A beautiful place from the air.

About a month ago, I was contacted by a professional photographer named Mike who lives in the Chicago area. He and several of his friends were planning a photographic excursion to the southwest. They wanted to hire a helicopter for a photo shoot over Lake Powell.

About Lake Powell

If you don’t know anything about Lake Powell, here’s the short story. It was created back in the 1960s when the government built the Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River near what is now Page, AZ. It took only seven years to fill the huge lake with water. It acts as a reservoir, produces hydroelectric power, and offers recreational activities including boating, houseboating, water skiing, etc. Recently, the Navajo Nation built a marina at Antelope Point (near the entrance to Antelope Canyon) to generate sorely-needed revenue from on this huge lake in their backyard. The lake sits on the northeastern side of Arizona, stretching northeast into Utah.

I’d been houseboating on Lake Powell twice. I love it. Miles and miles of twisting canyons branch off from the main channel of the river. The shoreline is endless, the rock formations, cliffs, and hidden ruins are enough to keep any explorer busy for a lifetime. If I had my choice of living anywhere in the world, I’d live on a houseboat on Lake Powell. I love it that much.

Of course, there is a movement among conservationists to drain the lake. They claim that the Glen Canyon area was beautiful before the dam and that the lake has destroyed that beauty. They also point out numerous townsites and ruins that were inundated when water levels rose. My response to these people is that it’s too late. The damage is done. And how can you truly fault the decision makers for making some of the most remote desert terrain accessible to the general public? It could have been worse. They could have flooded the Grand Canyon, as they’d planned years ago. Or Yosemite. And come on, guys — we know there are many more beautiful places out there that are just as remote and inaccessible as Glen Canyon was.

Preparing for the Trip

Anyway, after getting the call from Mike, my first task was to call the National Park Service to make sure I could do such a flight. The airspace over Grand Canyon is regulated and I wasn’t sure what kind of regulations existed for The Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, in which the lake sits. I spoke to a ranger in the law enforcement area. He told me that I could do the photo shoot. He suggested that I not fly low over any of the marinas (duh) and reminded me that landing was prohibited anywhere except at a landing strip.

Mike and I made arrangements. I explained I’d need a credit card number and would charge him $1,000 if I flew up to Page and he cancelled. He was fine with that. We set two dates — one in case the first was bad weather — and I sent him a contract.

The month passed quickly. I’ve been unbelievably busy with the helicopter these days, actually making money with it. It seems that my rates are lower than rates charged by other companies with similar (or better) equipment. Even when I charge for ferry costs, my total cost is far below other companies. Understand that I’m not trying to undercut anyone. I just have much lower overhead and am satisfied with a smaller chunk of profit. So my phone has been ringing incessantly. This week, for example, I had custom charters totaling an estimated 16 hours of flight time. While that might be peanuts for large operators, it’s serious revenue for a small company like Flying M Air.

Will Weather Ruin It?

The flight was Thursday. I started checking the weather on Tuesday. It didn’t look bad, but it didn’t look good. Clouds, chance of T-storms, some wind. Not optimal conditions for a photo flight. I looked at my calendar and realized that with some juggling, I could switch the flight to Friday afternoon (after another flight at Lake Havasu), spend the night in Page, and offer them another flight in the morning. I e-mailed Mike. I didn’t get a response. I didn’t realize it, but he was already traveling.

On Wednesday, the weather forecast looked better. But I thought my idea was pretty good. I called Mike and left him a voicemail message on his cell phone.

Thursday morning came. I had a message on my cell phone from Mike. We were still on for Thursday. Fine. The weather forecast looked a little better anyway. I did all my morning stuff, packed a bag, and went out to the airport to prepare the helicopter for the flight.

I was literally stepping into the helicopter at 11:30 AM on Thursday to fly up to Page when my cell phone rang. It was Mike. He wanted to know about the weather. I told him what I knew. He talked to his friends. I heard him mention Friday as an alternative. Then he came back and said “They want to to it today.”

“Fine,” I said. “I’m on my way.” Then I said goodbye, hung up the phone, and turned it off.

I flew up to Page. It was a 1.7 hour flight — lucky for Mike; I had estimated 2 hours and I aways double my ferry time to get round trip ferry time. It was windy in Wickenburg, Prescott, Williams, and Grand Canyon. The wind didn’t let up until I reached the Little Colorado River. From that point on — about 30 minutes — it was a nice, smooth flight. The rest was rather tiresome.

I got to the airport at 1:30 PM. I was supposed to meet Mike at 2 PM. I turned on my cell phone. There was a message. It was from Mike.

“If you haven’t left yet, we want to change it to Saturday.”

Shit.

Well, he knew our deal. He’d signed the contract. If I flew up and he didn’t use me, it would cost him $1,000, which barely covered my costs.

We’re On!

But he showed up at the airport with four companions. I would take them up in two groups — three and then two. Mike would go in the second group. He wanted late afternoon light. The first group wasn’t as concerned about the light.

I went out with the FBO guy to take all the doors off the helicopter. We stored them in Classic Aviation’s hangar. Then the FBO guy drove us all over to the helicopter for the safety briefing and first flight.

The first minor difficulty was language. It appears that they were all from Russia (or some such place) and English was not their first language. We went out to the helicopter and I gave them a safety briefing. One of the men translated for the others to make sure they understood. Then I handed out life jackets, made sure they all put them on, and made sure they were all strapped in and their seatbelts were secured.

A word about the life jackets. I’d bought two of them for a photo flight over Lake Havasu that was scheduled months ago for the next day. The ones I bought were Mustang inflatable collars and they cost me $124 each. They’re small and comfortable to wear and do not automatically inflate when they hit water. The way I see it — and the salesperson at the company I bought them from agreed — you want to get out of the helicopter before you inflate the vest so you don’t get stuck in the helicopter. The vest inflates by pulling a rip cord that triggers an air cartridge.

So I had two of these deluxe life jackets and two standard life vests from our WaveRunner days. Although I’m not sure that they were required by the FAA for the flight, if they aren’t, they should be. After all, most of the flight would be conducted over water and not within gliding distance to land. That means if we had an engine failure, we’d be swimming. And I don’t know about you, but if I crashed a helicopter into a lake, I’d probably need some flotation assistance. Otherwise, I’d probably drown in my tears as I watched my shiny red investment sink.

Not that I planned to go swimming, mind you. But better safe than sorry.

As we climbed aboard the helicopter, the weather was quickly deteriorating to the east. There was a huge cloud of dust near the Navajo Power Generating Station — a cloud that meant dust storm. The wind was coming from that direction, so there was a chance it would be at the airport soon. I still needed to start up, warm up, and take off. Fortunately, the lake looked clear — amazing how localized weather can be out here.

I got the onlookers away from the helicopter and started up. We took off into the wind with the dust storm still at least three miles away. I turned toward the lake, crossed over the new Navajo-owned marina at Antelope Point, and headed toward Padre Bay, where Mike had told me to take them.

First, the Amateurs

Out over the lake, it was sunny. But the sunlight, filtered through a thin layer of clouds, was softer than usual for the desert. Not perfect, but nice enough for photography.

I flew around for a while before one of my passengers started giving me directions of the “go left,” “go right” variety. That soon changed to “Please stop in this place” and “I want what you see on my side.” He meant he wanted me to hover and turn. He didn’t like taking photos from a moving helicopter. So I’d be moving along at about 80 knots to get from one place to the next and he’d say “Please stop in this place,” aparently expecting me to put on the brakes and bring it into an abrupt hover. I got a lot of quickstop practice, as well as practice hovering out of ground effect high over the lake with pedal turns to get the view he wanted on his side of the helicopter. Then, when it was time to start moving again, I’d try to fly slowly so the next stop would be smoother. But he’d tell me to go faster to get to the next place.

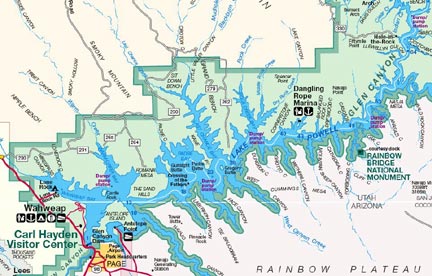

The area of Lake Powell where we flew. Click here for the full-sized map in PDF format (2.9 MB).

The other passengers didn’t make any requests at all. The woman beside me had a video camera and she took pictures of everything — the view, the controls, her face, the guys behind her, and even her feet. The passenger behind me was the one with good English skills and he’d translate for his companions when needed. He just took photos out his side and occasionally out the side his companion was shooting on. They were both using digital cameras with long lenses and I often had to move far away from a scene so they could shoot it.

We flew over some of the most spectacular scenery I’ve ever flown over. The lake level is relatively low, but the water is still finding its way into narrow canyons that twist and turn into the sandstone. The rock formations were magnificent; the reddish colors looked incredible against the blue of the water and the partly cloudy sky. It was a bit hazy, making the mountains of Utah look more distant than they really were. But Navajo Mountain was a clearly defined bulk nearby, with snow on the ground among the trees on its north side.

We flew over some of the most spectacular scenery I’ve ever flown over. The lake level is relatively low, but the water is still finding its way into narrow canyons that twist and turn into the sandstone. The rock formations were magnificent; the reddish colors looked incredible against the blue of the water and the partly cloudy sky. It was a bit hazy, making the mountains of Utah look more distant than they really were. But Navajo Mountain was a clearly defined bulk nearby, with snow on the ground among the trees on its north side.

We went quite far uplake, passing Dangling Rope Marina, which is only accessible by boat. I had a map of that area of the lake with me and I consulted it. Sure enough, Rainbow Bridge was nearby. I asked them if they wanted to see it and they didn’t know what it was. I tried to explain, then just took them. They were suitably impressed. The light was shining just right on it and there were no people down there to bother with the noise we made during our short visit.

In fact, the lake was pretty much empty. The high season hasn’t started yet and, on a Thursday, there weren’t many boaters around. We did see a few houseboats already camped for the night, as well as a bunch of campers with tents and powerboats. I’m a bit envious of the people with boats — although I could see much more than they could and explore more of the lake in less time, I couldn’t land, get out, and explore on foot. Boaters have that option.

We went as far upriver as Hole in the Rock, passing the confluence of the San Juan River along the way. Then it was too boring (for them, not me!) and they wanted to go back to where we’d first started shooting photos, in Padre Bay. Finally, they were finished and we headed back to the airport. The dust storm was long gone and, although it looked cloudy to the south and the skies there threatened rain, the weather at the airport was not an issue at all. We landed with 1.7 more hours on the Hobbs.

Next, the Professionals

I took on another 25 gallons of fuel and swapped passengers. Now I was flying the more serious photographers, Mike and his friend Igor. Unfortunately, the sun had slipped below some even thicker clouds and the light was softer than before. It wasn’t bad at the beginning of the flight, but the longer we flew, the worse the light got. It wasn’t late — only about 4:30 PM MST and at least two hours before sunset — but the clouds were ruining the show. I could tell Mike was very disappointed, but there was nothing I could do about it.

Mike was satisfied to simply fly slowly around the area, pausing now and then to manueuver the helicopter so he could take a shot. He and Igor were using professional camera equipment — digital, of course — and Mike spent a lot of time checking each photo in a shaded preview screen before taking his next shot. We covered Padre Bay and headed upriver. Since were were so close to Rainbow Bridge at one point, I took them to see it, but the light was bad by then and the shots wouldn’t have come out very well. They satisfied themselves taking pictures of the slot canyons and the swirls the rocks and water made when viewed from above. Really dramatic stuff. I wished I could shoot photos, too, but both hands and feet were kept quite busy.

Mike and Igor were a funny team. Mike, sitting next to me, would ask Igor a question like, “What do you think, Igor? Where do you want to go?” And Igor just wouldn’t reply. Not at all. Like he hadn’t heard him. At one point, I said, “Igor? Can you hear us?” And he pushed his talk button (I had the voice-activated feature turned off because of the wind in the microphones) and told us he could. But the next time Mike asked a question, it would go unanswered. It was driving Mike nuts and making it difficult for me not to laugh.

Done for the Day

After 1.4 hours, we landed back at the airport. By then, the light was terrible. It was nearly 6 PM and the FBO was scheduled to close. I needed to top off both tanks and retrieve my doors, then make some kind of arrangement for transporation to town, where I planned to spend the night. (I had enough light to get to Grand Canyon or Williams before dark, but the clouds looked thick to the south and I didn’t want to have to turn back. There’s nowhere else to go out there. I didn’t think that dropping in on a Navajo family living 40 miles from pavement would be a good idea.)

Mike and I settled up the bill with his charge card. Although he looked disappointed, he told me that it had been good. I wish it had been better. He spent a lot of money — he had to pay for my round trip ferry costs, too — and if he didn’t get the kind of photos he wanted, it was money down the drain.

Fortunately, the lone FBO guy took pity on me and gave me the keys to the courtesy van for my overnight stay. I had to be back at the airport at 5:30 AM for a 6:00 AM departure to Lake Havasu City.

But that’s another story.

I’d woken that morning in Montana, at a friend’s house, and had taken the scenic route south, through Yellowstone National Park. South of that park, I reached Jackson Lake with this late afternoon view of the Grand Tetons.

I’d woken that morning in Montana, at a friend’s house, and had taken the scenic route south, through Yellowstone National Park. South of that park, I reached Jackson Lake with this late afternoon view of the Grand Tetons.

I couldn’t remember where this photo was taken, either. I knew it was in Maine and I knew I’d taken it on one of our outings with John and Lorna. So I e-mailed Lorna a copy of the image and asked her. The response came back almost immediately: Samoset Resort in Rockland, ME.

I couldn’t remember where this photo was taken, either. I knew it was in Maine and I knew I’d taken it on one of our outings with John and Lorna. So I e-mailed Lorna a copy of the image and asked her. The response came back almost immediately: Samoset Resort in Rockland, ME. You also can’t see the building at the end of breakwater about a mile from where this photo was taken. Here it is. It was a lighthouse and apparently still functions as one. But it’s closed to the public, so you can just walk around it or onto its stone steps. We spent some time sitting out in the sun, watching the boats go by. It was a peaceful, relaxing place. There was some fog in the trees on the other side of the channel — the same fog we’d walked through earlier in the day when visiting the Owl’s Head Lighthouse. (Did I get that one right, Lorna?)

You also can’t see the building at the end of breakwater about a mile from where this photo was taken. Here it is. It was a lighthouse and apparently still functions as one. But it’s closed to the public, so you can just walk around it or onto its stone steps. We spent some time sitting out in the sun, watching the boats go by. It was a peaceful, relaxing place. There was some fog in the trees on the other side of the channel — the same fog we’d walked through earlier in the day when visiting the Owl’s Head Lighthouse. (Did I get that one right, Lorna?) I took this photo of John and Lorna on the way back to the car. John’s not an easy guy to get a picture of. It seem like every time you tell him to stand still and pose for a picture, he acts like he doesn’t believe someone’s really going to take his picture. So you have to take a few of them in a row for one of them to come out natural enough to use. This one gets them both.

I took this photo of John and Lorna on the way back to the car. John’s not an easy guy to get a picture of. It seem like every time you tell him to stand still and pose for a picture, he acts like he doesn’t believe someone’s really going to take his picture. So you have to take a few of them in a row for one of them to come out natural enough to use. This one gets them both. I dropped off the van at the airport, leaving the keys tucked inside the van’s logbook under the seat with a $10 contribution for fuel. It took five tries to get the combination right on the locked gate to the ramp. There was no one around. I walked out to the helicopter just as the sun was rising over Tower Butte and Navajo Mountain to the east. The air, which had been completely still, now stirred to life with a gentle breeze. There was enough light for a good preflight and I took some time stowing my bags and the life jackets so I’d be organized when I arrived at Havasu.

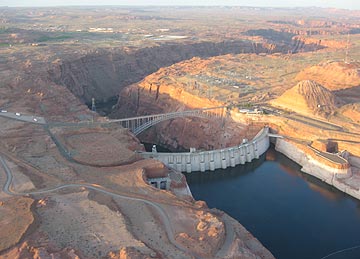

I dropped off the van at the airport, leaving the keys tucked inside the van’s logbook under the seat with a $10 contribution for fuel. It took five tries to get the combination right on the locked gate to the ramp. There was no one around. I walked out to the helicopter just as the sun was rising over Tower Butte and Navajo Mountain to the east. The air, which had been completely still, now stirred to life with a gentle breeze. There was enough light for a good preflight and I took some time stowing my bags and the life jackets so I’d be organized when I arrived at Havasu. I started the engine and warmed it up, giving the engine plenty of time to get to temperature. (Take care of your engine and it’ll take care of you.) At exactly 6 AM — right on schedule — I raised the collective, made a radio call, and took off toward the lake. I swung over the dam for a look and a photo before heading down the Colorado River, over Glen Canyon.

I started the engine and warmed it up, giving the engine plenty of time to get to temperature. (Take care of your engine and it’ll take care of you.) At exactly 6 AM — right on schedule — I raised the collective, made a radio call, and took off toward the lake. I swung over the dam for a look and a photo before heading down the Colorado River, over Glen Canyon. My flight path would take me south along the eastern edge of the restricted Grand Canyon airspace. In a way, it was ironic — less than two years ago, I’d earned part of my living as a pilot flying over the canyon every day, but now I can’t fly past the imaginary line that separates that sacred space from the not-so-sacred space I was allowed to fly. That didn’t mean I didn’t have anything to see. As I flew past Horseshoe Bend and over the narrow canyon, I could see reflections of the canyon wall on the slow moving river below. To the west were the Vermilion Cliffs with Marble Canyon at their base.

My flight path would take me south along the eastern edge of the restricted Grand Canyon airspace. In a way, it was ironic — less than two years ago, I’d earned part of my living as a pilot flying over the canyon every day, but now I can’t fly past the imaginary line that separates that sacred space from the not-so-sacred space I was allowed to fly. That didn’t mean I didn’t have anything to see. As I flew past Horseshoe Bend and over the narrow canyon, I could see reflections of the canyon wall on the slow moving river below. To the west were the Vermilion Cliffs with Marble Canyon at their base. I detoured slightly to the east, keeping to the left of the green line on my GPS that marked Grand Canyon’s airspace. The red rock terrain gave way to rolling hills studded with rock outcroppings and remote Navajo homesteads. I flew low — only a few hundred feet up — enjoying the view and the feeling of speed as I zipped over the ground, steering clear of homes so as not to disturb residents. I saw cattle and horses and the remains of older homesteads that were not much more than rock foundations on the high desert landscape.

I detoured slightly to the east, keeping to the left of the green line on my GPS that marked Grand Canyon’s airspace. The red rock terrain gave way to rolling hills studded with rock outcroppings and remote Navajo homesteads. I flew low — only a few hundred feet up — enjoying the view and the feeling of speed as I zipped over the ground, steering clear of homes so as not to disturb residents. I saw cattle and horses and the remains of older homesteads that were not much more than rock foundations on the high desert landscape. Then there were more homes beneath me and pinon and juniper pines. Wisps of low clouds clung to the mountains at my altitude. Past the mountain I’d been aiming for was the town of Seligman on Route 66 and I-40. I crossed over with a quick radio call to the airport and kept going.

Then there were more homes beneath me and pinon and juniper pines. Wisps of low clouds clung to the mountains at my altitude. Past the mountain I’d been aiming for was the town of Seligman on Route 66 and I-40. I crossed over with a quick radio call to the airport and kept going.

We flew over some of the most spectacular scenery I’ve ever flown over. The lake level is relatively low, but the water is still finding its way into narrow canyons that twist and turn into the sandstone. The rock formations were magnificent; the reddish colors looked incredible against the blue of the water and the partly cloudy sky. It was a bit hazy, making the mountains of Utah look more distant than they really were. But Navajo Mountain was a clearly defined bulk nearby, with snow on the ground among the trees on its north side.

We flew over some of the most spectacular scenery I’ve ever flown over. The lake level is relatively low, but the water is still finding its way into narrow canyons that twist and turn into the sandstone. The rock formations were magnificent; the reddish colors looked incredible against the blue of the water and the partly cloudy sky. It was a bit hazy, making the mountains of Utah look more distant than they really were. But Navajo Mountain was a clearly defined bulk nearby, with snow on the ground among the trees on its north side. What we could see, however, were haunting images of the coastline veiled with fog. Like this one, which I snapped at Otter Cove. I like this photo so much it’s currently the desktop picture on my laptop.

What we could see, however, were haunting images of the coastline veiled with fog. Like this one, which I snapped at Otter Cove. I like this photo so much it’s currently the desktop picture on my laptop.