I do a “search and rescue” and come up empty. Again.

First of all, understand that I don’t do search and rescue with my helicopter. I do search, but rescue isn’t part of the deal. I’m not equipped for it.

As for search — well, I’ll do it, but I don’t usually find what it is that we’re looking for. I’ve looked for hikers and dogs and even a truck and have not had success. I did find three out of four bulls once, but I think that was a fluke. Or just luck.

When people call and ask me to do a search, I tell them about my track record. I don’t want them to throw away $545/hour on a low-level helicopter flight that’s likely to come up empty. I basically talk them out of it. Hell, I did it a few weeks ago, when I was asked to search for a dog. Been there, tried that, failed.

I like money, but I hate taking it from disappointed passengers.

The First Call

I was at a wine tasting at Vistancia with some new friends when I got the call. It was so loud in the wine bar that I had to go outside to talk to the caller.

It was Edwin from another helicopter operation based in Glendale. A woman’s husband was sick and lost in the desert on the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation south of I-8. What was he doing there? I asked. Crossing in from Mexico illegally, he admitted. The woman needed someone to look for him, someone with a bigger helicopter than the R22s he operated. Would I do it?

I told him about my track record. I said I didn’t want to get in hot water with Border Patrol. He said I wouldn’t have to pick him up. I could just call 911 with his coordinates. He was sick and needed help. I told him he could have her call me the next day. I told him I was up as early as 7 AM. Then we hung up and went back to my wine tasting.

Red wines from Paso Robles are very good.

The Client Call

She called at 7:56 AM the next day. She had a Mexican accent, but her English was very good — she’d obviously been here a long time. She told me he’d been lost since Wednesday. She said he often had problems with tonsillitis and reminded me of the cold snap the week before. Nighttime temperatures had been in the 20s. She said his cousin had abandoned him in the desert and because it was on the reservation and they only had 4 rangers, no one was looking for him.

It was Sunday. If he really was sick, given the cold weather, he was likely dead.

But he could be alive. She apparently thought so.

I told her my track record. I told her that things were hard to find out in the desert.

She assured me that the area to search was small — only about 10 miles. She said it was mostly flat. She said he had a maroon blanket that should be easy to see.

I told her my rate. I told her I’d need a credit card deposit before I went to Glendale to meet them.

She said they’d pay cash. She said she’d fly down to Glendale with me to pick up the other two passengers for the search. She said one of them was familiar with the area. She said she’d talk to her brother-in-law and call back.

I went upstairs to get dressed.

She called back. She asked if I could do anything about the rate. I thought about the flight — 4 hours minimum. I thought about losing a loved one out in the desert. I thought about how she considered me her only hope. I thought about actually finding someone and saving his life.

I didn’t want to do it, but I made her a deal. And I reminded her again about my track record.

I couldn’t talk her out of it. She said she’d meet me at the airport in an hour.

The Clients

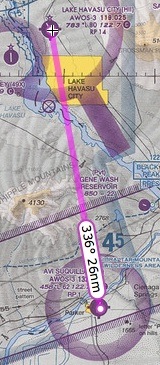

It was 10 AM when we met at the airport. The helicopter was already on the ramp. I’d refuel at Glendale to maximize flight time for the search.

She was surprisingly young — maybe in her late 20s — petite, pretty, and surprisingly calm. It’s odd, but the divorce crap I’ve been going through has really been affecting me in horribly negative ways, putting me in tears at odd times for the slightest thoughts. (After all these months, the memory of being locked out of my own house by my husband still gets me every time.) But this young woman, whose husband was sick and had been missing in the desert for more than half a week, was amazingly calm and collected. I believe it has to do with the way Mexican people deal with life problems. They’re so accustomed to hardship that they can be strong when most Americans would be falling apart.

There’s something to learn there.

As the helicopter was warming up, she showed me their wedding picture. It was a 5 x 7 print, a closeup shot, professionally done. She looked stunning, with flowers in her hair, a made-up face, and a white dress. He looked a little bit older than her with short hair and a nice suit. They looked like a nice couple. She looked at the photo with me, then slipped it back into her purse.

In the past month, two of my friends have become widows suddenly and unexpectedly.

Linda’s husband of 40+ years, Ron, died due to complications during what was supposed to be a relatively routine surgery. Just this afternoon, I got a thank you card from her for the fruit basket I sent. In it was a card about Ron’s life and a poem and photo. I read it and cried. I’ll miss Ron, too.

Pamela’s husband Terry died several hours after having a heart attack. They stabilized him in the hospital and said they were going to let him go home in the morning. She was sitting with him that night when she watched “the light leave his eyes.” She cried to me when she told me what a wonderful partner he had been.

These two women — and the young woman I flew for on Sunday — loved their husbands and their husbands loved them. They lost their husbands unexpectedly or even tragically.

Yet my husband, who has turned into a hateful, vindictive bastard, still lives. Why couldn’t he have died instead of one of them? Why couldn’t he have died before he broke my heart? Yes, I’d still be in pain, but at least I’d have the illusion of thinking that he still loved me when I lost him. And at least I’d have some closure by now.

Death is not fair. It takes the wrong people.

I thought about this young woman with her whole life ahead of her. I thought about her husband, who she loved and wanted to find. And I all I could think about was my husband, who had lied to me, cheated on me, locked me out of my home, and was trying to use Arizona law and the court system to take as much of my hard-earned money and assets as he could. Surely life would be better for both her and me if it were my husband sick and lost in the desert instead of hers.

We flew direct to Glendale. It was a 20-minute flight. I landed on the ramp and called the FBO for fuel. She went to the terminal to bring back the other passengers.

I had to get them back through the gate. It was two men — a younger man who was amazingly jovial, considering the situation — and an older, more heavyset man who didn’t speak much English. I did a safety briefing, loaded them on board, I started up, warmed back up, and headed out.

Along the way, they gave me texted GPS coordinates, which I punched into my Garmin 420 GPS. It took us 30 minutes to get there: Ventana, AZ.

The Story

The story had many versions which evolved during the course of the day. My clients were receiving texts throughout the flights. And later, when we landed at Casa Grande for fuel, we got even more information from a Border Patrol officer who met with us briefly.

The original story was this: Oscar and his Cousin had crossed the border on foot with a party from Sonoyta with a Coyote. Oscar had gotten sick, which slowed them down near Ventana. The Coyote and others had abandoned them because they were too slow. Oscar and his cousin got as far as Ventana, where they got water. Then they continued on, walking toward the glow of the Phoenix lights. Oscar got too sick to walk, so his cousin left him in “a flat area near a tank with water within 1 mile of a paved road between Ventana and Kaka.” His cousin then walked for 10 hours before he got to Kaka at about 5 PM and turned himself in at a house. Border Patrol picked him up, but it was too late in the day to start a search for Oscar.

There was some talk about a pipeline that the illegals often followed on their trip. The pipeline went right through Kaka, but didn’t go anywhere near Ventana.

My clients had some information from Oscar himself, when he called on a cell phone from where he’d been left. He was apparently very sick but in good spirits, telling his wife that he wanted to surprise her with his visit. I didn’t ask why he was illegal, whether she was, or anything else like that. It wasn’t my business. I didn’t care.

And my clients also had some information from the Coyote, but it was clearly incomplete.

So our initial search area was between Ventana and Kaka a distance of only 4.5 nautical miles.

The First Flight

I wish I had photos to show you how flat and featureless most of the terrain between Ventana and Kaka is. But I don’t. I wasn’t expecting anything beautiful, so I didn’t rig up my cameras for the flight.

If you’re reading this and you live anywhere near a metropolitan area, I guarantee you’ve got no idea of the kind of remote and empty terrain I’m writing about here. You can go 50 miles or more without crossing a paved road or seeing any kind of man-made structure. There’s no shelter from the sun or the wind. During the day in the wintertime, it can get into the 80s; the same night it can go down into the 20s. There are coyotes in the flats and mountain lions in the hills. This is the landscape Mexican immigrants often walk through to get a better life in America.

From Glendale, we flew past the Estrella mountains and into a long valley between mountain ranges. The ground was mostly flat, with dusty soil, and scrubby cacti, mesquite, palo verde, and other typical Sonoran desert vegetation. The only thing missing were saguaro cacti. They were all on the rocky mountainsides.

In some places, the ground was covered with tall yellow grass. In other places, it was sand. In still other places, it was eroded into shallow washes lined with somewhat taller trees. My chart showed some of the terrain as dry lake beds, but they were more grassy than the dry flat basins I’m familiar with.

We crossed the pipeline, which ran from the southwest to the northeast. The man familiar with the area, George, wanted me to go all the way to Ventana, but we began checking near cattle tanks — man-made ponds out in the desert designed to gather and hold water during rainstorms for cattle. We were looking for that maroon blanket.

A satellite view of the thriving metropolis of Ventana, AZ. That stuff that looks like dusty dirt? It is.

We got to Ventana. It was a settlement of about 50 buildings. It was miserable blotch on the desert landscape. I couldn’t imagine anyone wanting to live there. (Apologies to the people who do.) The only thing it had going for it was a paved road leading out of town.

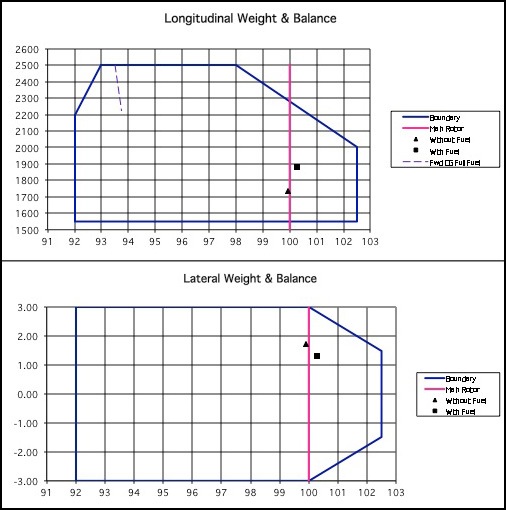

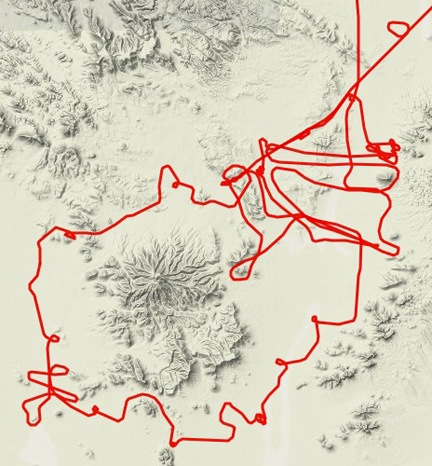

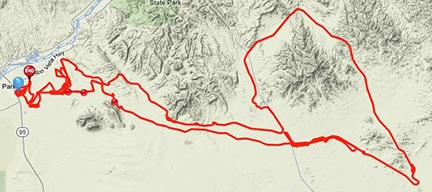

My actual track from the first search flight. I came in from the north, worked my way around the area, and then departed for fuel to the northeast.

I tried a search pattern between Ventana and Kaka. (Kaka was as bad as, if not worse than, Ventana.) George, kept directing me off my pattern. That was okay. If we searched where they wanted, they couldn’t blame me if we came up empty. But there was no sign of anyone — not even the usual trash left behind by illegals regrouping before moving on.

There were, however, wild horses. I have never seen so many wild horses in my life. They were all over the place in herds ranging from 5 to 20 animals. All different colors: brown, white, black, paint. They didn’t seem the least bit interested in us, even when we flew just a few hundred feet over their heads.

There were also shrines or memorials along the side of the roads. Crosses and hearts and flowers. I counted at least ten or twelve. Others had died in the area. Were they victims of car crashes or of the desert’s hostile terrain? Would there be a memorial near there for Oscar one day soon?

The Questions

As we got a better idea of the area, the questions started coming. If they were walking from Sonoyta to Phoenix along the pipeline, how had they gotten anywhere near Ventana? And if they were in Ventana, why did they walk northwest (instead of northeast) to Kaka? And why had it taken Oscar’s cousin 10 hours to walk from Ventana to Kaka, a distance of less than 5 miles? And if they were walking along the pipeline, how could they be within a mile from a paved road?

None of it made sense.

We followed the pipeline west past Kaka, exploring the low mountains in that area. I had strayed into a restricted area which, fortunately, was closed on Sundays. We found ourselves in another valley with the same featureless terrain and wild horses.

The pipeline road was littered with trucks and minivans — the vehicles stolen by Coyotes in Phoenix to smuggle illegals in. They drive them until they break and they leave them in the desert to rot. There were also wheels along the road. When a vehicle gets a flat, they change it and leave the old wheel behind.

And bicycles. Some of the people use stolen mountain bikes instead of walking. When the bikes are destroyed by the rough terrain, they’re simply left behind. I wondered if my bicycle, stolen last year from our Phoenix condo, was out in the desert nearby.

George directed me to fly south down a dirt road from the pipeline. That eventually dumped us in Hickiwan, another Indian village on a paved road. This one was a bit bigger. We saw a Border Patrol vehicle. We searched the area, around cattle tanks. I couldn’t understand why he’d be so close to a town and not go to get help. They told me he was very sick — too sick to walk. Again, I thought that he must be dead by now.

When George pointed southwest down the paved road between two big hills and told us that the Coyotes usually came up from there, I suspected that he’d worked with Coyotes in the past. He just knew the routes too well.

We followed the paved road to Vaya Chin, searching on the north side as we went. Then back up to Ventana, searching on the west side of the road. Then to Kaka again, where the paved road ended.

By that time, I needed fuel. Casa Grande was the closest airport with fuel and it was a good 20-minute flight away. So we took off northeast, following the pipeline most of the way. We even did one or two brief searches on either side of the pipeline. Of course, this was nowhere near a paved road.

Fuel Stop

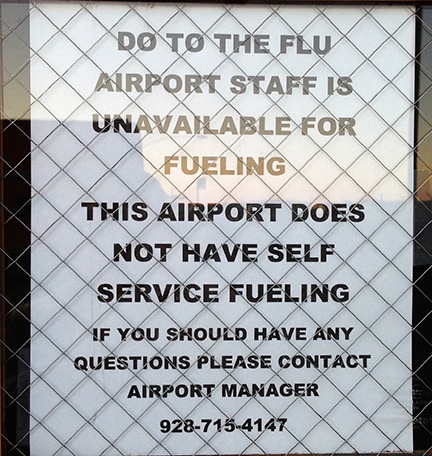

At Casa Grande, I let them out while I shut down the engine, refueled, and added a quart of oil. They were hanging out near the terminal building in the sun. It was a beautiful day in the high 60s with very little wind. They couldn’t ask for better weather for a search.

At various times, each of them were on the phone. At one point, my client called the Border Patrol guy who’d picked up Oscar’s cousin. He said he was in the area and would meet us.

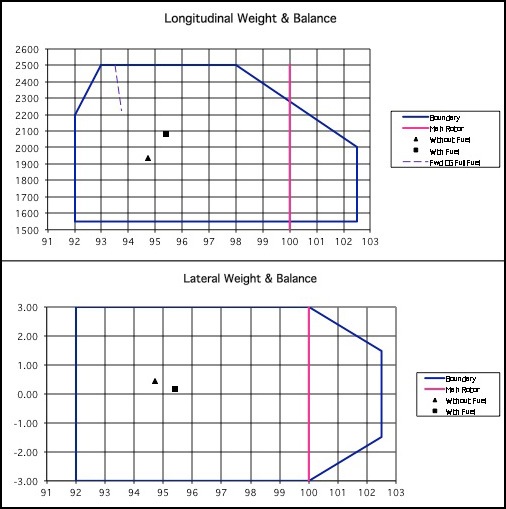

A while later, a hispanic guy showed up and introduced himself. By that time, I’d fetched a chart from my helicopter which clearly indicated each of the points of interest we’d searched near (see above). He proceeded to tell us the effort Border Patrol had put into finding Oscar. SUVs, ATVs, guys on foot, dogs, and even helicopters with infrared capabilities. They’d even gone so far as to follow tracks in the desert on foot as far as five miles. Nothing.

He mentioned looking for buzzards (vultures) — which I’d already been doing — and the fact that the infrared gear picked up body heat. Clearly, he didn’t think Oscar was alive at this point either.

I didn’t want my client throwing away more money, but if she wanted to keep flying, we would. It was already after 3 PM; the sunset would be at about 5:40 PM. We didn’t have much time. I mentioned this and asked her what she wanted to do.

Keep flying, she said resignedly.

So we said goodbye to the Border Patrol guy and climbed back on board. I made a beeline toward our original GPS point.

The Second Flight

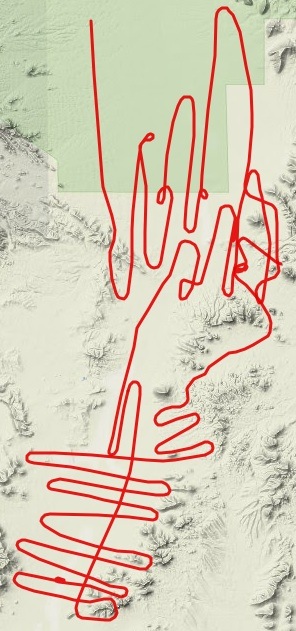

My phone’s battery was nearly dead, so I started this track on my iPad after we’d begun the second search. You can clearly see the search patterns I attempted.

We started in the vicinity of an old mine not far from the pipeline north of Ventana. We searched the valley to the west of there and I pretty much insisted on some sort of search pattern. Then we moved south of Ventana and Kaka, getting almost as far as Vaya Chin.

That’s when my client started getting text messages with more information. Oscar’s cousin had turned up in Mexico. He insisted that he and Oscar had walked through Ventana, stopping there to get water. He said he’d left Oscar within a mile of a paved road near a tank — in other words, it was the original story again. He said they’d been walking in the dark toward the bright lights of Phoenix (north-northeast). He wasn’t clear on how he’d gotten to Kaka, but it was late in the afternoon after he’d left Oscar in the dark.

So we began a search between Ventana and Kaka again, and then a pattern north of Ventana. I think we went too far north — after all, we should have stayed within a mile of the paved road — but I did what I was told. We came up empty.

And with the sunlight beginning to fade, we were also beginning to spook all those wild horses. When they heard us coming, they’d often start to run.

The light was pretty, with a golden hue and long shadows. But it was also difficult to see, especially when we faced the sun.

Finally, at around 5:30, I pulled the plug. I was getting low on fuel again and planned to go all the way back to Glendale — a 30-minute flight — to get more. It didn’t make sense to go to Casa Grande and then Glendale.

As we flew north, they kept getting texts. They talked about Ventana Mountain (Window Mountain) instead of the town of Ventana. They talked about bringing leaves from a tree near Oscar to Kaka where his cousin surrendered to Border Patrol. They talked about the Coyote being purposely vague and the locals not wanting to get involved. The last few mentioned that an Indian woman in Kaka claimed she knew exactly where Oscar had been left. If so, then why wait until the end of the day so long after the search had begun? Did she see the helicopter and think she could get some money from people who were that desperate to find the missing man? It seemed likely, since she said she wouldn’t take them anywhere without being paid. Still, there was nothing they could do other than try.

I felt bad for them. Very bad.

End of the Flight

We got to Glendale and I shut down. It was a little after 6 PM. They went out toward the parking lot while I arranged for fuel. I didn’t have enough to get back to Wickenburg.

My client returned, looking sad. She climbed on board, I got clearance from the tower to depart, and we headed northwest.

Along they way, she told me about how they’d married only three years ago. She told me about her first two pregnancies, both of which ended in miscarriage. She told me about her third pregnancy and the little girl they now had. She was clearly on the verge of tears when she told me how happy they were and how much he looked forward to being with her and his daughter.

I knew that Oscar was likely dead, his bones probably scattered by the coyotes and other desert carnivores who had found a free meal in an unexpected place.

And I thought again about my broken marriage and wished there was some way I could trade Oscar for the man who was tormenting me regularly.

We landed in Wickenburg and I let her go while I shut down. There was no reason to keep her from her daughter and the others who waited for news.

I asked her to call me if they found him.

And as I watched her walk away on the dark ramp, I decided that the next time I was asked to do a search like this, I’d say no.

Penny lounges in the sun under the desk in our hotel room.

Penny lounges in the sun under the desk in our hotel room.