Real life turned to fiction from my files.

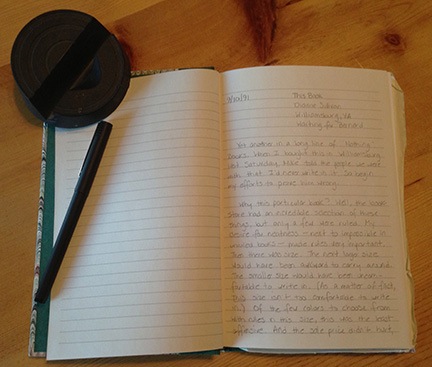

The following is a “short story” I wrote back in 1989. My sister might remember it; I’m pretty sure she read it back then. It’s a fictionalized account of a typical visit to my grandmother’s house in New Jersey. Out of all the things I wrote back then, this was one of my favorites. I found it earlier this month while cleaning out and packing up the papers in a closet.

My grandmother died about 11 years ago at the age of 89. Even on her death bed in the hospital she was looking ahead — “I’m going to be 90,” she said proudly to one of her visitors when asked how old she was. She was a hard-working woman who had a tough life. One of nine children, she began working in a garment factory in the Bronx when she was 15, lived through the Depression, bore two children eight years apart, had an alcoholic husband who later was paralyzed by a stroke, and worked until she was in her 70s. She was a simple woman with a minimal education who could do all kinds of mathematical calculations in her head.

I have her to thank for my work ethic, which has always convinced me that people who work hard (and smart) are rewarded for their efforts.

This is her birthday. She would have been 101 years old today.

I’m typing the 2,700 words of this story into my blog to help archive it in a safe place and share it with blog readers. I hope you enjoy it.

– = o = –

A Visit with Grandma

by M. L. Langer

The house sits on the right side of the street, beside the others it has been sitting with for the past forty-five years. It is a small, squat ranch, with a concrete terrace out front. There are five others on the street that looked exactly like it when they were new, but years of landscaping and home improvements make them look more like cousins now than the siblings they once were. This house has a dark green awning over the terrace — the stoop, your grandfather used to call it — and bright white aluminum siding. The driveway is straight and short; a rectangular piece of concrete with an irregular texture left on it from the sweeping broom that smoothed it down before it was left to harden. The grass is rich green and perfectly trimmed and, although it is the height of autumn and there are a number of trees in the yard, very few leave litter the lawn. Instead, they are piled neatly at the curb, waiting for the noisy vacuum truck to come by during the week and take them away.

You park on the street and start down the driveway, walking past the three-year-old Buick parked on the pavement. You remember the car before this one: another Buick, a pale green Skylark that had been bought the same year your brother was born. You remember seeing your grandmother maneuver it to the curb in front of your house when she was taking driving lessons and you remember hitting your head on the metal frame around the back window when, years later, it was rear-ended on the highway while she was driving you and your sister to visit your grandfather in his nursing home. For years your grandmother had said she was going to replace it, but it wasn’t until your brother was in his last year of high school that you finally dragged her to the Buick dealer and made sure she left a deposit on a new one. She still talked about the old one, and how faithful it had been all those years.

The garage door is open and you go inside, right up to the door in the back. You knock loudly, then open it, then shout into the house so as not to startle the woman you know is inside. The television on the kitchen counter is on, showing a commercial for a series of home improvement books; the announcer’s voice is blaring into the empty room. As you turn down the volume, your shout is answered by a voice coming from back toward the bedrooms. You wait, pulling off your gloves and jacket, and your grandmother appears, talking a mile a minute about how she was just getting ready to do some work in the yard.

You kiss her hello and ask why her house is so cold. Don’t you have the heat on? you want to know.

It’s on low, she tells you. Are you cold? I can turn it up.

But then she goes to the television and turns up the volume a little and starts telling you about how much trouble she had getting her neighbor to start her lawn mower for her the day before. In the middle of a sentence, she stops suddenly and asks you if you want tea. You say that would be nice and she goes over to the stove where a kettle is waiting. She fills it at the sink, now talking about a birthday party she is going to later on for one of the girls at work. You watch her put the pot on the stove, then turn on the gas beneath it. The automatic lighter clicks twice before the gas comes to life. She stops talking long enough to concentrate on lowering the flame, then starts up again, now about your mother and how she called just the night before. You sit down at the kitchen table and listen with one ear; you know that if you miss something important, you’ll get a chance to catch it later on.

While she talks and busies herself with a ceramic tea pot, you look at her carefully. She is a very short, stout woman, with an almost barrel shape to her. She is wearing one of her sweatsuits, this one black. The pants are too long and bag up around her ankles, the top is comfortably loose around her big chest and stomach. She has short blonde hair with silver gray roots. Her nose is long and hooked at the end; if it were green and had a wart, it would look just like the one on a witch. When you look at the face around it, the cliché wrinkled with age comes to mind. You remember all the times she told you she was going to get a face lift and how, each time, she’d pull the skin up and away from her face with her fingertips. It had always amazed you just how much younger she would look. But although she could well afford the expense, you knew she’d never do it.

From the sink, she asks you if you heard from your father lately. You tell her you haven’t. She tells you that she drove past his house a week ago and saw that he’d cut down another tree. Then she starts talking about one of the trees in her yard and about how many leaves come off it each fall. She tells you that she’s thinking of cutting it cut down. She asks you if you know who she can call about it and you tell her you don’t. You tell her to keep the tree, that it shades a quarter of the yard in the summertime. You tell her that if she needs help in the yard, you can come by with the blower. She tells you that one of her neighbors has a blower, then comes to the table with two cups and spoons and starts talking about the new menus they got at work and how much the price of a hot dog has gone up to. She tells you she doesn’t understand why people eat there because it’s so expensive.

You watch her go over to the cabinet under the television set and open it, talking the whole time. She bends over to get out some napkins, then asks if you want some cookies. You tell her you don’t, that you’re really not hungry, and watch her come back to the table with a package of Peek Freans anyway, now talking about how she went to pick up a few things at the supermarket earlier that morning. She tells you that she bought two bags of Halloween candy for the kids in the neighborhood and would you like to take some home with you? Before you can tell her you wouldn’t, she starts telling you about the time when your mother came to the elementary school to watch you and your sister in the Halloween parade and a man from the newspaper took a picture of her and your baby brother, who was wearing a Mighty Mouse costume. On Wednesday, when the paper came out, the picture was right on the front page. You remember the event well; you were about ten years old when it happened. You remember how your mother had drawn whiskers on his face with her eyebrow pencil. You remember the little mouse ears she’d sewn onto a sweatshirt hood. You just don’t remember what your costume had been that year.

Restless, you get up and walk over to the stove to turn up the flame under the tea kettle. Your grandmother is bending over the cabinet again, looking for something else while she tells you about the birthday party she’s going to later that night. It’s a surprise party, she tells you, and the birthday girl’s roommate is throwing it. She’s going to be twenty-two. She straightens from the cabinet with a package of the same brand of raisin cookies you’d been eating at her house for years and tells you about how the girl graduated from college in May but couldn’t find a job as a teacher so she still works at the store. She tells you that she doesn’t understand why girls go to school to be teachers when there isn’t enough jobs for them and the pay is bad anyway. She tells you that she tells all her friends at work about you and about how you’re a CPA. She pronounces the three letters clearly and separately, giving each equal importance. You try again to tell her that you’re not a CPA, that you’re just an accountant, but she’s not listening. She’s telling you how she told her friend Sally Connelly about your promotion and about the time she came to see your office.

She puts the package of cookies on a plate and sets it on the table while you walk over to the television and turn down the volume. Then you tell her you’ll be right back and you head down the hall to the bathroom, past the confused collection of valuable antiques and worthless nicknacks that sit side by side on tabletops and in glass-fronted cabinets all over the dining room and living room. On the way, you check the thermostat and find it set to fifty-five degrees. You turn it up to seventy, catching bits and pieces of her voice as she talks to you about your sister and her new apartment. Then silence as you close the bathroom door behind you.

When you come out, the tea kettle is whistling loudly and your grandmother is talking away, now about how she wants to have her bedroom repainted. As you come into the kitchen, she turns off the flame and removes the screaming kettle from the stove. She pours the water into the carefully prepared tea pot, telling you about how her mother used to dry out the tea bags so she could use them again. You open the refrigerator and retrieve a half gallon container of skim milk. You see the other things in there: cans of Shop Rite soda and eggs and blackened bananas. You ask her why she has beer in the refrigerator. She tells you she keeps it for when Sally Connelly and her boyfriend come over. Her boyfriend John likes beer. Then she starts telling you about what your mother had to say on the phone when she called the night before.

You sit down at the table, putting the milk down on the plastic tablecloth beside a tin tray of Sara Lee pound cake that she must have pulled out of the freezer and sliced while you were in the bathroom. She comes over with the tea pot, which is now wearing a crocheted sweater your mother calls a tea cozy. You look at her hands as she pours your tea, telling you the whole time about the trouble your mother and stepfather are having with the roof and how much money the men want to fix it. Her hands are small but broad, with short, crooked, big-knuckled fingers. Hands that have done a lifetime of work. Real work, not the writing and punching of calculator keys that your hands do. These hands helped raise sisters and brothers. They went to work in the sweater factory at age fifteen and didn’t retire from that work until they were age sixty two. They raised two children and kept a spotless house for a husband. They tended to that husband when he got ill, bathing and feeding him until the task of lifting him out of bed every morning became too much for them to handle and was turned over to more experienced, less loving hands. Now, five days a week, they go to work in the restaurant where they scrub tables and seat customers. They take care of the house and the lawn, they scoop leaves out of the gutters and pull down the heavy, dark green awning every year. They make tea for you when you visit and, when you leave, they take the dishes out of the dishwasher and wash them by hand.

She puts the pot down on the table, now telling you that she gave your brother fifty dollars before he went back to school because he needed a new pair of sneakers. She walks over to the sink to rinse off a knife that she used to cut the pound cake, talking about how big your brother is getting. You tell her to come sit down, that her tea is getting cold. Then you get up and look in the cabinet on the right of the stove for the sugar bowl. She opens the cabinet on the left and removes a jar filled with sugar packets from the restaurant, then comes back to the table with you.

You sit there drinking your tea, eating Peek Freans and partially frozen Sara Lee pound cake. She sits on the edge of the chair across from yours, a piece of pound cake in her gnarled fingers, telling you about your cousin in the Marines and how beautiful his two sons are. She tells you that she spoke to the older son last week while she was at your aunt’s house and that he told her he missed her and wanted her to come to North Carolina to visit him. You listen with one ear again, thinking about the chores you’ve got to do at home and wondering what you’re going to make for dinner.

When your second cup of tea is gone and she starts telling you about your mother’s phone call for the third time, you realize that it’s time to go. You rise and start clearing plates and cups from the table, putting them in the dishwasher. She tells you not to worry about it, that she’ll take care of it, that it’s no bother. Then she helps you, telling you about her boss and how much he thinks of her because she helps clear the tables when other hostesses don’t. She tells you that he gave her a raise and you wonder if it’s another raise or the same raise she told you about last time you visited. Then she starts telling you about your uncle and how he came by the store one day last week while she was working. You listen politely, pulling on your jacket and gloves. Then you thank her for the tea and bend down to give her a kiss on the cheek. The kiss comes with a hug and you hug her back, feeling how small and warm and soft she is and remembering, for a minute, all the times you slept over her house when you were younger and how she made farina and tea with lots of milk in it for you in the morning. You remember your grandfather, now long gone, and how he used to call you skinny melinks. You remember how you and your sister used to get into the old, green Buick with them on autumn days like today and go to the farm stand where you’d get apples and pumpkins.

Then the hug is over and you stand up straight again, telling her that you’ll invite her over for dinner soon. You go out the door and she follows you, talking about what nights she works and what nights it’s best for her to come. It’s cold out and she’s wearing only her sweatsuit and slippers. You can see wisps of vapor by her mouth when she talks. You tell her to go back inside, that it’s too cold to be out without a coat on, but she follows you down the driveway anyway, right to the end where your car is parked. As you get into the car, she bends down to collect a few leaves that lay on the grass near the curb, then points up to the tree in the side year, saying something that you can’t hear through the closed windows of the car. You start the engine and toot the horn once, then wave and drive away.

THE END

We gave the trails names. The Golf Course Trail was the one that went from the gate to Rancho de los Caballeros’ golf course. Deer Valley Trail was the one that rode through a valley where we almost always saw deer on a morning ride. Danny’s Trail was the one our neighbor, Danny, showed us on the only time he went riding with us. The Ridge Ride was the one that stretched along a high ridge overlooking the golf course and points north on one side and the big, empty desert and points south on the other side. Yucca Valley was the strip of sandy wash filled with an unusually large number of yucca plants.

We gave the trails names. The Golf Course Trail was the one that went from the gate to Rancho de los Caballeros’ golf course. Deer Valley Trail was the one that rode through a valley where we almost always saw deer on a morning ride. Danny’s Trail was the one our neighbor, Danny, showed us on the only time he went riding with us. The Ridge Ride was the one that stretched along a high ridge overlooking the golf course and points north on one side and the big, empty desert and points south on the other side. Yucca Valley was the strip of sandy wash filled with an unusually large number of yucca plants. As we reached the highest point on the Ridge Ride trail and stopped to look out over the desert, I remembered toasting the new year with my husband and friends on New Year’s Day rides. I began to regret volunteering to take my new friends on these trails. Would I be able to keep it together that day? Would the pain I felt so intensely be noticed by my companions?

As we reached the highest point on the Ridge Ride trail and stopped to look out over the desert, I remembered toasting the new year with my husband and friends on New Year’s Day rides. I began to regret volunteering to take my new friends on these trails. Would I be able to keep it together that day? Would the pain I felt so intensely be noticed by my companions? I led the group out onto the trail, feeling a weird mix of emotions. But as we hiked and as I talked about the things we were seeing, the ghosts from the past stayed away. Although I thought about those long ago horseback rides, I was more focused on sharing the trails — my trails — with my friends, pointing out plants and rocks and other items of interest. I realized, as we made the final ascent to the highest point on the Ridge Ride trail, that bringing my friends along helped me make new memories of the trails, fresh memories that helped the old ones — and the pain they conjured — fade away.

I led the group out onto the trail, feeling a weird mix of emotions. But as we hiked and as I talked about the things we were seeing, the ghosts from the past stayed away. Although I thought about those long ago horseback rides, I was more focused on sharing the trails — my trails — with my friends, pointing out plants and rocks and other items of interest. I realized, as we made the final ascent to the highest point on the Ridge Ride trail, that bringing my friends along helped me make new memories of the trails, fresh memories that helped the old ones — and the pain they conjured — fade away. The only time I got teary-eyed is when I stopped at that “three-finger cactus” and asked one of my friends to take a picture of me with my dog. Even then, I don’t think anyone noticed the tears behind my sunglasses.

The only time I got teary-eyed is when I stopped at that “three-finger cactus” and asked one of my friends to take a picture of me with my dog. Even then, I don’t think anyone noticed the tears behind my sunglasses.