There are still opportunities for photography after the sun goes down.

I know I’ve written about this before in this blog, but it’s worth repeating: I like taking photos at night. I like the way the light illuminates the things we don’t notice during the day. I like the weird colors of the light sources. I like the deep shadows and the way some things seem to come out of darkness.

Grand Canyon Village, with its rustic, historic buildings, is one of my favorite places to photograph at night. And since I was so lazy yesterday afternoon, I thought I’d make up for it by taking my camera and tripod for a walk from Bright Angel Lodge, where I’m staying, to the El Tovar Hotel, which just happens to have a nice bar.

These are some of the shots I took along the way.

Outdoor Passageway

The historic Bright Angel Lodge is a series of stone and wood buildings along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. The main lodge building houses the lobby, a museum, restaurants, and various service desks. The other lodge buildings are cross-shaped and house small, simple guest rooms like the one I usually stay in. And then there are cabins with two or four guest rooms per building.

Covered, wooden plank walkways run between many of the buildings. They’re illuminated at night and glow rusty red from the red-painted walls.

Cabin Door

The cabins at Bright Angel Lodge are scattered along the rim. They’re all unique. Some have partial views into the canyon. Others are hidden away among the trees alongside the gravel parking lot.

At night, the doors to some of the cabins glow with a friendly, almost beckoning light. This one, facing into the canyon, seems to await the return of its occupants, who left chairs out front to watch the sunset from their room.

Lookout Studio

Lookout Studio is another of Mary Colter’s designs. This historic building now houses a gift shop. But if you come to the canyon, walk in and through the building. You’ll emerge on the other side, on the top level of a terraced overlook. Climb down for a good spot to watch sunsets or condors or tourists.

The building is lighted mostly from within at night. The wooden trim around its windows is painted a bright teal green.

Light Posts

Subdued lighting lines the path between the main building of Bright Angel Lodge and El Tovar Hotel. The lights are just bright enough to ensure that you don’t trip or bump into a grazing deer or elk along the path at night — but no brighter.

Although they line the path in even intervals, the curve of the path gives them the appearance of random blobs of light ahead.

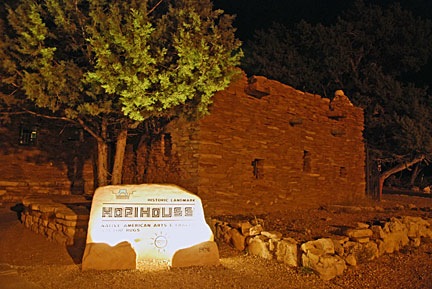

Hopi House

Mary Colter also designed Hopi House, which is currently set up as a gift shop and gallery. She based her design on the architecture of Pueblo indian tribes such as the Hopi. In the old days — the early 1900s — Native American peoples actually lived in upper floors and on the roof of the building.

The building’s stone walls are a textural delight for anyone who admires such things. Set roughly, the stones cast deep shadows on the walls at almost any time of day. At night, things are a bit more subdued.

El Tovar Entrance

El Tovar, which was completed around 1905, is the grand hotel of the Canyon. When finished, it was hailed as the finest hotel in the west.

Made of dark wood with large porches and pitched roofs, El Tovar seems more in place in a densely forested mountain setting than at the rim of a desert canyon. Last night, its sign seemed to glow and its wide open doors welcomed visitors into the lobby.

El Tovar Lobby

The lobby of El Tovar is an impressive collection of mounted wildlife heads, southwestern decor carpets, plus leather sofas in seating areas, and gift shop displays. Last night, a young woman sat in a corner with her laptop, probably surfing the Web — the lobby is one of the few places where WiFi might be available.

I captured this shot with my fisheye lens, which is why it appears distorted around the edges. I like the symmetry of this shot.

Jewelry Case

One of the highlights of El Tovar is this round jewelry case in the middle of the lobby. FIlled with the finest quality, handmade Native American jewelry sparkling under bright lights, it’s like looking into a museum display.

I used my fisheye lens for this shot, too. Although intended mostly as an experiment, I thought it was good enough to share here.

The Best Irish Coffee I Ever Had

By the time I reached this point, it was 9 PM — too late for the martini I had on my mind when I left my room. But I stepped into the bar anyway. It was nearly deserted. I sat at the bar and ordered an Irish Coffee. The bartender made me the best one I’d ever had, complete with a single sugar cube, fresh whipped cream, and a bit of creme d’menthe for color and minty flavor.

When I finished, I set my tripod on my shoulder and walked back to my room. I nearly bumped into a mule deer doe and her fawn along the way.

And yes, I was the only photographer out last night.