About 950 nautical miles in one day.

I flew commercial down to Arizona on April 11 to pick up my new old helicopter, N7534D. If you missed my blog post about my purchase process and what went into the decision to buy this helicopter, you can find it here. This blog post pretty much picks up where that one left off.

Flying South

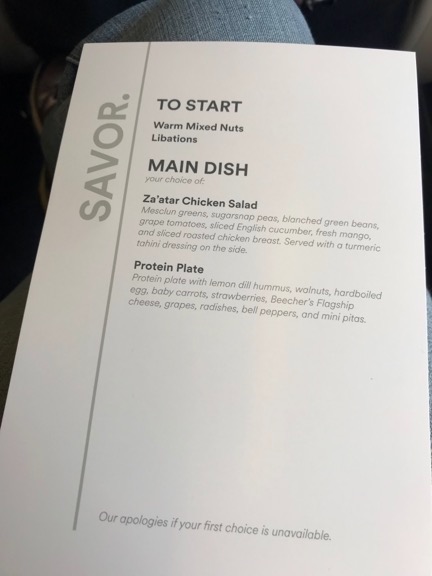

I treated myself to a first class ticket, which I sometimes do when I’ve got a job ahead of me that might or might not be difficult. And instead of departing Wenatchee on the 5:55 AM flight, which, via a connection through Seattle, gets into Phoenix at 10:43 AM, I took the 11:35 AM flight with a connection at 1:42 to arrive in Phoenix at 4:30. Unfortunately, weather moved into Seattle that morning and they delayed our flight from leaving Wenatchee. For a short time, it looked like I’d miss my connection. But Alaska Air had my back (at least this time). Not only did they automatically add a booking on the next flight to Phoenix, but they made sure they gave me a first class seat there, too. So even if I missed my flight, I’d travel in the comfort I paid for.

I had the salad. It was good. And have I ever mentioned how much I enjoy flying First Class? (Another perk of the single lifestyle; only one plane ticket to buy means airline travel is more affordable.)

But I didn’t miss the connection. I was the third to last person on board. I felt bad for Penny since I didn’t let her out of her bag — as I usually do — when hurrying across the airport to make the connection. She settled under the seat in front of me, still in her bag, on the Seattle to Phoenix flight while I settled in to a spacious and comfy seat and accepted the lunch menu the flight attendant handed me.

I enjoy flying First Class on Alaska Air. (Not so much with other airlines.) The food is always good and they have an excellent Bloody Mary mix. The seats are very comfortable. And I’ve discovered that the best way to make a long flight shorter — no matter where you’re sitting — is to watch a movie on a tablet. This time, I watched Coco, which I highly recommend.

Some Lurking Stress

Watching the movie also got my mind off the stress of my upcoming meeting with a new helicopter. There were a few things feeding it.

First, I hadn’t flown since my accident back on February 24. That was about six weeks. I’ve gone a lot longer between flights — heck, I went from December 4, 2017 to February 15, 2018 (ten weeks) and October 30, 2016 to February 22, 2017 (nearly four months) — but this was different. It was the elephant in the room — my crash — and the uneasiness was growing on me every day.

Logically, this didn’t make sense. I knew what caused the crash and I could easily prevent it from happening again. I had no uncertainty about my skills or the aircraft. But I think the people who were encouraging me to “get back in the saddle” were starting to make me wonder why they thought I wouldn’t. Maybe I was missing something?

This nagging concern got to a head about a week before I was supposed to pick up the helicopter. I actually asked Paul, the Director of Maintenance at Quantum who was handling the sale, to schedule a flight instructor to fly with me for about an hour before I left with the ship. Why not get a little refresher?

The other stress had to do with my route home and the weather. I’d been thinking a lot about my route for the flight and even blogged about the pros and cons of each option. I was very motivated to minimize flight time, but I was not interested in crossing the vast emptiness of central Nevada, which was the shortest route. And then there was a perceived need to go through California to pick up my old cockpit cover and floor mats, which were still in the custody of the aircraft salvage guy.

The trouble was, the forecast was calling for crazy high winds on Thursday and Friday. A front was coming through on the night of my arrival and the forecast was showing winds as high as 40 miles per hour. Although I tried to change my schedule to come in early on Wednesday for departure the same day, hoping to beat the winds out of the area, it was pretty clear that I would hit those high winds somewhere on my route . Besides, the helicopter wouldn’t be ready. The earliest I could pick it up would be Thursday, right when those high winds were scheduled to really ramp up.

Normally, a day or two delay wouldn’t matter. After all, I was staying with some friends in Gilbert, AZ and it was always nice to hang out with them. But on this trip, I’d be accompanied by my good friend Janet, who would then stay a day or two with me in Washington before flying back to Phoenix on Alaska Air. Her 5:55 AM Tuesday ticket could not be changed and I was really hoping to have her as a guest for more than just a day. In addition to that, I had some freshly hatched chicks in the brooder of my chicken coop and didn’t like the idea of leaving them for longer than absolutely necessary. Leaving Phoenix on Saturday would probably mean getting home by Sunday. And there was unsettled weather forecasted for northern Oregon and Washington on Sunday that could delay us further.

So the long flight home and weather-related delays were stressing me out, too.

And then there was the added stress of flying a helicopter that wasn’t mine. How would it fly? What would it sound like? I knew every quirk in the late, great Zero-Mike-Lima but didn’t know this one at all. (And yes, every aircraft has quirks.) That was made a little worse by a friend suggesting that there might be issues with the “rigging” (WTF?) and that I should fly it around locally before leaving the area in case anything needed to be fixed. More delays?

I kept telling myself that with Paul in charge of maintenance and the aircraft always being owned by Quantum, there wouldn’t be any mechanical issues. There was no way Paul would let an aircraft go that wasn’t perfectly safe and functional. That’s why I’d bought this helicopter instead of one of the other options — it came with peace of mind. Quirks were quirks and I’d figure them out over time.

Still, all these little things were accumulating in my brain, giving me more stress than I really should have had. Fortunately, I was able to switch off that stress on the flight to Phoenix and for the rest of the evening, which I spent with my friends.

The Pickup

The forecast was right. The wind kicked in on Thursday morning. I still had hopes of picking up the helicopter and getting it to Wickenburg — which is where I’d be meeting Janet — before things got too rough, but Paul texted to say that they’d found a small problem with the radios and the avionics guys still had to do their inspections. So I waited at Falcon Field, the Mesa airport where my friends have a flight school, watching the flag I could see through the window. The wind got rougher. They started cancelling their flights.

We went out for Thai food for lunch. Then back to Falcon Field. The helicopter was ready, but I probably couldn’t fly away. Still, I had paperwork to do and there were a few things I could do to prep the helicopter for its departure. My friends gave me their car keys. I loaded Penny up and we drove to Chandler.

The wind was very bad there. And because Chandler is close to the edge of the desert, the blowing wind had kicked up a lot of dust. Visibility was down to about a mile: IMC (Instrument Meteorological Conditions). No one was flying. Quantum’s door was locked with a sign to knock. When the girl at the desk came to open it for me, she explained that the wind and air pressure made the door swing open if it wasn’t latched.

I saw Paul and Doug and Neil, all of whom I’ve known since my primary flight training days in the late 1990s. We did the socializing thing. Then Paul brought me out to see the helicopter I’d come to buy. It was optimistically hooked up to the tow cart, parked right in the middle of the hangar.

N7534D was waiting for me when I arrived. And I don’t know why, but almost every photo I take with my iPhone makes the helicopter look black. It isn’t. It’s actually a dark blue with a flat black stripe. Also parked in the hangar: at least three R22s that I’d flown during my flight training in 1998 through 2000; two of them have over 20,000 hours!

I went over for a good look. When I opened the pilot door and looked at the interior all worries about it not being my helicopter were washed away. It was virtually identical to Zero-Mike-Lima, from the tan carpeting and leather seats to the layout of the instrument panel. The only difference I saw — and didn’t even notice until I was nearly home — is that the Hobbs meter and clock are switched on the instrument panel. Paul had even installed the bar across the footwell on the pilot’s seat where I’d use RAM mounts to install my phone and iPad.

There were differences, of course. The gyros, which switched on automatically when Paul turned on the master switch, were louder. The glass on a few of the instruments looked a little hazy. There were tiny bits of damage on the pilot seat, almost like cigarette burns. Just enough to remind me that it wasn’t Zero-Mike-Lima. But it was close enough that any worries I’d had about flying again immediately went away. Of course I could fly this.

Penny wanted to sit in the helicopter so I put her in there. Note that I’ve already got my hat hung on the cyclic. Home sweet home?

I put Penny in the front passenger seat, where she really wanted to sit, and did a walk-around with Paul. He answered any questions I had. Then I took the canvas bag I’d brought with two headsets and my RAM mounts and began setting up the cockpit for my flight. It was a real relief to see that the helicopter had been hardwired for Bose headsets, since the ones I use in the front two seats are Bose without battery packs.

Meanwhile, Paul gathered up the paperwork and other things that came with the helicopter. This included a brand new, still in its original packaging, full cockpit cover, blade tie-towns, and ground handling wheels. (All of a sudden, I had no pressing need to fly though California on my way home.) I stowed all of it under the rear seats so I’d have plenty of room for luggage on top of the seats.

Sometime while all this was happening, I handed over the big certified check I’d picked up from the bank the day before. The purchase price did not include the cost of the USB ports Paul had put on that bar to keep my iPad and phone charged in flight and a few other things, so I fully expected to pay a bit more. But I did have money on account with Quantum for Zero-Mike-Lima’s core returns during overhaul the year before. So they cut me a new check for $700+, which I actually forgot about until I found it just yesterday.

Back in the office, I filled out forms and signed papers. I chatted with Paul and Doug and Neil. I looked out the door and saw the thick blowing dust. I knew damn well I wouldn’t be flying to Wickenburg that afternoon. I told them I’d be back in the morning, probably around 7:30 AM. Although the wind was supposed to pick up again, I was hoping I could get it out of the Phoenix area before that happened.

Then I hopped back into my friend’s car and went back to Falcon Field, stopping for a DQ hot fudge sundae along the way.

Chandler to Wickenburg

I spent a second night with my friends in Gilbert. We went to the Monastery, a local pilot hangout, for drinks after work, when back to their house for leftover Chinese food. It was nice to relax. I felt good about my upcoming trip, although I still didn’t know when I’d be able to head out beyond Wickenburg and which route I’d take. Heck, I wasn’t even sure I’d be able to leave Chandler.

But in the morning, the wind was relatively calm and the sky was clear. I had coffee with my friends, turned down their offer for a ride to Chandler Municipal because I didn’t want to wait or have them drive so far out of their way on the way to work, and caught a ride with Lyft instead. I was at Quantum’s unlocked door at 8 AM.

Doug came in just as I was heading to the hangar with my wheelie bag with Penny in trail. But the helicopter was gone. One of the guys in the hangar told me they’d put it outside for me. The big hangar door was closed. I went through a man door to the ramp. N7534D was parked right there on one of the pads.

It almost looks blue in this photo. I should mention here that the N-number is painted on in the same black as the stripe. Can you see the stripe? Well, the painted N-number is just as visible. Because the FAA would definitely balk at that, Paul used decals cover them with the same numbers in white.

To my surprise, Penny ran right over to it. Well, why shouldn’t she? It was ours, after all.

I was pleasantly surprised to find a small pile of Quantum swag on the front passenger seat, including a slick-looking jacket, two tee shirts (one long sleeve and the other short sleeve), and two baseball caps. I put on the jacket — it was cold that morning! — and stowed the other things in my suitcase.

I put Penny inside on the front seat on the small dog bed I’d brought along for her. (She doesn’t like sitting on leather.) Then I loaded up the luggage and did a preflight. The oil dipstick, which is shorter than the one in Zero-Mike-Lima was, showed just under 7 quarts of very clean oil. Robinson are funny about oil. The manual says 9 quarts, but if you put in more than 7, it usually just blows it out when the engine is running. I kept Zero-Mike-Lima’s right at 7. I figured I’d check this one again when I got to Wickenburg to see if it got lower. But I did go back into the hangar and ask Doug if I could buy some oil. He gave me two quarts of W100Plus; according to the log book I had on board, that’s what Paul’s team had put in it. (It’s also what I’ve always used.)

By this time, the wind was about 12-15 miles per hour out of the northwest — just the direction I had to go. Out on the edges of the ramp, two or three R22s were practicing hovering right into the wind. It was blowing right up my helicopter’s tail. That meant my first pickup in this ship would be with a nice little tailwind. Nothing like getting back into the saddle — on an unbroke horse.

I got my iPad EFB all set up with my flight plan filed. Then I started it up. It caught on the second try; I knew it would be a while before I learned exactly how much priming I’d need in different conditions. The engine sounded different. The blades spun up silently — no squealing drive belts! The idle was low. When the needles matched, I had to add throttle to keep it at 55% RPM until the clutch light went out.

My mind noted all of these things automatically. It was different from Zero-Mike-Lima, but not wildly different. I listened to Chandler’s ATIS on the GPS radio while the engine warmed up. Although I felt as if I should be in a hurry, I reminded myself repeatedly that I was not. I dialed in both of Chandler’s tower frequencies on the main radio in case I needed to switch when I crossed the runway. I listened to the tower frequency; there was just one plane on the radio and he landed before I was ready to take off.

I brought the RPM up to 100% and carefully lifted the collective, mindful of that strong tailwind. My feet were firm on the pedals, prepared for the dance I might have to do. But if there was any dancing, it was instinctive. I picked it up off the ground smoothly with virtually no yaw or wiggle. I gave it some right pedal and turned around smoothly, pointing it into the wind.

Just like riding a bike.

I called the tower and asked for departure to the north. He asked if I wanted departure from present position or from the helipad. I told him I preferred present position; I really saw no reason to waste time or fuel hover taxing over to the pad. He gave me the usual “departure is at your own risk” disclaimer and cleared me northbound over both runways. Somewhere during our exchange, I used the wrong N-number and quickly corrected myself, adding “new helicopter.” Then I was airborne above and between the two light posts on the north edge of the helicopter parking area, climbing away from Quantum.

I took one of my “usual” routes to Wickenburg — north just outside of the Phoenix surface airspace, then west along Camelback Road, then northwest direct to Wickenburg. I hit some moderate turbulence between Camelback Mountain and North Mountain that were likely caused by wind over the mountains north of me, but that cleared up by the time I passed Piestewa (formerly Squaw) Peak. There was a little more turbulence along the way. Otherwise, it was a pretty uneventful flight. I skirted around the special Luke Air Force base surface training area southeast of Wickenburg so I wouldn’t have to talk to Luke Approach. The flight path was familiar — I’d flown it at least a hundred times when I lived and flew regularly in Arizona.

My route from Chandler (CHD) to Wickenburg (E25) on Friday morning.

When I got within radio range of Wickenburg, I flipped on the AWOS on my second radio. Winds were 15 gusting to 23. Whatever. I flew over my old house — which I have to say looks a hell of a lot better than when I lived there with my wasband — but didn’t see any sign of Jeff or Mary, who now live there. I came in over the golf course and made a short right base to the taxiway parallel to Runway 23.

I set down temporarily near the taxiway as my friend (and insurance agent) Dave towed his helicopter past on a cart for departure from the helipads on the far west end of the ramp. Then I hover-taxied over to one of the two fuel trucks parked near the big fuel tanks adjacent to the parking area and shut down. I caught Dave on the radio just as he was taking off. “I thought the new helicopter was red,” he said as he made his departure toward Scottsdale.

I’d hear that a lot over the next few days, and likely in weeks to come.

Overnight at Wickenburg

I got fuel and although I’m tempted to tell you the saga of the Town of Wickenburg’s stupidity at installing a costly fuel system that won’t work property, I won’t waste your time or mine. Short version is, fuel came from a truck that can’t move and when fueling was done, I was told I couldn’t keep the helicopter parked there overnight, despite the fact that I’d purposely parked it out of the way. Okay. I wasn’t sure if I’d be spending the night anyway. I was told I could park there until noon; if I needed to stay longer, I’d have to move it. Fair enough.

The good news is, the fuel was only $3.95/gallon. They’re trying to empty the tanks so they can get them fixed in June. The bad news is, it was a short flight so I didn’t need much fuel to top off both tanks.

I called my friend Janet to come get me, then locked up the helicopter. That’s when I discovered that the front passenger door wasn’t seated quite right. I suspect that whoever put the swag into the helicopter that morning had let the door get caught by that tailwind. It would need some work with a screwdriver and pair of pliers to fix it. I also discovered that that door lock was kind of funky; normally you turn the key 1/4 turn to lock it but this one has to turn 1/2 way around.

Remember what I said about quirks? I was learning them.

I went to a late breakfast with Janet in town. While there, I checked the weather. No matter which way we went, we’d hit high winds that day. So after breakfast and a few errands, we stopped at the airport so I could reposition the helicopter on a far east ramp that hadn’t existed when I was based at Wickenburg. We used the brand new blade tie-downs and the tailgate of her truck to secure the blades against the wind. Then we headed out to the off-the-grid ranch she and her spouse, Steve, and their animals were living at.

The wind howled all day, making it very unpleasant outside. We chatted in the living room of the fifth wheel they now live in full time. I made a piece of jewelry. She read. We met with Steve when he returned from riding drag on a horseback ride for four city slickers. Janet cooked the pizza we’d picked up at the supermarket.

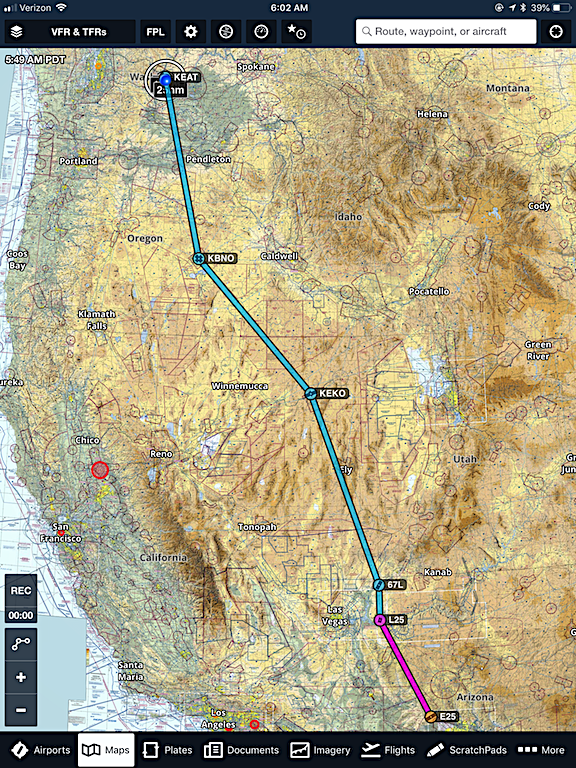

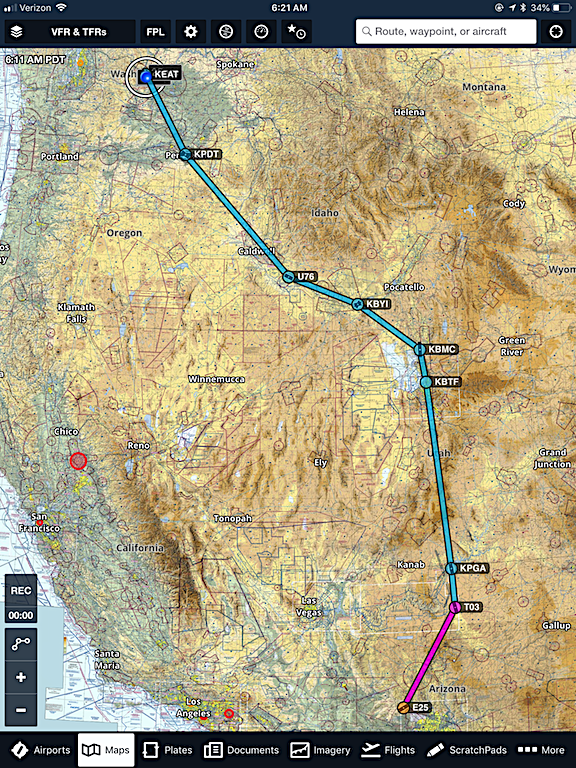

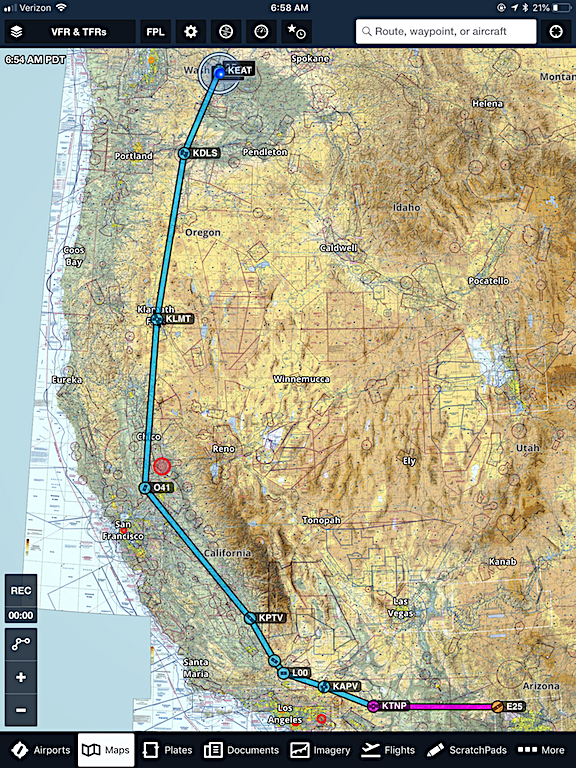

Meanwhile, I kept checking the weather — I had a barely acceptable connection on my iPad that switched from 3G to LTE — and thinking about routes. We planned to depart by 8 AM the following morning. I was starting to lean toward the one route I hadn’t completely done before: the western Nevada route. The weather looked doable, but I didn’t like the forecast nearer to home for Sunday. I’d want to get as far north as possible before stopping for the night.

I left them to spend the night in the little travel trailer they’d bought for small trips Janet often needs to make throughout the year. I had the whole place to myself and slept like the dead.

The Long Flight

I was already awake when the generator went on just before 6 AM. I immediately plugged in my iPad, then went out in search of coffee.

By this time, I had pretty much decided on the western Nevada route, which would save at least 2 hours over the California route. Time is money, especially when flying a helicopter.

Both Janet and I were ready to go at 6:30, so rather than sit around and waste time, we loaded up the truck and let Steve take us to the airport.

Using the truck tailgate again — I really do need to get my collapsible stool on board — we pulled off the blade tie-downs. I did a preflight and added a quart of oil, kind of surprised to see that there was absolutely no sign of dripping under the ship. (Most Robinsons let a few drops of oil go from the drain port when parked; this was a quirk I could certainly live with.) Then we loaded up all the luggage, moved Penny’s bed to the back passenger side seat, and prepped to go. Steve watched us start up and take off.

I flew over my friend Jim’s house but saw no sign of life.

Then we were on course northwest bound, heading 301° toward our first fuel stop in Pahrump, 209nm away. We were originally supposed to stop at Jean for fuel — that’s just southwest of Las Vegas on I-15 — but unlike too many other pilots, I did read the NOTAMs, which informed me that there was no fuel at Jean until June. (I didn’t believe the NOTAM, so I called the phone number and got connected with someone at Henderson Executive Airport who confirmed there was no fuel.) Seriously, pilots: read the NOTAMs. (There’s also this old blog post about an idiot pilot who didn’t read the NOTAMs and unsuspectingly flew into a busy airport hosting an EAA Young Eagles event.)

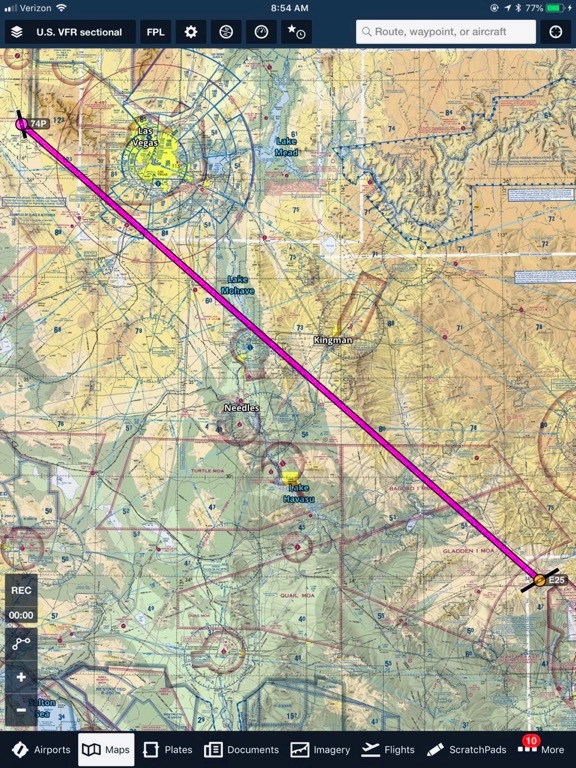

Our route from Wickenburg (E25) to Pahrump (74P) cut through miles of empty Arizona and Nevada desert, crossing the Colorado River at the south end of Lake Mohave.

Our flight path put us just east of Route 93 to the west of Alamo Lake. And that’s the only place we hit turbulence — a pretty good roller coaster ride as we passed near some hills about 10 minutes out of Wickenburg. My first thought was: this better not be an all-day thing. Janet later told me that it bothered her a lot more than she let on. I suspect that’s because after many years of flying with passengers in all kind of conditions, I’m very careful to never look annoyed or scared in turbulence or other weather-related conditions. Passengers take their cue from the pilot; if the pilot doesn’t look bothered, there’s obviously nothing to worry about.

There were pilots landing at the dirt strip out at the Wayside Inn south of Lake Alamo. I didn’t see them, but I heard them on the radio. Weekend pilots, meeting up for breakfast. I wished, in a way, that we could stop and join them.

We passed the old grid of lots in the big, broad valley east of Crossman Peak (east of Lake Havasu). It’s flat and sparsely populated and I can bet it was full of blowing dust the day before. I’d been over the area before and was always amazed that people would buy land all the way out there. It had to be 10 to 20 miles or more on graded dirt roads to get to any pavement in any direction. And even then, where was the closest town with a supermarket and other services? Needles, NV? Kingman, AZ? People think I’m crazy living 10 miles from the nearest supermarket but that’s only because they haven’t seen these middle of nowhere homes. It’s all relative.

I talked briefly to Bullhead City’s tower, telling them I wanted to transition on the east edge of their space northwest bound. Then we crossed the Colorado River just upstream from the Davis Dam, at the south end of Lake Mohave. We had entered Nevada.

We crossed a few more mountains and I climbed to avoid the possibility of mechanical turbulence. It also gave me a chance to play with my radio altimeter (which I never wanted). As I consulted it periodically through the trip, I soon learned that it lagged in its readout of altitude changes and would be, as I suspected, completely useless in my operation. I’m sure the manufacturer of the device is still patting itself on the back for successfully lobbying the FAA to require them. How much additional revenue have they managed to squeeze out of VFR pilots who don’t need such a device for safe operation?

We passed to the east of Searchlight, NV; I saw it’s huge American flag fluttering in the breeze.

Janet pointed out the big solar farms in California near Primm. I remembered driving past those on I-15 just a few weeks before. They use mirrors to focus sunlight on a tower that heats oil (I think) to run a turbine and generate electricity. As the VFR sectional chart for the area warns, there’s the possibility of “ocular glare” from the tower which glows brightly in the desert.

We passed over the top of Jean and kept going. We could see Las Vegas off in the distance. Then we were flying up the valley west of the Spring Mountains and Mount Charleston, over Pahrump for landing at Calvada Meadows (74P).

Of course, just before landing, there was a guy on the radio who reported in at about the same position we were. I tried to get him to provide his altitude or other information that would help me spot him, but he had a heavy accent and I think he was having trouble understanding me. I kept slowing down and flying lower and lower; helicopter pilots know that airplanes generally don’t fly below 500 feet AGL. Finally, I was abeam the airport and needed to fly across the runway. I looked both ways and darted across. It wasn’t until we’d taxied up to the weird little fuel ramp that Janet pointed out a powered hang-glider — is that what you call those things? — about a mile from the airport. I don’t know where he landed, but it wasn’t near us.

Here’s Janet, sitting in the front passenger seat at Pahrump. Okay, so it looks blue here. Kind of.

I let Penny out and fueled up while Janet used the restroom, which was an ancient looking port-a-potty. She said it was pretty gross. I had to go so I wound up using it. I’d been in a lot worse ones than that.

A small twin came in and pulled up behind me on the one-lane ramp. A car came out to meet him. By the time I’d checked the oil — which seemed low but was hard to read because it was so darn clean — and was ready to go, he was parked on the dirt beside the ramp. There are tie-downs there and I hadn’t even seen them.

We took off and continued northwest, now heading 307°. Our next planned fuel stop was Hawthorne, NV, only 186nm away. I had originally been worried about making this leg from Jean, but when we switched to Pahrump, the distance got shorter. We probably could have stretched the leg out to Silver Springs. But I had already told my friend Jim to let our mutual friend Betty at Hawthorne know that we were coming. So with Betty expecting us, I had to stop there.

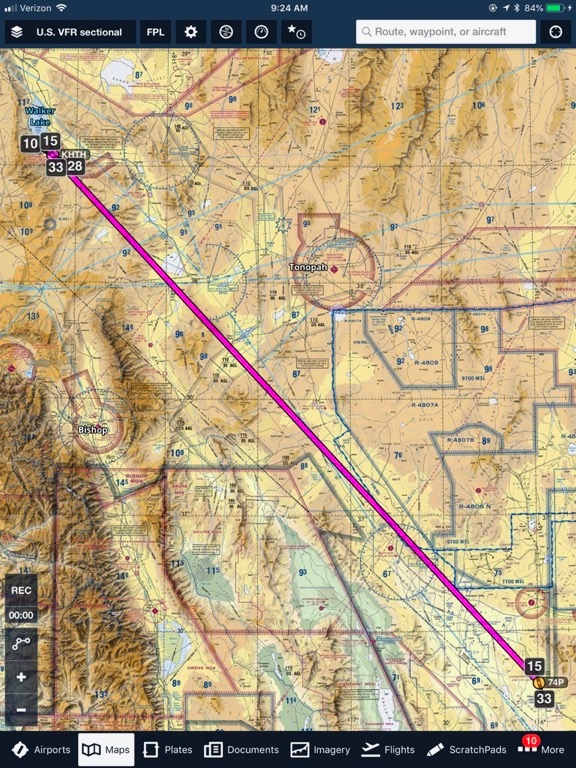

Our route from Pahrump (74P) to Hawthorne (HTH), NV took us over some pretty barren desert.

The stretch between Pahrump and Hawthorne was pretty remote and kind of dull, especially when you’ve already spent hundreds of flight hours low-level over southwestern desert. The only highlight I can think of was near Beatty, NV, when I drifted off course and Janet caught sight of the old ghost town of Rhyolite. I’d been there on the ground twice and this time I dropped down to fly over it so Janet could have a look. Then we climbed out of the dead end valley, over some hills, and into the area known as the Sarcobatus Flat, just west of route 95.

The terrain was typical desert with a mixture of rocky outcroppings, eroded hillsides, dry lake beds, and sand dunes. There were few roads and even fewer paved roads. We caught sight of another Solar Farm off in the distance to the east. We skirted around mountains rather than going over the tops of them. My GPS showed a tailwind that ranged from 5 to 20 knots. There was no turbulence.

It wasn’t long before we were descending over the hills and old munitions storage areas to the town of Hawthorne, with Walker Lake beyond it. Although I’d driven through Hawthorne at least twice — most recently in late 2016 — I’d never flown in and had trouble finding the airport. But then I saw it and with almost no wind came in for landing on the ramp near the very large and impressive fuel island. Betty, who had heard my radio calls, was waiting in a golf cart to greet us. It was about 11:30 AM.

If you’ve never stopped at Hawthorne, it’s worth it just to meet Betty. I don’t know how old she is, but she’s probably got at least 15 years on me. She’s tiny and she knows everything about the airport and most of the aircraft that come and go. My friend Jim, who used to fly for Continental (and then United) met her on a cross-country trip in a general aviation aircraft with a friend and became friends with her. He used to talk to her from 30,000 feet when he overflew the area in a jet. (Ever wonder how pilots kill time in the cockpit on those commercial flights?) She’s not an airport employee — she’s a volunteer — but she’s worth her weight in gold and is more enthusiastic and helpful than just about any airport employee I’ve ever met.

After helping me figure out the quirks in the fuel system and chatting with us as I fueled, she drove us over to the FBO building and handed over the keys to the courtesy car. We drove over to McDonalds to grab a quick lunch from the drive up window and brought it back to the airport to eat. Betty kept us company, telling us about her new Doberman puppy. Then, after an hour had gone by, I reminded everyone that we had more distance to cover before nightfall.

Betty drove us back to the helicopter. I checked the oil and it looked the same. We loaded up and took off. Betty took pictures of our departure, which I fully expect to see in the newsletter she publishes every week.

Here’s N7534D, still not looking very blue, at Hawthorne. It was a gorgeous day there.

The next leg was from Hawthorne to someplace called Lakeview, on Goose Lake, just over the Oregon border on a heading of 326° for 231nm. We didn’t fly it exactly as planned. Instead, we went up the east side of Walker Lake and the west side of Pyramid Lake. (I really don’t like flying long distances over open water.) By the time we got near the Oregon border, we’d drifted so far west of our plotted course that we wound up west of Eagle Peak and the South Warner Wilderness area, which turned out to be a good thing.

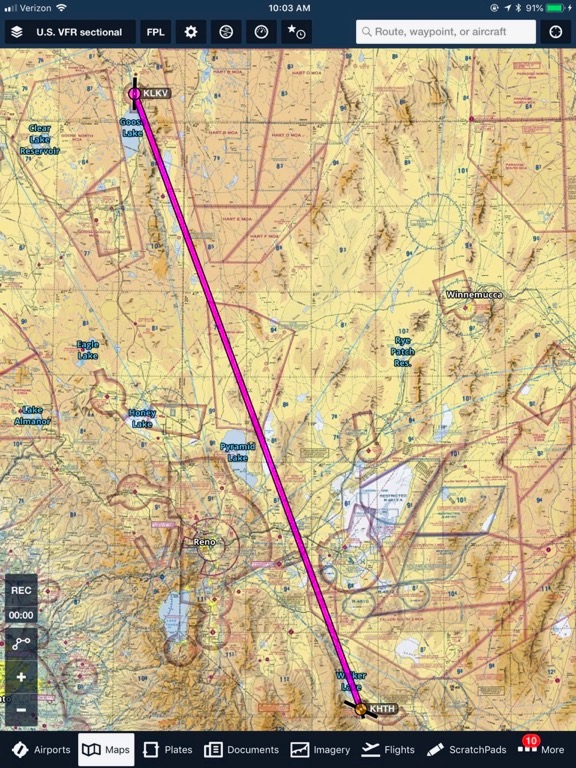

Here’s our plotted course from Hawthorne (HTH) to Lakeview (LKV). We wound up flying mostly a little west of this course.

Of all the legs of this journey, I think this was the most interesting — at least to me. I really enjoyed flying up the two lakeshores, especially up Pyramid Lake, which I’d never flown or driven by before. (My only Pyramid Lake experience was on my so-called “midlife crisis road trip” back in 2005, but I’d drive up the valley to the east of there, up the longest dry lake bed I’d ever driven along.) Looking down at the folks camping and fishing along the shore — especially near the town of Sutcliffe — I really wished I could just drive up with my truck camper and boat and join them.

After Pyramid Lake, the scenery got kind of dull and then interesting and then dull again. It’s the monotony of the desert terrain. Just when it starts to get boring, all of a sudden you notice a change and then it’s interesting again. In this area, it was most mostly weird colors and erosion patterns in the desert that caught our eyes.

And then, in the northeastern corner of California, just west of the South Warner Wilderness area, I caught sight of the first herd of wild horses. I pointed them out to Janet, who didn’t see them right away, and then lowered the collective, pulled back on the cyclic, and started a descending left turn to go back to them, putting them on Janet’s side. Thinking back on that moment now, the entire maneuver — which was far beyond the straight and level flying I’d mostly been doing all day — was done without a moment of thought. Heck, why not? How many times had I done the same thing in Zero-Mike-Lima? This helicopter responded exactly the same way and I didn’t give anything a second thought. I wanted to slow down, swing around, and descend for a closer look and my hands and feet did what needed to be done to make that happen.

Janet saw the horses and then another bunch and another. Soon we realized that the entire desert was covered with small herds of horses. Janet figures at least 50 horses, but I think there had to be over a hundred in the multiple groups I spotted from the air. I got back on course, feeling happy about it. After all, who doesn’t like seeing wild horses in the middle of nowhere from the air?

We passed to the east of Alturas, CA, and flew up the east shore of Goose Lake. The wind had picked up a bit but it was still a tailwind. We were making good time. I approached the airport, making all my radio calls, and came in from the west, landing into the wind in front of the fuel island.

The place was nearly deserted. There was a big hangar with its door open and a guy working inside on the shell of an old Huey helicopter. A partially disassembled R44 was parked beside it. Later, when I went in for a chat, I’d see that the R44 had bright red leather seats in perfect condition.

I fueled while Janet and Penny stretched their legs. Janet had been having some back pain and really needed to move around. I added that second quart of oil. I went to chat with the guy in the hangar — I really can’t remember why. I might have been looking for Penny. Then, with nothing much else to do, we loaded up and headed out.

The next leg was also short and it was supposed to be the last for the day: Lakeview to Madras, OR. I had already called ahead and discovered they had a courtesy car we could use overnight. I figured we’d fuel up, park, and drive into town for dinner and a motel room.

But it was still early in the day and sunset at home wasn’t expected until 7:50 PM. I wasn’t sure how long the leg from Madras to Malaga was, but it couldn’t be longer than 2 hours. If we got to Madras before 5 PM and I still felt fresh enough to fly, maybe we’d continue the trip and get home the same day we left. Was that even possible?

We still had to get to Madras, though. That was just 154nm away heading 337°. I took off into the wind and got right on course.

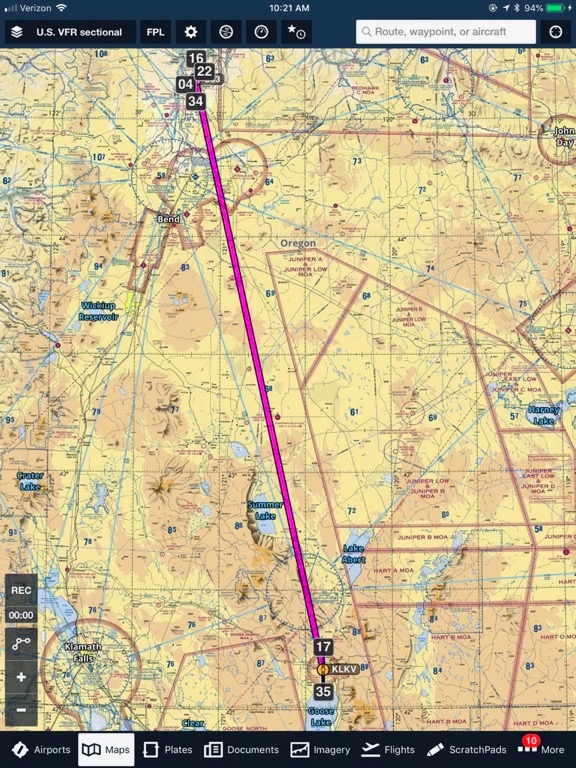

Our plotted course from Lakeview (LKV) to Madras (S33), OR. We pretty much followed this route exactly.

More boring desert mountains and valleys. Honestly, I was really done with it. It was only the lava fields that perked us up. They started when we were abeam the half-full Summer Lake and reappeared sporadically all the way to Redmond.

By the time we got near Redmond, we were back in civilization. We flew over a bunch of really nice homes along the river just east of Redmond that looked impractically large for anyone with fewer than a dozen kids but also beautiful. I talked to Redmond tower to tell them I wanted to transition along the east side of their airspace to Madras and got permission to do so. The only other pilots flying were flight school students with heavy Asian accents.

By this time, I was back over familiar ground. I’d flown Zero-Mike-Lima between the Wenatchee area and Bend, just south of Redmond, at least a dozen times. Although I had never landed at Redmond or Madras, I’d visited both on my midlife crisis road trip. (I really need to repost all the blog posts I wrote way back then and explain again why I made that trip.) Even though I was still quite a distance from home, I felt like I was close.

We touched down at Madras at about 4:30 PM.

Other than a backache from sitting in the same position for so long, I felt fine. I fueled up and worked Foreflight to plan the last leg of the trip. It told me the total flight time would be about 90 minutes. Shit. That was a no-brainer. I could certainly do another hour and a half of flying. We’d get home long before sunset, save the cost of a night in a motel, and be able to have a nice relaxing dinner at home. Best of all, I’d be able to sleep in my own bed and we could get an early start at fun things the next morning.

Janet agreed. Seriously, I think Janet is the best travel companion I’ve ever had. She’s realistic, adventurous, and has good ideas. And unlike one person I’ve traveled with extensively in the past — and he knows who he is — she doesn’t start an argument over every change of plans by saying, “But I thought we were going to….” [Insert eye roll emoji here.]

So after stopping in the very nice FBO to tell the woman there that I wouldn’t need the courtesy car after all, we climbed back on board and headed the rest of the way home. That meant steering 359° and flying just 166nm.

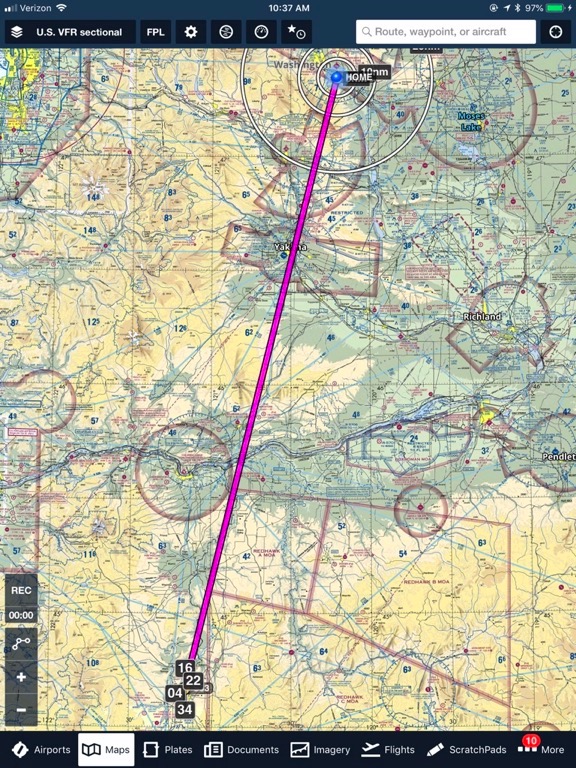

He’s the last leg of our trip, plotted on Foreflight.

This was mostly very familiar terrain. Although I’d flown this way before, I’d never started from Madras, so my flight path was a little farther west than it normally would be. We got great views of the Deshutes River that I normally don’t get. We still passed right over the top of Biggs, OR before crossing the Columbia River. That’s when Janet got her first glimpse of our extensive wind farms; there are literally hundreds of wind turbines between northern Oregon and the Wenatchee area.

I think it was on this leg that we started talking about a name for the helicopter. Janet names all her vehicles; I seldom name mine. But although Three-Four-Delta is pretty easy coming off the tongue, it just doesn’t seem quite right. We talked about naming it Blue or Blew or Bleu. Or one of those with “Mr.” in front of it. That got me thinking of the old ELO song, Mr. Blue Sky. Now that might seem like a deep cut to you, but I was an ELO fan and really loved this song — back in the 1980s. The chorus seems right:

Hey there mister blue

We’re so pleased to be with you

Look around see what you do

Everybody smiles at you

(Weren’t the 1980s grand in a funny sort of way? We were so innocent back then.)

Anyway, that’s what I was thinking of. I don’t think I mentioned it to Janet. I didn’t think she’d know the song. As I write this, I think Mr. Bleu might be a good name. Not Mr. Blue because the damn thing doesn’t look blue in most of the photos I take.

Meanwhile, the weather was deteriorating. The sun had been behind clouds for much of the previous leg of the trip and came out for a short time in northern Oregon. Then it slipped behind the clouds again. We caught a few glimpses of the top of Mount Hood but didn’t see any sign of Mount Adams or Mount Rainier, both of which would be in-your-face visible on a clear day. The only wind was a tailwind and there was no turbulence. But the farther north we got, the closer the clouds were to the ground. There was mountain obscuration west of Goldendale (hiding Mount Adams) and I started wondering whether we’d have to make any detours on our planned route.

Meanwhile, we saw wild horses on the Yakama Indian Reservation, which is no surprise to me. I always see wild horses there. There are actually stretches where you can see them from the road (route 97) when you’re driving though.

South of Yakima, I called the tower and told them I wanted to transition on the east side of their space. The controller cleared me and I continued north. I showed Janet where a big pieces of a mountainside has been sliding and will likely come down within the next few years, blocking the freeway and possibly the Yakima River there. (It’s been on the news.) The drop was pretty easy to see from the air.

Then we were flying up the Yakima River toward Ellensburg. When we flew over the last mountain ridge before the valley at Ellensburg, I could see the back side of Mission Ridge. The clouds were touching the ground there. I’d be crossing the ridge not far from there, but so far, it looked clear enough to keep going. So I did.

We climbed with the terrain, always staying east of where the clouds were touching the ground. I had hoped to come over Jumpoff Ridge just behind my home, but miscalculated and came over west of there, not far from Stemilt Hill. So I descended as I steered northeast, flying past my neighbors homes on the west end of the road to announce my arrival. The few that heard me told me later that they were happy to see me back with a replacement helicopter. (There are only a few Seattle-spoiled NIMBY assholes here who give me grief.) I showed Janet my home from the air and then came in for a landing at a neighbor’s home nearby. We’d already established a landing zone for me so I came right in and set down where I was supposed to.

Mr. Bleu in its temporary parking space. I shot this the other day when I went back to put in its cockpit cover.

It was 6:30 PM.

We’d been traveling for just under 11-1/2 hours and, if you figure the time spent on fuel stops, the total flight time was about 9-1/2 hours. I was tired, but not exhausted. It was glad to be home, glad not to have to deal with finding a decent hotel room at a decent price at a place that wouldn’t give me grief about staying with a dog. And I was especially glad to not have to fly again in the morning. I had had enough.

We unloaded the helicopter and loaded up my truck. I used the tailgate to put on the blade tie-downs. I locked the doors. I’d put the cockpit cover on another day.

Ten minutes later, we were home and I was opening a bottle of sparkling wine to celebrate the new arrival of Zero-Mike-Lima’s replacement.