A note in response to a bulk email from an old colleague.

It may be hard for some blog readers to believe, but for a while in the late 1990s and early 2000s, I was “famous.”

My fame was limited to a group of people who bought my books and read my articles about using computers. I started writing in 1991 — as a ghostwriter for a John Dvorak book — and was soon writing my own titles. I learned early on that if you couldn’t write a bestseller, you had to write a lot of books. So I did. And then, in the late 1990s, two of my books became best sellers. Subsequent editions of the same book continued to be best sellers. For a while, I was making a very good living as a writer. At the computer shows where I was a regular speaker, people actually asked for my autograph.

I’m not an idiot. I knew that my good fortune could not last forever. So as I continued to write, turning out book after book and becoming well known in my field, I invested my money in my retirement, assets that could help extend (or at least securely bank) my wealth, and something that I thought would be a great hobby: flying helicopters. I learned to fly, I got hooked on it, and I bought helicopter. I started my helicopter charter business in 2001 — it was easy to fit flights in with my flexible schedule as a writer — and bought a larger helicopter in 2005. Building the business was such a struggle that I honestly didn’t think I would succeed. But fortunately, I did.

My most recent book was published back in 2012. I don’t call it my “last book” because I expect to write more. They likely won’t be about computers, though.

And it was a good thing, because around 2008, my income from writing began declining. By 2010, that income began going into freefall. Most of my existing titles were not revised for new versions of software. Book contracts for new titles were difficult to get and, when they were published, simply didn’t sell well.

Around the same time, my income from flying started to climb. Not only did it cover all the costs of owning a helicopter — and I can assure you those costs are quite high — but it began covering my modest cost of living. By 2012, when I wrote my last computer book, I was doing almost as well as a helicopter charter business owner as I’d done 10 years before as a writer. And things continued to get better.

I was one of the lucky ones. Most of my peers in the world of computer how-to publishing hadn’t prepared themselves for the changes in our market. (In their defense, I admit that it came about quite quickly.) Many of these people are now struggling to make a living writing about computers. But the writing is on the wall in big, neon-colored letters as publishers continue to downsize and more and more of my former editors are finding themselves unemployed. Freelance writers like me, once valued for their skill, professionalism, and know-how, are a dime a dozen, easily replaced by those willing to write for next to nothing or even free. Books and magazine articles are replaced by Internet content of variable quality available 24/7 with a simple Google search.

So imagine my surprise today when one of my former colleagues from the old days sent me — and likely countless others — a bulk email message announcing a newsletter, website, and book about the same old stuff we wrote about in the heydays of computer book publishing. To me, his plea came across as the last gasp of a man who doesn’t realize he’s about to drown in the flood of free, competing information that has been growing exponentially since Internet became a household word.

I admit that I was a bit offended by being included on his bulk email list simply because he had my email address in his contacts database. But more than that, I was sad that he had sunk so low to try to scrape up interest in his work by using such an approach. Hadn’t he seen the light? Read the writing on the wall? Didn’t he understand that we have to change or die?

So after unsubscribing from his bulk mail list, I sent him the following note. And no, his name is not “Joe.”

The world’s a different place now, Joe.

After writing 85 books and countless articles about using computers, I haven’t written anything new about computers since 2012. I’m fortunate in that my third career took off just before that. Others in our formerly enviable position weren’t so lucky.

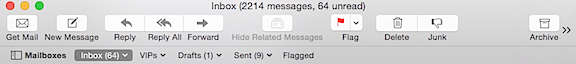

Not enough people need us as a source of computer information anymore. All the information they could ever want or need is available immediately and for free with a Google search. There are few novices around these days and only the geekiest are still interested in “tips.” Hell, even I don’t care anymore. I haven’t bought a new computer since 2011 and haven’t even bothered updating any of my computers to the latest version of Mac OS. My computer has become a tool to get work done — as it is for most people — a tool I don’t even turn on most days.

Anyway, I hope you’re managing to make things work for yourself in this new age. I’m surprised you think a newsletter will help. Best of luck with it.

And if you ever find yourself in Washington state, I hope you’ll stop by for a visit and a helicopter ride. I can’t begin to tell you how glad I am that I invested in my third career while I was at the height of my second.

Maria

Is it still possible to make a living writing about computers? For some of us, yes. But we’ll never be able to achieve the same level of fame and fortune we once achieved. Those days are over.

Yesterday afternoon, I got a call from a number I didn’t know and answered as I usually do: “Flying M, Maria speaking.”

Yesterday afternoon, I got a call from a number I didn’t know and answered as I usually do: “Flying M, Maria speaking.”