I bring electrical power into my building.

I don’t know if it’s a state or county law, but for new construction, a home owner has two options for setting up electrical power in their home: hire a licensed electrician to do all the work or do all the work herself. Because of my tight budget constraints, I elected to do all the electrical wiring myself.

Don’t get the idea that I’ve done electrical wiring work before. I haven’t. Any time something needed to be wired, I let my wasband do it. After all, he knew how and I didn’t. It wasn’t until he was out of the picture that I did my first wiring job: replacing a thermostat in my Arizona home. That was nothing compared to what I had ahead of me to wire a 2880 square foot garage and 1152 square foot living space. And a 6×8 foot shed 80+ feet away from the power source.

My Job

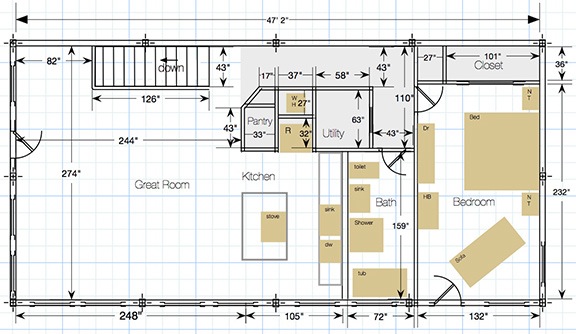

The Chelan PUD provides this illustration to show requirements for the conduit connection to the meter base.

The first challenge was installing the meter base and service panel. The meter base is the component that the power company — in this case, the Chelan County PUD — attaches the electric meter to. The wires come out of the ground, through a conduit I’d have to provide into a metal box on the outside of my building. The conduit had all kinds of size and component requirements and would have to be sealed to the meter base. On the other side of the wall I’d have to install a service panel with the circuit breakers that would connect to all of my electrical circuits. I had to not only mount both devices, but connect them with extremely heavy duty wires. In addition to all that, I also needed to run a copper wire from the service panel back outside the building and connect it to 2 8-foot copper rods driven all the way into the ground at least 6 feet apart.

(These requirements weren’t exactly new to me. After all, I’d installed my temporary power pole back in September 2013. But that was already partially cobbled together when I got it and I had an advisor to help me make the connections. The only part I knew how to do well was to drive in those grounding rods.)

In addition to all this, I’d also have to have at least one circuit installed in the panel. That circuit would have to run to an outlet and light, presumably with a light switch.

My work would be inspected by a government entity called Labor and Industries, which also sold me a permit before I started work. L&I, as it’s locally called, is responsible for all wiring inside a building; the PUD is responsible for wiring outside. L&I had to approve the installation of the meter base and service panel before PUD could connect power.

The Timing Issue

Coordinating visits by the PUD and L&I workers and inspectors was crucial and tricky. I had to know when each bit of work would be done so I could request services and inspections I needed.

Once the PUD turned off power to my temporary pole so we could finish the earth work in that area, I would not have power restored until I passed L&I’s inspection. I couldn’t pass that inspection until I installed the conduit, which had to be done as part of the earth work. PUD couldn’t reconnect my power until I passed the L&I inspection. Not only did all the work need to be done timely in a certain order, but the PUD and L&I work had to be scheduled properly.

That’s how I spent Thursday while I was on vacation out at Lopez Island. I excused myself from my host, sat down with a calendar and note paper, and made a bunch of phone calls. The result:

- Monday morning: Jeff the earth-moving guy and I would dig and install as much conduit as we could.

- Monday afternoon or Tuesday morning: L&I would inspect the meter base and service panel. I should have enough of the conduit installed to satisfy them.

- Tuesday morning: PUD would turn off temporary power.

- Tuesday afternoon: Jeff and I would dig and install the remaining conduit to the transformer box.

- Wednesday morning: PUD would connect permanent power to my building.

That was the plan, anyway.

The Meter Base and Service Panel

I bought everything I needed to mount the meter base and service panel. At least I thought I did. The funny thing about working on building projects is that no matter how many things you buy at Home Depot or Lowes, you always forget something. Or get a wrong thing. My primary destination these days is Home Depot, which is a 40-minute drive from my home. I’m there at least five times a week. (Maybe I should get a job there.)

On Sunday, my first full day home after vacation, I tried to start work. The trouble is, I couldn’t figure out how to mount the meter box on my building and I absolutely dreaded the thought of cutting a hole in the metal.

Bob drilled a hole in my building while I looked on, cringing. Since then, I’ve drilled more than a few holes in my building.

My friend Bob came to the rescue. He came by with tools and experience and advice. While his dog Skip and my dog Penny played together in the yard, he helped me decide on a location for the boxes — height was the primary issue that needed determination — and has the dubious honor of being the first person to drill a hole in my building. Of course, we didn’t have everything we needed to finish up, so we made the trip down to Home Depot together in my Jeep, stopping for tacos at the Plaza on the way back. (Have I ever mentioned the abundance of excellent, authentic Mexican food in this area? Whodathunkit, huh?)

Here’s the meter base right after mounting. I connected wires to the lower contacts, ran them through the hole, and connected them to contacts on the service panel on the other side of the wall.

By the time he left, the meter base was securely fastened outside the building with a “nipple” connecting it to the service panel securely fastened inside the building. I ran the three cables between the two panels and fastened them securely.

The First Circuit

Before leaving for vacation the week before, I had already wired my first circuit.

The outlet and light switch for my first circuit.

Although I’d wanted to set up the entry hall light with a 3-way switch to make accessible from both upstairs and downstairs, Bob had convinced me to keep it simple. So I wired up a 2-gang box with an outlet and single pole switch that ran to a fixture mounted nearby. The fixture was designed for the ceiling, but I mounted it on the wall, which meant the shade wouldn’t stay on it. I hoped the bare bulb wouldn’t bother the inspector.

Here’s my circuit board with my first circuit installed. I’ve decided to use 20 amp circuits throughout the building except for circuits that require higher amperage.

With the service panel in place, all I had to do was run the wires from the outlet into the service panel and attach them to the neutral bar and circuit. This was remarkably simple. It was also the only time I’d be able to work on the panel without worries about electrocution since there was no power running to it at all.

The Conduit and Grounding Rods

Here’s the 3-in conduit where it approaches my building. My job was to connect it to the meter base mounted on the wall above it.

I began running the required 3-in schedule 40 conduit the next day when we started the earth work.

Measuring and cutting the conduit to piece together required components to connect the sweep to the meter base was a bit of a challenge. My reciprocating saw made a mess of the plastic pipe when I cut it so I had to use my hacksaw. I got the measurements wrong once — fortunately, I hadn’t applied any glue yet — and had to recut a piece. But in the end, it came together well. I glued everything together, feeling relieved that the hardest part was done.

Although everyone had warned me that driving the two grounding rods into the ground would be difficult, I knew otherwise. I’d already done it once on my property — for the temporary power pole — and with a T-post driver the work had gone remarkably well. My building site is pretty much free of large rocks, as the builders discovered when they dug the holes for my building’s posts. Besides, with a 4-foot trench in the area, I only had to drive them 4 feet into the ground. As I expected, the work went quickly. I drilled a small hole through the building’s metal near the ground, ran an 8-gauge copper wire I’d bought as a remnant from Home Depot the day before from my panel to the two poles, and considered the job done.

I was now ready for inspection.

The First Inspection

The inspector showed up very late that evening. It might have been around 7 PM. He’d spent the day up in Chelan and I think the only reason he came that evening at all was because he lived nearby and had more jobs to do farther away the next day. Knocking off my inspection would leave him free to get to those other jobs first thing in the morning.

He checked the wiring of my outlet and light switch and seemed satisfied. Then he looked at the service panel. He disconnected the grounding wire, which I’d put in the wrong place. He was about to move it to the correct place when he realized it was 8-gauge wire. It was supposed to be 6-gauge.

Oops.

He said he couldn’t pass me until I replaced the grounding wire. He told me either he or another inspector would come back the next morning. I told him I’d have it taken care of.

Replacing the Grounding Wire

I absolutely dreaded the thought of driving all the way down to Home Depot that night or the next morning to buy more wire. As I was going to sleep, however, I remembered that I’d never cut the grounding wire on my temporary service pole. Instead, I’d left the extra wire coiled up beside the pole.

The next morning, I took my bolt cutters and cut the wire as close to the rod as I could. Then I went back to my building, disconnected the other wire, and ran the old wire through the hole. It was a stretch, but the wire was just long enough to go from the panel, down the wall, through the hole, and attach to the tops of both copper rods. Yes, I’d saved some money, but I’d also saved myself a trip to Home Depot.

The Second Inspection

A different inspector came to look at my work later that morning. He had a long beard like the guys in ZZ Top. He pointed out that the first outlet on a garage circuit needed to be a GFCI — a fact the previous inspector had neglected to mention. He also pointed out that I needed to clamp the conduit to the building in at least one place. But he passed me for PUD connection purposes, with the requirement that I make the two changes before final inspection.

I asked him whether I needed him to inspect the conduit that ran from the building to the shed where I planned to install power. He told me that L&I was responsible for inspecting anything on the inside of the circuit panel. Since the two circuits I planned ran from the panel back outside, he did need to inspect the conduit. Even though it wasn’t 100% complete — I still needed to bring the conduit into the building and shed on either end — he approved it. If he didn’t approve it, Jeff wouldn’t be able to bury it and that would hold up the entire project.

PUD Disconnects and then Connects

The PUD workers arrived a while later to turn off the temporary power. That enabled us to do the earth work needed to get the conduit right up to the transformer box.

From that point forward, I had no power at all. Fortunately, my RV has a solar panel on the roof that keeps its batteries — which I replaced just last year — fully charged. I could go without the microwave and coffee maker for a while. Later that day, I’d move the few items I had in the chest freezer into my RV’s freezer, which would operate on propane.

A while later that same day, a PUD engineer, who’d come primarily to consult with me about the possibility of moving the transformer, approved the conduit from the transformer to the meter base.

Jeff finished the earth work and buried the conduits, pipes, and telephone cable I’d run. (My property had a telephone line running to it and a huge roll of cable sitting beside it on the ground. Even though I don’t want a land line, the next owner might so I ran the cable in the trench. Not sure if I’ll bother to run it inside the walls, though.)

On Wednesday morning, the PUD guys came back. A crew of six ran the cable from the meter base to the transformer and installed the meter. When they were done, I had power in the building.

Success!

It worked!

I was alone when I flipped the main breaker in the service panel. Then I turned on my only circuit breaker. I reached over and flicked the switch for the light. The bulb lit up.

It may seem silly, but I consider the lighting of that bulb another major breakthrough in the construction of my new home. Like the day I held the keys in my hand for the first time, it’s a milestone — something that registered inside me as a sign that I was moving forward.

But what’s more important is that having electricity inside the building meant that I could begin the task of wiring the building. That means planning and adding outlets and lights and switches throughout the garage and living space above. It’s a huge task made more difficult by having to do it alone — try running wire long distances when there’s no one to feed it while you pull. But like everything else I’ve been dealing with for the past two years and much of my adult life, it’s just another challenge.

And I’ve come to realize that I live for challenges.