The best dog.

Our first exposure to Jack was in mid 2001. The year before, we’d put our 14-year-old Dalmation to rest after a life of controllable health problems became uncontrollable with age. He was my third dog — my family always had dogs — and my husband’s first. His loss was shattering and we took some time off to see if we could live without a dog in our lives.

Nine months later, we were thinking of trying again. We’d decided that we wanted a smart dog. While Spot had been smart enough to fetch the newspaper from the curb, fetch my slippers, and distinguish one toy from another by name, he wasn’t quite smart enough to stay out of the Arizona sun or avoid the back end of a protective mare when a newborn filly was in the area. I didn’t think Dalmatians could fly, but ours did. He was never quite the same after that, either.

We’d been talking to people about dogs and learning about different breeds well-suited for ranches. I’d decided that something like a border collie or Australian shepherd would be a good breed. So when the newspaper mentioned a border collie/Australian shepherd mix up for adoption, we decided to take a look.

We’d been talking to people about dogs and learning about different breeds well-suited for ranches. I’d decided that something like a border collie or Australian shepherd would be a good breed. So when the newspaper mentioned a border collie/Australian shepherd mix up for adoption, we decided to take a look.

Understand that Wickenburg is a small town and nothing much happens. In order to fill the pages of the local weekly rag they call a newspaper, they’d often show photos of pets up for adoption. (I don’t know if they still do this. We stopped reading the crap they printed when they became the propaganda arm for a corrupt mayor and Chamber of Commerce.) The town didn’t have a Humane Society back then, so all unwanted pets were brought to Bar S Animal Clinic, which happened to be the vet we used for Spot and our horses.

The story we got about the dog — who was already named Jack — was that he’d been owned by a family that neglected him. He was frequently out loose and had been picked up by the local dog catcher at least three times. The first few times, the family paid the fee and picked him up. But the last time, they’d decided not to. He was up for grabs. They figured he was 9 to 12 months old.

The newspaper clipping completely understated his personality. When they brought him out to the waiting area at Bar S for us to meet him, they practically had to drag him out on a leash. He was terrified. He didn’t want to come to either one of us.

Although he looked like a nice enough dog, I had doubts. I didn’t want a dog that was afraid of his own shadow. Mike and I talked it over and then talked to the folks at Bar S. I distinctly remember asking if we could bring him back if it didn’t work out. They told us we could, so we coaxed him outside to the car.

That’s when we noticed Jack was really different. He wouldn’t get in the car — it was like he didn’t know how. Finally, I sat in the front seat and Mike put him on my lap. He closed the door and we headed back to the office in town.

In those days, I owned a condo in downtown Wickenburg. After dealing with the last set of abusive and destructive tenants, I’d decided to turn the place into an office for us. I had the living room, Mike had the master bedroom. Our home was across town, about 5 miles away by car.

The condo was on the second floor. That’s when we discovered that Jack didn’t know how to climb steps.

His first gift to us was a big poop on the living room carpet.

He started coming around to us very quickly and that scaredy-dog personality faded away. He listened, came when we called him, and didn’t need to be on a leash around the yard. He also seemed to get along fine with the horses. And he understood what shade was.

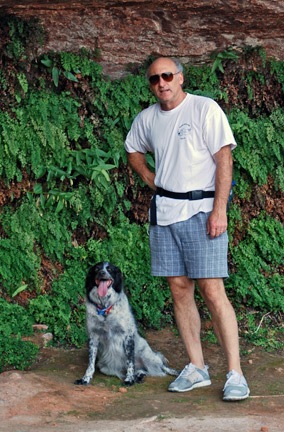

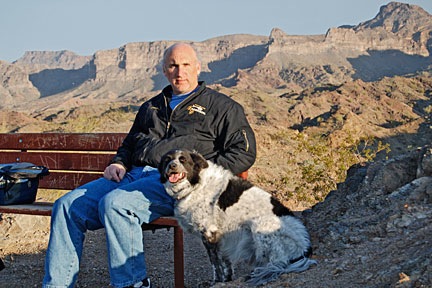

He bonded to me — probably because he’d been sitting on my lap on that car ride. This was not ideal. I’d planned to get a parrot in a month or so and Jack was supposed to be mostly my husband’s dog. So for the first few days, I began ignoring him and Mike started lavishing him with attention. After a few days of that, he was Mike’s dog, although he responded to me equally well. But when we were together, it was always Mike that he went to first. That was fine with me.

He bonded to me — probably because he’d been sitting on my lap on that car ride. This was not ideal. I’d planned to get a parrot in a month or so and Jack was supposed to be mostly my husband’s dog. So for the first few days, I began ignoring him and Mike started lavishing him with attention. After a few days of that, he was Mike’s dog, although he responded to me equally well. But when we were together, it was always Mike that he went to first. That was fine with me.

We’d had him about a month when he fell out of the back of Mike’s pickup on the way to the office. It wasn’t light yet — Mike was telecommuting for a job on the east coast back then and would routinely get to the office around 6 AM local time. He wasn’t sure where Jack had fallen out, but he was able to narrow it down to a 1/2 mile stretch of road about a mile from our house.

We spent the entire day looking for him, calling the dog catcher, Bar S, and any other group that might know something about a found dog. I used my Jeep to drive up and down all the sandy washes in the area, calling him by name. We were convinced that he’d been injured and was hiding in the bushes somewhere, possibly dying.

When night fell, we knew the coyotes would get him. We were shattered. In just a month, we’d grown to love him.

At 3 AM, Mike climbed out of bed, unable to sleep. He came downstairs to get a glass of water. And who was at the back door, waiting to be let in? Jack. I don’t know how he spent his day, but he found his way home, safe and sound.

The next nine and a half years left indelible memories on my mind:

Jack sitting on the edge of the back patio, watching the road that leads down to our house, racing around to the front when Mike’s car or truck rolled down.

Jack sitting on the edge of the back patio, watching the road that leads down to our house, racing around to the front when Mike’s car or truck rolled down.- Jack barking at the UPS truck or FedEx truck before it even came into sight, climbing into the open UPS truck door as I chatted with the driver and he fetched my package, accepting cookies from our mail carrier.

Jack running around on our 40 acres in northern Arizona, chasing rabbits, crawling under the shed, looking for mice and rats.

Jack running around on our 40 acres in northern Arizona, chasing rabbits, crawling under the shed, looking for mice and rats.- Jack barking at the sound of coyotes, close or far, sometimes in the middle of the night.

- Jack chasing lizards in the backyard and, more than once, catching them.

- Jack riding in the back of my Jeep as we explored the old forest roads just south of the Grand Canyon or out in the desert along Constellation Road or up in the Bradshaw Mountains.

- Jack “herding” the horses up the driveway at the end of the day, dodging Jake’s hoofs as he tried to kick him.

Jack hiking with us up Vulture Peak, through the Hassayampa River bed, at Granite Mountain, inside Red Mountain, at the Grand Canyon, in the forest at Mount Humphreys, in countless other places.

Jack hiking with us up Vulture Peak, through the Hassayampa River bed, at Granite Mountain, inside Red Mountain, at the Grand Canyon, in the forest at Mount Humphreys, in countless other places.- Jack in the back of my helicopter, looking out the window as we flew over town.

- Jack on the trail in the desert as we followed on horseback, watching him take off with high pitched yipping sounds as he closed in on a jackrabbit or cottontail.

Jack riding in the back of the pickup, his head out in the slipstream as we drove around town. (He only fell out of the pickup that one time, although he did fall out of my Jeep twice.)

Jack riding in the back of the pickup, his head out in the slipstream as we drove around town. (He only fell out of the pickup that one time, although he did fall out of my Jeep twice.)- Jack playing with my neighbor’s dogs, who used to come visit for cookies and attention.

- Jack racing around the side of the house when he knew we’d be coming out the front, looking at us with the “Can I please come?” face and racing to the truck when we said yes.

- Jack whining when we prepared to leave and told him he’d have to stay in. It’s that whine that Alex the Bird picked up and mimics to this day.

- Jack meeting us at the door as if he hadn’t seen us for years when we came home from a day out.

- Jack ignoring Alex the Bird when he whistled Mike’s whistle or issued commands: “Hey, Jack!” “Go lie down!” “Go outside!”

- Jack on his dog bed at the foot of the bed, or by the open french doors in our bedroom, or on a rug on the floor of our cabin or RV while we slept.

- Jack trotting along ahead of us, on his extension leash, as we walked the few blocks from our Phoenix condo to Wildflower Bakery for morning coffee and breakfast croissant.

I could go on all day, listing the snapshots in my mind. Jack didn’t have a mean bone in his body. Everyone loved him.

He never seemed to slow down — until recently. In the 20-20 vision of hindsight, I should have realized there was a problem. I noticed about a month ago that he seemed to be breathing heavily, even at rest, once in a while. I mentioned it to Mike, but he didn’t notice.

Last weekend, he seemed a bit under the weather, spending more than the usual amount of time just lying around. We thought it had something to do with his food; Mike had bought something new. Jack had a sensitive digestive system and could only eat dog food. (People food literally made him sick — even good stuff like steak!) But by Sunday, he was back to his old self.

On Monday morning, Mike went on a business trip to Georgia.

Jack stopped eating on Tuesday. I took him to the local vet on Wednesday and Thursday mornings. He had blood work. He spent Thursday at the vet. His labored breathing prompted the vet to take an X-ray. That’s when he saw the fluid around his lungs.

I took him to another vet in Peoria for an ultrasound on Friday morning. By that time, he had to be carried everywhere. He was alert but weak, struggling to breathe.

The ultrasound picture made the problem obvious. The doctor was able to diagnose in less than a minute. Jack had a large tumor on his heart. It looked to be about 1/5 the size of his heart, so it had obviously been growing there for a while. The tumor was causing fluid to leak into the sac around his heart. That fluid was crowding out his lungs, making it difficult to breathe.

The tumor, because of its placement, was inoperable. Chemotherapy was not usually effective — although I admit that I don’t think we would have gone that route. Draining the fluid could buy him a few hours or days, but his condition would come right back to the way it was. There was even a chance that the fluid could fill as quickly as it was drained.

In other words, Jack was terminally ill and likely had a very short time to live.

The decision wasn’t hard. The worst thing you can do for an animal is try to keep it alive when it’s suffering. Jack, although maybe not in pain (yet), was laboring to breathe. It was taking everything he had. He couldn’t even walk anymore. He hadn’t eaten in more than three days. His condition was deteriorating quickly. I wasn’t even sure if he’d be alive when my husband came home that night.

The decision wasn’t hard. The worst thing you can do for an animal is try to keep it alive when it’s suffering. Jack, although maybe not in pain (yet), was laboring to breathe. It was taking everything he had. He couldn’t even walk anymore. He hadn’t eaten in more than three days. His condition was deteriorating quickly. I wasn’t even sure if he’d be alive when my husband came home that night.

After breaking the news to my husband, I did what I needed to do. The folks at Bar S Animal Clinic were unbelievably kind to both Jack and me. I cannot thank them enough.

Jack’s gone now and we’ll miss him. He was the best dog ever.

Note: I’ve closed the comments on this post in an effort to head off condolences, etc. While I appreciate any kind thoughts you might have in this difficult time, I believe that reading them will only prolong my grief. If you want to leave a comment, instead consider a small donation to your local Humane Society. And the next time you want to add a pet to your life, visit the local pound or Humane Society first. If you’re as lucky as we were, you’ll get to take home a pet as wonderful as Jack was.

Jack sitting on the edge of the back patio, watching the road that leads down to our house, racing around to the front when Mike’s car or truck rolled down.

Jack sitting on the edge of the back patio, watching the road that leads down to our house, racing around to the front when Mike’s car or truck rolled down. Jack running around on our 40 acres in northern Arizona, chasing rabbits, crawling under the shed, looking for mice and rats.

Jack running around on our 40 acres in northern Arizona, chasing rabbits, crawling under the shed, looking for mice and rats. Jack hiking with us up Vulture Peak, through the Hassayampa River bed, at Granite Mountain,

Jack hiking with us up Vulture Peak, through the Hassayampa River bed, at Granite Mountain,  Jack riding in the back of the pickup, his head out in the slipstream as we drove around town. (He only fell out of the pickup that one time, although he did fall out of my Jeep twice.)

Jack riding in the back of the pickup, his head out in the slipstream as we drove around town. (He only fell out of the pickup that one time, although he did fall out of my Jeep twice.)