There are some things you really wish you could share.

The panic started on Friday. That’s when I checked my helicopter’s log books and realized that instead of 14 flight hours until a required 100-hour maintenance, I had under 5 hours. Once that 5 hours expired, if I flew for hire — even for cherry drying flights conducted under FAR Part 91 — I risked the possibility of having my Part 135 certificate put on hold (or worse) and losing insurance coverage for my helicopter due to my failure to follow the manufacturer’s maintenance schedule.

I did not want that to happen.

I started working the phones. First, I asked my mechanic to come up from Phoenix. I got a “maybe,” which really wasn’t good enough. I talked to a number of other operators about using their mechanics but kept running into a problem with the required drug testing program. Finally, I called the folks at Hillsboro Aviation — which happens to be the dealer that sold me my helicopter back in 2005 — and talked to John. He said that if I could get it in to him when they opened at 8 AM on Tuesday morning, there was a chance that they could have it ready by day’s end.

The weather, of course, was of vital importance. I was in Wenatchee for cherry drying season; if there was any possibility of rain, I could not leave. I did have two other pilots on duty to cover my contracts, though, so unless it rained everywhere at once, they could handle it. And fortunately, the forecast had 0% chance of rain for the upcoming week.

I packed a light bag on Monday night: some spare clothes and toiletries (in case an overnight stay was required), dog food and a dish for Penny the Tiny Dog, and my log books. And on Tuesday morning, at 5:30 AM, I preflighted, packed up the helicopter, set up the GoPro Hero 2 “nosecam,” secured Penny in the front passenger seat so she couldn’t get into the controls, started up, and took off.

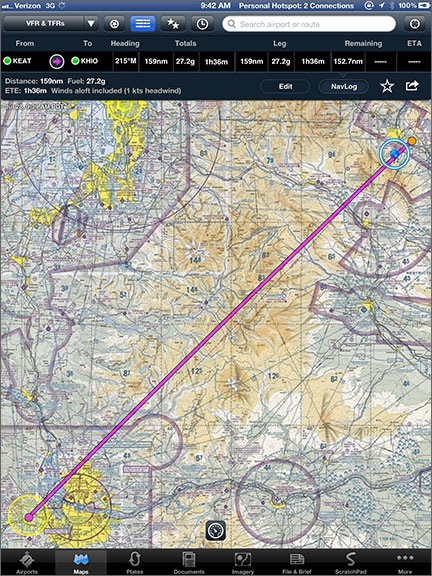

My direct route, on Foreflight.

My goal was to complete the flight as quickly as possible — that meant a direct route across the Cascade Mountains. My flight path would take me over Mission Ridge, across I-90 west of Ellensburg, and into the Cascades south of Mt. Rainier and north of Mt. Adams. Along the way I’d have to climb to just over 7,000 feet, fly over miles of remote wilderness area, and pass right by Mt. St. Helens. The whole flight was 159 nautical miles (183 statute miles) and would take just over 90 minutes.

I’d flown over the Cascades — or tried to — about a dozen times in the past five years. Weather had almost always been an issue. On several occasions, low clouds in the mountain passes at I-90, Route 2, or Route 12 made it impossible to get through. Other times, I had to do some serious scud-running, darting from one clear area to the next to find my way across. Still other times, I was forced to fly above a cloud layer until I found a “hole” in the clouds where I could slip back underneath on the other side of the mountains. I can only remember one time when scattered clouds were high enough to make the flight as pleasant as it should be.

The weird thing about the Cascades is that you can’t see what the cloud cover is like there until you’re airborne and have cleared the mountains south of Wenatchee. The clouds don’t show up on radar or weather reports unless it’s raining. So you might have a perfectly beautiful day in Washington’s Columbia River basin but the Cascade Mountains could be completely socked in with thick clouds. It’s actually like that more often than not — at least in my experience.

So despite the fact that it was a beautiful day, I was a bit concerned about the weather.

Until I passed over Mission Ridge, just south of Wenatchee. I immediately saw Mt. Rainier and Mt. Adams in the distance. Seeing these two mountains — the whole mountains, not just the tops poking up through clouds — was a very good sign.

Penny immediately curled up on her blanket on the front passenger seat and went to sleep. This really surprised me. It was the first time she’d been in a helicopter and she seemed completely unconcerned about it. I guess that was a good sign, too.

And so began one of the most beautiful flights I’d ever had the pleasure of doing in my helicopter.

The top of Mission Ridge and beyond.

I crossed Mission Ridge, which was glowing almost orange in the first light of day and headed southwest along the straight line my GPS indicated to Hillsboro, OR. I drank in the scenery spread out before me: the windmill-studded valley around Ellensburg, the rolling pine forests cut with stream and river beds, the snowcapped granite ridges. At one point, I had Mt. Rainier off my right shoulder, Mt. Adams and Mt. Hood to my left, and Mt. St. Helens right in front of me. I felt like a tiny speck suspended in the air, the only person in the world able to see just what I was seeing. I felt small but all-seeing at the same time.

When I first caught sight of a fog-filled valley at the base of Mt. Rainier I began to realize that weather might still be an issue. Soon, I was flying from one pine-covered ridge to the next, over what looked like a sea of white foam. No VFR pilot likes to lose sight of the ground and I admit that I flew with some fear. An engine failure would leave me nowhere safe to land — if I tried to land in one of the valleys, I’d likely hit the ground before I saw it through the fog.

But the beauty of what was around me somehow made it okay. I thought to myself, if this is my time to go, what better place and way to end my life? Doing what I love — flying through amazing scenery — what else could anyone ask for? And then all the fear was gone and I was left once again to enjoy my surroundings.

Flying across this ridge was the highlight of my flight.

I also felt more than a bit of sadness. There’s no way I can describe the amazing beauty of the remote wilderness that was around me for more than half of that flight. And yet there I was, enjoying it alone, unable to share it with anyone. Although I think my soon-to-be ex-husband would have enjoyed the flight, he was not with me and never would be again. I felt a surge of loneliness that I’ve never felt before. It ached to experience such an incredible flight alone, unable to share it firsthand with someone else who might appreciate it as much as I did.

I can’t begin to say how glad I am that the GoPro was rigged up and running for the whole flight. At least I have some video to share.

Yale Lake near Cougar, WA, just southeast of Mt. St. Helens.

As I descended down the southeast slope of Mt. St. Helens, leaving the Cascades behind me, I crossed over a small lake with a scattering of clouds at my level. As I glided through them and back into civilization, I felt as if the magical part of the flight was over. Indeed, the rest of the flight was rather routine, passing over rolling hills, farmland, highways, and rivers. A marine layer hung low over the Portland area and I squeezed under it, called the tower at Hillsboro Airport, and landed on the ramp at my destination. It was about 7:30 AM.

Penny at the beach. She seems to like sand almost as much as grass.

The folks at Hillsboro Aviation were great. Although they didn’t finish up that day, the helicopter was ready to go at 9:30 AM the next morning. Penny and I had spent the night in Rockaway Beach, where Penny got to run through the sand and tease the other beach walkers with her antics.

We left Hillsboro at around 11 AM on Wednesday. It was a cloudless day — even the valley fog was gone. But the harsh midday light washed away much of the beauty of the scenery; the GoPro video from the return flight isn’t much to look at. We were back on the ground at our base in Wenatchee Heights before 1 PM, ready for another 100 hours of flight.

A week or two ago, I got an email message from a reader who had read my November 2011 post, “

A week or two ago, I got an email message from a reader who had read my November 2011 post, “ Charts, by the way, make it very easy to identify these areas. They’re normally surrounded by a blue line that has dots on the inside of the area. This entry from the

Charts, by the way, make it very easy to identify these areas. They’re normally surrounded by a blue line that has dots on the inside of the area. This entry from the