March 24, 2013, 11:30 AM Edit: Got the airplane terminology wrong. Thanks to two airplane pilots for correcting me. I’ve edited the text to show the change. Sorry about the confusion. – ML

March 25, 2013, 2:15 AM Edit: Left out the word towers in a sentence.

Come on folks — it’s not as bad as you think.

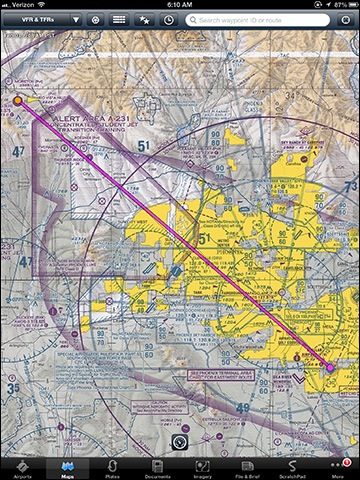

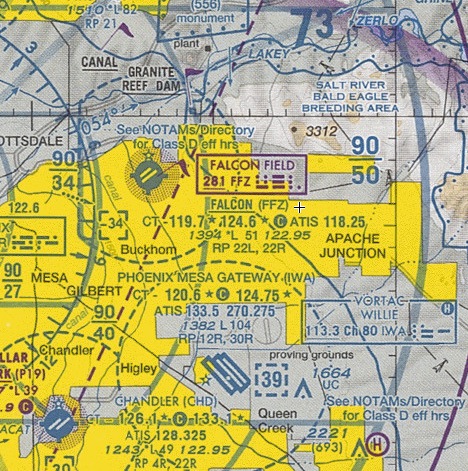

The control tower at Falcon Field Airport in Mesa, AZ is a typical Class Delta airport tower. (This is not one of the towers scheduled for closure.)

I’ve been reading a lot lately about the FAA’s upcoming airport tower closures. A list is out and there are 149 airports on it. The reduction of funding due to the sequester is making it necessary to close these contracted airport towers all over the country.

Most news articles, tweets, and Facebook updates that I’ve read about the closures are full of doom and gloom. Apparently, a lot of people believe that airport towers are required for safety. But as most general aviation pilots can attest, low traffic airports do not need towers.

What an ATC Tower Does

Air Traffic Control (ATC) towers are responsible for ensuring safe and orderly arrivals and departures of aircraft at an airport. Here’s how it works at a typical Class Delta airport — the kind of airports affected by the tower closures.

Most towered airports have a recording called an Automated Terminal Information System (ATIS) that broadcasts airport information such as weather conditions, runway in use, and any special notices (referred to as Notices to Airmen or NOTAMs). Pilots listen to this recording on a special airport frequency as they approach the airport so they’re already briefed on the most important information they’ll need for landing. The ATIS recording is usually updated hourly, about 5 to 10 minutes before the hour. Each new recording is identified with a letter from the ICAO Spelling Alphabet, or the Pilot’s Alphabet, as I refer to it in this blog post.

Before a pilot reaches the airport’s controlled airspace — usually within 4 to 6 miles of the airport — she calls the tower on the tower frequency. She provides the airport controller with several pieces of information: Aircraft identifier, aircraft location, aircraft intentions, acknowledgement that pilot has heard ATIS recording. A typical radio call from me to the tower at Falcon Field, where I flew just the other day, might sound something like this:

Falcon Tower, Helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima is eight miles north, request landing helipads with Kilo.

An airplane calling in might say something like:

Falcon Tower, Cessna One-Two-Three-Alpha-Bravo is ten miles east, request touch-and-go with Kilo.

Kilo, in both cases, is the identifier of the current ATIS recording.

The tower controller would respond to my call with something like:

Helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima, Falcon Tower, proceed inbound. Report 1 mile north for midfield crossing at nineteen hundred feet.

To the airplane, he might say something like:

Cessna One-Two-Three-Alpha-Bravo, Falcon Tower, enter right downwind for runway four right.

(If you want to see what these instructions mean by looking at a detailed airport diagram, here’s one for you.)

Of course, if the tower controllers were really busy or there was some sort of problem at the airport, the controller could say something like:

Aircraft calling Falcon Tower, remain clear of the class delta airspace.

That means the pilot can’t come into the airspace — which is marked on charts and many GPS models — until the tower clears her in. That happens very seldom.

This is the beginning of the conversation between the air traffic controller in the airport’s tower and the pilot. What follows is a dialog with the tower providing instructions and the pilot acknowledging those instructions and then following them. The controller’s job is to sequence airplane traffic on the airport’s runway(s), making sure there’s enough spacing between them for the various types of landings: touch-and-go, full stop, low approach, etc. In the case of helicopters — which is admittedly what I know best — the tower can either put us into the traffic pattern with the airplanes (which really isn’t a good idea) or keep us out of the airplane flow. The tower clears airplanes to land on the runway and gives permission to helicopters to land in “non-movement” areas.

At the same time all this is going on, the tower’s ground controller is providing instructions to airplanes that are taxiing around the airport, either to or from the runways. Aircraft are given taxi instructions that are sort of like driving directions. Because helicopters seldom talk to towers, I can’t give a perfect example, but instructions from the transient parking area to runway 4R might sound something like this:

Cessna One-Two-Three-Alpha-Romeo, Falcon Ground, taxi to runway four right via Delta.

Position and holdLine up and wait at Delta One.

These instructions can get quite complex at some large airports with multiple runways and taxiways.

Position and hold Line up and wait — formerly hold short position and hold — means to move to the indicated position and do not cross the hold line painted on the tarmac. This keeps the airplane off the runway until cleared to take off.

A pilot who is holding short waiting switches to the tower frequency and, when he’s the first plane at the hold line, calls the tower to identify himself. The tower then clears him to get on the runway and depart in the direction he’s already told the ground controller that he wants to go.

Air traffic control for an airport also clears pilots that simply want to fly through the airspace. For example, if I want to fly from Wickenburg to Scottsdale, the most direct route takes me through Deer Valley’s airspace. I’d have to get clearance from the Deer Valley Tower to do so; I’d then be required to follow the tower’s instructions until the controller cut me loose, usually with the phrase “Frequency change approved.” I could then contact Scottsdale’s tower so I could enter that airspace and get permission to land.

A few things to note here:

- Not all towers have access to radar services. That means they must make visual contact with all aircraft under their control. Even when radar is available, tower controllers make visual contact when aircraft are within their airspace.

- If radar services are available, tower controllers can ask pilots to Ident. This means pushing a button on the aircraft’s transponder that makes the aircraft’s signal brighter on the radar screen, thus making it easier for the controller to distinguish from other aircraft in crowded airspace. The tower can also ask the pilot to squawk a certain number — this is a 4-digit code temporarily assigned to that aircraft on the radar screen.

- Some towers have two tower controller frequencies, thus separating the airspace into two separately controlled areas. For example, Deer Valley Airport (DVT) has a north and south tower controller, each contacted on a different frequency. When I fly from the north over the top of the runways to land at the helipads on the south side, I’m told to change frequency from the north controller to the south controller.

- The tower and ground controllers coordinate with each other, handing off aircraft as necessary.

- The tower controllers also coordinate with controllers at other nearby airports and with “center” airports. For example, when I fly from Phoenix Gateway (IWA) to Chandler (CHD), the Chandler controller knows I’m coming because the Gateway controller has told him. Similarly, if a corporate jet departs Scottsdale (SDL) on an Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) flight plan, the Scottsdale controller obtains a clearance for that jet from Phoenix Departure or Albuquerque Center.

I should also point out two things from the point of view of a pilot:

- Dealing with air traffic control does add a tiny bit to the pilot’s workload. The pilot must communicate with the tower before entering the airspace, the pilot must follow the tower’s instructions (unless following those instructions is not safe, of course). I know plenty of pilots who would rather fly around a towered airport’s airspace than fly through it — just because they don’t want to talk to a controller. I’ll admit that I’ve done this quite a few times — I even have a winding route through the Phoenix area between Wickenburg and Chandler that avoids all towered airspace along the way.

- Air traffic control gives many pilots the impression that they are no longer responsible for seeing and avoiding other aircraft. After all, the tower sees all and guides aircraft to avoid each other. But there have been instances where air traffic control has dropped the ball — I experienced one myself years ago — and sometimes this can have tragic consequences.

Low Traffic Airports Don’t Need Towers

As you can probably imagine, the more air traffic coming and going in an airport’s airspace, the busier air traffic controllers are.

A very busy airport like Deer Valley, which has at least two flight schools, several helicopter bases (police and medevac), at least one charter operator, and a bit of traffic from corporate jets, can keep controllers pretty busy. In fact, one of the challenges of flying in and out of Deer Valley is being able to get a call in on the radio — it’s often a steady stream of pilot/controller communication. Indeed, Deer Valley airport was the 25th busiest airport in the country based on aircraft movements in 2010.

Likewise, at an airport that gets very little traffic, the tower staff doesn’t have much to do. And when you consider that there has to be at least two controllers on duty at all times — so one can relieve the other — that’s at least two people getting paid without a lot of work to do.

Although I don’t know every towered airport on the list, the ones I do know don’t get very much traffic at all.

For example, they’re closing four in Arizona:

- Laughlin/Bullhead City International (IFP) gets very little traffic. It sits across the river from Laughlin, NV in one of the windiest locations I’ve ever flown into. Every time I fly into Laughlin, there’s only one or two pilots in the area — including me.

- Glendale Municipal (GEU) should get a lot of traffic, but it doesn’t.

- Phoenix Goodyear (GYR) is home of the Lufthansa training organization and a bunch of mothballed airliners, but it doesn’t get much traffic. Lufthansa pilots in training use other area airports, including Wickenburg, Buckeye, Gila Bend, Lake Havasu City, and Needles — ironically, none of those have a tower.

- Ryan Field (in Tucson; RYN) is the only one of the three I haven’t flown into, so I can’t comment its traffic. But given the other airports on this list, I have to assume the traffic volume is low.

They’re also closing Southern California Logistics (VCV) in Victorville, CA. I’ve flown over that airport many times and have landed there once. Not much going on. It’s a last stop for many decommissioned airliners; there’s a 747 “chop shop” on the field.

They’re closing Northeast Florida Regional (SGJ) in St. Augustine, FL. That’s the little airport closest to where my mom lives. When she first moved there about 15 years ago, it didn’t even have a tower.

These are just the airports I know. Not very busy. I know plenty of non-towered airports that get more traffic than these.

How Airports without Towers Work

If an airport doesn’t have a tower — and at least 80% of the public airports in the United States don’t have towers — things work a little differently. Without a controller to direct them, pilots are responsible for using the airport in accordance with standard traffic patterns and right-of-way rules they are taught in training.

Some airports have Automated Weather Observation Systems (AWOS) or Automated Surface Observation Systems (ASOS) that broadcast current weather information on a certain frequency. Pilots can tune in to see what the wind, altimeter setting, and NOTAMs are for the airport.

When a pilot gets close to a non-towered airport, she should (but is not required to) make a position report that includes her location and intentions. For example, I might say:

Wickenburg Traffic, helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima is ten miles north, landing Wickenburg.

An airplane pilot might say:

Wickenburg Traffic, Cessna One-Two-Three-Alpha-Bravo is eight miles southeast. We’ll be crossing midfield at five thousand to enter right traffic for Runway Two-Three.

Other pilots in the area would hear that call and respond by making a similar position call. The calls continue as needed at the pilot’s discretion — the more aircraft in the area, the more calls I make just to make sure everyone else knows I’m out there and where I am. Pilots then see and avoid other traffic to land or depart the airport.

It sounds crazy, but it works — remarkably well. In Wickenburg, for example — an airport that gets a lot of pilots in training practicing takeoffs and landings — there might be two or three or even more airplanes in the traffic pattern around the airport, safely landing and departing in an organized manner. No controller.

And this is going on at small general aviation airports all over the country every single day.

What’s even more surprising to many people is that some regional airlines also land at non-towered airports. For example, Horizon operates flights between Seattle and Wenatchee, WA; Wenatchee is non-towered. Great Lakes operates between Phoenix or Denver and Page, AZ; Page is non-towered.

The Reality

My point is this: people unfamiliar with aviation think that a control tower is vital to safe airport operations. In reality, it’s not. Many, many aircraft operate safely at non-towered airports every day.

While the guidance of a tower controller can increase safety by providing instructions that manage air traffic flow, that guidance isn’t needed at all airports. It’s the busy airports — the ones with hundreds of operations every single day — that can truly benefit from air traffic control.

The 149 airport towers on the chopping block this year were apparently judged to be not busy enough.

I guess time will tell. And I’m certain of one thing: if there is any accident at one of these 149 airports after the tower is shut down, we’ll hear about it all over the news.

In the meantime, I’d love to get some feedback from pilots about this. Share your thoughts in the comments from this post.