A comedy of errors in four acts.

I’m at Bryce Canyon this morning. I flew up here with a client to do an aerial photo shoot. We knew the weather was going to get bad today and made sure we arrived yesterday, before we couldn’t get in at all. Based on the forecast, we figured we’d get the shoot done on Sunday afternoon and Monday morning before heading down to the Grand Canyon to do a shoot there.

The weather was surprisingly good and, if it hadn’t been so windy, we probably would have attempted the shoot on arrival. Instead, we parked the helicopter and I slipped on its blade hail covers, which I’d brought along. We’re not expecting hail, but I figured (correctly, according to two cold-climate pilots I spoke to) that the covers would also keep snow and ice off the blade surfaces. Unfortunately, there was no way to guarantee that snow wouldn’t accumulate on top of the covers. Heavy snow or ice sitting on the covers on the blades could cause them to droop excessively; if that happened, the blade droop stops could be damaged. So I’d have to keep an eye on the situation, possibly by making multiple trips to the airport during the weekend. The airport is 3 or 4 miles from the hotel we’re staying in, Ruby’s Inn. My client rented a car.

After checking in at Ruby’s the weather got better and better. My client went into the park to photograph the hoodoos and stayed there to watch the moon rise. He told me later that he took 20-minute exposures of the hoodoos lighted by just the moon and they look like they were shot in daylight. (I’m looking forward to seeing them.) I elected to stay in my room. I’m recovering from a nasty cold that just about ruined my vacation. It was cold out — probably around 35°F before sunset — and the heater works very well in my room. When I finally turned in for the night around 9 PM, the moon was shining brightly in what looked like a perfectly clear sky.

Hard to believe the weather forecast said 80% chance of snow in less than 2 hours.

Act I: The Snow Begins

Things were different when I woke up at about 3:40 AM. There was probably about 2 inches of snow on the ground and more coming down. Two hours later, when it started to get light, there was at least another 2 inches. Not much wind, either. I started wondering how much 4 inches of snow on 14-foot long helicopter rotor blades weighed.

At about 7 AM, my client showed up outside my door. I saw him through the window; he didn’t want to knock. I opened it. By then, the snow was quite impressive, piled up on everyone’s car. The wind had begun to blow a bit, too.

“Look at all this snow,” he said. “We can’t go to the airport to check the helicopter. The car is just a sedan. No four wheel drive.”

In all honesty, it didn’t look that bad yet. I recall driving 40 miles in snow twice as deep — in a 1987 Toyota MR2. Not exactly an all-terrain vehicle.

I told him I’d call the airport. I did. No one answered. I left a message asking them to peek out the window and report back to me about the rotor blades. But at the rate the snow was falling, I wasn’t willing to wait long for a report. I told my client I’d try again in a half hour. Otherwise, I needed to go.

The snow kept falling. The wind was blowing but didn’t seem to be making a dent in the accumulations on the tops of cars and trucks parked silently in the lot below my window.

Act II: Our Drive to the Airport — and Confrontation with a Jerk

At 7:30, after getting no answer at the airport again, I got dressed in my best effort at winter gear. That meant a cotton turtleneck shirt with a cotton long sleeved shirt over that, a pair of nylon/spandex leggings with a pair of denim jeans over that, cotton socks, sneakers (I left from Phoenix where I don’t keep a pair of boots), my wool scarf, my leather jacket (with lamb fleece collar removed so as not to gather snow), ear warmer head band, baseball cap, and wooly gloves. The only pieces of clothing from my suitcase that I wasn’t wearing were my pajamas, the shirt I’d worn the day before, and one extra shirt I’d brought along. I looked ridiculous (see photo; I don’t think putting this photo on Craig’s List would get me in as much trouble as this guy’s photo did) but figured I’d be warm enough.

At 7:30, after getting no answer at the airport again, I got dressed in my best effort at winter gear. That meant a cotton turtleneck shirt with a cotton long sleeved shirt over that, a pair of nylon/spandex leggings with a pair of denim jeans over that, cotton socks, sneakers (I left from Phoenix where I don’t keep a pair of boots), my wool scarf, my leather jacket (with lamb fleece collar removed so as not to gather snow), ear warmer head band, baseball cap, and wooly gloves. The only pieces of clothing from my suitcase that I wasn’t wearing were my pajamas, the shirt I’d worn the day before, and one extra shirt I’d brought along. I looked ridiculous (see photo; I don’t think putting this photo on Craig’s List would get me in as much trouble as this guy’s photo did) but figured I’d be warm enough.

I went to my client’s door. He was wearing sweatpants, having a cup of coffee. He didn’t look ready to go out. I told him I’d start scraping the snow off the car. He protested quite loudly, but I just went.

I had a plastic shopping bag with me and I used it to cover one arm. (The goal was to keep as dry as possible.) I then used sweeping motions to get the snow off the car. It didn’t take long. The snow was a bit wet but moved easily. Not very heavy. But there was at least 8 inches of it accumulated. What would that weigh on my blades? I was starting to get very nervous about it.

I had a plastic shopping bag with me and I used it to cover one arm. (The goal was to keep as dry as possible.) I then used sweeping motions to get the snow off the car. It didn’t take long. The snow was a bit wet but moved easily. Not very heavy. But there was at least 8 inches of it accumulated. What would that weigh on my blades? I was starting to get very nervous about it.

A plow came through the parking lot leaving the inevitable snow bank behind the car.

My client appeared. He told me he was going to buy an ice scraper. I pointed out that there wasn’t any ice. I asked him to start the engine and use the wiper blades to finish off the front window. I recleared the side and back window; another 1/4 inch of snow had already blanketed them.

While he backed up, I stood at the hood, pushing. He didn’t seem to have much trouble moving it, but made the fatal error of turning the wheel before he’d cleared the snowbank. The back end of the car plowed into it and the car was stuck fast.

I started work on the snowbank. By this time, two other cars had successfully extracted themselves. Two guys hurried over to help us. When the car wouldn’t budge, one asked if he could sit at the wheel. My client stepped out and the other guy got in. With three of us pushing at the hood and the driver’s good “rocking” skills, the car was soon extracted. I asked if we could help them with their car and they assured us that wasn’t necessary. They had four-wheel drive.

My client wound his way through the plowed area of the parking lot and into the main road. He was not a happy camper. But the road didn’t seem slippery, and at our slow speed, we weren’t sliding around at all. The main trouble was seeing the road. Everything was white and the road surface perfectly matched the white snowbanks on either side. Visibility was probably about 1/4 mile. The airport’s weather system was reporting freezing fog and now I knew what that looked like.

When we reached the junction of Highway 12, we stopped. There was no one around us in any direction. From inside the car, it was impossible to see if the road had been plowed at all. So I got out to take a look. It had been plowed, but not recently. It had tire tracks on it. It looked doable.

But before I could begin convincing my client/driver to continue on, a beat up old pickup truck made the turn onto our road. Because we were stopped in the middle of the road, he pulled in on our right side, facing into incoming traffic (if there had been any). He got out and told us we needed to be off the road. The conversation went something like this:

Him: You need to get off the road.

Me: We’re just checking road conditions. We’re going to the airport.

Him: Do you know where that is?

Me: About a mile or two that way. (I pointed into the whiteness of Route 12.)

Him: You need to turn around and go back.

Me: We can’t turn around here.

Him: Then I’ll call a tow truck.

Me: We don’t need a tow truck. We’re not stuck.

Him: Then I’ll call the sheriff.

Me: Why?

Him: You need to get out of the road.

Me: We will. We’re just looking at the road conditions before deciding what to do.

Him: I’ll call the sheriff.

Me: [exasperated and tired of maintaining a pointless conversation with a self-important moron] Go ahead.

Meanwhile, my client was beginning to freak out. He’s not American born and although his English is good, I don’t think he was able to keep up with our rapid-fire exchange. He did, however, hear the word sheriff twice, and he assumed we’d done something serious enough to possibly get arrested.

Him being freaked out wasn’t helping matters. He already was worried about continuing on the road. Now we had this jerk partially blocking our car, talking to someone on his cell phone. I needed to get to the airport. I knew it was possible. I had to convince my client. Finally, all I managed to do was convince him to let me drive. But the jerk was still blocking us. Tooting the horn had no affect.

That’s when I got pissed off.

I got out of the car and walked around to his window. I could tell by his uniform shirt that he worked for a gas station or something. I asked him where he worked and he said he worked for the tow truck operator across from our hotel. (Figures.) I told him I didn’t like his attitude and would be talking to his boss. He held the phone out so whoever was on it could hear me and I repeated loudly at the phone, “Your attitude sucks and I’ll talk to your boss about it.” I started to walk away, but then turned back and said, “Now get the fuck out of our way.” (Once a New Yorker, always a New Yorker.)

As I walked away, he got back out of the truck and started shouting at my back. “Well, I’m also the fire chief in [redacted] and on the EMT team and — ” I didn’t hear the rest. I was already in the car with my door closed. He, of course, didn’t move. Instead, he made a big show of walking behind the car, apparently to get our license plate number, further freaking out my client. I had to carefully make my way around his piece-of-crap truck, avoiding the deep snow bank on my left as well as I could. Then I made the left turn onto Route 12 and headed toward the airport.

The going was easy. But what really surprised me is that the airport road was plowed. The only problem was the snow bank from our road to that one. So we got out, leaving the car in the middle of the deserted road, and worked on it. I discovered that a floor mat, when wielded by two people, works very well as a scraping shovel. I turned the corner and saw a big front-end loader coming toward us. The airport guy was using it to plow the road. We stopped and talked to him. He said there wasn’t much snow at all on the helicopter. Then he told us where we could turn around safely past his house down the road.

We continued to the airport and were very surprised to see that there was hardly any snow on the helicopter at all. The wind was doing all the work for me. All those worries for nothing. We stopped and talked to the airport guy again. He volunteered to keep an eye on the helicopter and clear snow off it needed. He was a good, reliable, friendly guy. I felt all my worries fade away as we said goodbye and headed back to the hotel.

Act III: Black Ice

If you’ve ever driven in fresh snow, you might know that some snow is actually quite easy to drive in. It’s the stuff that’s not too wet and not too dry. It packs under your tires as you drive but doesn’t turn to ice in the process. That’s what we’d been driving on until we got to the airport road.

The airport road, however, was freshly plowed. Maybe it was the sight of that clean black pavement on the road in front of me that gave me the confidence I needed to drive at 20 miles per hour rather than a more conservative 10 or 15. Unfortunately, what I didn’t realize is that I wasn’t looking at pavement. I was looking at the half-inch layer of solid, smooth ice that sat on top of it.

Black ice.

There’s a tiny bend in the airport road before you reach Route 12. It’s so slight, it doesn’t even show up on a map. As I turned the wheel to the left to make this bend, the tires started to skid. My client reacted by saying the appropriate frightened passenger words. I pumped the brakes gently and, for a second, had it under control. Then more skidding and more right seat panic. My brain shut off and my foot pressed the brake down hard. Then it was all over.

In slow motion, the car skidded nose first into the snow bank on the right side of the road.

In slow motion, the car skidded nose first into the snow bank on the right side of the road.

Shit.

It was stuck good. I couldn’t even get it to move an inch in either direction. The front wheel drive tires were sitting right on some of that black ice and all they could do was spin. We worked on it for a good ten to fifteen minutes, even putting the floor mats behind each tire in case it moved. No joy. And I do mean that literally.

We retreated into the car where I tried to get the airport guy on the phone. He didn’t pick up his cell. I called another number on the airport’s voice mail message system and reached a guy in Las Vegas. He was the airport guy’s boss. He said that he was out on the plow (which I knew) and probably couldn’t hear the phone ring. I told him our predicament. He told me to call 911. I said, “No, this isn’t an emergency. We’re in a warm car with plenty of gas within sight of Route 12. One way or another, we’ll get out without emergency assistance. Let them take care of heart attacks and accidents.” I think he was surprised by my take on 911. I asked him to mention us to the airport guy if he happened to call back.

I thought about calling AAA and realized that they’d likely call the jerk I’d cussed at and he’d likely not come. (Yeah, yeah, save the lectures.)

I started walking back toward the airport while my client yelled at me to stay in the car. I had to slip and fall twice on that damn black ice before heeding his words.

I tried the airport guy a few more times. On the third time, he answered. I told him our predicament. He told me he’d be right out. I told him to take his time. Warm up, have some coffee. We could wait. My client agreed. “Bring a shovel, though,” I added.

He showed up about 15 minutes later with his big front-end loader and turned it around so its back end faced the back end of our car. Then we hunted around for a place to tie onto the car. In the old days, imports — this was a Mazda — had these loops on the front and back of the car to tie them down during the boat ride from Japan. This one didn’t have those. But he found a loop on the frame. Trouble was, his chain wasn’t long enough to reach it.

He climbed back into his rig. By that time it was snowing very hard and the wind was blowing it almost horizontally. When he came back, he told me he’d made some calls and couldn’t get chain long enough to do the job.

“What do you think our options are?” I asked him.

“Well, I called the rental company for you and they said they could send a tow truck for $45.”

I’d already told him about our confrontation with the jerk. “The same tow company that guy I had a fight with works for?”

“I can ask them not to send [redacted jerk’s name],” he promised, grinning at me.

“Then do it,” I said. “I’ll pay $45. Cash if they want it.”

He made the call. I overheard him say, “You have to send [redacted jerk’s name]?” and I said, “I’ll pay $75 if they don’t.” He laughed and said, they’re just pulling your leg.

Call done, he told us to wait in the car. My client had been shoveling snow the whole time. I told the airport guy to go back and we’d be okay. He said he’d stick around just in case [redacted jerk’s name] showed up. I offered to let him wait with us in the car, but he preferred the backhoe.

We got back in the car. My client was really freaked out by the snow accumulation and the prospect of driving back to the hotel. That surprised me because he lived in Chicago and was no stranger to snow. But he told me that at home he had a truck with some sort of special snow driving gear. I didn’t get the details, but it seemed that he was convinced such special equipment was required for driving in the snow.

Whatever.

I just felt like an idiot for skidding into the snow bank and getting stuck. I know nothing had been damaged other than my pride, but I resolved to rent my own car on any future trips to shield my clients from the consequences of my stupidity.

Act IV: The Happy Ending

The tow guys showed up a while later and [redacted jerk’s name] was not among them. One of them asked me if I was the one [redacted jerk’s name] had a fight with. I admitted I was and we all had a good laugh. It took some work to get the car out and all three of the guys helping us nearly fell on their butts because of the damn black ice. Every single time one of them slipped, they’d comment on it. It was really nasty stuff. When the car was out, they said they’d be just as happy if we paid via AAA — in other words, making it a free tow — and urged us to do so. That worked for me.

I told the airport guy that I owed him big time but he insisted we were even. Even? How? I hadn’t done him any favors. At least not yet. I’ll think of something and if I don’t come up with a good one, I’ll leave my friend Ben Franklin on his desk before I fly out on Monday.

My client drove back with me pointing out the road. He was still having trouble seeing it. The tow guys followed us. We went into the gas station where my client took care of paperwork. He told me he would put it on his AAA, but he wound up paying instead, worried that he’d need the tow again later in the day and knowing that AAA doesn’t respond twice in one day. (I’ll put a $45 credit on his bill for this job.) I slipped each of the tow guys $10 in plain sight of [redacted jerk’s name] who appeared outside as we arrived, apparently looking for sunglasses left in their truck. We all ignored him. (In real life, as in online forums, the best policy is usually to ignore the assholes.)

Meanwhile, my jeans were completely soaked and I was starving. My client and I went into Ruby’s for breakfast. While we waited for coffee, he urged me to check out the boots they had available in the adjacent store. I went into the store, but instead of looking at the boots, I found a pair of sweatpants. I used the fitting room to peel off my jeans, surprised that the leggings beneath them were dry. I put on the sweats and went right to the cash register, picking out a pair of socks on the way and carrying my wet pants and newly washed sneakers. “I’m buying these now,” I told the cashier, reaching into the back and pulling the price tag off. We had a good laugh as she rung me up. It was the first time I’d ever spent $16 on a pair of socks, but desperate times require desperate measures. I was back at the table before my coffee was cold and received the scolding delivered by my client because I’d come back without new shoes.

I changed my socks while my client was outside having a smoke and I was at the table waiting for our meals.

Breakfast was typical Ruby’s. I’d like just once to get a good meal with good service there.

My client dropped me off at my room before venturing into the park. Visibility is so low that I think it’ll take quite some time for conditions to improve enough for photography. But that’s what he’s here for.

Me, I’m just along for the ride until it’s time to fly.

And yes, I’ll keep my hands off his rental car.

So instead of giving my guests their Phoenix Tour and heading up the Verde River on Day 1, we took a shorter route to Sedona that overflew Lake Pleasant and stayed within several miles of the I-17 corridor. I figured I’d save the scenic flight for when visibility was better. I also expected visibility to be better in the Sedona area and was very surprised that it was not.

So instead of giving my guests their Phoenix Tour and heading up the Verde River on Day 1, we took a shorter route to Sedona that overflew Lake Pleasant and stayed within several miles of the I-17 corridor. I figured I’d save the scenic flight for when visibility was better. I also expected visibility to be better in the Sedona area and was very surprised that it was not. The flight to the Grand Canyon on Day 2 wasn’t anything special — except for that white haze that persisted, even up on the Coconino Plateau. Very odd for Arizona. It wasn’t blowing dust, either — the wind wasn’t strong enough for that. Just an ugly haze.

The flight to the Grand Canyon on Day 2 wasn’t anything special — except for that white haze that persisted, even up on the Coconino Plateau. Very odd for Arizona. It wasn’t blowing dust, either — the wind wasn’t strong enough for that. Just an ugly haze. Day 3 dawned gray but with plenty of visibility. I even got out and snapped a few photos when the sun poked through some clouds and illuminated one of the rock formations in the canyon near Bright Angel Lodge, where we were staying. I grabbed some coffee, went back to my room, and checked e-mail. An hour later, I peeked out the window and saw that it was snowing.

Day 3 dawned gray but with plenty of visibility. I even got out and snapped a few photos when the sun poked through some clouds and illuminated one of the rock formations in the canyon near Bright Angel Lodge, where we were staying. I grabbed some coffee, went back to my room, and checked e-mail. An hour later, I peeked out the window and saw that it was snowing. I felt bad for my guests. They’d spent a lot of money on this trip and now they were stuck at a scenic place with no scenery and no helicopter flight to get them to their next destination. So I became their driver for the day. After realizing that the truck was not likely to make it to Desert View (on the east end of the park) before the roads were cleared, we stopped at the Visitor Center and the Geology Museum before heading into Tusayan (the tourist town outside the park) for lunch. The plan was for them to see the IMAX movie across the street next.

I felt bad for my guests. They’d spent a lot of money on this trip and now they were stuck at a scenic place with no scenery and no helicopter flight to get them to their next destination. So I became their driver for the day. After realizing that the truck was not likely to make it to Desert View (on the east end of the park) before the roads were cleared, we stopped at the Visitor Center and the Geology Museum before heading into Tusayan (the tourist town outside the park) for lunch. The plan was for them to see the IMAX movie across the street next. But that plan failed miserably. When I got to the airport, I found the helicopter’s right side — the side facing the weather — completely iced over. The main rotor hub, the tail cone, and the tail rotor were all coated with ice. Even the skids looked frozen to the ground. And, of course, there was a good helping of snow in the fan scroll (again!) and even some inside the air intake port. The temperature had dropped by 10°F and it was now below freezing. It would not warm up again that day. The helicopter was officially grounded.

But that plan failed miserably. When I got to the airport, I found the helicopter’s right side — the side facing the weather — completely iced over. The main rotor hub, the tail cone, and the tail rotor were all coated with ice. Even the skids looked frozen to the ground. And, of course, there was a good helping of snow in the fan scroll (again!) and even some inside the air intake port. The temperature had dropped by 10°F and it was now below freezing. It would not warm up again that day. The helicopter was officially grounded. I wound up driving them to Page. The trip should have taken just over 2 hours, but since the weather was clearing enough to see into the canyon, we made several stops along the way. We arrived in Page at 8 PM. I checked them into their room, made sure they were set for the next day’s boat ride, and checked into my room at the Day’s Inn.

I wound up driving them to Page. The trip should have taken just over 2 hours, but since the weather was clearing enough to see into the canyon, we made several stops along the way. We arrived in Page at 8 PM. I checked them into their room, made sure they were set for the next day’s boat ride, and checked into my room at the Day’s Inn. Now what I needed was a thaw — temperatures above 32°F. I must have called the AWOS number for GCN a dozen times before 10:30 AM on Day 4. Then I climbed into my redneck truck and made the trek down to Grand Canyon Airport. It took 2 and a half hours with just one stop to snap pictures of a very different (from the previous day) view.

Now what I needed was a thaw — temperatures above 32°F. I must have called the AWOS number for GCN a dozen times before 10:30 AM on Day 4. Then I climbed into my redneck truck and made the trek down to Grand Canyon Airport. It took 2 and a half hours with just one stop to snap pictures of a very different (from the previous day) view. The flight was, for the most part, smooth. I ran the video camera (as you might expect) and captured some good footage over the Little Colorado River Gorge and along the Echo Cliffs. I set down on a helipad at Page Municipal Airport at 3 PM.

The flight was, for the most part, smooth. I ran the video camera (as you might expect) and captured some good footage over the Little Colorado River Gorge and along the Echo Cliffs. I set down on a helipad at Page Municipal Airport at 3 PM.

My client steered us to Sunset Point. Two very large snow throwers were at work in the parking area where only two cars were parked. We parked behind one of them, got our gear together, and headed out to the lookout point.

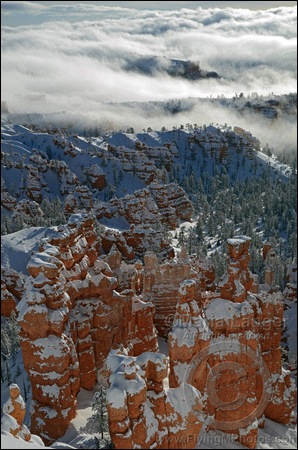

My client steered us to Sunset Point. Two very large snow throwers were at work in the parking area where only two cars were parked. We parked behind one of them, got our gear together, and headed out to the lookout point. The first hint that things might improve came a while later when the sun started breaking through the clouds. I snapped this photo using the HDR function of my iPhone and then fixed it up a bit more in Photoshop to bring out the shadows. Not too impressive. The light faded again right after that and I started thinking about how warm the car might be. But I decided to stick it out a bit longer.

The first hint that things might improve came a while later when the sun started breaking through the clouds. I snapped this photo using the HDR function of my iPhone and then fixed it up a bit more in Photoshop to bring out the shadows. Not too impressive. The light faded again right after that and I started thinking about how warm the car might be. But I decided to stick it out a bit longer.

At 7:30, after getting no answer at the airport again, I got dressed in my best effort at winter gear. That meant a cotton turtleneck shirt with a cotton long sleeved shirt over that, a pair of nylon/spandex leggings with a pair of denim jeans over that, cotton socks, sneakers (I left from Phoenix where I don’t keep a pair of boots), my wool scarf, my leather jacket (with lamb fleece collar removed so as not to gather snow), ear warmer head band, baseball cap, and wooly gloves. The only pieces of clothing from my suitcase that I wasn’t wearing were my pajamas, the shirt I’d worn the day before, and one extra shirt I’d brought along. I looked ridiculous (see photo; I don’t think putting this photo on Craig’s List would get me in as much trouble as

At 7:30, after getting no answer at the airport again, I got dressed in my best effort at winter gear. That meant a cotton turtleneck shirt with a cotton long sleeved shirt over that, a pair of nylon/spandex leggings with a pair of denim jeans over that, cotton socks, sneakers (I left from Phoenix where I don’t keep a pair of boots), my wool scarf, my leather jacket (with lamb fleece collar removed so as not to gather snow), ear warmer head band, baseball cap, and wooly gloves. The only pieces of clothing from my suitcase that I wasn’t wearing were my pajamas, the shirt I’d worn the day before, and one extra shirt I’d brought along. I looked ridiculous (see photo; I don’t think putting this photo on Craig’s List would get me in as much trouble as  I had a plastic shopping bag with me and I used it to cover one arm. (The goal was to keep as dry as possible.) I then used sweeping motions to get the snow off the car. It didn’t take long. The snow was a bit wet but moved easily. Not very heavy. But there was at least 8 inches of it accumulated. What would that weigh on my blades? I was starting to get very nervous about it.

I had a plastic shopping bag with me and I used it to cover one arm. (The goal was to keep as dry as possible.) I then used sweeping motions to get the snow off the car. It didn’t take long. The snow was a bit wet but moved easily. Not very heavy. But there was at least 8 inches of it accumulated. What would that weigh on my blades? I was starting to get very nervous about it. In slow motion, the car skidded nose first into the snow bank on the right side of the road.

In slow motion, the car skidded nose first into the snow bank on the right side of the road. The helipad is a 75-foot square of concrete, marked with a big, white, reflective cross in the middle. Around that is another 20-25 feet of big, dust-free gravel. A four-foot fence surrounds the whole thing (see red box). Access is from the street side only, where a double gate can open to admit an ambulance. A concrete path leads up to it so pedestrians don’t need to walk on the gravel.

The helipad is a 75-foot square of concrete, marked with a big, white, reflective cross in the middle. Around that is another 20-25 feet of big, dust-free gravel. A four-foot fence surrounds the whole thing (see red box). Access is from the street side only, where a double gate can open to admit an ambulance. A concrete path leads up to it so pedestrians don’t need to walk on the gravel. This photo shows my arrival and departure paths with a few points of interest.

This photo shows my arrival and departure paths with a few points of interest. Let’s do some pilot math here through the use of a density altitude chart. At 3,000 feet elevation with an outside air temperature of 35°C (roughly 95°F), the density altitude is about 6,000 feet. That means my aircraft would perform as if I were taking off and landing at a helipad at 6,000 feet elevation rather than 3,000 feet.

Let’s do some pilot math here through the use of a density altitude chart. At 3,000 feet elevation with an outside air temperature of 35°C (roughly 95°F), the density altitude is about 6,000 feet. That means my aircraft would perform as if I were taking off and landing at a helipad at 6,000 feet elevation rather than 3,000 feet. I guess the easiest way to explain it is that the OGE hover chart is the best indicator of the most power I’ll have in the worst possible condition. It takes more power to hover than to fly and it takes more power to hover OGE than IGE. So if you want to know what the maximum performance is in a worst case scenario situation, consult the OGE chart.

I guess the easiest way to explain it is that the OGE hover chart is the best indicator of the most power I’ll have in the worst possible condition. It takes more power to hover than to fly and it takes more power to hover OGE than IGE. So if you want to know what the maximum performance is in a worst case scenario situation, consult the OGE chart.