I try to define the concept of artisan goods and why they should be valued more than manufactured goods.

I have been dabbling in physical artistic endeavors — as opposed to writing, which is an intellectual artistic endeavor — for about six years now, when I started making jewelry from the rocks I began acquiring at the Arizona rocks shows I attended every winter. It wasn’t long before I got to the point where I wanted to sell what I made. The best way to sell art is either in a shop or at an art show. I didn’t have (or want) a shop so I started hunting down shows.

Art Show Tests

Art shows can be juried or non-juried. A juried art show is one where you need to provide details, samples, and/or photos of your work and the process of making it. A panel of people who are supposed to know what they’re doing and seeing judge whether your work is good enough for their show.

In general, artists want to be in a juried show because they will be among other artists who have passed the same test. Quality work means a quality show which also means buyers who are interested in quality work. It also makes a level playing field for the artists who participate.

One of the things art shows ask about when you apply is what percentage of your work contains manufactured items. For example, for jewelry you might use manufactured ear wires (for earrings), clasps (for bracelets and necklaces), jump rings, head pins, and bezel settings. But you might also buy manufactured stylistic components, like shapes, charms, rings, and mounted stones. A good art show wants your work to be mostly handmade — meaning that you got the raw materials and made the components yourself.

I can make ear wires, jump rings, head pins, and large (over 10 mm) bezel settings these days, but I won’t (or maybe can’t) make the kind of good, reliable clasps I want to secure my bracelets and necklaces on the wearer or the teeny-tiny bezel settings I need to set tiny stones. And although I do have the equipment and skills to polish rocks into the cabochons I use in my jewelry, that would make me a lapidary in addition to being a silversmith, and I’ve decided I don’t want to go there. (Fortunately, that isn’t expected.)

Each art show has its own standards, but the more handmade an item is, the more likely the work will get approved for a quality show.

(Of course, the actual artistic quality of the work is also considered. You can be an incredibly skilled artist but if your work looks like it was made by a kindergartener who’d been drinking espresso, you probably won’t get far. But that’s a whole other topic for discussion elsewhere.)

Unfortunately, not everyone is honest about how they make their “artisan” goods. People lie on applications. Sometimes they buy “handmade” items from overseas and try to pass it off as their own. Other times, they buy manufactured items and assemble them and pass off the results as handmade.

Assemblers are Not Artisans

The assemblers bother me a lot. Let’s take a look at this.

Here’s the Gullaberg dresser from IKEA. It won’t look like this when you buy it.

Say you go to IKEA and you buy a dresser. It comes in a flat box with instructions in an often-mocked format. You open the box and remove all the pieces, including laminated wood panels, drawer sliders, hardware, and maybe even a few primitive tools that you supplement with your own tools. You decipher the instructions and you assemble the parts into a dresser. Would you then tell someone you made that dresser? Would you bring it to an art show and try pass it off as a handmade item?

Of course not. (At least I hope not.)

So tell me this: what’s the difference between doing that and buying a bunch of manufactured jewelry components and putting them together into a piece of jewelry? Could you tell someone you made that jewelry? Can you bring it to an art show and try to pass it off as a handmade item?

Well, some people do.

The only distinction I see here is that the IKEA furniture comes with instructions and if you don’t put it together the right way, you won’t have the dresser in the picture. Or maybe any dresser or usable piece of furniture at all. If you assemble manufactured jewelry parts, you have more creative freedom. But that still doesn’t mean you made the jewelry. It means you assembled it.

Like that IKEA dresser.

Making the Parts

Step-by-Step, with PhotosA little side note here. If you follow my Mastodon account (@mlanger@mastrodon.world) and you pay attention on one of my jewelry shop days, you’ll likely see at least one thread where I discuss and illustrate the various steps for making a piece of jewelry. I do this because it interests some people and because I want people to understand the amount of work and often highly specialized tools that are required to make the jewelry I make.

Forgive me for using jewelry as an example, but that’s what I know best. So let me tell you a little bit about what goes into making the parts of a piece of jewelry.

I’ll start with something simple: an ear wire. An ear wire is the part of an earring that attaches a hanging earring to your ear. It does this by going through a piercing on your ear.

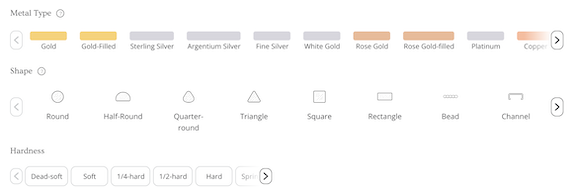

The first step is getting the raw material, which is wire. I need to know what kind of wire to get. While it’s true that I can buy stainless steel wire, which is cheap and will do the job, some folks are allergic to stainless steel — including me — so it’s an irritant for an ear piercing. There’s also silver plated, which is cheaper than sterling, sterling silver, or fine silver. Fine silver doesn’t tarnish as quickly as sterling but it’s expensive and soft so it will require extra work to harden. There’s also gold and white gold and rose gold and gold filled at different quality points. And platinum. And titanium. And copper and nickel and brass. A lot of choices! I have to know which one to buy to compromise between price and quality and help me achieve the artistic aesthetic I want.

My jewelry supplier now has this handy wire selector to help you find the wire you want. The trick is, you have to know which wire you want first.

I also need to know how thick that wire needs to be. Too thick and it will be too thick to comfortably go through an ear piercing. Too thin and it’ll bend when it’s put on or in use. And the hardness is important, too.

So far, these are all decisions. I haven’t actually made anything yet.

Yes, it’s true. My favorite jewelry making wire cutters are actually made for the electronics industry.

So I buy the wire. It’ll either arrive in a coil or on a spool depending on how thick it is. I have to cut off the length I need for the ear wire. The length depends on the style I want for the ear wire. That’s where the creative process comes in. I have to have a design for the ear wire that not only meets my artistic needs, but functions as an ear wire.

This is my go-to tool for making ear wires. I rarely use them for making bails.

With the design in mind, I cut off the length of wire I need. I then get out my forming tools — usually a bail-making pliers — and shape the wire into the ear wire shape I need. Sometimes I include decorative elements, like beads, which need to be added before the ear wire is complete.

Does the wire need to be hardened? If it’s a soft wire, it will need me to perform additional steps which could include hammering or tumbling to prevent the wire from accidentally bending in use after it has attached to make the final earring.

Now this is just an ear wire, which is one of the three simplest components I can make. (The others are head pins and jump rings.) It’s easy to make and I’ve made hundreds of them at this point. Would it be easier to buy them pre-made? Sure! In fact, I used to do just that. But then I realized that the more manufactured components I had in my jewelry, the more I looked like an assembler instead of a maker. And the more art show juries thought the same way.

These earrings have just three components each, but I use a variety of tools and techniques to make them.

And I need to point out here that the ear wire is only part of an earring. The photo here shows an example of a pair of earrings I designed and make entirely from sterling silver wire and sheet. Each earring has three components, each of which required cutting, shaping, texturing, and polishing using a wide variety of tools and techniques. I make these in batches, completing a batch of each component at a time, and can spend an entire day making just eight pairs. Figure an hour per pair on average.

Assembly is Quick

It’s not the assembly that takes all day. That takes minutes. It the manufacturing of each individual component that takes so much time. And I hand-make each component so it looks exactly the way my design — a function of my own creativity — needs it to look.

It Takes YearsMy friend Janet LeRoy is an artist who has been making a living for more than 40 years painting mostly wildlife on mostly feathers. She does a lot of art shows ranging from crappy shows not much better than glorified flea markets (mostly for convenience; long story there) to extremely high end fine art shows in Scottsdale, Jackson Hole, and beyond.

One of the questions she gets a lot is “How long did it take you to paint this?” Her response these days: “40 years.” Every single thing an artist creates is the end result of the amount of time she has been working on her art, developing her style and techniques. Keep that in mind the next time you look at original art.

So yeah: I get pissed off when I’m put into an “artisan” fair among assemblers. It took me an hour working with tools I bought using skills I developed through training and practice and using quality materials like sterling silver and onyx beads to make one pair of these earrings. So yes, I have to charge $44/pair. Meanwhile, three booths down, an assembler who bought stainless steel and chrome-plated components made in a Chinese factory spent 5 minutes putting them together with a pair of pliers can charge just $15/pair.

A buyer might not see the difference. It’s a pair of earrings! It’s silvery and shiny! Why should I buy the $44 pair when I can buy the $15 pair? They don’t care if the finish starts flaking off in a few weeks or if the ear wire makes their piercing turn red or get itchy. They’ll eventually just throw them out. $15! Who cares?

At this point, I’m starting to wonder why I should keep making the $44 pairs of earrings.

My Most Recent Unpleasant Experience

I participated in a Holiday Artisan Fair yesterday at Wenatchee’s Pybus Market and walked away feeling angry and frustrated.

Pybus was the first place I sold my jewelry, back when I only had an inventory of about 10 pieces. I was only doing wire framed cabochon pendants in those days. (Wire work is generally frowned upon by art show juries — which is why I pretty much stopped doing it — but my work isn’t the typical “wire wrapping” you see in new age crystal shops. It still sells in certain markets, but I can do a lot better.) On some weekends, there were a lot of really crappy vendors at the day tables there, selling a mixture of amateurish “granny crafts,” assembled manufactured components, and obvious buy-sell merchandise. I didn’t care much because my work really stood out in that crowd and I was able to make the sales I needed.

I stepped away from Pybus for a few reasons, not the least of which was a management change and what I saw as unfair treatment of some artists. (They definitely had their favorites and I was not among them.) Around the same time I found other venues where my work was more appreciated and sold a lot better. Instead of making a few hundred dollars in a weekend, I could bring home a few thousand. Between that and selling my work in galleries and gift shops, I no longer needed to do small shows with questionable jury practices.

Fast-forward to this autumn. After nearly two years of full-time travel, I found myself back home and ready to start selling at art shows again. But I goofed! I should have applied in spring and summer for the autumn and winter shows. I totally missed my opportunity and had no shows lined up for the holiday shopping season.

Why not try Pybus? a fellow artist who used to sell there suggested. Okay, I thought. Why not? It had been more than four years. Surely management had changed. I got on their website and applied, very happy to see how concerned they seemed to be about items being handmade. They even wanted to know where we sourced our materials. This was promising.

After some email tag with no response from the folks running the day tables there, I started thinking it was a bad idea. I told them to cancel my application.

By some miracle, they not only responded, but offered me a spot at the two upcoming Holiday Fairs. While this should have thrown up all kinds of red flags — what kind of holiday fair has openings the day before it starts? — I decided to give one day a try. They tried to get me to sign up for the second fair in December, but I told them I needed to try the first fair first.

It’s a good thing I did. They put me in a back room that few shoppers visited and surrounded me mostly with assemblers, most of whom put very little effort into their booth display. The one across from me bothered me most: all of her stuff was buy-sell with the exception of laser-cut wood items she claimed to make at home. I know that kind of work. Put a piece of wood in your cutter, push a few buttons on your computer, and go get a cup of coffee while it makes “art” you downloaded from the laser cutter company. The “Custom Hat Bar” really bugged me: take a manufactured hat, iron on a manufactured patch and you’ve got a $35 piece of assembled crap.

The person across from me threw a black sheet over her table, letting it fall where it may on the floor, and just stacked up her items for sale. This was not uncommon in the back room they stuck me in.

Meanwhile, my tables featured fitted table covers, seasonal runners, and custom displays.

Next to me was a woman selling stickers and plastic cups with decals on them. Just about everything in her booth was buy-sell with little or no effort on her part. The woman on the other side of me made artwork with real butterflies, but on seeing all the buy-sell crap around us, told me that next time she was going to bring the used books she’d bought for resale. Her idea of “handmade” was taking scrap paper, laminating it, and hanging a tassel on it to make a bookmark. When she told me all this, I wanted to suggest that she have a garage sale.

And there I was, the sucker selling handmade silver and gemstone jewelry. Or trying to. I didn’t make my first sale until 12:30 PM and, by the time I started packing up at 2 PM, I’d taken in just enough to cover my booth fee.

Lesson learned. I won’t be back.

I’m Tired of Selling with Assemblers and Buy-Sell “Artisans”

My friend Janet keeps telling me that I should just do the high end fine art shows. She says I’m ready for them, that my work is ready. I’ve always hesitated, worried that the high booth fees would make it impossible for me to turn a profit. But now I’m not so sure. I think that if I focus on taking all of my work up to the next level and leave the mass market appeal stuff behind, I have a chance of making that work for me. I have six months to maybe next winter I’ll go back on the road and start doing the good shows in Arizona and California.

The snow that’s falling outside as I type this now makes that very appealing.