My geologger tells the whole story.

Everyone who reads this blog or knows me understands that I am a gadget queen. I have all kinds of little gadgets that I use daily.

My GPS logger, described in some detail here, is one of my multi-purpose gadgets. Although I purchased it primarily to geotag photographs, I also use it when flying to get an exact record of where I’ve been.

I had my GPS logger running for the entire length of my flight from Seattle, WA to Page, AZ last week. As I discovered this morning when I looked at the tracks on Google Earth, it faithfully documented my Pendleton, OR area scud-running attempts.

Scud-running, in case you’re not familiar with the term, is a pilot’s attempt to get around bad weather in order to travel from point A to point B. Normal pilots do not attempt scud running unless they really need to get somewhere — this isn’t something you do on a pleasure flight. It’s also not something a pilot attempts unless he really thinks there’s a way through or around the weather in his path. Scud running is infinitely easier and safer in a helicopter than an airplane. We can make tighter turns and land without an airport when things get really bad. You could argue that scud-running is dumb and I don’t think I’d argue with you very much.

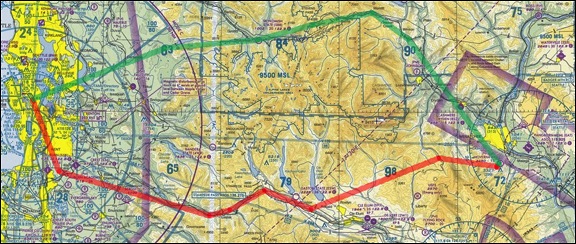

Here’s what my September 9 scud-running attempts look like on Google Earth:

The red line is my arrival in the area the night before. I landed at the Pendleton airport, fueled up, then flew a few more miles to the Bi-Mart parking lot next door to the Red Lion hotel where I spent the night. The Bi-Mart was closed and its parking lot was empty. It made a good LZ that would ensure an early departure the next day.

In the morning, I made my first attempt to get across the mountains. That’s the white line and it tells a pretty good story. I headed southeast, got up into the mountains, and attempted to find a way through. The lower line that comes to a point and doubles back is where I made my first U-turn in a canyon. I followed a canyon back out of the mountains and tried again by heading northeast. Again, I couldn’t get through and had to make a turn in a canyon. The yellow line, by the way, is I-84/Hwy 30; I’m pretty sure parts of the road were in fog. I returned to the airport and started waiting. That attempt took nearly an hour and 13 gallons (1/4 tank) of fuel — obviously, scud running isn’t something you attempt without a lot of fuel on board. (Makes for a bigger fire when you crash, though.)

At noon, I tried again. The blue line indicates my attempt to follow some railroad tracks up into the mountains. I realized pretty quickly that I wasn’t going to make it and doubled back. The post here about my new Hero camera (another gadget) includes video of this attempt shot as a time-lapse.

The green line is where I finally made it and got on course. It was 1:45 PM when I left the airport. I made it as far as North Salt Lake City before dark, dodging rainstorms and clouds a good part of the way.

Scud running is dangerous and I don’t do it without full understanding of that danger. Not once did I ever lose sight of the ground or immediate surroundings. When I realized I could not go forward the way I was going, I went back. As you can clearly see by shape of the white line U-turns I made, I was required to turn in two very tight places. These are turns that an airplane could not accomplish, especially since they were made in narrow canyons with no view over the canyon walls. The photo here shows how low the clouds were on that third attempt — the successful one. At several points, I was 200-300 feet below the clouds.

Scud running is dangerous and I don’t do it without full understanding of that danger. Not once did I ever lose sight of the ground or immediate surroundings. When I realized I could not go forward the way I was going, I went back. As you can clearly see by shape of the white line U-turns I made, I was required to turn in two very tight places. These are turns that an airplane could not accomplish, especially since they were made in narrow canyons with no view over the canyon walls. The photo here shows how low the clouds were on that third attempt — the successful one. At several points, I was 200-300 feet below the clouds.

I did a lot of scud running this past summer. That’s probably the nicest part of being back in Arizona: I seldom have to run the scud here.

I left Wenatchee Heights with my 5th wheel RV hooked up behind my husband’s Chevy pickup. The first day’s drive was relatively short: from Wenatchee Heights to Walla Walla, a distance of only 190 miles. Only a small portion of the drive was on a freeway (I-90); the rest was on back roads through farmland.

I left Wenatchee Heights with my 5th wheel RV hooked up behind my husband’s Chevy pickup. The first day’s drive was relatively short: from Wenatchee Heights to Walla Walla, a distance of only 190 miles. Only a small portion of the drive was on a freeway (I-90); the rest was on back roads through farmland. In Walla Walla, I stayed at the

In Walla Walla, I stayed at the  On Friday night, I got the trailer hooked up again and mostly ready to go. I needed to be on the road early for the next leg of my trip: from Walla Walla, WA to Draper, UT (south of Salt Lake City), a distance of 606 miles. I was on the road not long after dawn. The route took me south almost to Pendleton, OR, then onto I-84 through Oregon and Idaho and down into Utah, where I picked up I-15. The landscape started with farmland, then mountains, then more flat farmland, then more mountains, and then finally into the Salt Lake basin. I’d driven the route before with my underpowered Ford F150 pickup towing my old 22-foot Starcraft. It wasn’t fun then; Saturday’s drive was much more tolerable. I stopped three times for fuel and twice for food. It was very unlike me to make so many stops; I usually try to get food and fuel on the same stop, but the situation made that tough. I rolled into Draper, UT’s Camping World parking lot at 6:15 PM local time, just 15 minutes after the store closed. I’d called the week before and knew I could park out back, so I did. I even got to hook up 50 amp power.

On Friday night, I got the trailer hooked up again and mostly ready to go. I needed to be on the road early for the next leg of my trip: from Walla Walla, WA to Draper, UT (south of Salt Lake City), a distance of 606 miles. I was on the road not long after dawn. The route took me south almost to Pendleton, OR, then onto I-84 through Oregon and Idaho and down into Utah, where I picked up I-15. The landscape started with farmland, then mountains, then more flat farmland, then more mountains, and then finally into the Salt Lake basin. I’d driven the route before with my underpowered Ford F150 pickup towing my old 22-foot Starcraft. It wasn’t fun then; Saturday’s drive was much more tolerable. I stopped three times for fuel and twice for food. It was very unlike me to make so many stops; I usually try to get food and fuel on the same stop, but the situation made that tough. I rolled into Draper, UT’s Camping World parking lot at 6:15 PM local time, just 15 minutes after the store closed. I’d called the week before and knew I could park out back, so I did. I even got to hook up 50 amp power. On Sunday, @AnnTorrence picked me up for a drive to Ft. Bridger, WY. There was a

On Sunday, @AnnTorrence picked me up for a drive to Ft. Bridger, WY. There was a  Monday — Labor Day — was my last drive day. I drove from Draper, UT to Page, AZ, a distance of 370 miles. I got a very early start, pulling out of the parking lot at 6:30 AM local time. By the time I stopped for fuel two hours later, I’d already gone more than 100 miles. (I parked with the big rig trucks and discovered that my rig was about as long as theirs.) This part of the drive was mostly on I-15, but started east on route 20 to Highway 89, which took us all the way to Page. The roads were mountainous and there was a lot of climbing and descending. There were also a lot more vehicles on the road, making driving a bit more of a chore.

Monday — Labor Day — was my last drive day. I drove from Draper, UT to Page, AZ, a distance of 370 miles. I got a very early start, pulling out of the parking lot at 6:30 AM local time. By the time I stopped for fuel two hours later, I’d already gone more than 100 miles. (I parked with the big rig trucks and discovered that my rig was about as long as theirs.) This part of the drive was mostly on I-15, but started east on route 20 to Highway 89, which took us all the way to Page. The roads were mountainous and there was a lot of climbing and descending. There were also a lot more vehicles on the road, making driving a bit more of a chore. The only food stop I made along the way was at the Thunderbird Restaurant at Mount Carmel Junction. The place is a bit of a tourist trap, but it does have good “ho-made” pies (whatever that means). Odd thing happened when I tried to leave. They couldn’t give me a bill because the computer was down. Apparently no one knows how to do basic math. All I had was a piece of pie with ice cream and an iced tea. They apparently expected me to wait until the computers came back online. With Alex the Bird in the front seat of the car, that was not an option. Finally, my waitress disappeared into the kitchen where she may have used her “lifeline” to get help with this difficult math problem. The verdict was $7.79. I was afraid to count my change.

The only food stop I made along the way was at the Thunderbird Restaurant at Mount Carmel Junction. The place is a bit of a tourist trap, but it does have good “ho-made” pies (whatever that means). Odd thing happened when I tried to leave. They couldn’t give me a bill because the computer was down. Apparently no one knows how to do basic math. All I had was a piece of pie with ice cream and an iced tea. They apparently expected me to wait until the computers came back online. With Alex the Bird in the front seat of the car, that was not an option. Finally, my waitress disappeared into the kitchen where she may have used her “lifeline” to get help with this difficult math problem. The verdict was $7.79. I was afraid to count my change. My husband, who’d flown up in his plane and spent a few hours swimming in the lake, met me at the lodge restaurant for lunch. Afterwards, we put fuel in the truck and parked it (temporarily) at Page Municipal Airport. I gathered my belongings — forgetting only two things, one of which was vital — and we loaded into Mike’s plane. Then we started the long (90 minutes), hot (90°F+), and bumpy (I almost got sick) flight to Wickenburg. The only sights of interest along the way — keeping in mind that I make that flight about 1000 feet lower at least a dozen times a year — were a handful of forest fires east of our Howard Mesa place and a heavy rain shower coming out of a remarkably small cloud near Granite Mountain.

My husband, who’d flown up in his plane and spent a few hours swimming in the lake, met me at the lodge restaurant for lunch. Afterwards, we put fuel in the truck and parked it (temporarily) at Page Municipal Airport. I gathered my belongings — forgetting only two things, one of which was vital — and we loaded into Mike’s plane. Then we started the long (90 minutes), hot (90°F+), and bumpy (I almost got sick) flight to Wickenburg. The only sights of interest along the way — keeping in mind that I make that flight about 1000 feet lower at least a dozen times a year — were a handful of forest fires east of our Howard Mesa place and a heavy rain shower coming out of a remarkably small cloud near Granite Mountain.