The other half of the weight equation.

Last week, I wrote a blog post about helicopter weight. It was my response to a blog post by Tim McAdams on the AOPA helicopter blog titled “Gross weight.” The comments to that post indicated to me that some of the commenters were confusing weight with CG — center of gravity — issues. My blog post concentrated on weight, putting CG aside. But CG is the other part of the weight equation. And for most helicopters, CG is vitally important to calculate as part of preflight planning.

CG Defined

Center of gravity is pretty much what the phase indicates: a calculation of the center of gravity on an aircraft. It’s the aircraft’s balance and it’s calculated as part of the “weights and balance” computations.

For helicopters, CG is extremely easy to envision. After all, a helicopter with a single main rotor system (as most have) is supported at one point in flight: the main rotor system or mast. If you held up the helicopter by its rotor system, the distribution of its weight — not just what’s inside it but its engine, battery, tail rotor, etc. — would determine how level it hung.

Take, for example, my R44. Its full passenger load is in front of the mast. Its fuel, engine, and heavy components are slightly aft of the mast. For this reason, if I’m flying solo (just one person up front) with low fuel, the helicopter would be a bit tail heavy. As I set down from a hover to the ground, the back of the skids would touch the ground before the front. In fact, the right back would touch first. That’s the lowest point closest to the center of gravity for that load.

The same applies to R22 helicopters. In fact, it’s often terrifying for student pilots to pick up into a hover after their flight instructor steps out when its time for that first solo flight. (Sure scared the hell out of me.) The helicopter feels as if it’s going to flip over backwards!

But stick a pair of fatties up front in my R44 and the CG will shift forward. In fact, if you have enough of a load up front, the fronts of the skids will touch first on landing. (I remember the first time I flew with my brother-in-law on board. I thought I was landing on a slope!)

Watch any helicopter take off or touch down and you’ll probably be able to tell where its center of gravity is.

Why CG Is Important

CG limitations are important for aircraft operation. For example, if you’re loaded with too much weight up front, the helicopter will tilt forward more in flight. When slowing down, stopping, or hovering, you might not have enough aft cyclic to counteract this forward tilt. Ditto for lateral or aft CG.

Remember, every aircraft control has a “stop.” That’s the limit to the control’s movement. You pull the cyclic back to slow down in flight. If you’re heavy up front, you may have to pull it back to simply hover in place. If you’re so front heavy that you can’t pull the cyclic back enough to stop the helicopter from moving forward, you have a serious problem — a problem with your CG or balance.

Want to see how far your controls will move? You should be checking their movement before starting up by simply moving each of the controls as far as it will go. The idea is to make sure none of them are stuck on anything or binding in any way. You don’t want to learn about a control problem when the engine is running, rotors are spinning, and you’re picking up into a hover.

You Can Be Under Max Gross Weight and Still Out of CG

What was bothering me about the comments on that AOPA blog post was that a few of the early commenters kept referring to CG and “weight and balance.” But the blog post was about gross weight. CG wasn’t discussed at all.

I didn’t address CG in my post because that wasn’t being discussed. In fact, it’s quite possible to load an aircraft out of CG and still be within max gross weight.

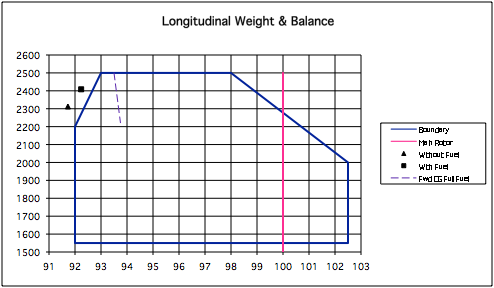

This aircraft is out of CG but still within gross weight limitations.

Want an example? Here are the plotted points for a W&B calculation for an R44 helicopter with 4 good-sized people on board (190 and 250 up front; 190 and 145 in back). It’s a short flight, so only 16 gallons or about an hour’s worth of fuel is loaded on board. The total weight of the aircraft is 2408 — that’s nearly 100 pounds below max gross weight. But as the graph points show, this aircraft is out of CG — too much weight up front.

If you’re having trouble reading this, envision the pink line as the mast. Everything to the left is the front of the helicopter. Everything to the right is the back end of the helicopter. The blue box is the CG envelope for the aircraft, as determined by the manufacturer. In this example, the aircraft with and without fuel is loaded forward of the CG envelope. That’s a no-no.

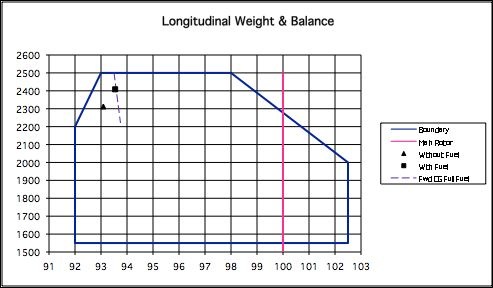

The same passengers as in the previous example, but with heaviest and lightest passengers switched. This load is within CG.

This situation is extremely easy to fix. Simply rearrange the passengers. While you can’t move the 190-lb pilot, you can move the fatty beside him. In this example, the 145-lb passenger in back has switched places with the 250-lb passenger up front.

Adding fuel might help, since fuel is loaded aft of the mast. But you couldn’t add much — you’re already pretty darn close to max gross weight.

Of course, both of these examples show only longitudinal CG — forward to aft. Lateral, or side to side, CG also needs to be calculated. As many of the commenters pointed out, they’ve created spreadsheets to perform these calculations for them. So have I — where do you think these two diagrams came from?

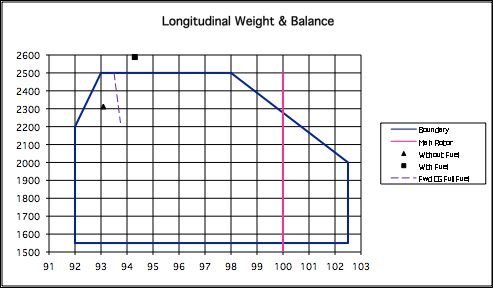

Take the balanced load of the second example and top off the fuel tanks and you’ll get a situation like this.

Can you be over max gross weight and within CG? Technically, no. As these two diagrams indicate, if you’re loaded too heavy, the plot points will be outside the CG envelope. That means you’re out of CG.

But are you really out of balance to the point where you’ll run into control issues? I wouldn’t want to find out for myself.

Which is More Important: Weight or Balance?

I’ll always argue that you need to consider weight before you worry about balance. If you’re too heavy to fly within manufacturers max gross weight allowances, you’re too heavy to fly legally. Who cares about balance at that point?

So if you’re too heavy, it’s time to reduce weight. Leave behind some gear. Take less fuel. Leave behind the passenger who really doesn’t need to come along. Can the mission be flown with the load changes? If so, go the next step with the new load and do the complete CG calculations. Are you in CG? If so, you’re almost ready to go.

Almost? What else is there?

Performance, of course. I’ll discuss that in a future post.

Anyway, outside the theater were movie posters for coming attractions, including this one for an upcoming Jackie Chan movie called The Spy Next Door. And it doesn’t take a helicopter expert to recognize all three helicopters in the poster are R44s.

Anyway, outside the theater were movie posters for coming attractions, including this one for an upcoming Jackie Chan movie called The Spy Next Door. And it doesn’t take a helicopter expert to recognize all three helicopters in the poster are R44s.

Today, I made sugar cookies in the shape of helicopters for my

Today, I made sugar cookies in the shape of helicopters for my  Roll batter out to 1/4 inch thickness on floured board.

Roll batter out to 1/4 inch thickness on floured board.