A primer for non-pilots.

One of my pet peeves is finding inaccurate information in works of fiction (or non-fiction, for that matter). You can argue all day long that fiction is fiction and the writer can write whatever he wants. After all, fiction, by definition, is a made up story. That gives the author license to make things up as he goes along.

I agree that it’s fine to make up the story, but unless it’s a work of science fiction or fantasy (where it might be acceptable to change the laws of physics), it’s not okay to make up the details of how existing things work. I explored this theme in my post “Facts in Fiction,” and picked apart the work of a bestselling author in “Dan Brown Doesn’t Know Much about Helicopters.” Both posts were triggered, in part, by basic errors about how helicopters work that appeared in works of fiction.

The Question

“Facts in Fiction” was also triggered by an email message I received from a writer looking for facts about how helicopters fly. Oddly, I just received another one of those messages not long ago:

I’ve recently been writing a novel in which I have to describe the sound a helicopter makes, how they fly and things along these lines.

But there is a section of my book where a helicopter runs out of fuel and begins to drop. However, below them is a forest and they crash into the canopy. But in order to minimize damage the pilot uses autorotation to make the helicopter somewhat stable. I don’t want to be an ignorant writer that makes stuff up at the expense of fact. I’ve looked up autorotation but it’s still not clear to me- would you be able to help me out with how a pilot would initiate autorotation (in simple terms!)

Again, I applaud this writer’s desire to get it right. The aviation community certainly doesn’t need yet another work of fiction that misrepresents basic aerodynamic facts.

Unfortunately, it’s pretty clear that this writer does not understand how helicopters fly. This is common among non-pilots. Some folks think that the rotor disc — when the blades are spinning — works like a giant fan that keeps the helicopter in the air. Other folks — well, I don’t know what they think. But very few seem to realize that like airplanes, helicopters have wings.

Yes, wings. What do you think the rotor blades are?

Helicopters are rotary wing aircraft. This means that they have wings that rotate.

The Real Question

Although this writer seems to want an explanation of “how a pilot would initiate autorotation,” he has a bigger misunderstanding to clear up first. It all stems around these two phrases:

…a helicopter runs out of fuel and begins to drop.

and

…in order to minimize damage the pilot uses autorotation to make the helicopter somewhat stable.

The problem is that if a helicopter ran out of fuel and the engine quit (assumed), the pilot has only about 2 seconds to enter an autorotation to prevent a catastrophic crash. You don’t enter an autorotation to “make the helicopter somewhat stable.” You enter an autorotation to maintain a controlled glide to the ground that, hopefully, concludes with a landing everyone can walk away from.

Or, put it another way, in the event of an engine failure, the pilot must perform an autorotation if he wants to survive.

So in order to answer the question this writer asked, I need to first address his misunderstanding of how helicopters fly and what autorotation does.

How Helicopters Fly

Let’s start with something most people do understand — at least partially: how an airplane flies.

An airplane has at least one pair of wings that are fixed to the sides of the fuselage. The wings have a specific shape called an airfoil that makes lift possible.

When the pilot wants to take off, he rolls down the runway, gathering speed. This causes wind to flow over and under the airfoil. After reaching a certain predetermined minimum speed, the pilot pulls back on the yoke or stick which lifts the airplane’s nose. This also changes the angle of attack of the relative wind on the wings. That change produces lift and the plane takes off.

Obviously, this is an extremely simplified explanation of how airfoils, relative wind, and angle of attack produce lift. But it’s really all you need to know (unless you’re a pilot).

A helicopter’s wings — remember, they’re rotary wings — work much the same way. But instead of moving the entire aircraft to increase the relative wind over the airfoil, the wings rotate faster and faster until they get to 100% (or thereabouts; long story) RPM. Then, when the pilot wants to take off, he pulls up on a control called the collective which increases the pitch or angle of attack of all the rotor blades. That change produces lift and the helicopter takes off.

It’s important to note here that when you increase angle of attack, you also increase drag. Whether you’re in an airplane or in a helicopter, you’ll need to increase the throttle or power setting to overcome the increased drag without decreasing forward speed (airplane) or rotor RPM (helicopter).

If you’re interested in learning more about lift and how helicopters fly, I highly recommend a free FAA publication called Rotorcraft Flying Handbook. This is a great guide for anyone interested in learning more about flying helicopters. You don’t need to be an aeronautical engineer to understand it, either. If the text isn’t enough to explain something, the accompanying diagrams should clear up any confusion. I cannot recommend this book highly enough.

If you’re interested in learning more about lift and how helicopters fly, I highly recommend a free FAA publication called Rotorcraft Flying Handbook. This is a great guide for anyone interested in learning more about flying helicopters. You don’t need to be an aeronautical engineer to understand it, either. If the text isn’t enough to explain something, the accompanying diagrams should clear up any confusion. I cannot recommend this book highly enough.

What Happens when the Engine Quits

Things get a bit more interesting when an aircraft’s engine quits.

On an airplane, the engine is used for propulsion. If the engine stops running, there’s nothing pushing the airplane forward to maintain that relative wind. Because it’s the forward speed that keeps an airplane flying, its vital to maintain airspeed above what’s called stall speed — the speed at which the wings can no longer produce lift. To maintain airspeed, the pilot pushes the airplane’s nose forward and begins a descent, thus trading altitude for airspeed. The plane glides to the ground. With luck, there’s something near the ground resembling a runway and the airplane can land safely.

On a helicopter, the engine is used to turn the rotor blades. If the engine stops running, there’s nothing driving the blades. Because it’s the spinning of the rotor blades or rotor RPM that keeps a helicopter flying, its vital to keep the rotor RPM above stall speed. The pilot pushes the collective all the way down, thus reducing drag on the rotor blades — this is how he enters autorotation. (The helicopter’s freewheeling unit has already disengaged the engine from the drive system, so the blades can rotate on their own.) The reduction of the angle of attack of the blades starts a descent, trading altitude for airspeed and rotor RPM. The helicopter glides to the ground. With luck, there’s a clearing or parking lot and the helicopter can land safely.

It’s extremely important to note that as long as the pilot maintains sufficient rotor RPM, he has full control of the helicopter all the way down to the ground. He can steer in any direction, circle an appropriate landing zone, and even fly sideways or backwards if necessary (and he has the skill and nerve!) to make the landing spot. So to say “the pilot uses autorotation to make the helicopter somewhat stable” shows complete ignorance about how autorotation works.

About 30 feet above the ground, the pilot pulls back on the cyclic to slow his forward airspeed. The resulting flare trades airspeed for rotor RPM, thus giving the main rotor blades extra speed. That comes in handy when he levels the helicopter and pulls the collective full up — thus bleeding off RPM, which he won’t need on the ground — to cushion the landing before touching the ground.

The point that needs to be made here is that helicopter engine failures and autorotations don’t always end in a crash. In fact, with a skilled pilot and a suitable landing zone, there’s no reason why it should end in a crash. So in the example presented by this writer, the helicopter doesn’t have to crash at all. It could have an engine failure and safely land in a clearing.

And here’s another newsflash: every helicopter pilot not only knows how to perform an autorotation, but he’s tested on it before he can get his pilot certificate. He’s also required to prove he can do one every two years during a biennial flight review. And if he’s like me, he’s tested annually by an FAA inspector for a Part 135 check ride.

Writers: Do Your Homework!

It’s good to see this writer trying to get the information he needs. But in my opinion, he went about it all the wrong way.

It’s been over a month since I got his emailed request for information. I never replied by email; this is my reply. Has he written his passage without the answers to his question? I have no idea. He never followed up.

But wouldn’t it have been smarter to simply talk face-to-face with a helicopter pilot? Any helicopter pilot could answer these questions and set him straight. Helicopter pilots aren’t so hard to find. Flight schools, tour operators, medevac bases, police helicopter bases, etc. Not only could the writer get his questions answered by someone who knows the answers from experience, but he could gather a wealth of information about helicopters, including their sound, why they don’t usually take off straight up, and other operation aspects. And if he visited a flight school or tour operator and had some extra money to spend, he could even go on a flight to see what it’s like from the inside of the aircraft.

Emailing a blogger who happens to write a lot about helicopters and complain when novelists get it wrong [hand raised] is downright lazy.

And despite what you might think, writing is not a job for lazy people.

Pack a clean, dry canning jar with as many cherry pieces as you can. Because I had all those Rainiers that were starting to get a little old, I layered them in the middle of the jar (Al’s idea) which made each jar a little more interesting looking than if it had been packed with just red or yellow cherries.

Pack a clean, dry canning jar with as many cherry pieces as you can. Because I had all those Rainiers that were starting to get a little old, I layered them in the middle of the jar (Al’s idea) which made each jar a little more interesting looking than if it had been packed with just red or yellow cherries.

Pack a clean, dry canning jar with as many cherry pieces as you can. Because I had all those Rainiers that were starting to get a little old, I layered them in the middle of the jar (Al’s idea) which made each jar a little more interesting looking than if it had been packed with just red or yellow cherries.

Pack a clean, dry canning jar with as many cherry pieces as you can. Because I had all those Rainiers that were starting to get a little old, I layered them in the middle of the jar (Al’s idea) which made each jar a little more interesting looking than if it had been packed with just red or yellow cherries. How much do you think you can squeeze into one of these?

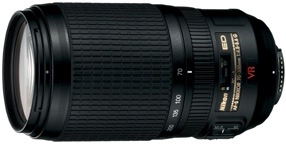

How much do you think you can squeeze into one of these? Telephoto lens. I have a Nikon ED AF-S Nikkor 70-300mm 1:4.5-5.6 G VR lens that I use for just about all of my bird photography. Again, not a professional lens and, as some have argued, not even a long enough lens for serious wildlife photography. But hell, this is a hobby. You have to draw the line somewhere. What makes this lens especially useful is the vibration reduction (VR) feature, which kicks in as necessary when turned on.

Telephoto lens. I have a Nikon ED AF-S Nikkor 70-300mm 1:4.5-5.6 G VR lens that I use for just about all of my bird photography. Again, not a professional lens and, as some have argued, not even a long enough lens for serious wildlife photography. But hell, this is a hobby. You have to draw the line somewhere. What makes this lens especially useful is the vibration reduction (VR) feature, which kicks in as necessary when turned on.

Another pair of must-have publications is the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) and Auronautics Information Manual (AIM) which are often published in the same volume. The FAR is updated throughout the year and most publishers publish new editions annually. You should get the most recent edition when you begin your training and try to update it at least every two years. Or do what I do: buy it in app format for an iPad (shown here) or iPhone. You can find them both on

Another pair of must-have publications is the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) and Auronautics Information Manual (AIM) which are often published in the same volume. The FAR is updated throughout the year and most publishers publish new editions annually. You should get the most recent edition when you begin your training and try to update it at least every two years. Or do what I do: buy it in app format for an iPad (shown here) or iPhone. You can find them both on  There are other books about flying helicopters. Many of them have been written by experienced helicopter pilots. One of my favorites is

There are other books about flying helicopters. Many of them have been written by experienced helicopter pilots. One of my favorites is  If you’re interested in learning more about lift and how helicopters fly, I highly recommend a free FAA publication called

If you’re interested in learning more about lift and how helicopters fly, I highly recommend a free FAA publication called