Education is the best way to deal with safety concerns — especially if you’re a pilot.

I recently took part in a forum discussion that revolved around safety issues. The person who started the discussion, a helicopter pilot training to be a CFI, was concerned about the possibility of flight schools emphasizing the fun part of flying without adequately addressing the dangers. It wasn’t a failure to teach emergency procedures that bothered him. It was the attitude of flight schools and CFIs. He worried that flight schools, in an attempt to keep enrollment high, were failing to make students understand just how dangerous flying helicopters can be.

While I’ll agree that flying helicopters is dangerous, I also agree that driving a car or or crossing the street is dangerous. In fact, you stand a far more likely chance of being injured or killed in a motor vehicle than in an aircraft. The pilot who started this discussion knows this, but he still wonders whether flight schools should be making student pilots more cognizant of the dangers, especially early on in training.

I understood his point of view, but I really don’t know firsthand how much his flight school is downplaying the dangers. The general feeling I came away from after reading his comments was that he had a fear of flying. (This turned out not to be the case.) While it’s always good for a pilot to be afraid of what could happen, there comes a point where the level of fear becomes unhealthy. Yes, it’s true that pilots need to be mentally prepared to react to an emergency within seconds. But no, we don’t need to spend every moment of every flight actively thinking about all the emergencies that could ruin our day — or end our life.

Experiences Teach

I flew with a 300-hour pilot a few years ago. He’d gone through training and was a CFI looking for a job. (I have flown with quite a few CFIs looking for jobs, but that’s another story.) We were on a cross-country, time-building flight in my R44. I would eventually fly a total of 20 hours with him.

Early on in our first flight, I learned that his CFI, who was the flight school’s Chief Flight Instructor, had been killed in a rather disturbing fiery crash. Although she had over 2,000 hours of flight time, she had only 24 hours in the helicopter make and model. On that fateful day, the NTSB concluded that the accident was caused by:

The pilot’s improper planning/decision in attempting a downwind takeoff under high density altitude conditions that resulted in a loss of control and impact with terrain. Contributing to the accident were the helicopter’s gross weight in excess of the maximum hover out of ground effect limit, a high density altitude, and the gusty tailwind.

(I don’t really want to discuss this accident here; I think deserves a discussion of its own elsewhere in this blog and hope to address it in the months to come.)

It soon became apparent to me that the pilot was unusually fearful of flying in the mountains. Our route required us to fly west from Wickenburg, AZ to the California coast near San Luis Obispo. He started fretting about the mountains ahead of us while we were still in the flat deserts of Southern California. The mountains he was worried about showed elevations of 5,000 to 8,000 feet on the chart; we’d be flying over a road that ran in a relatively straight and wide canyon. That part of the flight turned out to be uneventful and he seemed genuinely relieved when it was finished.

It soon became apparent to me that the pilot was unusually fearful of flying in the mountains. Our route required us to fly west from Wickenburg, AZ to the California coast near San Luis Obispo. He started fretting about the mountains ahead of us while we were still in the flat deserts of Southern California. The mountains he was worried about showed elevations of 5,000 to 8,000 feet on the chart; we’d be flying over a road that ran in a relatively straight and wide canyon. That part of the flight turned out to be uneventful and he seemed genuinely relieved when it was finished.

Oddly, later in the flight, when the Monterey tower instructed us to cut across Monterey Bay at an altitude of only 700 feet, I was pretty freaked out. Here we were, in a single-engine helicopter flying far from gliding distance of land, without pop-out floats or personal floatation devices. My companion, on the other hand, was perfectly at ease. In fact, I think he thought me cowardly when I asked Monterey tower for clearance to fly closer to shore.

Oddly, later in the flight, when the Monterey tower instructed us to cut across Monterey Bay at an altitude of only 700 feet, I was pretty freaked out. Here we were, in a single-engine helicopter flying far from gliding distance of land, without pop-out floats or personal floatation devices. My companion, on the other hand, was perfectly at ease. In fact, I think he thought me cowardly when I asked Monterey tower for clearance to fly closer to shore.

This is a great example of how experience teaches. My companion was a “sea level pilot,” who did all of his training — and flying — in the watery areas around Seattle. He was comfortable with water and low-lying lands, but he was fearful of the conditions that had taken the life of someone he knew very well. I was a desert pilot with most of my experience flying over dry land, much it in high density altitude situations, including more than 350 hours flying tours over the Grand Canyon at 7500 feet or higher. I was comfortable flying over most kinds of terrain at just about any altitude but very fearful of flying over water.

(Nowadays, I wear a PFD when doing any extended flying over water and require my passengers to do the same.)

Learn from Other People’s Mistakes

Back in the forum, I began wondering if the pilot who had started the thread was concerned because he’d lost someone close to him in a crash — much like my cross-country companion had. (That turned out not to be the case.) I said:

If a person thinks too much about the danger of ANYTHING, they won’t be comfortable doing it. I admit that I don’t concern myself with it. I do everything I can to fly safely and maintain a safe aircraft. I’m confident in my abilities and never push the envelope of comfort more than I absolutely need to. I don’t fly around thinking that at any moment, something bad could happen. If I did, I’d hate flying and I’d likely be a horrible pilot.

Later, in the same post, I said:

You might also consider reading NTSB reports for helicopter accidents. What you’ll find is that most accidents are caused by pilot errors. REALLY. Reading those reports will help you learn what mistakes others have made so you’ll avoid them in the future.

He saw these two comments as conflicting and replied that I couldn’t really say that I wasn’t concerned with danger if I was reading accident reports.

My response was:

You need to understand that it’s BECAUSE I read the NTSB reports that I’m NOT overly concerned with the dangers of flying. The NTSB reports educate me about what can happen when you do something dumb: fly too heavy for your type of operation, perform maneuvers beyond the capabilities of your aircraft, fly into clouds or wires, etc. Each time I read a report and understand the chain of events that caused the accident, I file that info into my head and know to avoid the same situation.

I went on to say a lot more about what I’ve learned from NTSB reports. I read them for helicopter accidents at least once a month. Another pilot in the forum said he does the same thing — in fact, he even has a browser bookmark that’ll pull up the reports by month! I cannot say enough about the usefulness of these accident reports for training and awareness.

Unanswered Questions Can Fuel Fear

As I look back now on the flights I took with that mountain-fearful CFI — with the forum discussion in mind — I’m wondering whether the flight school had properly debriefed its students after the loss of the Chief Flight Instructor.

What had the flight school told him and the other pilots? Had they told him what caused the crash? I know that back then, before the NTSB report was issued, the flight school was in denial about the aircraft being overweight for the operation. Had they told their students anything at all? Were my companion and the other pilots and student pilots at that flight school left to wonder how such a great, experienced pilot could have been involved in a crash in the mountains?

Were his unanswered questions fueling his fear?

Another thing I suggested in the forum is that flight schools might want to conduct monthly seminars that students are required to attend as part of ground school training. Get all the students and CFIs into a classroom or meeting room with a few knowledgable, experienced pilots at the front of the room. Pick 3 to 5 recent helicopter accidents for which the cause is known. Talk them out. Explain what went wrong and what could have prevented the accident. Don’t point fingers; present facts.

Why don’t flight schools do this? Could it be because of what this forum pilot originally said: flight schools don’t want to scare off students by discussing dangers? If so, they’re doing their students — and the rest of the aviation community — a serious disservice.

Education and Experience are the Answers

Nowadays, if you want a job as a pilot carrying passengers for hire, you’ll need at least 1,000 hours of experience as a pilot in command. (Yes, I know some companies will take less, but those are few and far between.) There’s a reason for this: they want pilots who have experience flying. Experience leads to skills, knowledge, and confidence.

Some people think 1,000 hours is an arbitrary number and frankly, I have to agree. My first 500 hours were very different from the average CFI’s first 500 hours — in some respects, my experiences are “better,” while in other respects, a CFI’s experiences are “better.” But I also can’t see any other easy way to gauge a job applicant’s level of experience.

But it isn’t just experience that makes a pilot a good pilot. It’s also knowledge and attitude. Both of these things could be the end product of a flight school’s training program.

Many flight schools seem satisfied getting students and putting them through a “program” with just enough skills and knowledge to pass a check ride. Many students, who don’t know any better, are more interested in the cheapest way to get their ratings than the quality of the training.

I believe that with better quality training and better quality experience, less hours of experience should be necessary to have and prove good piloting skills. I also believe that pilots with better quality training and experience will have a better, safer attitude toward their responsibilities as a pilot.

It’s not a matter of teaching new pilots to be fearful of what could happen by stressing the dangers of flying. It’s a matter of educating about dangers — and how to avoid them.

What do you think?

A few weeks ago, it came to my attention that this blog was the primary source of information about cherry drying by helicopter. Every day, pilots who wanted to learn more about cherry drying were stopping in to read up.

A few weeks ago, it came to my attention that this blog was the primary source of information about cherry drying by helicopter. Every day, pilots who wanted to learn more about cherry drying were stopping in to read up. My friend met me at the airport. He’s a helicopter pilot too and he’s also in Washington to dry cherries. His helicopter is parked at an orchard. There were two other R44s parked in a field at the airport and I parked with them. But I didn’t bother shutting down. I invited my friend to join me for a flight further up the river to Brewster, where another friend of mine’s old Sikorsky S55T (and that T stands for “turbine”) is recovering from a mishap last season. We flew up the river, pointing out all the orchards we’d dried in the past along the way.

My friend met me at the airport. He’s a helicopter pilot too and he’s also in Washington to dry cherries. His helicopter is parked at an orchard. There were two other R44s parked in a field at the airport and I parked with them. But I didn’t bother shutting down. I invited my friend to join me for a flight further up the river to Brewster, where another friend of mine’s old Sikorsky S55T (and that T stands for “turbine”) is recovering from a mishap last season. We flew up the river, pointing out all the orchards we’d dried in the past along the way.

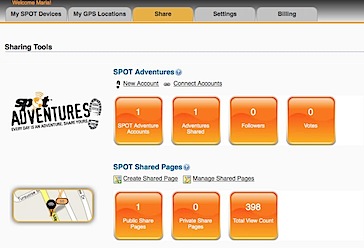

Click the Share tab near the top of the page.

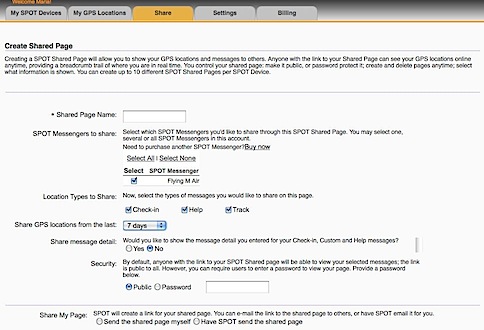

Click the Share tab near the top of the page. Set the options in the Create Shared Page window that appears. Be sure to enter a Shared Page Name and select your SPOT device. Under Security, you can specify whether the page is Public or requires a Password to access. Personally, I recommend keeping it Public. You can always limit who you give the URL to. It would be terrible if someone needed to access the information and couldn’t remember the password.

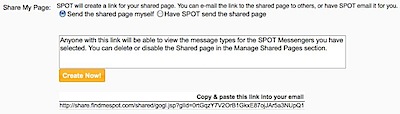

Set the options in the Create Shared Page window that appears. Be sure to enter a Shared Page Name and select your SPOT device. Under Security, you can specify whether the page is Public or requires a Password to access. Personally, I recommend keeping it Public. You can always limit who you give the URL to. It would be terrible if someone needed to access the information and couldn’t remember the password. At the bottom of the page, a very long URL should appear. Triple-click it to select it and chose Edit > Copy (or press Command-C (Mac) or Control-C (Win)) to copy it to the clipboard. We’ll use it in a moment to test the link and create a short URL.

At the bottom of the page, a very long URL should appear. Triple-click it to select it and chose Edit > Copy (or press Command-C (Mac) or Control-C (Win)) to copy it to the clipboard. We’ll use it in a moment to test the link and create a short URL. If, for some reason, you didn’t get the URL or you need to access it again in the future, click the Shared tab (shown above) and then click the Manage Shared Pages link under SPOT Shared pages. You can click the name of the shared page to display it. You can then copy the link for that page from the Web browser’s address bar.

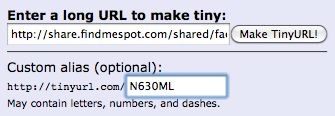

If, for some reason, you didn’t get the URL or you need to access it again in the future, click the Shared tab (shown above) and then click the Manage Shared Pages link under SPOT Shared pages. You can click the name of the shared page to display it. You can then copy the link for that page from the Web browser’s address bar. Paste the URL for your shared page in the top text box.

Paste the URL for your shared page in the top text box. Click Make TinyURL!

Click Make TinyURL!