Well, it’s not quite what you might be thinking.

It’s true. I’ve become a migrant farm worker.

My original setup was pretty pitiful. I didn’t realize then how much time I’d be spending on the road.

It all started back in 2008 when I made my first annual migration from Arizona to Washington state to do agricultural work: cherry drying. I’d learned about the work two years before, but it took that long to be assured of a contract after the long migration. And one thing was for sure: I wasn’t about to move my helicopter, truck, and trailer 1200 miles (each way) without some guarantee of work on the other end.

It was a win-win situation for me. Escape Arizona’s brutal summer heat while earning some money with my helicopter, which would likely be parked most of the summer anyway. How could I turn it down?

The first season was only seven weeks long and I only flew 5 hours on contract. It was barely worth the travel time and expense.

In 2009, I picked up late season work in Wenatchee Heights.

But the next year was 11 weeks under contract and I’ve managed to get about the same every year. I’ve also managed to add contracts to the point where I now bring a second pilot in for 5 weeks and a third pilot in for about 10 days. Fly time varies, as you’d expect, with the weather. My goal is to have two pilots (including me) for at least 10 weeks and a third for a month.

The Work

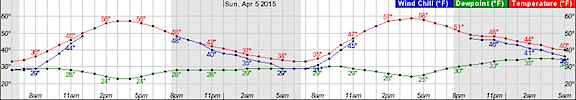

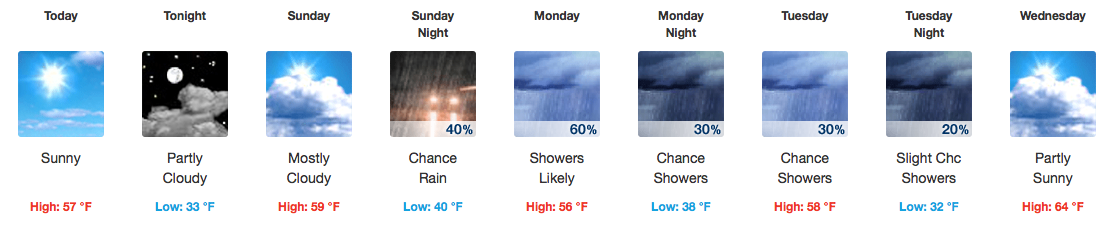

The work situation is unusual. I’m required to stay in the area for the entire length of the contract, on call during daylight hours seven days a week. No days off, no going home on weekends. On nice, clear days with 0% chance of rain, I can wander a bit from base, as long as I keep an eye on weather forecasts and radar. Still, day trips to Seattle (150 miles away) or off-the-grid locations were pretty much out of the question. Heck, I couldn’t even hike in parts of Quincy Lakes, less than 5 miles from my base, because there was no cell signal there.

One pilot I know was in Seattle when he saw the weather coming in on radar. He hopped in his truck and sped east. I don’t think he planned to have the truck break down an hour away. He hitchhiked in and got started on his orchards about the same time I was refueling to finish up mine. Not sure if he learned his lesson. He was back the following year playing the same risky games.

When rain is possible, things are different. I stay close — often at my base all day. If radar shows rain coming, I’ll go out and prep the helicopter for flight — make sure its full of fuel, preflight it, and take off the blade tie-downs or hail covers (whichever it’s wearing). If radar shows rain on one of my orchards, I’ll suit up and wait in my truck beside the helicopter. Then, when the call comes, I can be in the air in less than 5 minutes.

Cherry drying is all about flying low and slow.

The work itself is dangerous and requires good hovering skills in all conditions. I’m hovering just over the trees at low speed, firmly inside the Deadman’s Curve. If the engine quits, a crash through the trees is assured. Some orchards are hilly, others have obstacles like buildings and poles and wires. I can be called out as early as predawn and can be flying after sunset — I’ll fly as long as I can see a horizon.

The summer days in Central Washington State are long, with sunrise around 5 AM and sunset around 9 PM on the summer solstice. Because the night is only 8 hours long and I never really know whether I’ll be flying at dawn, there’s no alcohol, even at the end of a long day — remember: “eight hours from bottle to throttle.”

But the standby pay is good, compensating me not only for getting my helicopter into the area but keeping it there and assuring it’s available when called. It used to bother me when I got calls from tourists in Arizona wanting to see the Grand Canyon in July and I couldn’t take them because I was 1200 miles away. Then I realized that I was being paid for my time in Washington and knew that it was nicer to be paid to sit around and wait than to fly cheap midwesterners — who else visits Phoenix in July? — to a place I visited more times than most people can imagine.

Here I am with Penny the Tiny Dog last year after a cherry drying flight.

I did all the work myself: prepping the helicopter, flying, refueling, putting the helicopter to bed. I’d take the truck to the bulk fuel place in Ephrata or Wenatchee and fill my 82-gallon transfer tank with 100LL so I always had some on hand. I’d move, park, and move the RV as needed, dealing with all the hookups, including the often nasty sewer line. I’d handle propane tank refills and minor repairs. I’d also tend to the truck, making sure it got its oil changed with Rotella (as requested), even though it meant a trip to the Walmart in Chelan, 60 miles away. In the meantime, I handled all the client relations stuff, including getting clients signed up, visiting their orchards so I knew where hazards were, invoicing, and collecting fees.

In between, I managed to have a nice, easy-going life, making lots of friends and doing fun (albeit local) things.

The Logistics

The logistics of being a “migrant” worker were daunting. Each May I needed to get my helicopter and RV from Arizona to Washington. Each August or September, I needed to get them both back to Arizona. That meant a total of three round trips.

Here are all of Flying M Air’s assets: our helicopter, 1-ton diesel Ford Truck, and a 35-foot fifth wheel RV. It takes two trips for me to move them to a worksite.

I usually brought the helicopter north first, leaving it in Seattle for maintenance. Then I’d fly home on an airliner, hook up my RV to a truck, and make the 2-3 day drive north with my parrot, Alex the Bird. (Alex is gone now; he has a new home.) Then I’d take a flight from Wenatchee to Seattle and pick up the helicopter. With luck, I had decent weather and could come east through one of the passes: Snowqualmie or Stevens.

One time I had rotten luck and, after several aborted attempts to get over the Cascades, wound up flying all the way down to Portland and following the Columbia River through the Gorge. That was a costly ferry flight.

Later, I skipped the Seattle maintenance — saving a ton of money not only on ferry flying but maintenance itself; my Phoenix area mechanics seemed to be able to do the same work for a lot less money.

It was not fun cleaning this out of my helicopter.

The last time I left the helicopter behind while fetching the RV, during the week I was gone some birds built a nest in my helicopter’s fan scroll and engine compartment. That was quite a mess to clean up.

The drive up was an adventure, too. I tried all kinds of routes. The fastest was Route 93 from Wickenburg, AZ (where I lived at the time) to Twin Falls, ID and then Route 84 to the Tri-Cities area of Washington and back roads from there. It was a long drive. If I made it to Jackpot NV on the first day — 679 miles from home — I’d have a shorter drive the next day. But most times, I couldn’t do it on my own.

Once, I arrived at my Washington destination after sunset and faced the task of parking a 35-foot long fifth wheel trailer in a parking spot between two railroad ties. I still don’t know how I did it in the gloomy light after driving more than 600 miles that day.

In August or September, I did the same thing in reverse. Take the RV home with my parrot, then fly back on an airliner to fetch the helicopter.

In 2009, my wasband and our dog Jack accompanied me on the return RV drive. My wasband was between jobs and it seemed like a great opportunity to enjoy a late summer trip — we so seldom had real vacations together. We went east to Coeur d’Alene, ID, where a friend of mine lives, then kept going and visited Glacier National Park. We camped there and in Yellowstone. Then, for reasons I can’t quite comprehend, my wasband was in a big hurry to get home, cutting the vacation short by at least a week over what we could have done.

My wasband also occasionally accompanied me on the helicopter flight. I think he did it twice with me. Once, we flew from Seattle to Page, AZ. Another time, we flew from Seattle down the coast until the marine layer forced us inland. I thought he enjoyed those flights, but apparently he considered them “work” — during our divorce trial, he claimed he was working for me to fly the helicopter back. Not likely, since he wasn’t a commercial pilot and wasn’t legal to work as one. Maybe if I’d charged him for the opportunity to build flight time — as I charged every other pilot who flew that trip with me — he would have seen it differently. To me, however, it was just another helicopter “road trip” with the man I loved.

Silly me.

I wonder who’s helicopter he’s flying these days.

Today’s Migrant Farm Work

I started frost control — another kind of agricultural work — last year.

I went to HeliExpo last year in Las Vegas during frost season and stayed at the Cosmopolitan, with an excellent view of the strip from my room.

My contract required me to put my helicopter in California, but didn’t require me to stay with it. Instead, I’d be paid generously for callouts and standby time. I moved it to the Sacramento area in late February and spent the following two months traveling between Phoenix and Sacramento, Wenatchee, and Las Vegas, spending most of my time in Arizona packing up my belongings for my move to Washington later in the year.

The contract terms weren’t good unless there was frost — and there wasn’t any last year. I just about broke even when you consider my investment in additional lighting for the helicopter and the cost of repositioning it and my RV. But at least I got my foot in the door as a frost pilot and got to see what it was like flying over almond trees in the dark.

Can’t say I liked it.

I moved to Washington in the spring, when the divorce proceedings were over and I’d relinquished exclusive use of my house to my wasband and his chief advisor — the woman who’d apparently convinced him to spend more than $100K to go after my money. (Seriously. I can’t make this shit up.)

I was still “migrant” for a while — I started in Quincy and moved to Wenatchee Heights, just as I’d done the previous five years. But when that late season contract was over, I moved to my future home, a 10-acre parcel of view property overlooking the Columbia River Valley and Wenatchee. It looked as if my migrant farm worker days were over — I could commute from my new home to my clients’ cherry orchards.

The almond trees are beautiful when they’re blooming — and they smell nice, too!

I had no intention of doing frost control work under the same contract as last year. But I didn’t have to. I got a much better contract — one that paid better if I didn’t fly. With winter dumping snow on my home in Washington, I moved the RV and later the helicopter down to the Sacramento area again, setting up camp at a small local airport in a nice farming community. With rent at a startlingly low rate of only $200/month with a full hookup, the season would be very profitable even if I didn’t fly.

Best of all, I like the area: the weather was warm, the town was full of great restaurants (and even a beekeeper supply place), there was a nice dog park for Penny the Tiny Dog, and Sacramento was only 20 minutes away. I had a friend in Carmichael, only 30 minutes away, and more friends in Georgetown and Healdsburg, each only 90 minutes away by truck — or 30 by helicopter.

Frost is different from cherries. With frost work, you seldom fly during the day. Instead, you fly any time between 2 AM and 8 AM — most often right around dawn when it’s coldest. That means you have the whole day to do anything you like — hiking, bicycling, kayaking, wine tasting, whatever. As I write this, I’m planning a spa day in Geyserville, a trip to San Francisco, and at least one wine tasting trip to Napa Valley. I’ve joined a few local meetup groups and will be hiking and kayaking with new friends. All while “working” — or at least being paid to stand by in case it gets cold.

It’s almost like a paid vacation — with the added bonus of being able to build night flying time.

It’s a Living

My agricultural work has been very good to me. It saved my business from failure and has made it possible for me to save up enough money for the helicopter’s overhaul.

Once my home is built and my possessions are stored away inside it, I can go back to a modified version of my earlier plan: eight months out of the year flying frost and cherries in in the Sacramento and Wenatchee areas and four months goofing off. But instead of hanging around my old house in an Arizona retirement community with a bunch of seniors, I’ll travel and actually see some of the world on my own terms.

It’s the semi-retired lifestyle I’d expected at this stage of my life, delayed about two years by my wasband’s inexplicable greed and stupidity, and enjoyed without the company of a sad sack old man.

I’ve been writing for AOPA’s helicopter blog, Hover Power, for about a year and a half. Back in February 2016, they published the first of three articles about the contract work I do: “Doing Wildlife Surveys“. The other two articles were in the queue, but never appeared.

I’ve been writing for AOPA’s helicopter blog, Hover Power, for about a year and a half. Back in February 2016, they published the first of three articles about the contract work I do: “Doing Wildlife Surveys“. The other two articles were in the queue, but never appeared.