One reason it’s so hard for small companies to get ahead.

The other day, I got another call from XYZ Company. That’s not their real name, of course, but it’ll do for this article.

XYZ has been calling me occasionally for the past four years. It’s a tour packaging company based in the eastern United States. But it doesn’t sell itself as a packager. Instead, its ads lead clients to think that it’s a huge tour company with offices all over the country.

How does it do this? By advertising the services of small companies like mine, Flying M Air, as its own.

Now I don’t want to say that they are deliberately misleading the public. I’m sure the ads have fine print somewhere that makes it clear that they are not providing the services. After all, I’m sure they don’t want any liability if something should go wrong. And I’m pretty sure that if a client asked straight out who would be providing the services, they’d admit that they used subcontractors. But I’m equally sure that the client would have a difficult time finding out exactly who was providing the services until they had paid for them.

What They Do

Here’s how it works. XYZ calls me to ask whether I can perform a specific tour or other helicopter charter service. When I say that I can, they ask about my rates. I give them an hourly rate. They then go into some detail on exactly what they’re looking for and ask whether I can do it.

Mine sites can be tight to land in. I’d be hard-pressed to fit my helicopter in here.

In some (few) cases, the job is simple: a helicopter flight from point A to point B in my area. But in many cases, the job is more complex. A recent job query, for example, would require me to fly to a location about 100 miles from my base and spend three days there. While there, I’d take two passengers over some nearby mines they apparently own, landing if requested so they can get out and do mining-related stuff on the ground. Then, if they need help, I’d go back and fetch two companions and bring them to the site. I’d then wait around for them to be ready to move on and shuffle them to the next site.

As you might imagine, this isn’t as simple as quoting an hourly rate. I have to get compensated for the trip from my base to the client location and back and the cost of spending the night away from home. I also need to get a minimum number of hours of flight time each day to make it worth keeping my helicopter unavailable for other work.

I get calls like this from people quite often. Not exactly this scenario, of course, but other work that’s equally weird and/or time-consuming. In so many cases, the callers clearly have no idea about the cost of using a helicopter for their task. They figure they’ll need about three hops from point to point and that surely can’t take more than an hour or two. They don’t see the ferry time (three hours, in this case), the overnight fees (at least $250 per night), or the need for daily minimums. They think I’m going to provide them with three days of service, putting my aircraft at their whim, for the cost of two hours of flight time. As you can imagine, I don’t do much of this work.

In this particular case, it took two phone calls (so far) to discuss the job and an argument about how long it would take me to fly from my base to the client’s. I’ve underestimated ferry flight time enough times to know that it’s better to overestimate and be able to charge the client less than he expects. The project is still in limbo, but I don’t expect it to happen. In most cases, a call from XYZ means nothing more than time wasted on the phone.

Dealing with a Middleman

There are two differences between dealing directly with a client looking for a quote and dealing with the telephone jockeys at a middleman company like XYZ:

- The client knows exactly what he wants. He tells me, I ask questions, he answers them. Within a few minutes on one phone call we zero in on a complete description of the job and a pretty solid estimate of costs. This results in sticker shock for the caller, an agreement that we can’t work together, or a tentative reservation. The telephone jockeys for companies like XYZ, on the other hand, have very little idea of what the client wants or needs or the kinds of services a helicopter operator can provide. After all, the last call they took was for a boat ride around Manhattan or a train ride to Denali or a bus tour to the Grand Canyon. They get just the basic client needs, search their database for possible providers in an area, and call a company like mine. They don’t know anything about my aircraft or its capabilities. Not only do they not know answers to my questions — how much flight time per day? do they own the land I have to land on? how much does each passenger weigh? are they carrying equipment? is there any flying time at night? are the mines anywhere near the restricted areas in that part of the state? — but they don’t know what questions to ask me on behalf of the client. They are middlemen. As a result, most queries take more than one phone call.

- Companies like XYZ need to make a profit. Rather than be satisfied with a commission that I’m willing to pay, they jack up my rates and charge that to the client. How much do they add? In the one instance I was able to discover the rate they charged a client, it was 30%. So my clients are paying a 30% premium for my services when they book with a company that has no clue about the kind of services I offer. As a result, companies like XYZ often price me out of the market. I don’t get the work because I cost too much. But those aren’t my prices. They’re they premium prices charged by XYZ. What pisses me off the most is that my margins are so thin that XYZ would likely make more money on a job than I would — and I’m the one doing the work.

In the past four years, I’ve been contacted about a dozen times by XYZ. Occasionally, I get a telephone jockey who seems to know what he’s doing. But in most cases, the guy calling is pretty clueless and I have to list the questions I need answered to provide a quote. I almost got work with XYZ twice.

They Promise Services I Can’t Deliver

Meteor Crater is amazing from the air, but don’t expect me to land inside it.

Once, a UK-based television company wanted to get some aerial footage of Meteor Crater in northern Arizona. What a lot of people don’t know is that Meteor Crater is privately owned. The whole damn thing is on someone’s property. They’ve put in a very nice museum and walkways to overlook the crater. It’s a cool place to visit and I highly recommend it, especially if you have kids interested in space.

The best views, however, are from the air. Television people know this. They wanted to hire me to take them around the crater and get footage. At least that’s what XYZ told me.

It took three or four phone calls to get the information the client and I needed to make sure we were on the same page. We agreed on rates and times and even a date.

Then I got a call from the UK company. They wanted to talk to me about landing in the Crater. Whoa. I can’t do that. I’ve talked to the Meteor Crater folks and they won’t even let me land at their helipad, let alone inside their tourist attraction. I can’t get the amount of insurance they need (which is an unreasonable amount, but we won’t go there). Turns out that XYZ had told them I could land anywhere. Reality bites us in the ass.

They’re Too Anxious to Sell, Not Interested in Providing Service

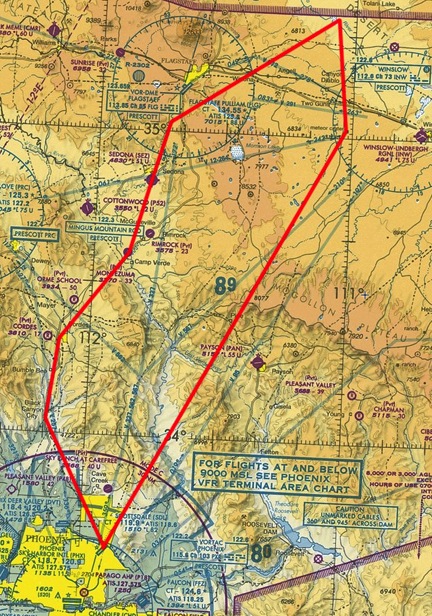

One flight I almost did for XYZ would have been above the cliffs in this photo.

Another time, a Phoenix-based company needed to do an aerial survey west of Page, AZ. I know that area very well; in fact, I’d been flying over the same spot less than a week before the call came and was excited about the possibility of flying up there again so soon.

The XYZ guy had a decent handle on the job and we were able to make arrangements with only three phone calls. Of course, one of the last phone calls concerned the date — XYZ had been so concerned about my ability to get the job done and the rate I’d charge that they neglected to tell me the date of the job. I was already booked for a flight that day. The client scrambled and offered a different date that worked for me. We booked the flight.

XYZ requires the client to pay, in full, at booking. The client did this, paying for a total of 5 or 6 hours of flight time. At XYZ’s rate for my services — 30% more than I charge. I didn’t see a penny of this money, but was assured that I’d be paid before the flight.

The client called me. They were having trouble getting landing permission from BLM, which they’d need for me to land. They were good people and did not expect me to land without permission. The flight would be delayed, possibly beyond their window of opportunity.

I didn’t hear anything more. A day before the flight I called the client to see what was going on. She was baffled. “Didn’t they call you? We had to cancel.”

They hadn’t called me.

“We couldn’t get our money back,” she added.

This bugged me. Someone had paid for my services and wasn’t getting what they paid for. I told her I’d try to get her a refund. I called XYZ and spoke to the guy we’d been dealing with. He told me, in no uncertain terms, that their payment and refund policy was none of my concern. I hadn’t provided any services, they weren’t going to pay me. (I would have turned the money over to the client.) If the client rescheduled — and they had a year to do so — they might call me back.

Competing with Myself

One of the things that annoys me about XYZ is its ability to be at the top of search results for any Google search where my company might appear. They do this with AdWords — paying Google to put them at the top of search results. It costs a fortune — I know because I used to use AdWords. I threw a bunch of money at Google for about six months and got absolutely no business from it.

XYZ, however, has 30% net on any booking and can throw that at Google or anyone else it needs to. So it comes to the top of the search results. People click that “sponsored ad” and two things happen:

- The folks at Google hear a little ca-ching!

- The person who clicked the ad sets himself up to deal with someone who knows little about the service he needs, pay a 30% premium on any tour he books, and lose the ability to get a refund if the project gets cancelled.

And when the price is too high for the market, I lose the business I might have gotten if they clicked the link to my site instead.

Parasites of the Tour Industry?

Parasite is a strong term and likely not as accurate as it could be. Companies like XYZ might believe they’ve got more of a symbiotic relationship with service providers like me. They might think that their advertising and ability to take calls in their call centers gets me more business.

But it doesn’t. It’s been four years since that first call and I have yet to get any work from them. Instead, they’re inaccurately representing my company and its rates to potential clients. I’m losing business because of them.

You might ask, then why not tell them to take a hike and stop calling?

Obviously, I can’t do that. After all, there is an off chance that they might actually get me some business. And in this market, it’s better to let a parasite suck some of your blood away than be blacklisted by a company that could throw you the few crumbs you need to stay alive.

Deal Direct, Not with the Middleman

The more important question is, why would people seeking tour or charter services be lured in to booking with a parasite company like XYZ?

I suspect there are multiple reasons, but the top one would be laziness convenience.

Consider the way you search for goods and services. You fire up your Web browser and enter a search for the service you need. A first page of search results appears. You see XYZ company right near the top. They’re also one of the “sponsored links.” You figure they must be big and have great service. You click the link. You make contact. Sure, they tell you, they can do that. Just give us a little more info so we can get you a quote.

Pretty easy for you, huh? One search, one click, one e-mail form or phone call. You don’t have to talk to more than one person. (Well, maybe you have to talk to him a few times while he gets all the information he needs.) You’re getting real service from a big company with locations across the country, right?

Wrong. You’re getting a telephone jockey who barely knows what you’re talking about. He’s picking up the phone and making some calls for you. He’s finding the deal that he thinks might meet your needs. He’s getting ready to lock you in on a no-cancel, no refund deal.

And he’s charging you a 30% premium for the work you could have done yourself, had you just looked past the first three search results.

You want to help small companies while helping yourself? Deal directly with the service provider and tell those parsites to take a hike. You’ll get the same — or better — service for a lot less money.