I probably can’t give you the answers you want to hear but I can tell you what you need to consider when making this big decision.

Start Here.A lot of what I’m saying in this blog post can be found in my series about becoming a helicopter pilot: “So You Want to Be a Helicopter Pilot.” Do yourself a favor and read it. You can find the first part here.

And when you’re done with that — and the posts that those posts link to — try reading some of the posts in the Flying topic. Then search this site for keywords like careers, helicopters, flight training, etc. You’ll find lots more to read and learn from.

I’ve written a lot in this blog, especially over the past five years or so, about building a career as a helicopter pilot. With more than 2,400 posts on this site — including more than a few recipes, day-in-the-life stories, and rants that have nothing to do with flying — there’s a lot to wade through to get the information you want. Some folks think it’s a lot easier to just write me an email with specific questions about helicopter pilot careers. Easier for them, perhaps, but not for me. That’s why my Contact page has this section that appears before the contact form:

Career Advice/Pilot Jobs

I cannot provide career advice of any kind, whether you want to be a writer or a helicopter pilot. The posts in this blog have all the advice I’m willing to give the public. If you want my advice read them. There’s a pretty good chance that I’ve covered your question here in a blog post.

The Email Requests Still Come

Despite that, I still get at least two messages a month — using the form on that very page — asking me helicopter pilot career questions. Here’s a typical example; this one arrived yesterday:

Fascinating blog, lots of good perspectives. My son and I are considering this as a career for him, he is 19. We have made calls, visited a few schools, heard the sales pitches, heard the perspective of the job market from the perspective of the CFI’s and schools.

Your post from 2009 was bleak regarding the career prospectives. We get the need for moves required, the dues needed to put it, the cost, etc.

My question to you is, has your perspective changed at all since 2009?

Although the author did not specifically identify the 2009 post he was referring, I assumed he was referring to the most popular (of all time) post on this blog, “The Helicopter Job Market.” But a quick look showed me that that post dated from 2007. Not knowing what he already read makes it a bit difficult to review what I wrote in 2009 and update it. I do get the impression, however, that he just scratched the tip of the iceberg on career-related content here.

So I thought I’d spend this morning pointing him (and others) in the right direction to learn more, much as I did in “Helicopter Career Advice Sought…and Provided,” which was a reply to someone else’s email back in 2009. (That was apparently back before I instituted the “I can’t give you advice” policy on my contact page and may even have prompted me to adopt that policy.)

Important Points

You need to take all the advice I give on this site with a grain of salt. Why? Here are a few reasons:

- I am not a career counsellor. I have no training in career counseling and refuse to take responsibility for any actions taken by a reader who might consider my blog posts as career advice.

- I am not an industry insider. I am the owner/operator of a small, single-pilot helicopter charter business. I only had one flying job for another organization and that was a summer job back in 2004. My fingers are not on the pulse of the industry. I chug along in my own little world, running my business in accordance with applicable regulations with absolutely no intention of building my business beyond what I can handle.

- I did not get to where I am by following the typical pilot career path. I was fortunate in the early 2000s to have a writing career that paid extremely well. That money subsidized my flying business until it became profitable on its own. That’s why, after 13 years as a pilot and over 3,000 hours in helicopters I still don’t have my CFI certificate. Obviously, I can’t provide detailed advice on following a career path that I didn’t follow. I simply took a different path, one that would probably be very difficult for others to follow.

- I am not an employer. Although I do occasionally hire helicopter operators like myself to assist me in my summer agricultural work, I have never put any pilot on payroll or provided any career training for another pilot. How can I know what employers want?

All that said, I do know a lot of pilots and we do talk a lot about the industry. I have a very good relationship with the FAA. I also have a generous helping of common sense and have heard enough horror stories to form opinions I’m not afraid to share.

Doing Your Homework

One thing that struck me about this message was that it was written by the dad — not the possible future pilot. While this isn’t the first time a parent wrote to me — last time it was a mom — it does raise flags.

Why isn’t the son writing? Who’s doing the research? Who really wants this job? Is the dad pushing his son into a career he might not be interested in? Doesn’t the son care enough about this as a career to do his own research?

I don’t mean to put the author on the defensive and I certainly don’t want an explanation or answers to any of these questions. It just seems to me that when the parent is doing the homework, the kid is missing out on the learning.

And frankly, at 19 years old, the “kid” is old enough to be doing this for himself.

Maybe father and son need to have a good heart-to-heart chat about this? Look into their motivations? See who really wants this to happen?

Because even if the pair decide to move forward in this career, the son won’t get very far if he lacks the motivation or ability to study and learn for himself. This might not be rocket science, but there’s still a ton to know and learn.

Motivation

Motivation is a huge topic all its own.

Back in the mid 2000s, Silver State Helicopters was a quickly growing helicopter training organization. They’d choose a city and start advertising free seminars where you could learn to be a helicopter pilot and be paid $80,000 a year. On the day of the seminar, they’d pack an auditorium with pilot wannabes. On stage, they’d have shiny helicopters and pilots in cool-looking flight suits.

Silver State was selling two things:

- A cool, awe-inspiring job. After all, what guy wouldn’t want to be a helicopter pilot?

- A big annual paycheck. $80K a year is certainly enough money to live on — especially when you’re currently struggling on the weekly take-home pay of a part time job.

Of course, Silver State crashed and burned when the economy tanked and kids couldn’t get $70-$80K loans for their flight training. Because the entire organization was built like a Ponzi scheme with tomorrow’s new students paying today’s expenses, the company ran out of money. They closed their doors very suddenly, leaving hundreds of students only partway through the program with nothing to show for it except a huge loan. There are still young people out there trying to dig themselves out of the mess Silver State left them in. I covered Silver State’s impact on the industry in this blog post.

In the email message quoted above, the dad mentioned that he’d talked to the flight schools and CFIs. He didn’t mention what they’d told him. Were they selling Silver State’s dream, too? The glamor job? The big paycheck?

Is that what’s motivating them to explore this as a career?

I’ve said it before and I’ve said it again: if you want to be true to yourself and ensure happiness for the rest of your life, pursue a career doing something you love.

I love to write. After eight years on a career path I was “guided” into by family pressure, I broke out and became a writer. It took a while, but I found a lot of success and a lot of happiness in my work.

After I learned to fly, I realized that I loved to fly. In an effort to do it more often, I pursued flying as a career. Again, it took a while, but I found enough success and a lot of happiness in my work.

If you’re interested in a career as a helicopter pilot, is it because you love to fly? Or is it because you want to make your friends envious? Or pull in the big paychecks the flight schools claim are possible?

And if you haven’t even flown in a helicopter yet, what the hell are you waiting for? You might hate it. Take a demo lesson where you can manipulate the controls beside a CFI and even log the time. (Why not if you’re paying for it, right?) See if it’s right for you.

(This is yet another reason why you should not buy into a “program” with a flight school You might get 20 hours into your training and decide it’s just not right for you.)

And if you want to know what a career as a helicopter pilot is really like, talk to a helicopter pilot. No, not the owner of the flight school or the chief flight instructor there. And no, not a 400-hour CFI who’s paying his dues so he can start being a helicopter pilot elsewhere. I’m talking about real helicopter pilots — the guys and gals who have been doing this stuff for years. Someone who is serious about learning what it’s really like will talk to as many real pilots as he/she can.

And no, posting messages on helicopter pilot forums does not count. Don’t be lazy. Find real local pilots — EMS, ENG, agricultural services, fire suppression, heavy lift, tour, etc. — and talk to them face to face. They will talk to you. If you visit them at their base and they’re not busy, they’re likely to show off their helicopters, too. (Sure beats getting misled by wannabes who are using the Internet to hide their identities and lie about their experience.)

The Helicopter Job Market Today

As far as I can see, the market hasn’t changed that much. Yes, we no longer have the flood of low-time pilots pushed into the job market by Silver State. But we do have young veteran pilots released from the military. So there are still far more low and mid-time pilots than jobs for low and mid-time pilots.

What is “low time”? Anything less than 1,000 hours is widely considered low time. That’s the amount of pilot in command time that most pilots need to get a job as a real (non-CFI) pilot. You usually get that time as a CFI — that’s the normal career path.

Is it possible to get a pilot job with less time? Yes.

WIll it be a good job, one with real career potential and opportunities to learn and practice new skills? Maybe.

Will it pay well? No. (Hell, if they had a big payroll budget, they’d likely use it to obtain more experienced pilots that would keep their insurance costs down.)

Even when you’ve gotten all your certificates, you still need to compete with other brand new pilots to get the CFI job that’ll make it possible to build your first 1,000 hours. Once you get that job, you need to keep it until you have enough time to compete again with other 1,000-hour pilots for your first entry level pilot job. There are no guarantees. Employers — whether they’re flight schools or tour companies or offshore drilling transportation providers — will only choose the candidates they think are best for their organization. The whole time you’re learning and flying and working you need to set yourself apart from the others to prove that you’re the best.

Like many careers, as you work your way up the ladder, building valuable experience and proving over and over that you’ve got the right attitude to get the job done, opportunities will open themselves to you. The more experience you have, the more opportunities will be available. And yes, some of them will come with very nice paychecks.

I have friends in this industry who are constantly being contacted by employers interested in hiring them. One friend recently turned down an offer five times — even after he was offered a $10K signing bonus — and finally signed when they reached an agreement about the contract length, location, and conditions. Why do you think they were so anxious to have him at the controls of their Huey on that fire contract? He has a great reputation as a responsible, safe pilot who takes excellent care of the equipment and always gets the job done.

It would be nice to be in my friend’s shoes, wouldn’t it? But he didn’t get there by luck. He got there through hard work and the right attitude — for more than 20 years.

Being a successful helicopter pilot is not easy. It requires a lot of hard work. It often requires working in less than optimal conditions, doing things you might not want to do. It requires being willing to learn — and even master — new things. You have to have “the right stuff.”

What do you think?

I’m sure this blog post will be seen by plenty of pilots and maybe even some employers who have been in the industry at least five or ten years. What do you see as the current trends? What information can you add to this? Advice?

Please use the comments for this post to share what you know. My information is limited — you can help me round it out for other readers to get more value from what I’ve already said here.

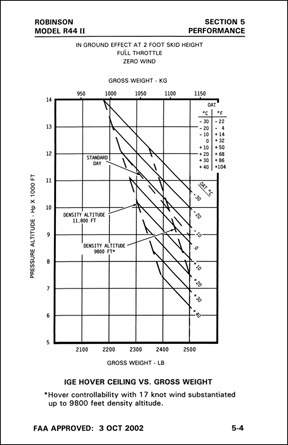

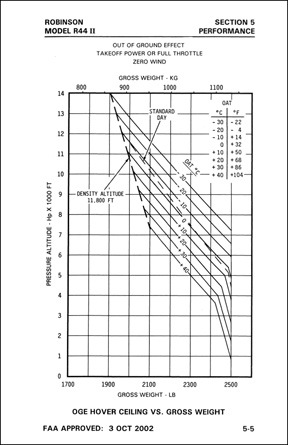

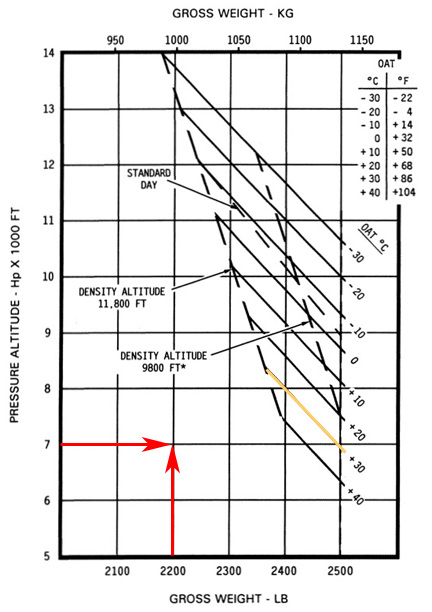

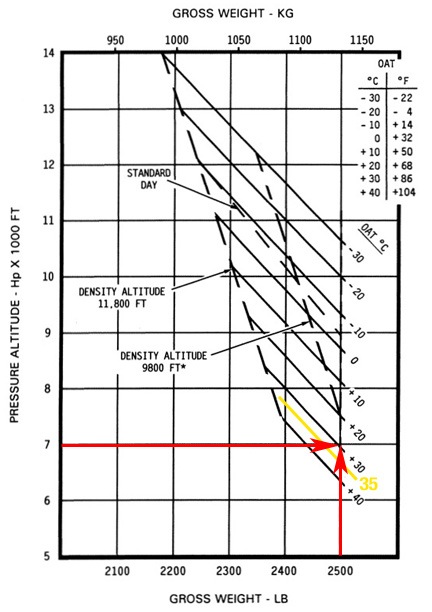

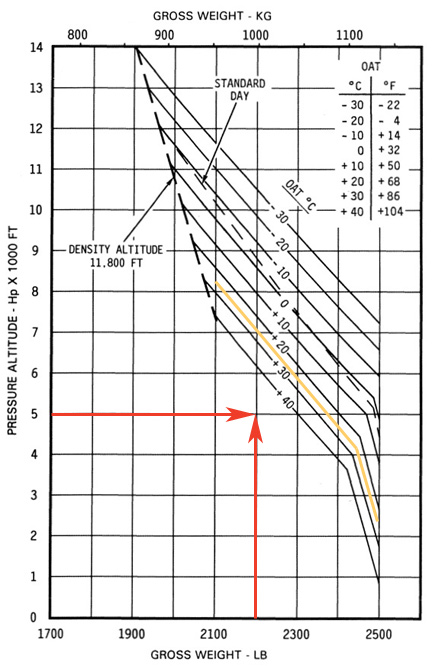

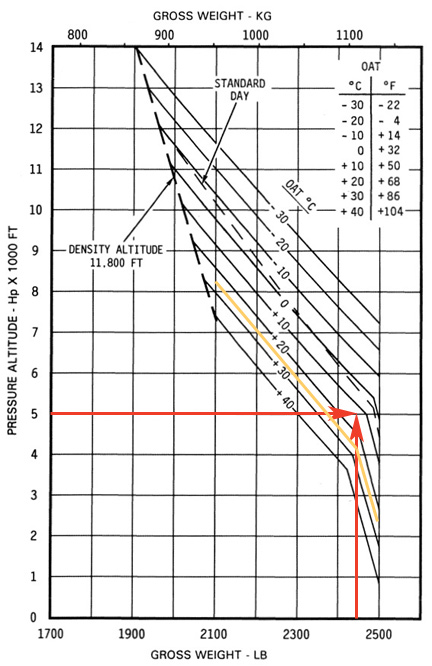

A look at the performance chart for an R44 (Raven I) makes it pretty clear why the pilot had trouble maintaining altitude at slow speed. At max gross weight on a 30°C day, the helicopter can’t even perform an out of ground effect (OGE) hover at sea level, let alone nearly 5,000 feet. That means it would have to continuously fly above ETL (approximately 25 knots airspeed) to stay in the air. At slow speed, a turn into a tailwind situation would rob the aircraft of airspeed, making it impossible (per the performance data, anyway) to stay airborne.

A look at the performance chart for an R44 (Raven I) makes it pretty clear why the pilot had trouble maintaining altitude at slow speed. At max gross weight on a 30°C day, the helicopter can’t even perform an out of ground effect (OGE) hover at sea level, let alone nearly 5,000 feet. That means it would have to continuously fly above ETL (approximately 25 knots airspeed) to stay in the air. At slow speed, a turn into a tailwind situation would rob the aircraft of airspeed, making it impossible (per the performance data, anyway) to stay airborne.