Cut short by a tragic disaster.

The second day of my job got off to a weird start. Although I was supposed to be at the client site at 8 AM, a family emergency had me driving toward Phoenix at 7:10 AM — the same time I should have been driving to the airport to get the helicopter. I wasn’t happy about this; it meant I’d be at least 3 hours late for work. Although my client was understanding, I wasn’t. The mission I was sent to accomplish — get two stranded people to Sky Harbor Airport in time for a 9 AM flight — was impossible to achieve in the time allotted. So not only was I going to let down a good client, but I was doing it for no good reason.

Fortunately, the two stranded people were able to make other arrangements. I was only 5 miles south of Wickenburg’s town limits when I got the call and was able to turn around. I arrived at the airport at 7:30. Even after removing the tie-downs, preflighting, hooking up the helicopter’s nosecam, starting up, warming up, and making the flight, I’d still be there within 15 minutes of my originally scheduled arrival time.

Nothing much was going on at Wickenburg Airport that morning — although there was a twin and a small jet parked in the jet parking area. I took care of business, made my radio calls, and took off to the west.

Along the way, I tried to notice things that I hadn’t noticed before — things I hadn’t included in yesterday’s blog post about Day 1. I realized that there weren’t nearly as many areas of carved water channels as I remembered. And I noticed cow paths. Other than that, there was nothing different, nothing to add to yesterday’s report.

I did a much better job bleeding off airspeed before coming into landing. The day before, I’d spotted an alternative landing zone that was must closer to the “town.” There were only two drawbacks that I could foresee: they were closer to the horse corrals, so I’d be more likely to frighten the horses, and it was much closer to the road, so I’d be more likely to stir up dust. I decided to give it a try.

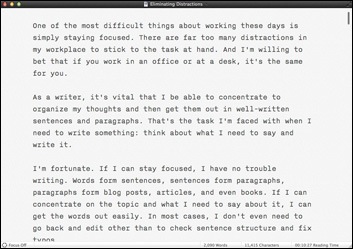

This “nose cam” shot from my final approach shows my landing zone (on right, beyond cactus) and the whole town, including the hotel.

As I approached, I began having doubts about the clearance between my main rotor blades and a palo verde tree at the edge of the landing zone. It had certainly seemed like enough space when I walked past the day before. I knew that judging distances could be tricky when airborne and decided to trust my initial thoughts about the spot. I kept coming.

The dust started kicking up when I was still 50 feet up. Not exactly brownout conditions, but a lot more dust than I like to see. Out of the corner of my eye, I noticed two of the horses prancing around a bit as the dust cloud approached them. Not exactly panicking, but far from calm. I wondered if the dust would make it all the way into town.

Knowing that the best way to make the dust stop blowing was to get on the ground and throttle down to idle power, I expedited my landing. The spot I picked was level and firm. I cut the throttle and, as predicted, the dust stopped churning. By the time I was tightening up the control frictions, the horses had already calmed down.

I had plenty of clearance from all obstacles.

My parking spot on the second day was much closer to town.

I shut down and let the blades spin to a stop while I removed the two back doors. My clients used the back seat area of the helicopter for their equipment and we worked with the doors off. I figured I’d make up for being 10 minutes late by having the helicopter all ready for them when they came out with the equipment.

Not that anyone came running out to meet me. They usually don’t.

I grabbed my gear and headed to the cafe. Along the way, I saw some familiar faces and was greeted with a few waves and hellos. Inside, I met with my main contact and explained the family emergency that had prompted my phone call an hour before. Then I grabbed a glass of orange juice and went out to track down the folks who would be installing equipment in the helicopter.

The Equipment Installation

The tech folks were based in another part of the long building that had been set up like an old fashioned soda fountain. Most of the people reading this probably never even saw the real thing — they just don’t exist in many places anymore. This was made with components taken from real soda fountains — countertop, simple round bar stools, ice cream bins, syrup pumps, blenders, malt dispensers. Most stuff dated from the 1940s through the 1960s. None of it was set up for use anymore; every cabinet and bin was used to store paper and brochures and gift shop items. There were a handful of booths, each of which were being used to stage equipment. The walls were lined with gift shop items, all of which had likely been there at least five years. Some of the items were older than me.

I found the first tech almost immediately. He had a remote controlled camera head that he needed installed. It was part of a kit that included a 50-pound customized Pelican case containing a battery and some electronics. He configured and tested it while I waited, then showed me how he could control the camera head with his iPhone. Cool. We carried it out to the helicopter and found a good place for it on the front passenger seat. I got a few instructions about how to turn it on at flight time and we headed back to the soda fountain.

The antenna/radio guys were next. I watched them assemble and mount their equipment, tested occasionally to make sure it was mounted firmly, and picked up snipped wire ties as they dropped them in an effort to keep my landing zone FOD-free.

By 9:30 AM, the equipment was all set up in the helicopter to everyone’s satisfaction. For purposes of client confidentiality, I don’t share photos of their equipment or setup.

The Wait

Then the waiting began. The helicopter was just part of the testing process; there were vehicles and personnel vests to be configured, too. I knew from experience that this could take hours, but I hoped it wouldn’t be that long.

I took my camera out and began wandering around in the immediate area, shooting images of the few wildflowers that grew beside some of the old iron mining and farming equipment. It was a disappointing spring; wildflowers were limited to desert marigold, some brittlebush, and another yellow flower that might have been desert senna. There were also a few small pale purple flowers. The globe mallow were just starting to bloom. Hedgehog cactus should have been in full bloom, but I didn’t see any anywhere. Ditto for poppies.

I spent about 45 minutes wandering around, trying to get good images. I’d run out of the house that morning without my tripod or monopod, so I set the camera for shutter speed priority and set the shutter speed to 1/1000 second. With full sun on yet another cloudless Arizona morning, there was certainly enough light. But I also got the narrow depth of field that I like when shooting flowers close up. The only disappointment was the lack of flowers to shoot. After a while, I began concentrating on all that old metal equipment.

I had a chat with the cowboy, who was messing with the hardware on the flagpole. I mentioned how I’d scared the horses a bit but they seemed okay. He told me to fly right over them. He and I both knew that the best way to get a horse used to some unusual noise or activity was to subject them to it until they began ignoring it. I had no real desire to overfly the horses, but was glad he’d offered it as an option. That direction was one of two possible “escape routes” if my landing started going south and I needed to do a go-around.

Not wanting to wander too far away from the techs, I returned to the soda fountain, found a table on the far side of the room, took out my laptop, and began reviewing photos and writing this blog post. I’d come prepared for a long wait.

I should mention here that although the place is off the grid, when this client comes, they set up a multi-node network that includes broadband Internet access. So not only could I compose a blog post, but I could check Twitter and Facebook and email. This was a good thing because my cell phone signal was very weak and 3G wasn’t really an option.

The Flight

At 11:30, it looked as if we might actually have a flight before lunch. I headed out to the helicopter and was surprised when two men I’d never seen before approached and announced they’d be flying with me. The reason I was surprised was because I knew one of the techs was planning to fly with me so he could monitor the equipment during the flight on his laptop — that was the usual procedure. But with the camera up front, I only had two passenger seats open in back.

What followed was some minor confusion. The tech told me we’d run the first flight as a sort of dry run for the actual tests, which would be done after lunch. He told me to take the other two men. So I briefed them, loaded them on board, and strapped them in. Then I started up and, during my warm-up processed, pushed the appropriate buttons on the camera equipment sitting beside me. A while later, I lifted off in a cloud of dust, made a 180° turn, and departed down the road, pushing the cyclic forward to accelerate as quickly as possible to clear the dust.

My job was to keep maintain a line of sight with the SUV on the road below me and the main building back in town. My passengers would monitor internet connectivity in the helicopter — yes, we were set up as a WiFi hotspot.

The flight lasted about 15 minutes. The biggest challenge was flying slow enough that I didn’t blow past the SUV and need to keep circling. There was just enough wind coming into the back seat headset mics to force me to turn off the voice activated intercom.

I watched the SUV pull off the road and make a U-Turn. I circled slowly, 500 feet above them. Then my phone rang. It was the tech back at the base, calling me back. They were done with this first test.

I headed back, leaving the SUV behind and landed in my spot. The dust cloud really was outrageous. The wind was blowing at about five mph from behind me — yes, I made a tailwind landing — and the dust kept getting blown into the town area. It didn’t go as far as the cafe, but it did seem to go as far as the soda fountain. No one had complained, though. I think they liked having the helicopter closer, where it was quicker and easier to get to than my old landing zone.

I let my passengers get out while I was still shutting down. Then, since it was already after noon, I headed back to the cafe, where I knew Rosa would have one of her excellent lunches. I found a seat among the techs and one of the long table and soon had a barbecue beef sandwich, cole slaw, and chili in front of me. During lunch, we talked about helicopter and the cherry drying work I do in Washington in the summer. That led to other conversations about weird helicopter work and weird helicopter flights.

I was just finishing desert when my contact stepped into the cafe. She had her phone against her ear, but she was addressing everyone in the room when she said calmly, “You guys might want to move your cars. The hotel is on fire.”

The Fire

We all cleared out of the building and into the street out front. I was expecting to see a thin trail of smoke coming from the building. Instead, the top right of the three-story building was engulfed in flames at least 10 feet high. Guys started running toward it while I ran back into the cafe, not willing to see what was happening. Rosa was there, looking at me, and I told her what was happening. She ran out to look and I followed her.

It was the most amazing thing. The fire spread at the rate of about one room per minute, moving right to left across the top floor of the hotel and then down. The rental cars parked at the base of the building were smoldering; as I watched, the hood of one burst into flames. I could feel the heat of the fire from the end of the main building. Guys who had tried too late to retrieve belongings from their hotel rooms were turned back while a handful of other guys ran back toward us holding scattered possessions in their hands. Thick black smoke climbed into the sky. Huge sheets of the hotel’s metal roof lifted into the sky like aluminum foil.

The hotel at Robson’s just minutes after the fire started.

And there was nothing we could do. There were no hoses, no water spigots. It was clear from the start that the hotel was a goner, but the intense heat began to spread the fire closer to us, into the wind. The dry wood frame of a nearby building caught fire. Then another on the other side of the hotel, right beside one of the caretaker homes.

In less than 15 minutes the whole building was on fire and the fire was spreading. The truck in this shot was lost; no one could get near it.

The local fire department showed up just as another row of buildings caught fire. They’d brought two tanker trucks filled with water. They drove up the street as far as they could and got to work. One firefighter came toward us and told us to clear out of town.

In the background, we could clearly hear the sound of the rental car fuel tanks exploding.

The firefighters concentrated their efforts on the buildings that could still be saved, mostly to prevent the spread of the fire. I think that if they’d arrived ten minutes later, the whole town would have been lost.

We gathered in a group near the entrance to the town while additional firefighting equipment rolled in. My client had already gone through their list of participants. No one was missing. One guy had been burned running from the fire after retrieving some of his belongings. He’d used his arm to shield his head from the heat and his arm had gotten what were probably second degree burns. No one else was injured.

We all realized that if the fire had broken out at night, people would have been killed. It just spread so quickly.

It was obvious that the event was over. They began making arrangements to leave. At least six cars had been lost; they’d need to carpool back to Wickenburg and Phoenix. They came out to the helicopter and pulled their equipment off. I put the doors back on and prepared to leave.

Back in town, the hotel had been reduced to a single floor of burning rubble. One of the tanker trucks rolled out of town, empty, while another one rolled in.

The Flight Home

I took off in one final cloud of dust. But rather than head right back to Wickenburg, I circled around the back of the townsite to see if the fire had spread into the desert. After all, the wind was blowing that way. I was very surprised to see several other wooden buildings quite a distance away from the hotel completely burned to the ground and still in flames, obviously ignited by sparks. I paused just long enough for the helicopter’s “nosecam” to get a shot, then banked away to the east and headed back to Wickenburg Airport.

The flight back was uneventful. I didn’t pay much attention to my surroundings. I was feeling stunned and saddened by the loss of the old hotel. I knew the original owner would be heartbroken when she found out.

I also knew that it was the end of an era out in Aguila. The hotel would not be rebuilt; without it there wasn’t much to attract the groups that the owners needed to make it financially feasible. My client would not likely return; it was too far away from the closest overnight accommodations in Wickenburg to be convenient. I might not ever work for them again.

It was a hell of a way to end a job.

The original owner was apparently obsessed with collecting old mining and farming equipment — I can’t imagine a larger collection anywhere else in the world. It’s mostly heavy metal stuff made of iron so thick that even the rust can’t hurt it. White numbered boards precariously attached to some of the more interesting items serve as reminders of the walking tour visitors were encouraged to take.

The original owner was apparently obsessed with collecting old mining and farming equipment — I can’t imagine a larger collection anywhere else in the world. It’s mostly heavy metal stuff made of iron so thick that even the rust can’t hurt it. White numbered boards precariously attached to some of the more interesting items serve as reminders of the walking tour visitors were encouraged to take.