A quick story about a visit to a bookstore.

Yesterday, I spent much of the afternoon in Ellensburg, WA. Although less than 30 air miles from my home, it’s a 77-mile drive that takes about 90 minutes. Needless to say, I need to have a reason to go there when I do and I want to make the most of my time while I’m there.

Yesterday’s mission was to check out a gallery where I hope to show and sell my jewelry. That part of the trip went reasonably well, despite the fact that the person I needed to see was not there. It also led to me checking out a nearby museum that might also be a good place to sell my jewelry and two shops that I didn’t think were a good match at all.

I listen to NPR (National Public Radio). Say what you will about “liberal media” but NPR’s shows are intelligent, thoughtful, and informative. The local station, which goes by the name of Northwest Public Broadcasting (NWPB), is turned on in my kitchen almost all day every day. One of its sponsors is a bookstore in Ellensburg — the town apparently has at least three — and since I’m normally a bookstore lover and want to support NPR, I thought I’d go check it out.

I first went into the wrong bookstore, which was small but neatly stocked with new books, cards, journals, and gift items of interest to readers and writers. I wound up buying a book about vegetable gardening that basically provides a calendar-based schedule for garden tasks. (I hardly ever walk out of a bookstore empty-handed.)

I was actually leaving town when I caught sight of the bookstore that actually supported NWPB. I parked and went in.

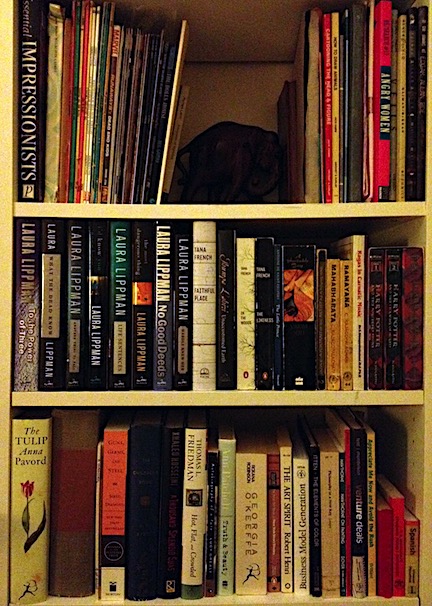

Browsing disorganized old books might be fun if you have an unlimited amount of time and the place is air conditioned. Or maybe not even then. (And no, this photo is not from the bookstore I visited. It’s a stock image from MorgueFile.)

This was not at all what I expected. The space was larger than the other shop but it was mostly full of dusty used books. I admit to flashing back to a used bookstore I used to visit in the 1980s way down near the financial district of Manhattan. That shop was smaller, more crammed, and dustier. Walking into this shop was like walking into the disorderly garage of someone who happened to collect old books. I realized immediately that there would be nothing of interest to me there, but I figured I’d give it a browse.

The guy behind the counter looked exactly like a stereotypical gamer or computer hacker. Perhaps in his 30s, he looked as if he might live in his mother’s basement, where he spent way too much time interacting with a computer screen. He asked me if I was looking for anything in particular and I told him I was just checking the place out because I’d heard about it on NPR.

“I remember when the lady from NPR came over,” he said. “The bookstore across the street used to be a sponsor. She came over here and told us he didn’t want to support the liberal media anymore. So she asked if we’d take his spot and my dad was here and said we would.”

I hadn’t seen the bookstore he referred to. The one I’d gone to was on another block.

As I looked at the old books, I got a bit of a brainstorm. Years ago, for my birthday or Christmas or some other gift-giving occasion, my wasband had bought me two Mark Twain first editions. He’d remembered me saying that I wanted to build a library of “nice quality books,” and thought (for some reason) that meant expensive first editions. So he’d gone to a bookstore probably a lot like the one I knew in lower Manhattan, and had bought two books that may have cost him hundreds of dollars. Book that looked just as old and dusty as the ones all around me that afternoon in Ellensburg, books I was afraid to open because I might damage them.

I wanted very badly to sell them but didn’t know of any bookstores that bought and sold collectors items.

This one might. So I asked if they ever bought first editions.

The shop guy seemed to search the database in his head for an answer. “Well, it depends on the topic and whether it’s in demand and — ”

“Mark Twain,” I said, trying to cut to the chase.

“You want to buy them?” he asked, obviously not understanding what I was getting at.

“No, I want to sell them.”

He looked uncomfortable.

“I don’t have them with me,” I said.

He relaxed.

“How about if I send you more information about them and you let me know. I can send titles and dates and photos of the covers and title pages. Just give me your card and an email address.”

“Okay,” he said. And he went back to his desk. I assumed he was getting a card.

I browsed. The book sections did have labels on them, but the books within each section were not in any order at all. So, for example, when I checked out the Art section, topics bounced from photography to painting to crafts to photography to architecture to painting… You get the idea.

It was taking a long time and the shop was hot. There was no air conditioning and it was nearly 100°F outside. When I left a little while later, I realized that it was cooler outside than inside.

I wandered back to the desk. He was writing something at the bottom of a sheet of notebook paper. It was taking a long time.

“All I need is your email address,” I said.

“Well, I’m just trying to redo the website right now,” he said. “I want to set it up so I can update it and it won’t cost so much money. So I’m putting in these forums and I want to use that for company communication.”

“You don’t have an email address?”

“Well, I do but on GoDaddy, I have to go through all these screens to get to it and they keep trying to sell me stuff and it takes a really long time.”

“Can’t you just set up Outlook or Apple Mail to access your email account?”

He looked up as if I’d just told him that it was possible to use a microwave to boil water right in a coffee cup. “Maybe I could,” he said slowly. I could see the dim lightbulb over his head getting slightly brighter.

Meanwhile, although I was wearing a thin cotton dress I was sweating like a pig. I wanted out of there but I didn’t want to be rude. “Just give me your website address,” I said, holding out my hand.

He went back to writing. About a minute later, he ripped off the bottom of the page and handed it to me. There were five lines: the bookstore’s name, the bookstore’s phone number, the bookstore’s complete street address (minus zip code), an email address, and the complete URL for the bookstore. He had basically hand-written a business card.

I took it, thanked him, and headed for the door otherwise empty-handed. “I just gave out my last business card,” he said to my retreating figure.

“I’ll email you with the book information,” I told him. And I walked out into the relief of a hot breeze.

Much later — this morning, in fact, as I looked over the torn-off notebook sheet I took out of my pocket — I thought about the death of bookstores. Unless this one had a solid client base, it wasn’t long for this world. How could it be? Not only did it have to compete against Amazon, the bane of all bookstores, but it had to compete against bookstores that actually had a clue about how to draw shoppers in, display a variety of interesting products, and sell things other than dusty old books.

Will I email him about my Mark Twain books? Heck, why not? You never know. I sure hope he tries Outlook for email because there’s no way in hell I’m going to participate in one of his forums.

—

Postscript: In searching the web for a public domain image I could use with this blog post, I stumbled across this article on Narratively: “Dear Dusty Old Bookstore.” If you have a greater love for old bookstores than I apparently do, you owe it to yourself to read it.