 319 in the company hangar. They sign off on the work.

They fail to secure either of the engine cowls. The next morning the flight crew also fail to notice the unlatched cowls in their walk around check. At 200 kts the cowls blow off and one ruptures a line and causes a starboard engine fire. They call Mayday and land safely. But four people, doing a basic check, failed to see a potentially very serious fuster cluck.

Could the bad fuel have blocked the fuel lines? No way to know, though I suspect it could have been so. This is one situation (refueling at a remote location) where every pilot has to trust that the supplier has done their part as regards quality control checks. In most places nearly every aviation fuel seller does so very conscientiously. They are motivated by their professionalism, to preserve their business and its reputation, and in the U.S, the ever-present threat of a lawsuit.While water contamination settles very quickly in a tank of avgas (6 lbs/gallon vs. 8 lbs/gallon), it is far slower to find its way to the drain sumps in a tank of jet fuel. Not only is jet fuel much closer to the density of water, (6.8 lbs/gallon) but fungal growth can cause the water to emulsify into very fine droplets when mixed by the pump, which are slower to coalesce and collect at the low points in the tank. The nature of aviation (and particularly helicopter EMS) is speed, so waiting an hour after EVERY refueling in order to take a sure sample is not in the cards. You can take a quick sump after every fill-up, but without that wait time you will never really find out what is in the tank. You have to trust your fuel suppliers to do their job right, but it is the pilot and passengers/flight crew that assume the risk if they don’t. .

Thanks for that full explanation Sean.

I have just read about the power loss and subsequent crash of a Eurocopter Lama C-FJJW

(Operated by Turbowest) in Jan 2000 in BC. In this incident the water filter seems to have denatured and formed amber ‘cellulose’ deposits which narrowed the injection tubes.

“temporarily unaware of exact position”…HA !!!

That describes nearly my entire career flying VFR in helicopters. And as my Army instrument instructor would probably say, a fair amount of my early IFR training flights as well!

Nearly all of my flight time in the military was flown using only the HHM for navigation, the Hand Held Map. This was in the era prior to GPS, when a single VOR in a Cobra gunship was the height of navigational luxury. The erratic and often dysfunctional ADF receiver was the default navaid, sometimes in addition to a Doppler “Navigation” unit that was really more useful for the aiming computer than it was for nav.. As anyone who has “relied” on an ADF would tell you, they made far better AM radios than they did navaids. In my later civilian flying career we used mostly LORAN with a scabbed-on GPS patch unit; only towards the end did GPS become the default.

In any case, for VFR you rarely NEED to know your exact position at all times, a rough approximation works for most everything except takeoff and landing, provided you know your position well enough to stay clear of trouble spots like Prohibited Areas and such.

To Maria and Sean.

Re: your interesting posts, above.

You are both right. Aviation is an inherently risky business. Pilots are paid to defy gravity and gravity is a powerful force, as anyone who has missed a step going down a staircase knows. Pilots train to overcome, and return to, the harsh rule of gravity with smoothness and control. They try to measure and minimise risk.

Sean has military experience and in parts of that realm a cautious pilot might be safe but not useful.

In the book ‘Chickenhawk’ the author, Robert Mason, describes using the rotor of his Huey (Vietnam era) as a brush-cutter to create his own landing pad in thick vegetation, to pick up his buddies. He did it, it was a mad action.

In 1940, RAF fighter pilots fought better-trained German pilots, over their English homeland and won. Yet the cost was very high. Of the roughly 2,000 British fighter pilots in that brief 14 week battle, only 10% survived to the end of the war. Military flying is a risky business. Erich Hartman, a ‘natural’ pilot and the supreme air-ace for all time, crashed many times.

In a civilian context, every accident is considered a mini disaster, yet some of these are not due to ‘gungho’ heroics, or rash stupidity, but the very opposite. Take the loss of Air France flight 447. Three well-qualified pilots, flying an Airbus from South America to Paris, over-flew a tropical storm and all their pitot heads froze-over at 35,000 feet and thus, with no data on airspeed, their auto-throttle cut power and they entered a high speed stall with wings level and nose up. With a combined 40 years of commercial flying experience none of these pilots thought to do what any 10 hour trainee would have been told to do: “stick forward to break the stall, regain airspeed and flying control, add power”. They had surrendered the control of their aircraft to its computers, which eventually fell silent.

After four minutes of intense flight-deck debate the aircraft hit the Atlantic Ocean, still in the stall configuration, and everyone died. A wholly avoidable loss of an undamaged aircraft.

Since then Air France training has been changed and airliner pitot heads no longer freeze over, even in the most extreme conditions But that accident is salutary. And as you say Maria, we learn much from them.

I don’t know a single pilot you has never flown in conditions where one or more of the following has applied:

Over-weight for density altitude.

Landing which exceeds published crosswind limits.

(Briefly) Flying VFR in IMC.

Forgetting one or more walk-around or pre-flight checks.

Under-fuelled for a flight which might require a hold or diversion.

Flying with unsecured baggage.

Pressing on with a flight as met. conditions deteriorate.

Being ‘temporally unaware of exact position’.