The truth can now be told.

Here’s Pete and Linda helping me do a pre-purchase inspection last fall.

For a while, I was doing a lot of tweeting and Facebook updating about my little boat. It’s a 1995 Sea Ray Sea Rayder F-16. Sounds hot, huh? Well, it’s just a little old 16-foot jet boat that can take up to 750 pounds of payload spread among five seats — about the same capacity as my helicopter, with one extra seat.

The mobile mansion at one of two overnight stops on the way back to Arizona last October.

I’d bought it in Washington State last autumn, just before going back to Arizona for the season. Because I had to tow my “mobile mansion” back to Arizona, I had to leave the boat behind. The folks I bought it from kindly agreed to store it form me. I regretted not taking it home; I didn’t use the mobile mansion in Arizona over the winter, but I sure could have used that boat.

Taking Possession

In the spring, I returned to Washington for cherry drying season. I came back early, mostly because I like it up here so much better than Arizona. In fact, I’m seriously considering relocating.

I finally took possession of my little boat early in May. I towed it back to the campground where I was living.

Here’s my little boat, parked at the campground where I’m living right now. That’s my mobile mansion in the background, with the windsock.

The boat needed some work, but not much. The bumper around the edge of the boat was cracked in front and I wanted to replace it. The grip stickers on the engine lid were half peeled off and I wanted to replace them, too. The wires for the trailer lights were frayed and patched and needed to be fixed up. The trailer wheel bearings likely needed repacking with grease for the long drive back to Arizona. And the bimini top had two broken parts that had to be replaced before I could use it. I set about taking care of these things, making an appointment at a boat dealer for some and ordering parts for others.

I also bought a river anchor and some line for it, just in case the engine decided it didn’t want to run when I was out on the water. I didn’t want to end up at the next dam.

The Planned Test Run Doesn’t Go as Planned

The weather warmed and the winds calmed. In mid-month, we had two consecutive days forecasted with unusually warm weather and light winds. It would be a perfect opportunity to take the boat out for a test run.

I admit that I was nervous about taking the boat out by myself. I had plenty of confidence in the boat’s seaworthiness — its previous owners had taken good care of it. But it had been a long time since I’d ever launched a watercraft — jet skis at least 5 years ago — and I’d never done it alone. I asked my friend Pete to accompany me to the boat ramp and advise me while I launched the boat.

Pete’s schedule was tight, with just an hour-long gap between appointments, so my goal was to prep the boat and get it all ready to launch before we met. I hooked it up to the truck and stripped off the boat cover. I got all my gear together, including a bag of goodies to snack on. Then I hopped in the truck and started the 15-mile drive to Crescent Bar, stopping to fill the boat’s gas tank with gas along the way.

Crescent Bar from the air. You can see (and buy) a larger version of this image here.

Crescent Bar is a resort area near Quincy, WA. It’s right on the Columbia River — a narrow strip of land stretching downriver. Half it it is an island, connected to the mainland with a little bridge. There’s a boat ramp and a handful of slips near the bridge. This is just one of a few access points for Wanapum Lake, the stretch of Columbia River between the Wanapum and Rock Island dams.

It’s an interesting body of water. I’ve seen it as smooth as glass on a windless day. But I’ve also seen it whipped up to whitecaps when the wind howls down the river between the cliff faces.

This is where I’d do most of my area boating.

To reach Crescent Bar from Quincy, you have to drive down two hills. The first, on Route 28 is a steep 60 mph road with one lane downhill and two uphill. It’s relatively straight and very smooth. The second is the side road that winds down the cliffs to Crescent bar.

I was doing about 55 miles per hour down that first hill when I caught a flash of white in my rear view mirror. I didn’t see anything when I looked — at least at first. Then I noticed the car behind me, which was about 10 car lengths back, was taking evasive maneuvers. And then I saw something white skidding across the road.

I knew immediately what it was: the engine lid from my boat.

You see, the engine lid opens from front to back (consult first photo on this post) so you can access the engine compartment while you’re on the water. It was held down with two latches. I thought they’d been latched. The boat cover, which snaps over the front part of the engine lid, also helps to hold the lid down by preventing air from getting under the lid. But I’d removed it to speed up the launch process.

I stopped the truck on the side of the road, shut down the engine, and put on the emergency flashers. I looked back and could see the engine lid in the left uphill lane about 1000 feet away, just lying there. I could imagine a semi truck running it over and shattering it into a million pieces. So I ran.

I didn’t know I could still run. I didn’t do it very well. I certainly won’t be signing up for any races soon. But I got up there before any uphill traffic. Then I grabbed the engine lid and carried it to the side of the road.

It was awkward and heavy. But it was also in one piece. I examined it when I reached the safety of the roadside. It had hit the pavement in one corner and slid on its top. The fiberglass was slightly smashed in the corner and scratched like hell on the top. The big hinge had been ripped off the back; I assumed (correctly) that it remained on the boat.

I began the long walk back to the truck, glad it was all downhill. I was winded. I was able to carry my burden by grasping it from two round cutouts in the bottom side. Still, I could only take about 50 steps before I had to rest. The damn thing was heavy.

A car stopped just past my truck and a guy got out. He walked up the hill and met me when I was halfway back.

“Looks like you can use a hand,” he said.

Who says there aren’t any Good Samaritans anymore?

It was easier with each of us grasping the lid by one of the round holes. He helped me lift it into the bed of the pickup. We looked back at the boat and the gaping opening over the engine. The hinge, which was attached to a piece of wood, was still there. So were the two hydraulic lift arms. But the damage was extensive — not something that could be fixed easily, like with duct tape.

I thanked my helper and watched him go back to his car and continue down the hill. I made a U-turn and headed back to Quincy. I stopped at my friend Pete’s house, where he was just finishing up with one of his appointments. We fitted the lid back on the engine. It fit nicely, but wouldn’t stay on its own. Pete gave me a strap to hold it down. I went home, feeling very stupid.

Repairs

I worked the phones. The local boat shops weren’t interested in helping me, but one of them recommended an auto body shop that does fiberglas work.

A few days later, I got an estimate at Earhart’s Collision Repair. The initial estimate, which would make the engine lid “good as new,” was $1,500. Ouch. I asked if there was a way to make it less. He redid the estimate without painting and managed to cut it in half. I considered that my “stupidity tax.” I left the boat with them.

It was a week before the boat was done. In the meantime, I’d gotten the bimini top parts I needed to repair the top. The boat dealer got the parts they needed to do the rubber bumper.

I picked up the boat at Earhart’s. It looked great. The repair was very well done and the lid was fully functional. Well, except for one of the latches, which had broken and was on order with a Sea Ray dealer in Arizona.

I took the boat across the river to the boat shop and left it with them for the rubber bumper and trailer repairs. I told them that since the lid was scratched up, I wasn’t interested in the no-slip stickers. I offered to pay for them — since they’d been a special order — but they said they’d put them on the shelf for others to buy.

The next day, I picked up the boat and brought it back to the campground. I was back to square one.

Still on dry land, but at least the top works.

I spent a few hours repairing the bimini top’s frame and installing new hardware on the boat for it. I put the top up. It looked and worked great.

Second Try

I watched the weather carefully. Memorial Day weekend was pretty good, but Crescent Bar gets crazy on weekends and I wasn’t interested in making my first outing an ordeal. And then I had to wait until Pete or Linda (who had sold me the boat) was available to supervise. Schedules were tough.

I almost went out on Thursday afternoon by myself. But I chickened out.

On Friday, Pete and Linda were both busy, but Pete could pull away if he had to. I decided to give it a go by myself and call him only if I needed help.

So once again, I made the trip down to Crescent Bar. This time, with the lid firmly strapped on, I had no mishaps. It was about 3 PM when I got there and there weren’t many people around. I prepped the boat by stripping off the straps and cover. I loaded a canvas bag with a bit of extra gear — towel, long-sleeved shirt, bottled water, phone in a zip-lock bag, etc. I took my time.

Because I was by myself and the launch area was very small, I’d have to cast off from the dock while sitting at the wheel. I’d fastened a length of line to the steering wheel — the boat doesn’t have any cleats! — and secured the long end of the rope to a cleat on the dock. I didn’t want the boat floating off without me once it was off the trailer. Then I backed the boat trailer into the water on the right side of the wooden dock. I did it slowly and stopped gently just as the trucks back wheels touched the water. The boat floated slowly off the trailer.

I got out of the truck, walked out onto the dock, and used the rope to pull the boat to the dock. Then I used the short end of the rope on the steering wheel to secure the boat tightly to the end of the dock.

So far, so good.

I pulled the trailer out of the water and parked it. I locked the truck and went back to the boat.

By this time, another couple had arrived with their boat and were launching it. They had some trouble getting it started. But not as much trouble as I had. The reason: I had forgotten how.

I’d only been out in the boat once and I admit that I hadn’t been paying close attention to the starting process. I knew I had to stick in the key and I knew I had to attach a safety clip designed to shut down the engine if the driver falls out. (Jet skis have these, too.) But what else?

Fortunately, I had downloaded the boat’s Operator’s Manual from the Sea Ray website. It was a PDF created from a scan, but it was perfectly legible on my iPad. I zipped to the instructions and followed them. After running the blower for a few minutes, I turned the key and pushed the starter rocker button. The engine cranked. It took five tries before it caught. Then it idled noisily like most boat engines do.

And that’s when I realized that “idle” on my little boat didn’t really mean idle. Even though the boat’s throttle was in neutral, the boat was trying to move, pulling hard on the rope that attached it to the dock’s cleat. I was able to get some slack in the rope and disconnect it. Then the boat motored slowly toward the bridge.

Driving a boat isn’t like driving a car. You must have motion — forward or backward — to steer it. On a jet boat, motion isn’t enough. Because there’s no rudder, you must have powered motion. It’s the thrust of the engine that steers the boat. So the slower you go, the harder the boat is to steer.

The steering wheel on my boat doesn’t have much movement. It only goes about 30° in each direction. When I didn’t get an immediate response, I assumed the steering wasn’t working right. But that wasn’t the case. It just was very slow to react. So I just kept overreacting.

One of my Facebook friends compared it to trying to hover a helicopter for the first time. He’s right, but backwards. In a helicopter, you over control because the controls are just so damn sensitive. In this boat, you over control because nothing seems to be happening.

I nearly hit the rocks on the opposite side of the channel. I used reverse throttle to get myself out of there. Then forward a bit faster than I should have to get away from the dock area.

Out and About

I headed out toward the river. The wind had kicked up and there were waves 1-2 feet high. I puttered out, trying to drive at the No Wake speed I was supposed to be at. Then I cleared the No Wake area and gunned it. The boat bounced along in the waves.

I was still having trouble with steering — and that’s because of the way jet boats steer. They fool you into thinking that they’re just like any other boat, but, in realty, they steer like jet skis. When you steer a boat, boat turns kind of like a car, leaning into the curve as it moves. When you steer this jet boat, however, it kind of slips into the curve with very little body roll. It’s extremely disconcerting — at least at first. With the bumpy water, it wasn’t a very good feeling.

I decided to head across the river to calmer water near West Bar, an undeveloped piece of land on the inside curve of the river. I got there quickly, slowed down, and then idled down, pointing upriver.

My phone rang. It was Pete. I got it out of its zip-lock bag and answered. He was down at the dock; he’d come down to see if I needed help. I asked him if I needed to run the blower while the boat was running. He told me I could shut it off. He also told me that the wind was kicking up and the water was rough upriver. He suggested that I go on the other side of the island where the water was calmer.

Good idea. I thanked him, hung up, and stowed my phone. Then I headed back across the river again. It seemed even rougher. The boat jumped on the waves. The water came up and splashed me in the face. I was glad it was a warm day.

I slowed to No Wake speed, passed under the bridge again, and continued to the narrow strip of water between the island and the cliffs. The water was dead calm. I experimented with different power settings. At first, I thought the slowest I could go while remaining in control was with the engine at 1600 RPM. But I played around some more and soon got good controlling the boat at “idle” speed: 1000 RPM.

I went all the way out to the end of the island, past the leased homesites and golf course. I shut off the engine and drifted in the still water, enjoying the sudden silence and hearing, for the first time, the birds and frogs in the cliffs and water around me. I also spotted a family of Canada geese, feeding along the island’s shore. I could imagine spending hours drifting like this, maybe with the stereo on low, the top up, and a book in my hand. There’s something about being out on the water…

But I was thinking about what would come next: docking the boat and getting it out of the water — by myself. I realized that to pull it off, I’d have to come in slowly and be able to put the dock’s cleat right next to my seat at the steering wheel. With the wind blowing, I wasn’t sure whether I could do it.

So I decided to practice before going back. I restarted the engine — it came to life immediately. Then I picked various points along the shore and pretended that they were my docking spot. I’d aim for them, compensating for the wind. Just before I reached them, I’d put the boat into reverse and bring it to a stop. Then I’d back away and do it again at another point. I did this four times and got better with every try.

It was time to go back.

Docking

Before heading in, I fastened a long line to a round tow point at the front of the boat and secured the line, neatly wrapped, in one of the grab handles up front. Then I fastened a much shorter line to the steering wheel.

I motored in slowly. Several times, I was tempted to pick up the pace, but somehow I knew that patience was the key.

Understand that I’ve been on various boats and water craft many times in my life. My parents had a series of small motor boats for Hudson River excursions starting when I was about 10. When my mother remarried, she talked my stepdad into getting a boat; their last boat was a 28-foot Bayliner with a cabin. I’ve driven all of these boats. I’ve also driven various watercraft from dinghies to houseboats.

During that time, I’ve seen plenty of bad docking. I remember one trip across the Long Island Sound from Kings Park to someplace in Connecticut when my stepdad came in way too fast and gunned it in reverse just in time to prevent damage to either the dock or our boat. Spectators really enjoyed that. Another time, one of my companions nosed a houseboat into a dock at Lake Powell’s Dangling Rope Marina so hard that I thought the dock might break loose. In each case of bad docking I could remember, the problem had been speed: too much of it.

So I was going to take it slowly.

I was glad — at least at first — that there was no one around to witness my approach and docking. I floated forward, right on target the entire time. I pulled back on the throttle until I was at idle speed. Then the cleat was within reach of my hand. I nudged the throttle to reverse to stop the boat, grabbed the cleat, and secured the line around it.

It had been a perfect approach and docking. The best I’d ever seen. Certain the best I’d ever done.

Where were the witnesses when you wanted them?

I stepped out onto the dock, took the rope fastened to the bow, and tied it to a cleat halfway up the dock. The boat was now secured in two places. Time to get the trailer.

I think the hardest thing I did that day was back the empty trailer down the ramp. Trouble was, because it was so low, I simply couldn’t see it. It took about 10 tries to get it in position.

Then I walked back down the dock, unfastened the rope at my seat, and then unfastened the long rope. I walked around the dock to the front of the trailer and pulled the boat in. I got it close enough to attach the hook for the crank and cranked it the rest of the way. Easy.

I pulled the boat out of the water and away from the ramp so I wouldn’t block others. Then I took my time fastening the boat back down to the trailer and putting the cover back on.

Mission Accomplished

My main purpose in going out on the boat yesterday was to develop some kind of procedure for launching and later docking the boat by myself. I knew there would be special challenges that crews of two or more don’t have to deal with. I wanted to make sure I knew what needed to be done and come up with a way to do it all alone.

I honestly didn’t expect it to go as well as it did. The launching and docking went better than I could have imagined. Starting the boat and driving it out had been the big challenges — but by taking my time and working hard to do it right I’d been able to rise to those challenges. I now knew exactly what to expect — and how to deal with it.

Pete nailed it when he pointed out, later in the day, that it had been a confidence builder. The next time I go out, I’ll likely go farther and enjoy myself even more.

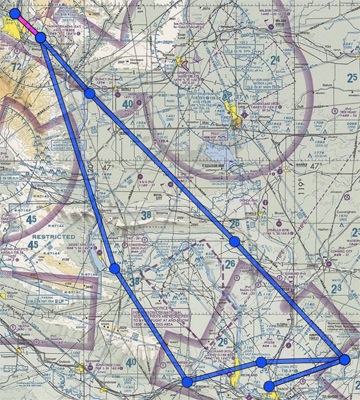

The plan I came up with (illustrated here) was to visit the first four properties, which would take us to our farthest point from home. While my clients tended to business at that last property, I’d buzz over to the airport to get fuel. Then I’d come back to get them and we’d hit the other two properties on the way home. This fit in well with my client’s plan.

The plan I came up with (illustrated here) was to visit the first four properties, which would take us to our farthest point from home. While my clients tended to business at that last property, I’d buzz over to the airport to get fuel. Then I’d come back to get them and we’d hit the other two properties on the way home. This fit in well with my client’s plan. Of course, the very first landing zone was going to be a problem. It was in truck loading zone on the side of a hill. There were various obstacles in three directions and a steep approach/departure was required. This was my client’s workplace (or near it) and he wanted me to pick up him and his companions there.

Of course, the very first landing zone was going to be a problem. It was in truck loading zone on the side of a hill. There were various obstacles in three directions and a steep approach/departure was required. This was my client’s workplace (or near it) and he wanted me to pick up him and his companions there. Now, I like to be able to put the biggest person up front with me. Big people usually need more space, including more legroom, and the front seat has more legroom. But when I put 240-pound A up front with me, the CG plot points were outside the envelope. That means that I might not have enough aft cyclic to arrest forward motion. In other words, I might not be able to stop.

Now, I like to be able to put the biggest person up front with me. Big people usually need more space, including more legroom, and the front seat has more legroom. But when I put 240-pound A up front with me, the CG plot points were outside the envelope. That means that I might not have enough aft cyclic to arrest forward motion. In other words, I might not be able to stop. So I recalculated with the big guy in the back. The plot points slipped back inside the envelope. Problem solved.

So I recalculated with the big guy in the back. The plot points slipped back inside the envelope. Problem solved. It was a beautiful morning — cool with calm winds. I’m based at an ag strip and I was very surprised that the pilot wasn’t flying. After all, the sun had been up for over an hour and the conditions don’t get any better for spraying crops.

It was a beautiful morning — cool with calm winds. I’m based at an ag strip and I was very surprised that the pilot wasn’t flying. After all, the sun had been up for over an hour and the conditions don’t get any better for spraying crops.

The sky was intensely dark out toward the river and the storm was definitely heading in my direction. But what was even scarier was the low hanging cloud near me that seemed to be swirling gently like something from a Weather Channel tornado special. I watched it for a while, wondering whether the storm was really intense enough to get a tornado going. It didn’t seem to be.

The sky was intensely dark out toward the river and the storm was definitely heading in my direction. But what was even scarier was the low hanging cloud near me that seemed to be swirling gently like something from a Weather Channel tornado special. I watched it for a while, wondering whether the storm was really intense enough to get a tornado going. It didn’t seem to be. I came in over the orchard in a grand, swooping arc, settling in at the southeast corner in a hover over trees nearly as old as I am.

I came in over the orchard in a grand, swooping arc, settling in at the southeast corner in a hover over trees nearly as old as I am.

Today, I got an email message from UPS Quantum View

Today, I got an email message from UPS Quantum View