The pilot really does know best.

The other day, I had a very unusual aerial photography job. I was hired to take two videographers on an air-to-air photo shoot of the world’s largest paper airplane.

There were a few things about this gig that bugged me and, frankly, it all had to do with the primary videographer on the shoot. He did things that severely limited our ability to get the shots he needed and rendered some of my equipment non-functional after the flight.

I’d like to discuss this in a bit of detail in an effort to help other videographers understand how to make the most of an aerial video shoot.

Bad Seating Position

This was an air-to-air photo shoot requiring me to fly in formation with another helicopter that was towing an 800-pound, 45-foot “paper” airplane. (I put paper in quotes because there was some cardboard and tape and metal spars for stabilization, but it was mostly paper.) When the other helicopter dropped the airplane, I’d have to chase the airplane down to the ground. We had no idea how fast the airplane would fly or whether it would fly smoothly or erratically. And, of course, the other helicopter would be dangling a 150-foot long line, so it was vital that I didn’t fly right beneath it after the drop.

The other pilot and I agreed that I’d form up on him. What that means is that he basically ignores me and I have sole responsibility for maintaining a safe distance from him. He’s the “lead,” I’m the “wing.”

In order to maintain a safe distance, I have to be able to see the other aircraft at all times. Seems pretty simple, huh? Can’t maintain a safe distance from something you can’t see.

And this is where the problem arose. In order for me to see the other aircraft, I need a direct line of sight to it. I can’t see through a videographer’s body.

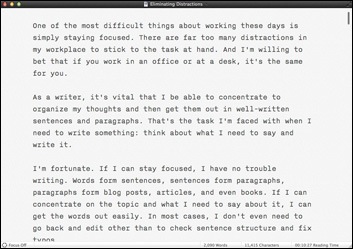

I asked the videographer to sit in the back, behind me. This would give both of us the same view. This is how I prefer to work. It enables me to keep the helicopter in position for the shot. I’ve done this on numerous photo shoots with fast-moving targets. It works.

This is a frame-grab from one of my GoPros. Ideally, I should have had only one videographer on board and he should have been sitting behind me.

But the videographer refused to even consider sitting in the back seat. He had to sit in the front. This forced me, in the right seat, to fly with the other aircraft on my left. The videographer’s body obstructed my view to the left toward the other aircraft.

Although I was able to see the other aircraft most of the time, there were two or three instances when I could not see it. To stay safe until I could regain a visual on it, I banked away from where I thought it might be.

The videographer was not happy about this. “Get closer,” he’d say. And I’d reply, “I can’t get closer to something I can’t see.”

On a go-forward basis, I will not allow a photographer or videographer to block my view on any air-to-air photo shoot. If he can’t sit behind me so we can both see the other aircraft, I won’t do the flight. Period.

Poor Choice of Equipment

Two years ago, I spent over $10,000 on a Moitek gyro-stabilized video camera mount. This system uses three Kenyon KS-8 gyros to remove virtually all vibration from a camera while bearing all the weight of the camera equipment and giving the videographer a wide range of motion left, right, up, and down. No, it’s not as flexible as a hand-held camera, but as long as the videographer can keep the subject in the frame, he’ll get smooth video of it.

In an effort to recoup the cost of this system — and compensate me for the 30 minutes of setup and 30 minutes of tear-down time required for use — I charge $500 per day.

I offered this to the client though the booking company they were working with. They declined. I assumed they preferred to hand-hold the camera.

RED and redder.

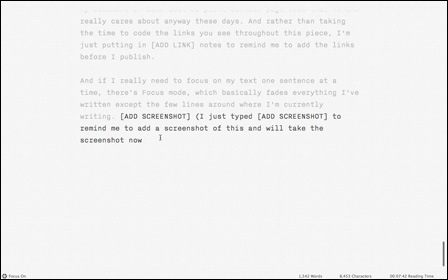

When I arrived for the shoot, I discovered that the video guy had rented a Tyler Mini Gyro. This device has three smaller gyros mounted on a short monopod. The camera is mounted on top. The videographer usually places the monopod between his legs on the seat or on his lap while shooting. This stabilizes the video but limits motion in that the monopod base needs to be repositioned to make a significant vertical change of view. Without moving the base, the videographer would need to lean out into the slipstream to look down or lean back into the cockpit to look up. This isn’t always possible.

Apparently, the videographer was relying on me to keep in perfect formation with the other aircraft to prevent his need to move the camera. This was not possible, as discussed above. So when the paper airplane was released and it began its steep descent, he was unable to stay locked onto it with his camera.

I think using my mount or hand-holding the camera — possibly with a simpler gyro mount such a Micro-Gyro Mount offered by Blue Sky Aerials would have really benefited him. And I find it odd that although his equipment included a very costly RED camera, he had to rely on a rented gyro stabilizer.

Tampering with My Equipment

As discussed in numerous places throughout this blog, I’m a big fan of GoPro cameras and have three of my own that I sometimes use in flight. The folks from GoPro were at this event and they rigged up a bunch of their cameras all over the paper airplane and lift helicopter. They were thrilled that I already had good mounting solutions and loaned me a Hero 2 for one of my mount positions. So my helicopter had three GoPros, one of which was not mine, each of which had one of my 16GB cards in it. My arrangement with the GoPro guys was that after the flight, they’d pull video off each card and give the card back to me for my own personal (but limited) use.

Note that I mounted all the cameras with the GoPro guys. The video guy did not participate in this at all.

We did the flight and landed out in the desert near where the paper airplane had crashed. They did some video of the recovery on the ground. When we got back to my helicopter, I noticed that one of the GoPro mounts was missing its camera. I assumed it had fallen off and was very surprised because I know from experience how solid that mount is. That’s when the videographer told me he’d already removed them. Sure enough, all three mounts had been tampered with and all three cameras were gone.

Back at base, I went to the GoPro guys to find my cameras and the missing pieces of my mounts. They stuck to their word and I got everything back — except a piece from each of two mounts: a vibration isolator and a thumbscrew. Without these two pieces, two of the mounts are non-functional.

I don’t know who has them: the videographer or the GoPro guys. I suspect it’s the videographer. He likely put them in his pocket when he disassembled the mounts and forgot to give them back. (He also forgot to return a harness I provided for the shoot. That’s being shipped back to me this week.)

It is a Federal offense to tamper with equipment on an aircraft. Obviously, I’m not going to call the FAA to give this guy grief. But I will make sure it doesn’t happen again.

The Pilot Really Does Know Best

When you hire an experienced pilot for an aerial photo or video shoot, you need to fully communicate the needs of the mission before the flight and listen to the pilot’s advice. You need to work with your pilot to make a team to get the job done.

I know for a fact that I could have flown in perfect formation with the other aircraft if I could have seen it out my own window. I have done this before — not only with aircraft but with cars and trucks on the ground on tracks and on desert race courses, and with boats on lakes and rivers. A pilot cannot be expected to fly in formation with something he can’t see.

I know this videographer was unhappy with the results he got. But who is really to blame? I don’t think it’s me.