Why yes, a helicopter can camp with the airplanes at an AOPA event.

With cherry season over, travel season has begun for me. I started with a week-long road trip with my truck and the Turtleback at the beginning of the month. At mid-month, I set off in my helicopter for a four-night adventure with my favorite co-pilot, Penny the Tiny Dog.

About the Fly In

I’ve been an AOPA (Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association) member for almost 20 years now — from the very start of my aviation training. Back then, I joined up primarily to get an AOPA credit card, which would give me a 5% rebate on all of my flight training. When you’re spending $200/hour for dual time in a helicopter — the going rate back in the late 1990s — 5% back is welcome. Later, AOPA helped me finance both of my helicopters, including the R44 I bought back in 2005 and still own.

I get AOPA’s magazine, Pilot, and write for their helicopter blog, Hover Power, which has apparently been merged with their regular blog. I’d heard a lot about their fly ins, but none of them were ever convenient to attend. But this year was different. This year, there was a fly in in Bremerton, WA, which was about an hour’s flight time due west of my home in North Central Washington. Best of all, it was after cherry season, so I’d be free to attend.

A “fly in,” if you’re not familiar with the term, is a gathering of pilots who fly in to a destination. There’s usually something there to draw them in. Often, it’s something as simple as a pancake breakfast or barbecue. But when the fly in is sponsored by a larger organization, such as AOPA, there’s usually a lot more. In Bremerton, there would be seminars, vendor booths, parties, display aircraft, and that all-important traditional pancake breakfast.

The timing was right — I had nothing else on my calendar (although I admit I turned down two charter flights for that weekend). Best of all, the weather would be perfect for a direct flight over the Cascade Mountains. And I even had one or two destinations for after the fly in so I could extend my weekend from two nights to four.

A Stands for Aircraft

As I sort of expected, it wasn’t going to be as easy to arrange as I’d hoped.

The camping information I was promised when I signed up never arrived in my email in box. (Oddly, a lot of stuff I’ve been expecting has never arrived; I’m beginning to think I’ve got email issues.) When the Bremerton Fly In website proclaimed that camping was full, I decided to follow up with AOPA. I was bounced from one person to another and finally began an email exchange with a woman named Paula who could help. She confirmed that I was registered for camping. But because I was flying a helicopter, they’d park me on the “north ramp” and help me get my gear over to the camping area.

So I would not be able to camp with my helicopter?

No, Paula told me. They can’t have helicopters with the airplanes. There were only two helicopters signed up and the other one wasn’t camping.

I told her that was unacceptable. I told her I wanted to camp with everyone else and that I needed my aircraft as a place to secure my valuables. I reminded her that the A in AOPA stood for Aircraft and not Airplane. I told her I’d been a dues-paying member for almost 20 years and was entitled to the same treatment as all other members.

She was at a loss for how to proceed, so I helped out. I told her I’d be arriving early on Friday and departing Sunday. Surely they could park me on the edge of the camping area and let later arrivals fill in the space between me and the folks that arrived before me.

To my surprise, she agreed. She said that many people arrived late on Friday and most left on Saturday so that should work.

I told her I’d be there sometime between 2 and 3 PM on Friday. I also told her I’d bring wheels in case I needed to be moved on the ground.

And then I set about packing.

Packing for the Trip

I do two kinds of camping: tent camping and RV camping.

RV camping is easy; almost everything I need is already stowed in the Turtleback. I add food and clothes, put it on the back of my truck, and set off.

Tent camping takes a bit more effort to prepare for. I stow all of my tent camping gear in two wheeled tool boxes. If I’m going on a regular car camping trip, I add food and clothes to those boxes, include a cooler with ice block jugs for cold items, and gather together items from the Turtleback, like my portable grill and fuel. When I went camping last summer with the guy I was dating at the time, we crammed all this stuff into the back of my Jeep. The wheeled boxes make it easy to transport camping gear from a vehicle to a campsite that might not be nearby.

I don’t go backpacking anymore. At least I haven’t for a very long time. I have no desire to do so and it would be a hard sell to get me to change my mind.

Camping with the helicopter would be a little more challenging. I had room for the smaller of the two wheeled boxes, but not both. Fortunately, I didn’t need all the gear in both boxes. I’d need a small cooler, but not my grill. I’d need a stove and percolator, but not a mess kit. I’d need a tent, but not a large tarp. So I had to go through all my gear and get what I needed packed into the smaller of the two boxes. Tent, air mattress, sheets, fleece sleeping bag, chair, throw rug, lamp, small tarp, stove, fuel, percolator. Most of it fit right into the bin. The rest, including a small cooler with milk for my coffee, dog food, drinks, and other food items, filled the back seat area of the helicopter. I added my orange traffic cones and ground handling wheels. My weekend bag full of clothes went under one of the back seats.

I put Penny on her bed on the front passenger seat — there was no room for her in back — and at around 12:30 PM on Friday, we set off for our long weekend.

The Flight West

We stopped at Pangborn Airport to get fuel before heading west. I had to wait behind two other airplanes fueling up. Is it my imagination or are there more planes flying at Pangborn these days?

I set my panel mount GPS for Auburn Airport and Foreflight on my iPad (EFB) for Don Johnson’s Home heliport. Don (not the famous one) is a friend of mine who owned a helicopter until just a few years ago. He recently accompanied me on a flight from the Sacramento area to his home in Auburn, WA. Don had a pair of helicopter door covers he no longer needed and wanted to give them to me. Since his home was on the way and I hadn’t seen him for a while, I figured I’d drop in for a few minutes.

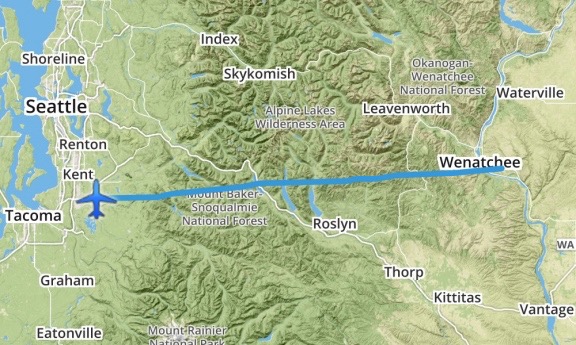

The sky was cloudless and winds were light when we took off from Pangborn heading almost due west. My track would take me straight over the Cascade Mountains, between Stevens and Stampede Passes. This is a sort of “no mans land” for pilots — once I left the Wenatchee area, I’d pass over just two paved roads for the next 50 or so miles of the 80 nautical mile distance. In between were steep, rocky mountains peaks, steep slopes, mountain streams, and lakes. An engine failure would be a very bad thing — but any pilot who flies chooses a route based on the convenience of an engine failure along that route probably shouldn’t be a pilot.

My route west took me straight across the mountains. This is my actual track, recorded by ForeFlight.

I climbed out gradually, crossing each ridge I reached at a few hundred feet above it. Crossing the Cascades isn’t a big deal on a clear day. Although I honestly can’t remember the highest altitude I reached, I doubt it was more than 6,000 MSL. While a lot of sea level pilots might think that’s high, I learned to fly in Arizona, where there are many airports at 5,000 feet elevation or higher and mountain ranges that forced me above 8,000 feet to cross. The air smooth for most of the flight, although it did get a little rough when I reached the lakes far below me between Cle Elum and Snoqualmie Pass. I crossed I-90, continuing west. Mount Rainier towered in the near distance, snow-covered and serene. I remembered the flight I’d done a year or two before, following the course of the Green River to the base of the mountain and thought again about the deserted fire lookout tower we’d found perched on one of the mountain’s north-reaching arms.

From there, the terrain was mostly downhill. I descended, letting my speed creep up to 120 knots at times. The lower we got, the warmer it got. I opened the front door vents and the main cockpit vent. Penny stirred in her seat yet again — her bed was in the sun and I could tell that she was frustrated that she couldn’t climb in back. It was hot enough without a black fur coat on.

We got close to Don’s house and, as usual, I had to hunt around a bit to find it. The GPS coordinates on Foreflight were off by at least 1500 feet. I knew some of the landmarks and, of course, I knew what Don’s house looked like from the air. But the area was thick with tall trees. I finally caught sight of it, then set up for a straight in approach on my usual route in. It’s a steep descent; you can see a video of it in my post about my April flight with Don. As I came in, I saw two of Don’s garage doors closing; he was working in one of his garages — he has 10 — and was trying to prevent my downwash from blowing things around in there. Then we were on the ground and I was cooling down and Don was outside waiting for me. I let Penny out to run around with Don’s dog while I shut down the engine.

We chatted for a while and he gave me the two door bags, which I managed to squeeze into the helicopter with the rest of the gear in the back seat. Then we went inside for a cold drink. When he heard I was camping, he insisted on giving me a battery operated fan he’d used on a recent overnight bike ride. He said it had been so hot every night that he would have been lost without it. He gave me a fresh set of batteries to go with it, too.

I was already running late for my promised early arrival at Bremerton, so I didn’t stick around long. I got Penny back in the helicopter, said goodbye to Don, and started up. It was just after 2 PM when I climbed out the way I’d come.

Arrival at Bremerton

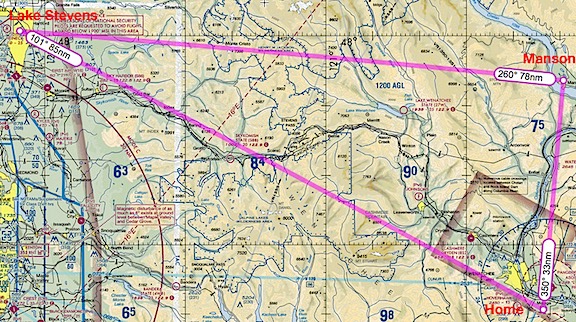

AOPA released an 18-page PDF with arrival procedures for the fly in. It contained detailed instructions on how airplanes coming in from just about any direction should approach and enter the traffic pattern. Although Bremerton is not a towered airport, there would be an Air Boss directing traffic. The document listed frequencies, provided waypoints (with GPS coordinates), and showed maps. If you were flying an airplane and had any questions about flying in, this document would answer it.

Unfortunately, the word “helicopter” did not appear anywhere in the document. There were no helicopter instructions at all.

Airplane pilots might be thinking, so what? Just follow the airplane instructions. But that’s not what helicopter pilots are supposed to do. FAR Part 91.126(b)(2) is clear on this:

Each pilot of a helicopter or a powered parachute must avoid the flow of fixed-wing aircraft.

To me, that means don’t follow the instructions in that 18-page document.

So what do I do? Fortunately, I knew exactly what the airplanes would be doing so they would be easy to avoid. I also knew that the Air Boss would be directing traffic. I figured I’d fly in as I normally would: direct to the airport and make a call a few miles out with my intentions. In this case, however, I’d be calling the Air Boss with a request and take his orders for landing.

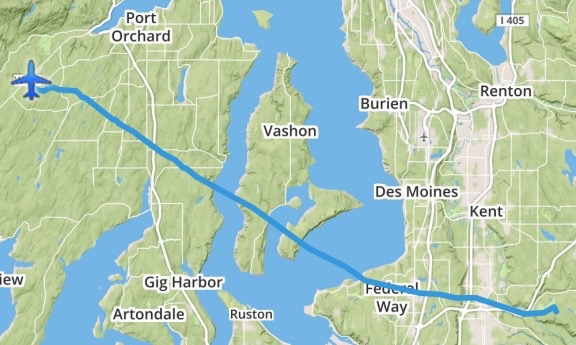

I skirted around the south side of the surface airspace for Seattle Tacoma Airport (KSEA or SeaTac) and headed directly for Bremerton. I admit that I wasn’t too happy flying over the south end of Puget Sound — all that open water! I climbed to about 2000 feet to make a glide to land in the event of an engine failure just a little more possible. Then, on the other side, I descended to about 1000 feet, taking in the scenery around me. It was hazy from fires that were burning on the Olympic Peninsula to the northwest. I was flying over a land of forest-covered islands with straits between them.

Here’s my route from Don’s place to Bremerton.

I tuned into the frequency for the Air Boss at Bremerton. It was busy with pilots calling in and the Air Boss patiently telling them to follow the procedures for approach. Occasionally, he would clear airplanes to land and provide taxi instructions. Once, he urged a pilot to get off the runway because another plane was landing behind him. (That 18-page document said, in several places, that pilots should not linger on the runway.)

I didn’t have the airport in sight when I called in from 3 miles out. I was only 500 feet up, avoiding the flow of fixed-wing traffic by staying below the traffic pattern altitude. “Bremerton Air Boss, helicopter six-three-zero-mike-lima is three east landing for camping.”

There was a pause before the Air Boss replied, “Are you the one that called in?”

“I’ve been emailing with Paula,” I told him. (I should mention here that a benefit of being a member of the female pilot minority is that my voice is easily distinguishable from other pilots on the frequency, making it possible to skip identifiers once in a while. Normally, I’d include my N-number in every radio communication.)

“Okay, zero-mike-lima. We know where to put you. Do you see that airplane on downwind?”

I looked. At that point, I could see a plane flying south at what might be traffic pattern altitude. “Zero-mike-lima has that traffic in sight.”

“I’m going to want you to make a lower traffic pattern to the south, outside of his,” the Air Boss said.

As I tried to envision what he wanted, the runway came into view. There was no one on base or final. It would be so easy to just dart across the runway. But I obediently started a turn to the southwest. “Zero-mike-lima turning downwind.”

“I’ve got you in sight now,” the Air Boss said. “Zero-mike-lima, just cross the runway to taxiway alpha and turn south. They’ll direct you.”

“Zero-mike-lima crossing the runway.” I banked to the right and bee-lined it for the taxiway on the opposite side of the runway. I found myself in a hover not far from where some airplanes were parked with tents set up. South would have taken me farther away from them, completely out of the area. So I turned north, figuring he’d made a mistake, looking for someone to flag me in.

A guy with two orange sticks like the kind they use to direct airliners was at the north end of a grassy parking area, directing me in. I followed his instructions to set down at the top of a tiny slope where stakes had been put in to prevent pilots from driving down the little hill. There was some confusion when he had me park perpendicular to all the other aircraft and I asked him whether I could turn sideways. He said he knew helicopters needed to take off into the wind so he thought I’d like that direction better. But the wind was a tiny breeze and I wasn’t taking off for two days. So he let me park facing west, which turned out to be a good thing when the sun really beat down on my camp.

I put Penny on her leash and dropped her out the door while I cooled the helicopter’s engine and shut down. We had arrived.

Making Camp

As I had suggested, they parked me at the edge of the airplane camping area. In the hours to come, they’d start parking other airplanes west and south of me. After climbing out and chatting with Paula, who’d come in a golf cart to greet me, I set up camp.

The breeze was just enough to keep me on my toes as I set up my little domed tent, which I’ve had for at least 20 years. It’s a good quality tent with a rain fly that really works — I can tell you from experience. I had bought new stakes for it and brought along a small sledgehammer to drive them in. I only staked the four corners. Then I inflated my air mattress using a rechargeable air pump I’d bought a few weeks before and made the bed with clean sheets. I opened my fleece sleeping bag and draped it over the bed as neatly as I could. It was going to be hot that weekend — it had already topped out at over 90°F — and I couldn’t imagine needing more. I set Don’s fan up nearby and hung a small battery lamp from the top of the tent. I didn’t bother with the dark blue tent fly — I knew from experience that it would turn the tent into a small oven.

My campsite, right after setting up.

I stowed the gear I didn’t need back in the rolling box and set up my stove on the lid. I set up my chair beside it and my cooler beside that. I set the stack of cones — I really only needed one — under the end of the forward facing rotor blade to prevent a fuel truck or some other tall vehicle from driving where a blade strike might be possible.

I was just putting up my wind ribbon on a pole when Paula drove up again. “I can tell you’ve done this often,” she said.

I laughed. “No. This is only my second camping trip with the helicopter. But I’d like to do it more.” (The other time, in case you’re wondering, was at the Big Sandy Shoot way back in 2006.)

By this time, the sun was starting to dip to the west and the north side of the helicopter was in the shade. I settled down on my chair for a rest and to cool down. Penny, who’d been off her leash for a while, had to go back on it; other pilots were arriving and more than a few had dogs Penny wanted to visit with. I set her up with some cold water and food and watched the world go by while sipping an ice cold lemonade from my cooler.

Friday Night at the Fly In

It was probably around 5 PM when Penny and I headed toward the main event area. I didn’t have any tickets for any of the meal events and needed to buy them. I also needed a schedule of the seminars and other activities that would keep me busy on Saturday.

Some of the AOPA guys and vendors were still setting up, but the place was pretty much ready for the event. I wandered around, getting the lay of the land — the main event tent, the smaller session tents, a handful of vendor booths, and the big exhibition tent (which was closed). A bunch of airplanes were on display, including Miss Veedol from Wenatchee. I chatted briefly with Tim, one of the pilots who I already knew. Like me, he’d had a smooth direct flight across the Cascades.

I bought tickets for that evening’s party, the Saturday pancake breakfast, and Saturday’s lunch. Then, since it was hot and there wasn’t much else to do, I headed back to my camp.

A woman wearing a propeller beanie hat and riding a bicycle rode over to chat. Her name was Patrice and she was soon joined by her husband Pat who I’d apparently met (but, as usual, didn’t remember) in Wenatchee when he’d stopped in on a flight. Other people came and went. Some asked questions about the helicopter. I saw one person take a photo of my campsite when he thought I wasn’t looking.

After a while lounging around, studying the program, and catching up on social media, I headed back over to the event area. Although I’d arrived right on time for the party, there was already a long line for food. Penny and I queued up. I chatted with a couple on line behind me as we inched forward. Dinner was pulled pork with cole slaw and beans. And one of those Hawaiian rolls that was so good I finished it before I got to the salad bar.

Although I saw Patrice, who was looking for Pat, I wound up having dinner with Tim and the Miss Veedol gang. Tim had said to me that I had to meet his new friend Barry, who was also a writer. Barry, who was with them at dinner, turned out to be none other than legendary pilot/author Barry Schiff, a man who has been writing about aviation almost as long as I’ve been alive. We chatted a bit about writing and he got me motivated to get back to work on my flying memoir. (A winter project?)

All the time we were eating and chatting, a live U2 cover band was playing outside on a stage set up in front of the B-25, “Grumpy.” As night fell, it got cooler. There were stars and a big moon. It was great to be among so many pilots, most of whom were camped out for the night. I said goodnight to my companions and headed back to camp with Penny. I let her off her leash for the walk between airplane tent camp sites and she tore around like a crazy dog, excited to be let loose after hours of being under foot and under tables. I made a quick stop at the blue plastic building — which had a nice hand washing station beside it — along the way.

They set up the band in front of “Grumpy.”

First Night at Camp

Back at camp, I took a few moments to attach the rain fly to the tent. Despite the fact that it had gotten very warm during the day, it had cooled off considerably. My tent has thin nylon walls, which makes it great for summer camping. But in cold weather, it really needs that full-sized rain fly to provide a layer of insulation. The wind had died down completely, so it was an easy job. I staked it out away from the tent in the back so I’d get air flow through the back window, as well as along the staked poles, not really knowing what to expect.

We crawled into the tent and settled in for the night. I closed the screen but left the door panel open. I got a reasonable flow of air through the tent. That was great — when I first lay down. But as the night progressed, the air got cooler and cooler. I woke up in the middle of the night, thoroughly chilled. After a quick walk in the moonlight to the blue building, I closed up the tent more securely, hoping to keep more warmth in. But I slept fitfully for the rest of the night, feeling the cold ground come up through the bottom of my air mattress. My fault entirely — I’d expected it to be very warm and it wasn’t. I’d have to redo the bed for Saturday night.

Saturday at the Fly In

It was light out — although the sun hadn’t yet risen — when I fully woke the next morning. I threw on some clothes and stepped outside for another visit to the blue building, this time with Penny in tow. It was a perfectly clear day with the temperature probably in the 60s. The sun felt good when it rose above the trees to the east and shined down on my little campsite. Other campers were stirring.

First light at our campsite on Saturday morning. It was a beautiful day!

I “fixed” my coffee pot size problem with two heavy tent stakes. And no, the plastic parts did not melt.

I prepped the percolator to make a cup of coffee and got my first surprise: the pot was too small to fit on the metal brackets over the burner! ! Instead, it slipped down onto the actual burner, extinguishing it. I felt a moment of panic before annoyance took over. Surely I could do something to make this work. The solution turned out to be two of the tent pegs positioned on either side of the burner. The pot sat atop them. Problem solved. I was drinking fresh, hot coffee a short while later.

Other than a few snacks, I hadn’t brought any food — at least not for me. I did bring food for Penny, which I put out for her. She sniffed it and gave me a look as if to say, “You’re kidding, right?” For the rest of the trip, I’d be sharing my food with her.

After I made a second cup of coffee and dressed for the day — at which time I decided I needed a larger tent that I could actually stand up in — we headed over to the main event area. Breakfast lines were surprisingly short. I had pancakes and sausage, sitting inside the main tent with two pilots from Canada.

Then it was off to the seminars.

The first was about ADS-B, a new ATC tracking system that will be required on all aircraft that fly wherever a Mode C transponder is required — basically within 30 miles of any Class B airspace (think Seattle, Phoenix, Denver, LAX, JFK, etc.) — by 2020. I had a vague idea of what ADS-B was and what it might entail in the way of avionics upgrades, but by the end of the session I completely understood what I’d have to do and how I might benefit. I say “might” because I generally fly too low to be picked up on radar around where I live — literally “below the radar” — and since the ADS-B stations are ground based, I wasn’t likely to be picked up by any of them, either. But if I had a dual band receiver, I could pick up signals sent out by other ADS-B equipped aircraft so I’d see them on my GPS screen — if my systems were compatible.

After that session, the next time slot didn’t have anything that interested me — remember, this event was primarily for airplanes and so much of what the sessions covered simply didn’t apply to helicopter flying — so I decided to take that time to visit the vendor tent. I was mostly interested in applying what I’d just learned to figure out what my upgrade options were and what they’d cost me. There wasn’t much memorable about the vendor area except a few ForeFlight clones, a very crowded Garmin and ForeFlight booth, and a handful of vendors specializing in products or services for airplanes.

ForeFlight, in case you don’t know, was the first successful iPad app for pilots. I was an early adopter and have been using it for years. The FAA even certified ForeFlight on my iPad as my EFB (electronic flight bag) so it’s actually not legal for me to conduct a Part 135 charter flight without it on board. I can’t say enough nice things about ForeFlight. It’s changed the way I plan flights and navigate while in flight. It’s also saved me hundreds of dollars every year on Garmin GPS updates for my panel-mount Garmin 430 GPS — indeed, it saves me enough to buy a brand new iPad with ForeFlight subscription update every two years if I want/need to. (I’m even thinking of pulling that 430, which cost a whopping $12K back in 2005, out of my panel.) And Foreflight isn’t satisfied to rest on their laurels and just rake in the dough like other aviation product makers do — ahem, Garmin? — they’re constantly improving and updating their app, adding features all the time. They even listen to feedback from users; when I complained that their flight planner wouldn’t let me plan a helicopter flight with less than 30 minutes of reserve fuel (the airplane minimum), they modified the software to allow helicopters flight plans with 20 minutes of reserve fuel, as allowed by the FAA.

Do you think I like ForeFlight?

Anyway, since ForeFlight came out, a bunch of copycats have followed it. Garmin makes one of them. (Too little too late, guys.) There were a few others in the vendor tent. I wasn’t interested in switching. I’m sure that none can offer any more helicopter-specific features than ForeFlight or save me any money. And who wants to learn a new app?

But the beauty of using a tablet for an EFB is that I could easily change apps if I wanted to without dumping a lot of money on new panel-mount hardware.

I chatted with a few vendors about a few products. Along the way, I learned that one vendor’s ADS-B solution wasn’t certified for helicopters because of vibrations (huh?) and that I could probably get an ADS-B transmitter/receiver that would work with my iPad and ForeFlight. Although all the vendors at the seminar had urged pilots to get their systems upgraded now because of long waits at avionics shops, it’s clearly in my best interest to wait. As time goes by, more and possibly better and definitely cheaper solutions are coming to market. I could spend $3,000 to $5,000 now or wait three years and spend $1,500 to $4,000 for something better that might be more powerful or smaller/lighter. That’s what I think, anyway. Time will tell.

Here’s Penny, sound asleep at the ADS-B seminar.

I had lunch at 11:00 and ate it at a table in the shade of the big main stage tent. It was getting hot outside, just as forecasted — a beautiful sunny day that would soon be in the 90s. I shared my hot dog with Penny, who gobbled it right up and looked for more. She’d been extremely well-behaved all day, snoozing on the floor or my lap in the seminar and letting me carry her in the more crowded areas of the vendor tent.

A speaker came on the stage at 11:15. It was an older female pilot who had made as an airshow pilot. She started her presentation with a story about her father, an airline pilot, who crashed his plane when a passenger went berserk and how much it meant to her when accident investigators determined it wasn’t his fault. It was a weird story and it really turned me off to whatever came next. I got the distinct impression that she’d been telling that story in front of every audience she’d addressed for the past forty years, vindicating her father every chance she got. I was done eating anyway, so I left.

I’d planned on going to the ForeFlight tips seminar at 11:15, but arrived at 11:30 to a standing room only crowd. There was no way I was getting inside the tent — people lined the outside of the seating area and flowed out the doors. I didn’t think I wanted to go in anyway. With poor ventilation in the tent, it had to be nearly 100° in there. I’d get my tips some other time.

“Grumpy,” coming in to park after a flight.

Instead, I went back to the vendor tent and chatted with the few vendors that were too busy to speak to on my first time through. Then I wandered around the airplane exhibits, chatted with a few pilots, and watched the B-25, “Grumpy,” take off with a bunch of passengers who’d paid $495 for the privilege.

The 12:45 seminar I chose was back at the main stage. It was led by AOPA’s media guy, who apparently makes videos related to flying. He showed a series of snort video productions about various pilots or aircraft. Although they were pretty good, his “Top 40 Radio Voice” narration didn’t always fit in and sometimes made me laugh.

An hour later, I was sitting closer to the front of the room in the same tent for Barry Shiff’s presentation, which consisted mostly of funny flying stories with photos. It was, in a way, a sort of aviation stand up comedy routine. Not laugh-your-ass-off funny, but extremely entertaining. Barry has had a long career in aviation and aviation writing and has gotten many opportunities to be part of many interesting projects. Am I alone in considering him a legend? I felt fortunate to have had the opportunity to chat with him the evening before.

I stayed in the tent for the start of the AOPA Pilot Town hall — the last event of the day — but it seemed too much like an airplane-specific commercial for AOPA membership than a chance to learn something. So Penny and I wandered back outside and killed time at vendor booths and watching the B-25 some more. When the Town Hall was over, we near the front of the line for the “ice cream social,” which was basically a bunch of volunteers handing out wrapped ice cream sandwiches and pops that had to be eaten very quickly.

And then it was over. AOPA staff members and volunteers had already begun taking video equipment and signs out of the seminar tents. Vendors began packing up. And the folks who had flown in began leaving.

The stats, available a few days later, were impressive for the event. Over 4,000 people attended, with 690 aircraft (that would be 689 airplanes and one helicopter) flying in and 162 campers. (I’m thinking the campers number is people and not planes, but it could be planes because there were a lot of us.) You can find a summary with some photos here. An AOPA photographer came by my site on Saturday morning to take a photo but I haven’t found it anywhere online yet.

Evening After the Event

Penny and I headed back to the helicopter. I attempted to feed her again and she again turned her nose up to it. She’d had some water during the day and had more when we got in. I sat in my chair in the shade, watching the parade of airplanes taxi by and then take off past me. About half the campers had packed up and left; the others seemed to be sticking around for another night like I was. A few people came by to chat and look at the helicopter.

Someone came by with a flyer for a party that would have a live band. Its location was a bit vague so when Penny and I tried to find it later on, we found a hangar party with no live entertainment that seemed to be wrapping up and a tiny gathering of people in front of a band that seemed to be practicing. Nothing that matched what was on the flyer. (In hindsight, I think it was the gathering by the band which was likely poorly advertised so it was poorly attended.)

Penny looks really tiny next to the front gear of a B-25.

I took some more photos of the classic airplanes sitting around, got yelled at for letting Penny off her leash, and then wandered over to the airport restaurant, leaving Penny tied up outside. (Penny is used to being left on her own when I go into a restaurant or someplace else she can’t go and is very well behaved when I have to leave her.) The place was crowded and I think the staff was overwhelmed. There was no air conditioning and the evaporative cooler I think they had running made the place kind of cool and steamy — if that’s even possible. I had a very unsatisfying meal, bought a plain hamburger for Penny, and headed back to camp. By this time, the sun was setting and I was ready to call it a day.

I remade the bed with my fleece sleeping bag zipped up and my top sheet folded inside it. This would provide two more layers between me and the ground. Then, after watching the sun set and the moon rise, visiting the blue building, and tidying up my camp in case the wind kicked up overnight, I crawled into the tent, got into my pajamas, and slipped into my sleeping bag. Penny curled up on her bed nearby. I read for a while and then fell asleep.

A Foggy Morning

Bremerton was IFR when I woke up the next morning. That means visibility was below minimums and it wasn’t legal to depart. Of course, helicopters can usually get a special VFR clearance, but what good would that do me if I couldn’t get to my next destination? Besides, I wasn’t in any hurry. As a matter of fact, I wasn’t quite sure where I was going to go.

My vestibule was large enough to set up my stove and make coffee.

After a visit to the blue building in the dreary predawn light, I staked out the front of my tent fly to create a little vestibule, moved my stove into it, and got the percolator going. A while later, I was drinking hot coffee while I caught up on social networking on my air mattress.

Outside, the other campers were beginning to stir. It was kind of wet outside — not the weather you’d want to be rolling up a tent in — so few were packing up. As the morning progressed, a few planes able to get IFR clearances took off into the gray sky. After a second cup of coffee, I got dressed, put Penny on her leash, and went back to the restaurant for breakfast. There were fewer people in there and both service and food were better. I had an egg scramble with bacon that was huge and brought back some for Penny. When I gave it to her back at camp, she turned her nose up to it, which got me worried because she hadn’t eaten much of the hamburger the night before either.

Back at camp, I made plans for departure. I’d originally thought I’d be bringing the helicopter to a children’s burn camp event in Bellingham, but the friend who’d asked me to do that had completely dropped the ball and hadn’t made any arrangements. (He later told me he’d been busy with a lot of other things. Whatever.) I was due to visit a friend in Salem, OR, but hadn’t planned to arrive until Monday and he wasn’t ready for me a day early. That meant Penny and I had a day to kill. With a helicopter.

I took my time packing up my camp. The weather was clearing slowly and there were pockets of visibility along the coast. I definitely wanted to be south of where I was by the end of the day, making my trip to Salem shorter instead of longer. But where to go? I did a bunch of research on my iPad and found an inn in West Port, WA, on the coast, that was walking distance from the airport there. They allowed dogs and had vacancy. I didn’t want to book a room until I was sure I could make it there, but there didn’t seem to be a problem on a Sunday night.

So with a destination in mind, I finished packing up my campsite, getting all my gear back into the rolling box and eventually back into the helicopter. A few of the folks I’d spoken to over the past day and a half stopped by to say goodbye. The weather had improved to the point where the airport was marginal VFR, so when I was ready to go, I started up the engine and warmed it up. Penny seemed to be happy in the co-pilot seat, curled up on her bed, already resting up for the next adventure.

It was just after 11 when I lifted off. Where was I going? For pie, of course! But that’s another story.

I’ve been writing for AOPA’s helicopter blog, Hover Power, for about a year and a half. Back in February 2016, they published the first of three articles about the contract work I do: “

I’ve been writing for AOPA’s helicopter blog, Hover Power, for about a year and a half. Back in February 2016, they published the first of three articles about the contract work I do: “