Why a control tower clearance is something to be taken with a grain of salt.

When you fly in airspace controlled by a control tower, you’d think that a controller clearance would be a green light to do what you were cleared to do. Unfortunately, controllers can give a green light to other traffic that might just conflict with you. I’ve had this happen four times in the past six months.

The first three times were at Grand Canyon airport (GCN) while I worked for Papillon. Papillon has a heliport with eleven helipads. The area behind the pads, which is known as “the meadow,” is our departure and landing point. To depart, we back off a pad, maneuver to the meadow, contact the tower, get a clearance, and depart using either north or south traffic, whichever is on the ATIS. On average, Papillon operates about nine helicopters during the busy summer season.

There are two other helicopter operators at the canyon. Both have considerably smaller heliports south of Papillon’s. Grand Canyon Helicopters operates three helicopters from its location. AirStar operates four helicopters at its location. So you have about 16 helicopters operating on an average busy day, all out of the same general area of the airport: the northeast corner.

Now look at the picture here. In the first two close call incidents, I was the red line, which got clearance to depart to the southeast. In one incident, the blue line (Grand Canyon Helicopters) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In another incident, the green line (AirStar) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In both cases, I had to alert the departing pilots — on the tower frequency — that I was in their departure path. In one case, I actually began evasive maneuvers when the pilot didn’t appear to hear me. Mind you, the tower had given all of us clearance so we were all “cleared” to depart. Scary, no?

Now look at the picture here. In the first two close call incidents, I was the red line, which got clearance to depart to the southeast. In one incident, the blue line (Grand Canyon Helicopters) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In another incident, the green line (AirStar) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In both cases, I had to alert the departing pilots — on the tower frequency — that I was in their departure path. In one case, I actually began evasive maneuvers when the pilot didn’t appear to hear me. Mind you, the tower had given all of us clearance so we were all “cleared” to depart. Scary, no?

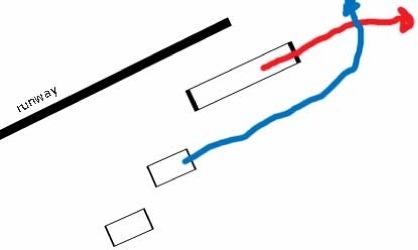

Let’s look at another close call. In the picture to the right, I was the red line with a clearance to depart to the northeast. The blue line had just gotten a clearance to depart to the northwest. Because he took off before me, we were on a collision course. But I’d been listening and I heard him get the clearance. So when I took off, I kept an eye out for him and made sure I passed behind him.

Let’s look at another close call. In the picture to the right, I was the red line with a clearance to depart to the northeast. The blue line had just gotten a clearance to depart to the northwest. Because he took off before me, we were on a collision course. But I’d been listening and I heard him get the clearance. So when I took off, I kept an eye out for him and made sure I passed behind him.

I’m not trying to get anyone in trouble here. Believe me, in the first two incidents I made quite a bit of noise on the radio to the tower for handing out two conflicting clearances. Unfortunately, they did it to a few other pilots before one of them got on the phone and made some noise. Near the end of the season, the tower was very good about alerting us to possible conflicting helicopter traffic, even when the possibility of a conflict was minor.

My most recent controlled close call incident was two days ago. I’d gone down to Chandler to meet a friend for lunch. I landed at the Quantum ramp at Chandler Airport (CHD). We had lunch and returned at close to 1 PM — just when Quantum’s training ships were returning. I asked for and got clearance to hover-taxi to the heliport’s landing pad. I then asked for and got an Alpha departure clearance. This requires me to take off from the helipad and follow a canal that runs beside the airport (and helipad) to the north (the red line). When I got my clearance, the tower alerted me to an inbound helicopter that was crossing over the field. I did not hear that helicopter get a landing clearance, but he may have gotten it from Chandler’s south frequency, which I was not monitoring (because I could not). I took off along the canal just as the other helicopter (the purple line) turned left to follow the canal in. We were definitely on a head-on collision course. I saw this unfolding and diverted to the west, just as the tower said something silly like, “Use caution for landing helicopter.” Duh. I told the tower I was moving out of the way to the west. There was no problem. But I wonder what that student pilot thought. Or what Neil, owner of the company, thought as he hovered near the landing pads in an R44, watching us converge.

My most recent controlled close call incident was two days ago. I’d gone down to Chandler to meet a friend for lunch. I landed at the Quantum ramp at Chandler Airport (CHD). We had lunch and returned at close to 1 PM — just when Quantum’s training ships were returning. I asked for and got clearance to hover-taxi to the heliport’s landing pad. I then asked for and got an Alpha departure clearance. This requires me to take off from the helipad and follow a canal that runs beside the airport (and helipad) to the north (the red line). When I got my clearance, the tower alerted me to an inbound helicopter that was crossing over the field. I did not hear that helicopter get a landing clearance, but he may have gotten it from Chandler’s south frequency, which I was not monitoring (because I could not). I took off along the canal just as the other helicopter (the purple line) turned left to follow the canal in. We were definitely on a head-on collision course. I saw this unfolding and diverted to the west, just as the tower said something silly like, “Use caution for landing helicopter.” Duh. I told the tower I was moving out of the way to the west. There was no problem. But I wonder what that student pilot thought. Or what Neil, owner of the company, thought as he hovered near the landing pads in an R44, watching us converge.

The point of all this is, when you get a tower clearance, that doesn’t mean you can stop scanning for traffic. That should never stop. Controllers are human and they can make mistakes. And frankly, I believe that they are so concerned with airplane traffic that they tend to get a bit complacent when it comes to dealing with helicopters.

Consider Grand Canyon tower. With 16 helicopters operating in and out of the airport all day long, all on predefined arrival and departure routes, things get pretty routine. The pilots all know what they’re doing. The tower knows the pilots will do the same thing each time they get a clearance. There’s no chance of misunderstanding an instruction because the instructions are part of pilot training and an average pilot will fly ten or more flights per day when working. It’s like a well-oiled machine. The problem arises when the controller gives clearances for departure paths that will cross in flight. Although the controller should not do this (my opinion), it happens. It’s then up to the pilot to listen for all clearances and spot other aircraft that might conflict.

Chandler tower deals with helicopter traffic from Quantum and Rotorway. Again, these pilots know the arrival and departure paths. And, in most cases, there’s a CFI on board, someone who has been flying out of Chandler for at least a year. The tower probably hands out clearances without thinking too much about them. After all, the helicopters will remain clear of the fixed wing traffic, and that’s their primary concern.

As a helicopter pilot, I’ve come to understand all this. And although I wish controllers would be a little more cautious when issuing clearances, I’m not too concerned about me hitting someone else. I use my eyes and my ears to monitor my surroundings. I can slow down — or even stop in midair! — to avoid a collision. I can also descend very rapidly and, if I’m not too heavy, climb pretty rapidly, too. I can also make very sharp turns. In short, my ability to avoid a collision is much better than the average fixed wing pilot’s.

What does worry me, however, is the possibility of a less experienced or less familiar pilot acting on a clearance that puts him on a collision course with me in a position where I can’t see him. Suppose I’d taken off on an Alpha departure at Chandler and had gained some altitude. Suppose the other helicopter was not in front of me, but coming up on my right side, slightly behind me with a solo student pilot at the controls. That pilot could have still been tuned into the south tower frequency. So even if the north controller had issued his “use caution” warning, the student pilot would not have heard him. I wouldn’t have seen him. He could have hit me. Scary thought.

Of course, you can play what if all day long. If you come up with enough scary scenarios, you’ll park your aircraft in the hangar and leave it there. That’s not me. I’ll keep flying.

And keep looking.

This first shot is a group shot one morning before preflight. One of the pilots (Bubbles, I think), had brought a camera and asked if we’d all go down and pose in front of a ship. It turns out that five or more of us had cameras with us so the loader who took the picture was pretty busy. Back row, from left to right: Don (“Gorgeous Don”), Greg (“Clogger”), Walter (“Wheezer”), Scott, me, Tom. Front Row, from left to right: Tyler (“Daisy”), Ann, Chris (“Bubbles”), Ron, Eduardo, Vince. This isn’t everyone, of course. Just the folks that were around that morning. If anyone has a shot of a different crew from this year, please e-mail it to me.

This first shot is a group shot one morning before preflight. One of the pilots (Bubbles, I think), had brought a camera and asked if we’d all go down and pose in front of a ship. It turns out that five or more of us had cameras with us so the loader who took the picture was pretty busy. Back row, from left to right: Don (“Gorgeous Don”), Greg (“Clogger”), Walter (“Wheezer”), Scott, me, Tom. Front Row, from left to right: Tyler (“Daisy”), Ann, Chris (“Bubbles”), Ron, Eduardo, Vince. This isn’t everyone, of course. Just the folks that were around that morning. If anyone has a shot of a different crew from this year, please e-mail it to me. This second shot is the instrument panel on a Bell LongRanger. This happens to be Copter 30, but they all looked pretty much alike. I took this picture while I was idling on the ground at the heliport, waiting for passengers. The instruments from top to bottom, left to right are: Oil pressure and temperature, Transmission Oil pressure and temperature, Fuel level, DC Load and Fuel pressure; next row down: Torque, TOT, N1, time (clock); next row down: Airspeed Indicator, N2/Rotor RPM; next row down: Attitude Indicator, Directional Gyro (incorrectly set but I always used the compass, which is not shown in this photo), ball (for trim indication); last row down: altimeter, vertical speed indicator, another ball (for trim indication; I didn’t realize there were two on this ship until just now).

This second shot is the instrument panel on a Bell LongRanger. This happens to be Copter 30, but they all looked pretty much alike. I took this picture while I was idling on the ground at the heliport, waiting for passengers. The instruments from top to bottom, left to right are: Oil pressure and temperature, Transmission Oil pressure and temperature, Fuel level, DC Load and Fuel pressure; next row down: Torque, TOT, N1, time (clock); next row down: Airspeed Indicator, N2/Rotor RPM; next row down: Attitude Indicator, Directional Gyro (incorrectly set but I always used the compass, which is not shown in this photo), ball (for trim indication); last row down: altimeter, vertical speed indicator, another ball (for trim indication; I didn’t realize there were two on this ship until just now).

Now look at the picture here. In the first two close call incidents, I was the red line, which got clearance to depart to the southeast. In one incident, the blue line (Grand Canyon Helicopters) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In another incident, the green line (AirStar) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In both cases, I had to alert the departing pilots — on the tower frequency — that I was in their departure path. In one case, I actually began evasive maneuvers when the pilot didn’t appear to hear me. Mind you, the tower had given all of us clearance so we were all “cleared” to depart. Scary, no?

Now look at the picture here. In the first two close call incidents, I was the red line, which got clearance to depart to the southeast. In one incident, the blue line (Grand Canyon Helicopters) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In another incident, the green line (AirStar) got a clearance right after me to depart to the west. In both cases, I had to alert the departing pilots — on the tower frequency — that I was in their departure path. In one case, I actually began evasive maneuvers when the pilot didn’t appear to hear me. Mind you, the tower had given all of us clearance so we were all “cleared” to depart. Scary, no? Let’s look at another close call. In the picture to the right, I was the red line with a clearance to depart to the northeast. The blue line had just gotten a clearance to depart to the northwest. Because he took off before me, we were on a collision course. But I’d been listening and I heard him get the clearance. So when I took off, I kept an eye out for him and made sure I passed behind him.

Let’s look at another close call. In the picture to the right, I was the red line with a clearance to depart to the northeast. The blue line had just gotten a clearance to depart to the northwest. Because he took off before me, we were on a collision course. But I’d been listening and I heard him get the clearance. So when I took off, I kept an eye out for him and made sure I passed behind him. My most recent controlled close call incident was two days ago. I’d gone down to Chandler to meet a friend for lunch. I landed at the Quantum ramp at Chandler Airport (CHD). We had lunch and returned at close to 1 PM — just when Quantum’s training ships were returning. I asked for and got clearance to hover-taxi to the heliport’s landing pad. I then asked for and got an Alpha departure clearance. This requires me to take off from the helipad and follow a canal that runs beside the airport (and helipad) to the north (the red line). When I got my clearance, the tower alerted me to an inbound helicopter that was crossing over the field. I did not hear that helicopter get a landing clearance, but he may have gotten it from Chandler’s south frequency, which I was not monitoring (because I could not). I took off along the canal just as the other helicopter (the purple line) turned left to follow the canal in. We were definitely on a head-on collision course. I saw this unfolding and diverted to the west, just as the tower said something silly like, “Use caution for landing helicopter.” Duh. I told the tower I was moving out of the way to the west. There was no problem. But I wonder what that student pilot thought. Or what Neil, owner of the company, thought as he hovered near the landing pads in an R44, watching us converge.

My most recent controlled close call incident was two days ago. I’d gone down to Chandler to meet a friend for lunch. I landed at the Quantum ramp at Chandler Airport (CHD). We had lunch and returned at close to 1 PM — just when Quantum’s training ships were returning. I asked for and got clearance to hover-taxi to the heliport’s landing pad. I then asked for and got an Alpha departure clearance. This requires me to take off from the helipad and follow a canal that runs beside the airport (and helipad) to the north (the red line). When I got my clearance, the tower alerted me to an inbound helicopter that was crossing over the field. I did not hear that helicopter get a landing clearance, but he may have gotten it from Chandler’s south frequency, which I was not monitoring (because I could not). I took off along the canal just as the other helicopter (the purple line) turned left to follow the canal in. We were definitely on a head-on collision course. I saw this unfolding and diverted to the west, just as the tower said something silly like, “Use caution for landing helicopter.” Duh. I told the tower I was moving out of the way to the west. There was no problem. But I wonder what that student pilot thought. Or what Neil, owner of the company, thought as he hovered near the landing pads in an R44, watching us converge.