How about preventing accidents by making conditions easier for new pilots?

I stumbled across this brief preliminary accident report in the NTSB database today. Here it is in its entirety:

The pilot who held a commercial pilot certificate with single-engine land airplane ratings was receiving training to obtain a helicopter rating. The pilot had 31 hours of helicopter flight time and the accident occurred on his second solo flight. The pilot reported he was attempting to takeoff from a wet grass area when the accident occurred. He stated that when he increased the collective to lift off, the helicopter began to roll to the right with the right skid still on the ground. He moved the cyclic to the left and the helicopter responded by rolling to the left with the left skid contacting the ground. The pilot then applied right cyclic and the helicopter again rolled to the right. The right skid contacted the ground and the helicopter rolled over onto it’s right side. As a result of the accident, the main rotor blades and the helicopter fuselage were substantially damaged. The pilot reported that there were no preimpact mechanical failures/malfunctions that would have precluded normal operation.

The accident aircraft was a 2003 Robinson R44 Raven II.

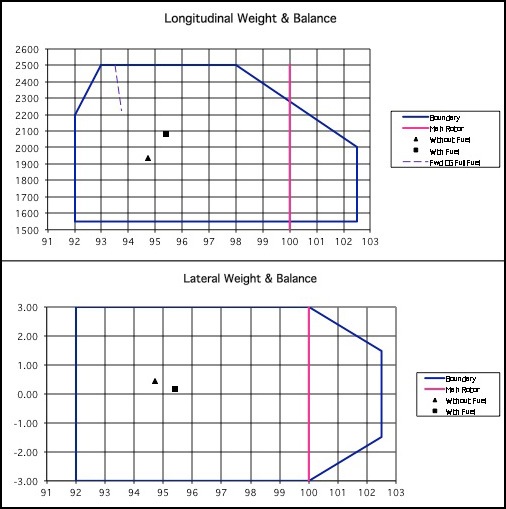

Those of us who have soloed in Robinson (or other small) helicopters know that balance varies greatly depending on how many people are on board. We learn to fly helicopters with two people on board: student pilot and instructor. The helicopter is usually quite balanced with two people on board. I don’t have the exact numbers for this particular flight, but using my R44 as a guide and assuming the pilot and instructor were each 200 pounds with 1/2 tanks of fuel, the weight and balance envelopes should look something like this:

If you’ve never seen one of these, let me explain. The longitudinal weight and balance chart shows where the weight is distributed front to back. The pink line represents the main rotor mast. With two 200-pound people on board in the front seat, the center of gravity is forward of the mast. This is pretty normal for an R44. The lateral weight and balance chart, which is what we’re more concerned with in this analysis, shows how the weight is distributed side to side. The 0.00 mark is dead center and, as you can see, the with/without fuel points are very close to the center. In other words, it’s laterally quite balanced.

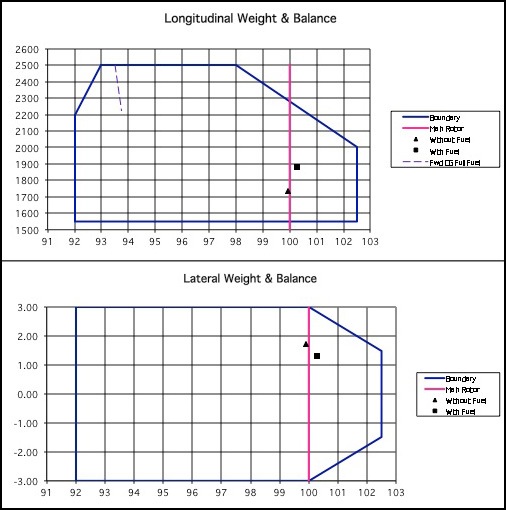

Now take the instructor out of the left seat. With everything else remaining equal, here’s what the weight and balance envelopes look like:

First of all, the center of gravity shifts aft. That makes a lot of sense. After all, there’s 200 pounds less weight up front. When I fly, this is extremely noticeable, especially at my new, slimmer weight. The helicopter actually lands on the rear of its skids first; on pick up, the front of the skids come off the ground first.

Laterally, there’s also a big change — and again, that’s what we need to focus on here. Without that 200 pounds of weight on the left side of the aircraft, the center of gravity shifts quite a bit to the right. The heavier the pilot is, the more to the right the weight shifts. So although I used 200 pounds in my example, if the pilot was 250 pounds — which is still legal in an R44 — the weight would shift even further to the right (and slightly forward). When the pilot attempted to lift off, the left skid would rise first.

Again, I don’t have the exact numbers. You can play with this using any reasonable numbers you want. It won’t change the conclusion here.

Now read the description of the accident events and put yourself into the pilot’s seat. He’s taking off so he’s lifting the collective slowly, getting the helicopter light on its skids. The left skid comes off the ground first because that side of the aircraft is lighter. This feels to the pilot as if the helicopter is rolling to the right while the right skid is still on the ground.

Stop right there. This is where the terrain comes into the picture.

The pilot is on wet grass. The accident report didn’t say mud so we won’t assume a sticky surface. But it certainly isn’t smooth. We don’t know how long the grass is or whether it’s uniform or has clumps of thick weeds. The question we should be asking is this: was the right skid “stuck” and creating a pivot point? The answer to that question determines the appropriate action:

- If the right skid is indeed “stuck” and creating a pivot point, the correct action to avoid dynamic rollover would be to lower the collective. In other words, abort the pick up.

- If the right skid was not “stuck” or creating a pivot point, the correct action would be to adjust the cyclic to assure there was no lateral movement (as you’d normally do in a pick up) and continue raising the collective.

An experienced pilot would know this. An experienced pilot would have done dozens or hundreds or thousands of solo pickups. He’d have a feel for the aircraft or, at least an idea of what to expect and what to do.

But this wasn’t an experienced pilot. It was a student pilot with only 31 hours of flight time — almost all of which was with a flight instructor beside him — on his second solo flight. So he used the cyclic to stop what he perceived as a roll. He may have been more aggressive than he needed to be, thus causing the helicopter to come down on the left skid. Then another adjustment to the right. The right skid hits that grassy surface and the helicopter rolls. Game over.

So my question is: What the hell was he doing taking off and landing on wet grass?

Flight instructors can reduce the chances of accidents like this by setting up their student pilot solo flights with easy flight conditions. That includes smooth surfaces for takeoff and landing. If this had happened on a nicely paved airport ramp or helipad that was free of surface obstructions like cracks or tie-downs, this accident may not have happened at all. There would be no question about a pivot point because none could exist.

You might also question whether the flight instructor properly taught the concept of dynamic rollover and what to do if it’s suspected on takeoff — lower the collective. And whether the flight instructor made it clear that there should be no lateral movement on pick up or set down. Yes, I know that’s hard for a new pilot to do — especially with only 31 hours — but it’s vitally important, especially on surfaces that could snag a skid.

Which brings me back to my original point: why was he taking off from wet grass?

Fortunately, the pilot was not injured, although the helicopter was substantially damaged. I think this accident makes a good example for teaching about dynamic rollover. With luck, instructors and students will learn from the mistakes here and avoid them in their own training experiences.

Of course, another possibility is the the student pilot simply was not ready to solo.

It was a real shop-till-you-drop experience. I bought 9 long-sleeved t-shirts, 2 short-sleeved t-shirts, 2 lace camisoles, 3 tank tops, 3 sweaters, 2 pairs of Levis blue jeans, and a belt. I also bought 2 pairs of shoes — one of which I put on in the store and threw away what I’d been wearing. The sales made all this possible. With sale prices and two coupons, I spent less than $350 and got quality merchandise from stores like Eddie Bauer, Bass Shoes, Levis, and Tommy Hilfiger.

It was a real shop-till-you-drop experience. I bought 9 long-sleeved t-shirts, 2 short-sleeved t-shirts, 2 lace camisoles, 3 tank tops, 3 sweaters, 2 pairs of Levis blue jeans, and a belt. I also bought 2 pairs of shoes — one of which I put on in the store and threw away what I’d been wearing. The sales made all this possible. With sale prices and two coupons, I spent less than $350 and got quality merchandise from stores like Eddie Bauer, Bass Shoes, Levis, and Tommy Hilfiger.