Nine weeks was enough.

On Saturday, we left Wenatchee. I’d been in the area — Quincy and Wenatchee, WA — since June 8 and was really ready to go. But there were a few things that needed doing before we could go.

A Day in Seattle

First I had to meet up with my husband. He’ll be joining me for our return drive to the Phoenix area. He flew up from Phoenix to Seattle on Alaska Airlines with some luggage, his bicycle, and Alex the Dog. His flight was scheduled to arrive at 9:30 AM Thursday, so at 6 AM that morning, I was in the truck, driving west to meet him. We had a nice reunion at baggage claim carousel 14, where Jack was very surprised to see me waiting for him when they rolled in his new travel crate.

SR-71 on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, WA.

Not to waste a day in Seattle, we had breakfast at 13 Coins near the airport and then headed over to Boeing Field for a visit to the Museum of Flight. We spent a few hours there, enjoying the exhibits. It’s a great aviation museum with something of interest to people of all ages.

Afterward, we went to Mike’s cousin’s house in the northern part of Seattle, not far from the University of Washington. Mike’s cousin Rick and his friend Lisa live in a tall, narrow house on a quiet residential street. We went for dinner at a nearby Italian restaurant, where were were joined by my friend, Tom, who I hadn’t seen in about 15 years. Tom, who lives in Vermont, was in the Seattle area on business and we managed to plan our day in Seattle for the same day Tom had some free time. It was great to see him.

Afterwards, we drove back to Wenatchee along scenic Route 2. Unfortunately, we left too late in the day to see anything; it was dark long before we reached the pass. It was also a bit foggy. I’d love to drive this route on a nice day. I flew it in June with my Twitter friend, @Jodene, and it was incredible.

Moving the Helicopter

The idea was to fly the helicopter back that way the next day. I’d booked tickets for Mike and me on Horizon from Seattle to Wenatchee on Friday’s 4 PM flight. The plan was to spend Friday morning moving the trailer from where it was parked in a Wenatchee Heights orchard back down to Wenatchee, where we’d get one of its tires replaced. Then we’d fly the helicopter to Boeing Field, where one of my mechanics is based. Then we’d catch that 4 PM flight back to Wenatchee, finish packing up, and be out of the area by Saturday morning.

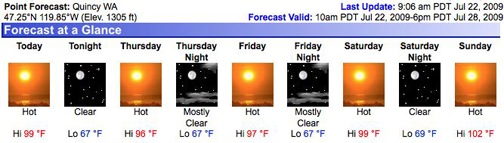

The weather didn’t cooperate. It had been almost rain-free all summer, but it poured like hell on Friday in Wenatchee. The storm came from the north and moved slowly to the southeast. We managed to stay on schedule to fetch the trailer and get its tire changed, but when we were ready to take the helicopter to Seattle, a thick blanket of clouds clogged both mountain passes — Snoqualmie (I-90) and Stevens (Route 2). There would be no flight that day.

It was unfortunate because, as Seinfeld’s Kramer might say: in my mind, I was already gone.

The next day, I was awake at 6 AM. It was a beautiful, clear, sunny morning. If we could get our act together quickly, we could fly to Seattle and catch the 9:55 flight back to Wenatchee. Otherwise, we’d have to wait until 4 PM. After checking the weather as well as I could, I decided to go for it.

We were airborne by 7 AM. I climbed out with a direct-to Cle Elum on my GPS, requiring a 500-800 fpm climb rate for the first 5 minutes of the flight to clear the mountains. As we climbed, we could see the tops of clouds out in the mountains in the distance ahead of us. I was hoping that those cloud tops were for a shallow band of clouds and that there would be room beneath them for us to fly over the highway through Snoqualmie Pass.

We descended over Cle Elem and hooked up with I-90. Soon we were flying under the cloud bank with plenty of space between us and both the ground and the clouds. But as the terrain rose toward the pass, the clouds descended. We passed Easton and things began to get uncertain. Just short of the pass, we realized that the clouds came right down to the ground. There was no safe way through.

I turned around and headed back toward the edge of the cloud bank. There were plenty of tempting holes in the clouds where I could have passed through to fly above them. But I don’t like flying atop a bank of clouds. Eventually, you have to come back down, and if there’s no hole on the other end, you’re stuck up there. I did not want to put myself into that situation.

Mike took this shot as we approached Mt. Rainier. You can see a little bit of the cloud cover around its base.

We reached the edge of the cloud bank and turned to the south. We climbed and were soon above the level of the clouds. Mt. Rainier was poking out of the top of the cloud bank, but there was plenty of clear, cloud-free space around its base. We headed that way. Beneath us, several deep valleys were full of cottony clouds, as if stuffed by some well-meaning giant. Ahead of us, Mt. Rainier rose tall and proud and snow-covered out of the rocky terrain. Grassy slopes of its foothhills glowed bright green with thick grass, speckled with tall pines and granite outcroppings. The views were incredible.

Unfortunately, I was too concerned with our flight path to enjoy the view. I needed to get under the clouds in a valley that sloped downward toward Seattle. I needed to do that without actually flying through any clouds. My first instinct was to find a road, since most roads lead to a pass. But some roads climb, descend, and climb again. Any of the climbs could take the road into the clouds. I soon realized that a mountain stream or river would be better.

We found just the one we needed on the northwest side of Rainier. I descended at 2,000 fpm at the edge of the cloud bank, ducking under it with plenty of room to spare over the riverbed. We followed it closely, winding back and forth, keeping an eye out for wires. Finally, the canyon opened up and we could see homes and towns in front of us. A while later, the skyline came into view on a typically gloomy Seattle day. We touched down at Boeing Field at about 8:45 AM. We’d logged 1.6 hours of Hobbs time on a flight that should have taken 45 minutes.

You can see our entire flight path on the chart here:

But the bigger miracle was that we caught a cab to SeaTac and were sitting on the Wenatchee-bound plane less than an hour later. By 10:30 AM, we were on the ground in Wenatchee.

By 3 PM, we were packed up and on the road, headed for Walla Walla. But that’s another part of the story.

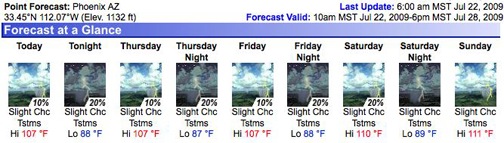

I thought about this as I made my coffee and fired up my computer to check the weather. I also thought about the other ways the drying flight could play out — ways that were better for all concerned.

I thought about this as I made my coffee and fired up my computer to check the weather. I also thought about the other ways the drying flight could play out — ways that were better for all concerned.