The state of dog adoption in Arizona … and elsewhere?

Jack, the desert dog.

Last year, our dog Jack became ill and had to be put down. It was heartbreaking for us. Jack was only about 10 years old and he was a great dog that was really part of our lives.

Since our lifestyle was in flux, with me away from home nearly half the year and Mike commuting weekly between our Phoenix and Wickenburg homes, we decided to take a break from having the responsibility of caring for a dog. But this past summer, we began talking about finding a replacement for Jack — for filling the void his death had left in our lives.

I knew several people who were taking in foster dogs. Wickenburg had a Humane Society branch and was looking for foster homes. It seemed like a good idea — to take the responsibility of caring for a dog when it was between full-time homes.

But I soon learned that the approval process for becoming a foster home for a dog was long and drawn out, requiring multiple interviews and visits to our home. I knew they’d never approve us — one of the things they required was an enclosed backyard and although our Wickenburg yard has a low wall around it, it doesn’t have a fence. We live on 2-1/2 acres of desert and our dogs have never strayed out of our yard — let alone far from our house.

So it looked as if fostering a dog was not an option.

I also inquired about adopting a dog from the Wickenburg humane society. It shouldn’t surprise me that they had the same requirements. Apparently, they thought it was better for dogs to live with them in cages than to live with a loving family who might actually give them a life beyond a cage.

I can’t tell you how angry this made me.

Early last week, Mike met a woman who rescues Australian shepherds with visual or aural impairments. She told him about a big adoption event at the Franciscan Renewal Center on E. Lincoln Drive in Scottsdale. She said there would be lots of dogs up for adoption. So on Saturday morning, at 10 AM sharp, we were among the hundreds of people who showed up for the event.

There had to be over 200 dogs up for adoption. We looked around; it was hard to choose. We were interested in border collies and Australian shepherds but didn’t need (or even want) a full-bred dog. Jack was a mix of those two breeds, so we were familiar with them. But we just wanted a dog that was smart, could be trained to mind us, and wasn’t too big. We were especially interested in a dog that could be trained to be out in the yard by himself — with us at home, of course — and didn’t need to be on a leash all the time.

We found a group that rescues border collies and saw one we liked. I asked about the dog, who seemed very timid. Jack had also been timid, but he came out of his shell within two days.

“Oh, that’s one of the Texas dogs,” the woman told me, as if I should know all about the “Texas dogs.”

“He’s from Texas?” I asked.

“Well, haven’t you been to our Web site?”

I admitted I hadn’t.

She then proceeded to show me a printed “catalog” — what else could I call it? — of dogs available for adoption and explained how the adoption procedure worked. It was the Wickenburg humane society all over again, but with this group, we’d get multiple visits by the dog’s current foster “parent” before and after taking delivery of the dog to make sure everything was okay.

I told her I didn’t like shopping for a dog in a catalog.

She explained that even if I found one online that I liked, it might not be available. Or they might recommend a different one based on our lifestyle. In other words, the catalog was window dressing to suck you into the process — the long, drawn-out process that made you question your worthiness for owning a dog — before you’d be permitted to give the dog a home.

At least those dogs had foster families. As far as I was concerned, they’d be better off staying where they were.

We inquired at a few booths that had dogs that interested us and got the same bullshit routine.

Let me set something straight before you all jump on me. I’m not so naive to think that all dogs go to great homes. I know that some people are abusive or adopt for reasons that might not be in the best interest of the dog. I know that not everyone takes as good care of their animals as we do. I know that many dogs spend most of their time in outdoor kennels or, worse yet, crates. Some are abused. Some are neglected. Some have really crappy lives.

But I also know that a dog that lives with us has a very good life. While we don’t permit a dog to sleep in bed with us — or even sit on the furniture — and we don’t allow anyone to feed a dog from the table during meals, we do treat our dog like a member of the family. He lives indoors with us and sleeps in our bedroom on his own bed. He comes with us anywhere we can take him. He’s well-fed, gets all his shots, and gets professional medical attention promptly if he needs it. We play with our dog, pet him for no reason other than to show how much we love him, and teach him tricks. Our dogs have always been well-behaved and devoted to us. It’s a mutually beneficial relationship — the way we think a person/dog relationship should be. Best of all, because I work from home, our dog is seldom left alone for more than a few hours each week.

So I know damn well that I can give the right dog an excellent life — far better than he would have living in a cage at the Humane Society or maybe even with a foster family.

I’m not interested in trying to prove it to a bunch of strangers who would be judging me by the type of fence I have in my backyard.

Fortunately, we did find a dog we liked in the booth of an adoption organization. In fact, we found three.

I knew this organization was different from the others — they’d put low fencing around the entire booth and most of the dogs ran lose inside it. (Most of the other booths had their dogs in cage-like crates or on leashes held by foster families.) They were all mutts, all healthy looking, and all getting along fine together. We’d stopped there on the way into the event — they were right near the entrance — and Mike had liked one of the dogs. That dog had been adopted during the 40 minutes or so since our first visit. No bullshit there; this organization wanted to find homes for its dogs immediately.

When I showed interest in one of the dogs, the woman in charge, Carrie, immediately offered to let me take it for a walk. Unsupervised, if you can imagine that.

It was a small black dog with short hair. She was about a year old; the woman still had its mother, which was part Australian shepherd. The dog didn’t want to leave the pen containing her friends, but I was encouraged to just tug her out on the leash. We took a short walk; the dog was very skittish. But when I knelt down to reassure her, she was fine. I could see that with a little work, she’d be a good dog.

Mike, in the meantime, was looking at another dog who was larger and more self-assured. He said the dog was alert and following his every move. He was also one of the few dogs there in a cage-like crate — I think that should have given us a clue about his personality. Once out on a leash, he was pulling Mike everywhere, sniffing everything, trying to get to know every other dog. He was not controllable — at least not yet. I walked him for a while and soon got tired of the pulling. That dog would need a lot of work to get under control. Were we willing to put the time and effort into doing it right? I didn’t think I was.

This is Charlie in the truck on the way home from Phoenix.

We went back just as a helper brought back a black border collie that had just been to the dog wash. He looked terrible — wet yet still kind of matted — but reminded me a lot of Jack. We took him for a walk. Although he didn’t want to go with us at first, we didn’t have much trouble pulling him away. He was more confident than the little dog I’d walked, but less outgoing than the larger dog Mike had walked. He felt right.

His name was Charlie.

Charlie had been picked up by Animal Control — the same folks we used to call “the dogcatcher” when I was a kid — in Show Low, AZ a week or two before. He had a collar but no tags. No one had claimed him. Carrie’s organization works with Animal Control in Show Low and had picked up Charlie and brought him down to Phoenix. He’s about a year old and Carrie claimed he might be full-bred border collie. (I tend to doubt that, but don’t really care. I wanted a dog, not a label.) He’d been to the vet to be neutered and get his rabies shots just the week before.

He was a stray dog without a home. Just like Jack had been.

We decided he was a good match for us.

We filled out some paperwork and some money changed hands. Carrie’s helper helped Mike cut off Charlie’s old collar — the buckle was broken — and put on a new one. We put on a leash and left. Mission accomplished — same day — no interviews, no home inspections, no trial periods.

On the way out, we stopped to ring a bell the Franciscans had set up to signal an adoption. Peopled nearby clapped and cheered and congratulated us. The Phoenix Animal Care Coalition (PACC), which had sponsored the event, gave us a bag of goodies that included sample dog food, dog shampoo, a tennis ball, and PetSmart coupons.

Back at the car, I spread some throw rugs on the back seat. It didn’t take much coaxing to get Charlie to jump in. We rolled his windows down halfway, just in case he was the kind of dog who like to stick his head out. (He wasn’t; at least not then.) Then we drove him to the PetSmart near our condo and brought him inside with us. We bought him a new bed, some chew sticks, a dog dish, a water bowl, dog food, dog cookies, and a toy.

Back at the condo, we let him walk around to check the place out while we loaded up the truck. He was very interested in Alex the Bird. We put his new bed in the back seat of the truck beside Alex’s lucite box and coaxed him up on top of it. Then we made the long drive to Wickenburg, making two short stops along the way. He was very well behaved and snoozed for most of the drive.

At home, we fed him and made sure he had water before doing the odd jobs we needed to do around the house. We walked him around outside the house, both on and off leash. He stayed close by and showed no desire to run off. He chased a lizard under a woodpile and, when I called him, he came right to me.

Mike brushed him, removing a shopping bag full of old hair. (Better in the bag than on my carpet!) He looked a lot smaller — and thinner — with the extra hair gone.

We discovered that he didn’t know how to climb stairs, but Mike fixed that by giving him a few gentle tugs on the leash as he started up the stairs; once he got past the first four steps, he was fine. (No trouble coming down later, either.) When I sat on the sofa, he jumped up next to me and I told him to get down. We went though this three times before he understood and lay down on his bed, which we’d brought upstairs for him.

Later, after it had cooled down, we took him to the dog park. I’d been there once before, with Jack. Jack didn’t like playing with other dogs. Charlie does. We stayed for about and hour and chatted with the other dog owners. Most of them were pretty amazed by how well Charlie got along with the other dogs and how he already knew us, after less than six hours with us.

Last night, he slept on his bed or on the tile floor outside our bedroom door. He was quiet. He didn’t have any accidents in the house.

This morning, he came downstairs for breakfast with me. I fed him and he gobbled it down. Later, after breakfast, we fed him some more. We need to fatten him up a bit; he really is too thin. I’ll take him to our local vet on Monday, if I can get an appointment, and weigh him so we know how much he should be fed. I’ll also ask whether puppy food would be better than adult food for him until he’s at the right weight.

Today, we left the back door open wide enough for him to go out on his own. He stayed close by, except when he was chasing rabbits. He got into some cactus but managed to pull most of the bigger spines out on his own; we pulled the rest out while he waited patiently.

Later today, we’ll take him down to Box Canyon, where the Hassayampa River flows through a narrow slot canyon. We’ll see what he thinks about riding in the back of a Jeep with the side and back windows off and whether he likes water.

This week, we’ll buy him one of those soft-sided Frisbee-like discs to see if we can teach him to catch.

And I’m already looking into sheep herding training for him, just to see if he’s got what it takes to be a real ranch dog.

For the next ten to 15 (or longer?) years, Charlie will be our not-on-the-furniture, no-begging-at-the-table, no-jumping-up-on-people-univited kid.

He’s a lucky dog — even if most dog adoption agencies don’t think we’re good enough to have a dog — and we know we’re lucky to have him.

We’d been talking to people about dogs and learning about different breeds well-suited for ranches. I’d decided that something like a border collie or Australian shepherd would be a good breed. So when the newspaper mentioned a border collie/Australian shepherd mix up for adoption, we decided to take a look.

We’d been talking to people about dogs and learning about different breeds well-suited for ranches. I’d decided that something like a border collie or Australian shepherd would be a good breed. So when the newspaper mentioned a border collie/Australian shepherd mix up for adoption, we decided to take a look. He bonded to me — probably because he’d been sitting on my lap on that car ride. This was not ideal. I’d planned to get a parrot in a month or so and Jack was supposed to be mostly my husband’s dog. So for the first few days, I began ignoring him and Mike started lavishing him with attention. After a few days of that, he was Mike’s dog, although he responded to me equally well. But when we were together, it was always Mike that he went to first. That was fine with me.

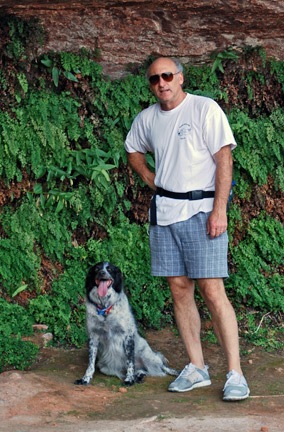

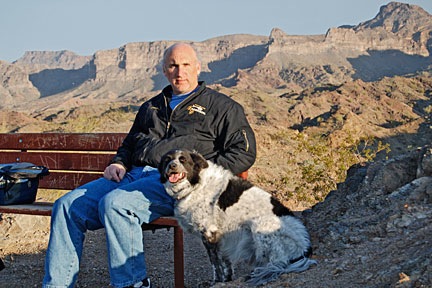

He bonded to me — probably because he’d been sitting on my lap on that car ride. This was not ideal. I’d planned to get a parrot in a month or so and Jack was supposed to be mostly my husband’s dog. So for the first few days, I began ignoring him and Mike started lavishing him with attention. After a few days of that, he was Mike’s dog, although he responded to me equally well. But when we were together, it was always Mike that he went to first. That was fine with me. Jack sitting on the edge of the back patio, watching the road that leads down to our house, racing around to the front when Mike’s car or truck rolled down.

Jack sitting on the edge of the back patio, watching the road that leads down to our house, racing around to the front when Mike’s car or truck rolled down. Jack running around on our 40 acres in northern Arizona, chasing rabbits, crawling under the shed, looking for mice and rats.

Jack running around on our 40 acres in northern Arizona, chasing rabbits, crawling under the shed, looking for mice and rats. Jack hiking with us up Vulture Peak, through the Hassayampa River bed, at Granite Mountain,

Jack hiking with us up Vulture Peak, through the Hassayampa River bed, at Granite Mountain,  Jack riding in the back of the pickup, his head out in the slipstream as we drove around town. (He only fell out of the pickup that one time, although he did fall out of my Jeep twice.)

Jack riding in the back of the pickup, his head out in the slipstream as we drove around town. (He only fell out of the pickup that one time, although he did fall out of my Jeep twice.)